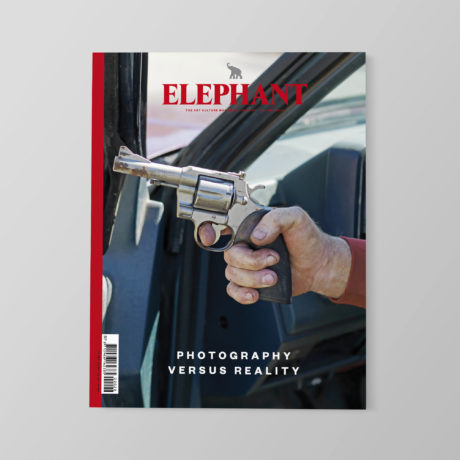

The camera, as Susan Sontag pointed out, is often deployed as a means of coping with angst. The most common photographic impulse is to seek comfort in familiarity and sameness, as is evident in the dominant aesthetic tendencies of photographs on Instagram and Pinterest, where the world is clean, tidy and “just so”.

The prevalence of photographic perfection, assisted by the development of easy-to-use editing technologies, however, has a side effect: even normality doesn’t look real anymore.

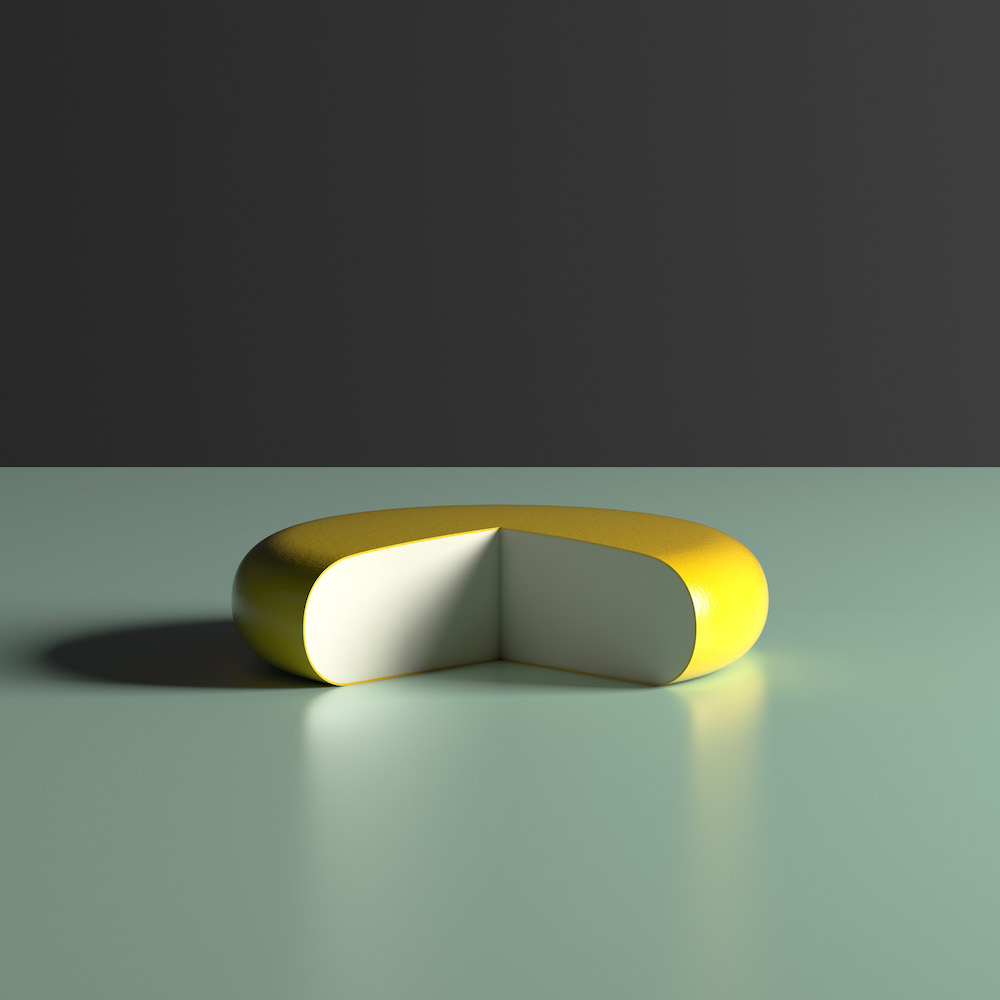

“In terms of photography I think I’ve always been interested in a space beyond ‘reality’, the space most commonly occupied by advertising and mainstream film,” says Manchester-based artist Pat Flynn. “The visual language they both use possesses a kind of immortality, an unashamed seduction.” Each of Flynn’s photographs draws on miracles, myths and folklore, stories embedded in visual pop culture, with the purpose of elucidating reality. In order to show us something about the latter, Flynn puts photography’s fraudulence to use, creating pointedly attractive and empty digital photographs of objects made with 3d computer graphics software. “Rendered photography offers the artist the opportunity of constructing photographs that are at once real yet entirely fetishized.” Flynn’s critique shifts towards the way we look at images, questioning the trust we put in them—looking for the real in something that can never yield it.

Flynn began his practice as an artist in the neoliberal ’90s, after the frenzied consumerism and conservatism of the West in the 1980s. Some 11,426 miles away, in a New Zealand suburb, Yvonne Todd was also starting out as a photographer in the post-Pictures Generation era, inspired by the flatness of commercial photography and the fetishistic nature of the medium. The main body of her work focuses on the construction of female characters in everyday culture: deeply disturbing portraits of cosmetics counter employees, frazzled starlets, afflicted housewives, anorexics, frumpy Christians. Yet her lesser-known photographs of inanimate sundries—fluffy sweaters, hardware, asthma inhalers or a wholesome glass of milk—are even more terrifying. Like Flynn, she emphasizes the uncanny nature of the photograph, the paradox of blindly believing in what you see. Truth is far weirder than fiction. As John Baldessari has said: “For most of us photography stands for the truth. But a good artist can make a harder truth by manipulating forms.”

“Photography confuses us because it looks real, but it does not exist outside the image”

