Hannah Hutchings-Georgiou traces the currents of care, rest, and radical compassion – multivalent and embodied acts of resistance and recovery – in Alberta Whittle’s practice.

My preparation for interviewing the formidable artist Alberta Whittle fittingly occurred inside a hospital. I was in an isolation unit, cordoned off from the rest of the ward, branded dangerous because of a small pill I was forced to swallow. The pill in question, which resembled an aspirin, was radioactive, tailored to my weight and measurements, and designed to destroy cancer cells that had threaded their way into organ and lymph and nerve. A day into my isolation, I began watching Whittle’s films on my phone, squinting at the cling-film-wrapped screen (suddenly I had become a hazard to everything), cradling the poetic bodies that danced and writhed and jutted and sung their way across it. Struggling with sickness, I tried to inhale then exhale to the rhythm of Whittle’s narratives, to her auto-narrated voice calmly repeating a breathing exercise, marking each filmic moment to the beat of her own heart. Traffic from Euston Road, thirteen floors below me, became a rolling wave in the background to her tranquilising tones, to the reviving rituals and near-religious choreographies her films portrayed.

To find out later, then, that around this time, Whittle, too, had been hospitalised and, like me, undergone surgery – and the invasive stress and trauma common to such treatment and settings of institutionalised care – felt more than coincidental. To know that I had found calm and connection, healing and balm from work dedicated to recognition, recovery and healing at the very time its author was encountering this process herself, was poignant. Our conversation started with this, and I am anchoring it in the revolution for recovery and revitalisation that Whittle’s artwork and practise so strikingly stands and calls for in the midst of our, her, and almost certainly the world’s ill-health.

Alberta Whittle looks incandescent and sounds jubilant on my laptop screen, despite the health issues that have dogged her during the summer of 2024. There is, of course, much to be jubilant about: Whittle was recently awarded her PhD from Edinburgh College of Art and opened a powerful site-specific show at Mount Stuart. She has also been busy preparing for multiple exhibitions at Stephen Friedman (a group show) and Nicola Vassell (a solo one); and yet, she is still thinking of new projects, new collaborations, new modes and methods with which to consider how trauma is processed in the body. “I’m getting ready to birth something new”, she reveals, “a film about the body and health, and how to bring in the language or aesthetics of poetry from my former work and research to this issue.” I’m impressed, not only by her industry and dedication but by her desire to use personal trauma to highlight that experienced by others. “We’re approaching winter, Covid is making a comeback, the spectre of Monkey Pox has returned – it’s amazing any of us are still standing given what’s happening in the world – but I want to ask what makes particular bodies more vulnerable than others.” It is not a new question when it comes to Whittle’s work, but it remains one of resounding relevance. In fact, this point of consideration echoes throughout her entire interdisciplinary repertoire to date. Care and compassion for the most vulnerable, the most marginalised identities, bodies and communities, are central to her artistic practise. That a new film about this is gestating, partly in response to her own experiences of vulnerability and trauma, recovery and healing, demonstrates the radical kindness, as well as resistance, that motivates Whittle as an artist.

Situating work in care when representing trauma is, in itself, a kind of healing. So many of Whittle’s films are rooted in this rich and nourishing empathy and kindness that moves from the self to the general, from the individual body to the communal one. Sitting in the isolation room, removed from all forms of human contact, I watched works like RESET (2020) on repeat, and despite it mirroring my own predicament of confinement and state of solitariness – not to mention sickness – Whittle’s film encouraged me to commune with myself in this place, and gently drew me into its shared sense of kinship and communal connectivity. Made during the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic and the international resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement after the murder of George Floyd, RESET weaves fears about global contagion, xenophobia, racism and its gothic imagistic antecedents into the theories of Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick and the poetry of Ama Josephine Budge.

