A woman sits astride a huge motorbike, surrounded by trees. Her hair is white and her cheeks hollow, but she is anything but frail as she poses nonchalantly, leather-clad, hand on hip, gazing defiantly out from beneath an androgynous fringe.

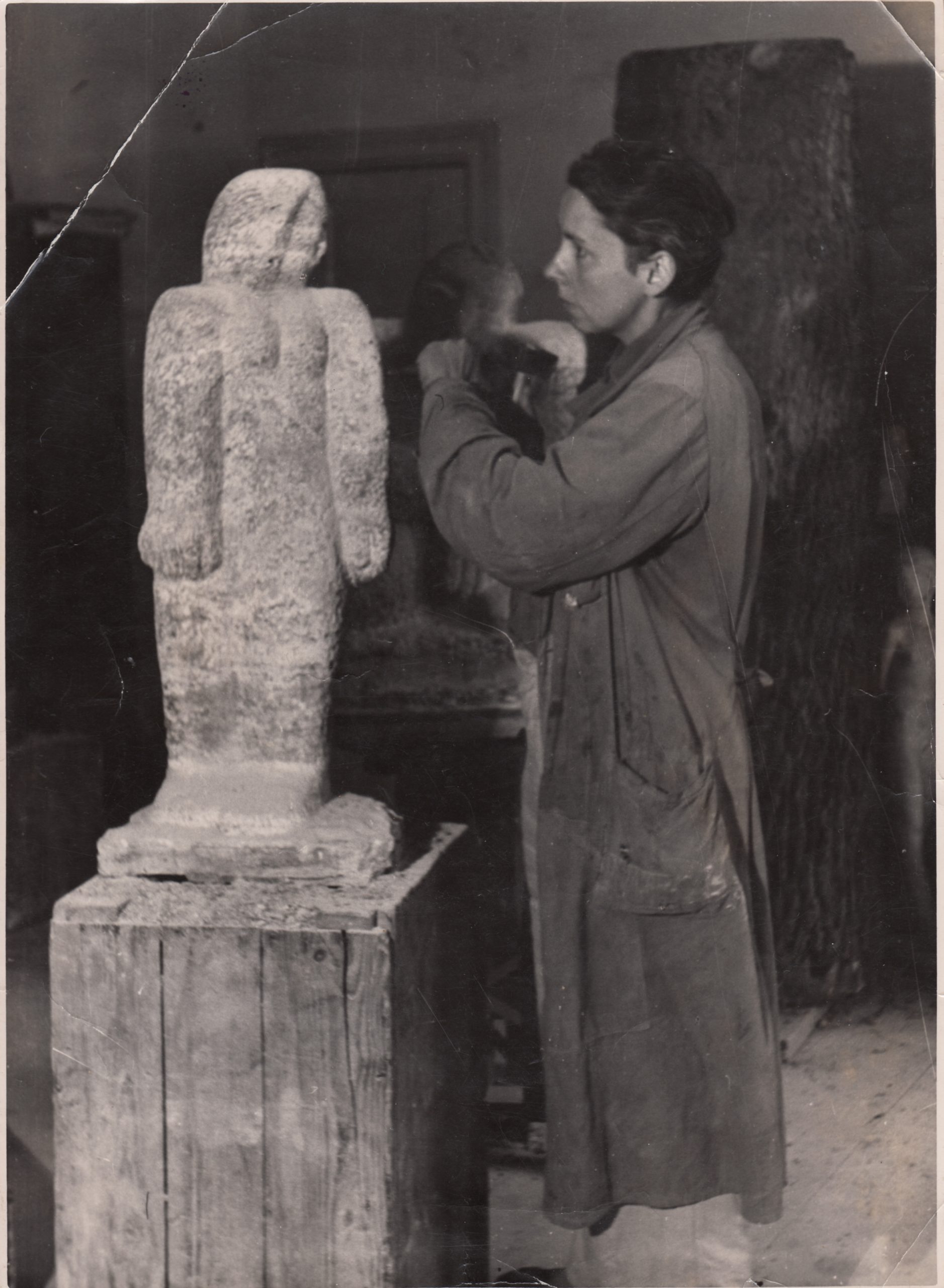

It’s a tantalising introduction to an artist. Stefan Moses’ Portrait of Louise Stomps (1982) captures the German sculptor in the final chapter of a long life, straddling her beloved Yamaha in the woods near her remote Bavarian home. Stomps had spent her first 60 years in Berlin, living and working through Germany’s most turbulent period. She began sculpting during the Weimar years and found her voice amid dictatorship and war. Her haunting pieces, wrought from wood and stone, earned her recognition, but by the time she died aged 88 in a motorcycle crash, Stomps was very much an outsider.

Moses’ photograph is displayed as part of Louise Stomps: Figuring Nature, a retrospective at the Berlinische Galerie. Guest curated by the Verborgene Museum (Hidden Museum), an organisation dedicated to reappraising female artists, the exhibition makes a compelling case for reinserting Stomps into the story of European art, with curators Marion Beckers and Elisabeth Moortgat describing her as “one of the most important sculptors of the 20th century”.