Though many photographers in our times mix different techniques and sensibilities, photography still persists as representation of truth and reality in the news. Using the vocabulary of photojournalism, Philippe Chancel’s Datazone project deals with news as art and art as news, travelling to areas that are rarely explored in genuine depth, to question the way we see and what we’re used to seeing. Dissatisfied with the visual storytelling in the mainstream media, Chancel deals with the tension between the visible and the invisible, who and what is seen and unseen. Often, a photograph indicates not what is there, but what isn’t. “I see North Korea as a huge open-air museum; I witness the reality of architectural follies in the Emirates; in Fukushima, Japan, I see that the magnitude of natural disaster exceeds the most dramatic feature films. In ‘murder city’, Flint, the United States, I plunge into a nightmare straight out of a B movie. I lean towards recurrent events that are virtually unknown in the usual media channels.” Inspired by William Burroughs’s novel Interzone and the fragmentary writing technique he conceived of as a way to transgress the boundaries of the unexplored, Chancel’s own work asks: “Fact or fiction? Borders are porous, are reversed or completely disappear. My experiments with the real are a way to precipitate often conflicting issues of the day—the cynicism of powers, ecological devastation, the spectacularization of capitalism. Between visible and invisible, hidden and revealed, truth and lies. I don’t want to believe my eyes.”

Hanging on the walls of the Elam School of Fine Art in Auckland last year was Kate van der Drift’s The Oasis and the Mirage. The series focuses on landscapes altered by colonization, industrialization and the weather, “linking landscape’s reality with that imagined by its conceiver”. Photography is often endowed with a sense of the real, whether that is the photographer’s intention or not, because it usually deals only with the past—it seems to offer proof that something has, at some time, been there, in front of the camera. Van der Drift’s process begins in reality, photographing landscapes, but it ends in conjecture: we are faced with a reality that is contained exclusively in the photograph. At her studio, she prints the landscape photographs and works on them by hand with paint. Uploading them again to the computer, she then manipulates them further using digital software. “I wanted to create images of scenes that could be ‘real’ from the past, present or future,” she explains. “This was important to me because I was asking the viewer to look at the altered landscape and decipher whether it was manipulated by me or through human or natural interactions with the surface of the land.” Van der Drift represents the new role of the photographer, who does not (cannot) claim the photograph as a representation of reality or truth, but who can visualize another space, far less certain. “Photography does not depict truth. It is with this critical eye, practised at mistrusting photographs, that the view of the landscape is questioned.”