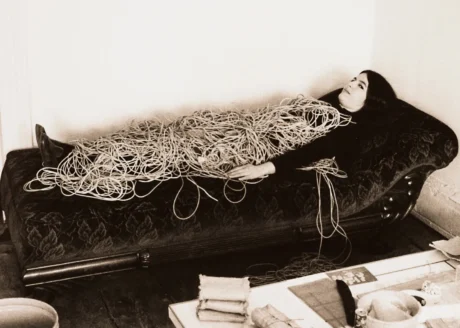

As its title suggests, RESET takes its point of resumption and renewal from the position of loneliness and the place of isolation which the pandemic notably opened up. Holding within its split frames the pained juxtaposition of change and stasis, beginnings and endings, individual solitariness and universal togetherness in this separation, RESET creates space for conflicting emotions to be felt and heterogeneous happenings to occur; for care and hurt, healing and grief to coexist. Thus we see a murmuration of starlings dive against a sun-strewn sky as well as crowds of masked individuals protest state brutality towards Black and brown bodies the world over. We see a young woman clad in a lattice of macramé drapes awaken in an empty room as well as a snake stealthily swim through a swamp, slowly advancing on its prey. We see dances of empathy for the past and snake-like sapience surge towards the future. We see the promise of new dawns as well as the punch of police violence.