The exhibition brings together 90 pieces spanning seven decades. Stomps began sculpting in the 1920s but she was only able to dedicate herself to her practice after her 1927 divorce. As a largely self-taught artist, single mother and queer woman, Stomps was never going to slot easily into the male-dominated establishment. Nevertheless, she did have predecessors and peers.

“Stomps remained in Germany but resisted the regime, distributing anti-Nazi pamphlets and sheltering a communist in her home”

Just as Stomps was finding her medium, a group of female sculptors were offering refreshing perspectives on the medium. Some of these artists are still remembered today (such as Käthe Kollwitz and Renée Sintenis) but most have faded from view. It has taken concerted efforts by resourceful curators

to piece together the legacies of artists such as Tina Haim-Wentscher and Sophie Wolff, whose stories have been obscured by dismissive critics, wartime destruction and an exclusionary canon.

Stomps was from a generation after these artists, but she moved in overlapping circles and would have been aware of their work. She studied under avant-garde pioneer Milly Steger and was in a relationship with sculptor Lidy von Lüttwitz. Stomps exhibited fairly regularly, but in 1936, she stopped out of solidarity after the authorities removed “degenerate” work by peers (including Kollwitz) from the Berlin Academy of Arts. Unlike the many artists who fled to exile, Stomps remained in Germany throughout the war but resisted the regime, distributing anti-Nazi pamphlets and sheltering a communist in her home.

“Using wood from the nearby forests, Stomps drew on organic shapes in an attempt to capture, “the soul” of the natural world”

Stomps’ changing style charts these social and political upheavals. Her early figurative work brims with flowing lines, generous curves and erotic possibility. Shimmering slabs of marble or wood are coaxed into smooth curves, depicting tenderly entwined couples or elegant female nudes. By the end of the war, however, any residual Weimar sensuality had been swept away by devastation and loss. Pieces such as Trauer (Grief, 1947), Gemeinsame Klage (Shared Lament, 1949) and Hiroshima (1960) reveal an artist grappling with trauma. Now her figures crouch or lie in foetal position, while her couples pull away from one another, estranged. Stomps also moved deeper into abstraction. Ruhende (Recumbent Figure, 1955-56) presents a headless arc of flesh, while In Bewegung (On the Move, 1953) approximates a torso, an amputee cut off at the arms and legs but still somehow ploughing onwards.

In the early 1950s, Stomps enjoyed a period of relative renown. She co-founded the Professional Association of Visual Artists in Berlin, was shortlisted for several high-profile commissions and won the Berlin Art Prize. However, this recognition was short lived. “In 1945, a time of new beginnings…she was right in the middle of it and she was an important person” says Beckers. “But then, in the course of the 1950s, this slipped back again. Female artists were pushed back, and it took until the 1980s for women to come to the fore again.”

“As a largely self-taught artist, single mother and queer woman, Stomps was never going to slot easily into the male-dominated establishment”

In 1960, Stomps left Berlin for rural Bavaria where she converted an old watermill into studio. She would spend the rest of her life there in seclusion, driving her sidecar to occasional exhibitions, but generally ignoring the art world. She never stopped working, however, and the move signalled the beginning of a new phase.

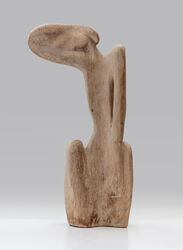

Predominately using wood sourced from the nearby forests, Stomps now drew on organic shapes such as tree stumps, clouds and rock formations in an attempt to capture, “the soul” of the natural world. Despite the change of subject, a sense of darkness and decay lingers in these pieces, detectable in the yearning fronds of Vegetativ (Vegetative, 1965) or in the burnt-looking desiccated Schatten (Shadow, 1972).

“The exhibition makes a compelling case for reinserting Stomps into the story of European art”

Stomps obsession with the human form also continued. Standing sentinel in the Berlinische’s stairwell are tree of her most arresting works: Einsamer (Solitary One, 1962), Gilgamesch (Gilgamesh, 1980) and Pilger (Pilgrim,

1986). Each stands several meters tall, offering variations on the same impossibly slender figure, who looms above our heads gazing mournfully outwards.

Figuring Nature ends with a short film which offers a glimpse of Stomps the woman. Made for Bavarian television shortly before her death, the footage shows Stomps in her cluttered studio, surrounded by cats, woodworm and half-finished sculptures. Like Louise Bourgeois or Maggi Hambling, part of Stomps’ appeal lies in her iconoclastic rejection of expectation about how an older woman should behave. Here the artist more than delivers, standing surly and hunched before the camera, brow furrowed as she chisels away at a new piece.

This work will eventually be named Der Aussteiger (The Outsider, 1988). It’s an appropriate title for one of the last pieces by an artist who removed herself from the art world. Yet, for Stomps this never felt to her like much of a sacrifice. “For me, my work was always something I was happy to give everything up for,” she says in the film. “You don’t do these things just for yourself … you [try to] emanate something to others, don’t you?”

She pauses for a moment, apparently content, just before the camera cuts to black. “That’s reason enough, isn’t it?”

Rachel Pronger is a curator, writer and producer based in Yorkshire and Berlin. She is co-founder of the Invisible Women Archives

Louise Stomps, Figuring Nature: Sculptures 1928–1988

Berlinische Galerie, until 17 January 2022

VISIT WEBSITE