Photography confuses us because it looks real, but it does not exist outside the image. This is what photography has always done. When I look at family albums from the 1960s the photographs in them give me the impression that everything in the past had a fuzzy, dreamy, warm colour, that the actual light was different then. I was born in the ’80s, but I’ve checked with people who were around then and they say it didn’t really look like that. The identity of the past has been shaped by photographs. Now, the identity of the present is constantly edited, so that we’re aware that photographs represent a far looser, more abstract truth. Contemporary photographers are consciously embracing the possibility of a dimension that only exists in photography. As Christian Metz writes in his essay “Photography & Fetish”: “myths are always true, even if indirectly and by hidden ways, for the good reason that they are invented by the natives themselves, searching for a parable of their own fate.”

“Now, the identity of the present is constantly edited, so that we’re aware that photographs represent a far looser, more abstract truth”

Exploiting the space between the real and the unreal that is contained in the medium of photography is a constantly evolving area for photographers, since manipulations can be so sophisticated that it’s impossible to tell the difference between nature and artifice. Today’s photographic dimension is a hybrid that makes the traditional binary of real/unreal redundant. What does “real” even mean, anymore? London-based artist Antonio Marguet writes: “When I first stumbled upon the thought that ‘nature is alien to me’, I started to engage in our new ecology and synthetic environments, leading to a process of distancing from ‘mother nature’. I began thinking about how this same displacement allows a gap for mystical qualities to be transferred to this inanimate nature, turning it into a fetish. My interests rely on this transportation of magical components beyond their physical reality.” At his most recent solo show in spring 2016, at Fotogalleri Vasli Souza, Malmö, Sweden, he presented some of the works that illustrate this assimilation of opposites. Marguet, who is also a sculptor, is fascinated with plasticity—his father ran a bubblegum factory—and with the ability to “sculpt” reality through photographs, either building by hand, or by moulding digital data on a computer.

Taking the medium as far as it can go from any sense of the real—to rupture the limits of the temporal and the spatial as we know them—involves finding a language that belongs only to photography. More concerned with the materiality of the photograph than the sociopolitical implications of the medium’s relationship to truth, Barbara Kasten—inspired in turn by the ambitions of Bauhaus photographer and thinker László Moholy-Nagy—has been experimenting with abstract photography for 50 years. She constructs room-sized sets that she then photographs, removing from them any kind of representational object. Her pioneering practice, showing this year in a retrospective that has toured from the ICA in Philadelphia to MoCA in Los Angeles, is attempting to redefine the medium as something not centred on the human stance.

Philippe Chancel, Earthquake Haiti, 2011. From the Datazone project. Courtesy Mélani e Rio Gallery

Her ideas have filtered back to England. Felicity Hammond—winner of the British Journal of Photography’s International Photography Award 2016—is doing exciting work to comment on the role of the photograph, by extracting photography from photographs. Using photography as her material rather than her medium, Hammond enquires into different forms of social and cultural construction in the image world. Her process turns constructed images back on themselves: she photographs Photoshopped images, deliberately selected from various types of imagery related to urban regeneration (digital architectural renderings, blueprints, real-estate developers’ billboards and brochures for luxury apartments). Then, she manipulates the photographs again, stretching the data using CGI and other advanced photo technologies, finally printing the images onto bendable acrylic sheets that can be fashioned into sculptural photo-objects. The result is a physical object, made out of digital data, both solid and simulated.

How does all this work that’s being done relate to the times in which we are living? What is, as Metz called it, the parable of our fate? We have more visual information than ever before, yet our reality is full of hidden uncertainty. Perhaps the defining anxiety in 2016—the things we cannot see—helps explain how photography has shifted in order to cope with the impossibility of seeing.

Perhaps Roland Barthes put it best: “Ultimately—or at the limit—in order to see a photograph well, it is best to look away or close your eyes.”

This feature originally appeared in issue 28

BUY NOW