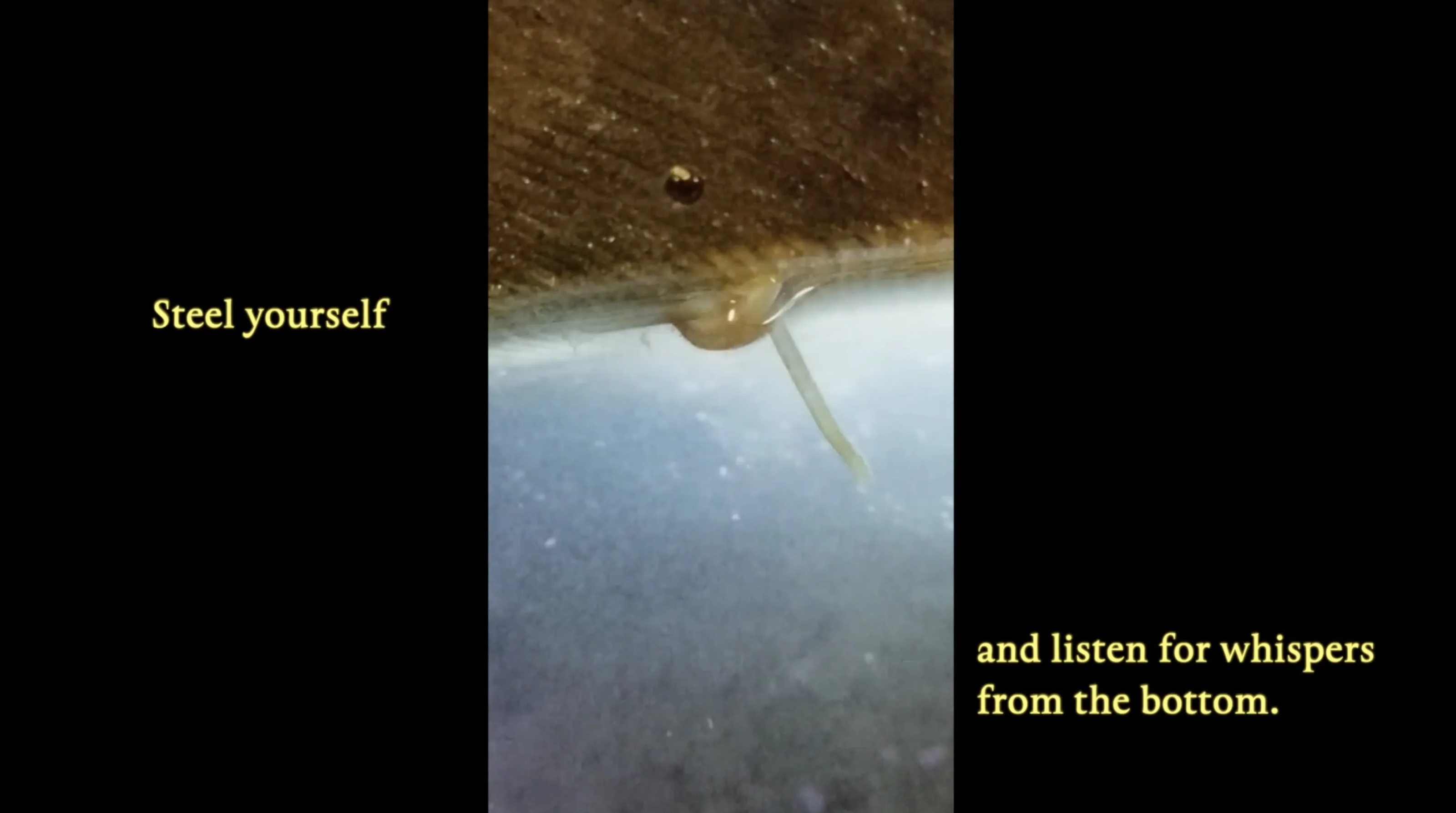

Like several of Whittle’s subsequent short films, RESET teaches us to breathe in the midst of suffocating circumstances. At a time when fresh air was both rare and rarefied, when an airborne virus had the potential to drown the human respiratory system and when white supremacist state brutality was literally choking its Black victims, Whittle reminded us calmly and courageously, hopefully and defiantly, to breathe again. “I’m trying to learn how to heal,” she says close to the camera, as footage of the snake and photography of Black ancestors close in around her. “Take a deep breath,” she instructs with an equanimity all of her own, as her face is replaced by microscopic imagery of an almost kaleidoscopic and molecular configuration. Breathing here becomes centred in Whittle’s own breath, concentric in the abstracted images the lens hypnotically and slowly encircles.

Moving through vital and sacral areas of the body, Whittle ‘resets’ our neurological as well as psychological sense of self, but also the relationship between film and viewer, absent participant and present narrator, the digitally depicted world and the material body. Breathing in this instant is boundary breaking, simultaneously defying restrictions and unifying all in the face of global illness and isolation. Resetting ourselves emotionally and physiologically, we begin to see the work – and the world – anew. As is the case with her later films, A Black footprint is a beautiful thing (2021) and Lagareh – The Last Born (2022), the instructions and breathing exercises in RESET become an anticipatory tool for grief, as well as a ritual to aid healing and recovery. The basic essence of living is, in this context, essentially, radically life-saving and life-affirming.

RESET carefully holds the viewer in the trouble as much as it asks you to behold it. Part of this act of care, as Whittle discusses with me, is acknowledging as well as facilitating the ongoing process of recovery. In Whittle’s work, recovery is as much about recovering a sense of who and what you are in the face of trauma as it is about healing from the experience itself. It is about recuperation of the past in addition to the means and methods of recuperating from it. Recently, the concept of recovery has struck a deeper, more personal note for the artist and her work: “My experience in hospital made me think about what recovery looks like. I made a small post about it on Instagram because I think we’re all recovering from something – whether it is a medical disaster or just how poorly we’re treated in the world. We’re all in a space of recovery. That is really where I’m going to in this work. I want to make space for myself and audience members to dig deeper in terms of really thinking about what they need for their personal recovery. And I want us to really give ourselves permission to recover. When I was unwell, I had to give myself permission not to labour.”

Quite often in Whittle’s work, recovery moves from the physiological and psychological to the socio-political and the archaeological. In A Black footprint is a beautiful thing (2021), those same breathing exercises – this time addressed to herself (‘I must remember to keep breathing…’) – are used to recover memories, ancestral realities, actual spaces of refuge, positions of power and pride, as well as fragility, fear and failure: all traces, however faint or bloody, of the past. Recovery in the film begins with Whittle’s walk along the Barbadian shore, the country of her birth, perhaps retracing the impressions in the sand her ancestors made centuries ago. Recovery is also the stony foundations of a fortification overlooking the beach, and the remnants of colonial and Eurocentric representations, however painful, of her Afro-Caribbean forebears. It is the hemp rope which binds the hands and the heavy plaster of prejudice upon which former eugenicist and colonialist theorists heaped on Black individuals – and in which Whittle memorably coats her face. Retracing this, remembering it on her own terms and in her own time, recovery occurs, but not without the aching acknowledgment that old trauma echoes in new forms today. Splicing the screen, Whittle juxtaposes footage of recent EDL aggression with her own slow immersion into plastered whiteness. In doing so, she emphasises the connection between white hostility and Black erasure, between socio-political and colonial oppression and the erosion of Black presence and power. And yet, by slowly removing flakes of plaster from herself and harmoniously humming to shots of glistening sea vistas and underwater shipworms, Whittle regains composure and recomposes herself through scenes of slow but persistent resistance. After reflecting on the historical injustice that exists in current systems, recovery becomes faith in the ecological, in the non-hierarchical, in the pre-colonial, in the creative collective that assists in the making of this film – a permanent Black footprint in and of itself.

From breathing techniques to humming, singing and dancing, the vocalisation and physicalisation of recovery is repeated across Whittle’s films. In Between a whisper and a cry, an exploration of meteorological and environmental catastrophe and its connections to colonial exploitation is enacted out in the dancing of a young Black woman. Fluidly gesticulating and isolating her limbs, the dancer rebelliously reclaims and re-establishes her authority in a wood-panelled room decorated in maritime memorabilia and insignia. Not only does the dance create a storm in this formal civic space but signifies that one is literally on the horizon, as we later see when satellite imagery foretells of cyclones to come. Satirically dressed in a sailor’s outfit – a gesture to the power swap of who now weathers and masters the seas – the young woman reformulates recovery into a dance of disruption and retribution, a ludic return of repressed power involving bodies, land and sea. Dance in Between a whisper and a cry, as it is in her Venice Biennale film Lagareh, frames recovery as a ritualistic exercise of release for the individual, as well as a practise between Black diasporic and Atlantic communities and the oppressive colonial forces from which they literally continue to shake free.

Recovery then doesn’t preclude the complex emotions necessary to break free. In fact, as Whittle observes to me, these films often come from “very deep emotional places.” Choreographies, gestures and formations are used to tap into deep-rooted feelings and deep-seated trauma, gradually allowing for understanding, transformation and liberation to spring up. “So often with the films,” Whittle explains, “they’re coming from a rage-filled place. I’m usually furious or sad when I start making them. But each work allows me to physically process something in its gestation and production. They’re made in a very bodily way. Fannie Sosa, who is an afro-sudaka dancer, artist, activist and researcher, writes about movement and this idea of how moving your body in a particular way can help you release and process certain pent-up emotions. This history of movement and dance, which I’ve practised in my life too, enables the audience of my films to feel. That there are these vibrations, whether it’s uncracking something in your body – I sometimes feel like my body is made of stone and I need to crack it in order for a different energy to appear or for a new layer to unpeel – or in nature, movement allows one to process these emotions. The films are very much like a sequential complaint – as Sara Ahmed discusses in her book of the same name – and they build onto one another, allowing the audiences to have access to these emotions and a space in which to connect with them.”

Like with Whittle’s inclusion of deep breathing techniques and dancing, actual space to recover these emotions (and from them) comes in multiple forms. For Lagareh, custom-made seating was installed as an extension of the language and grammar of the film. Complaint on screen for those lost to police barbarity (expressed through commemorative song, movement, and Whittle’s own compelling narration recalling the names of these men and women) turns into places of plaint off-screen, where designated areas in which to listen and absorb, feel and cry, are provided. In recent work, however, space for recovery has been literalised, with audiences encouraged to physically participate with and inhabit the work. Whittle’s site-specific exhibition at Mount Stuart, evocatively titled Under the skin of the ocean, the thing urges us up wild (2024), explores the wild and cultivated history of Bute, an island off the coast of Western Scotland. A culmination of two years of research at Mount Stuart and across Bute, as well as conversations with fellow artist and collaborator Sekai Machache, Under the skin brings together many of the themes and theories that flow throughout Whittle’s films, paintings and textiles. Metaphorical spaces in these works – the space created by poetry and narration, dance and symbolic depictions alluding to the Barbadian littoral – are displaced in those of Bute and its ancient geological, geographical, architectural and archaeological sites and sights. Interacting with and incorporating assemblages, paintings and sculptures, as well as her own reconstruction and reanimation of ancient Viking structures into its environment of ancient standing stones, burial chambers, ruins, house, and observatory, Whittle recreates Bute in her own colours. She renders it a poetic and poignant place in which to question and reflect on the histories of migration and fugitivity, communal control and order, land ownership and law, as well as notions of wildness, otherness, and civilisation. Space to consider diverse practises of care and recovery in action is expanded and extended to the coordinates of Mount Stuart, creating a revised typography – one where past meets present, and alternate cultures and languages speak one unto the other.

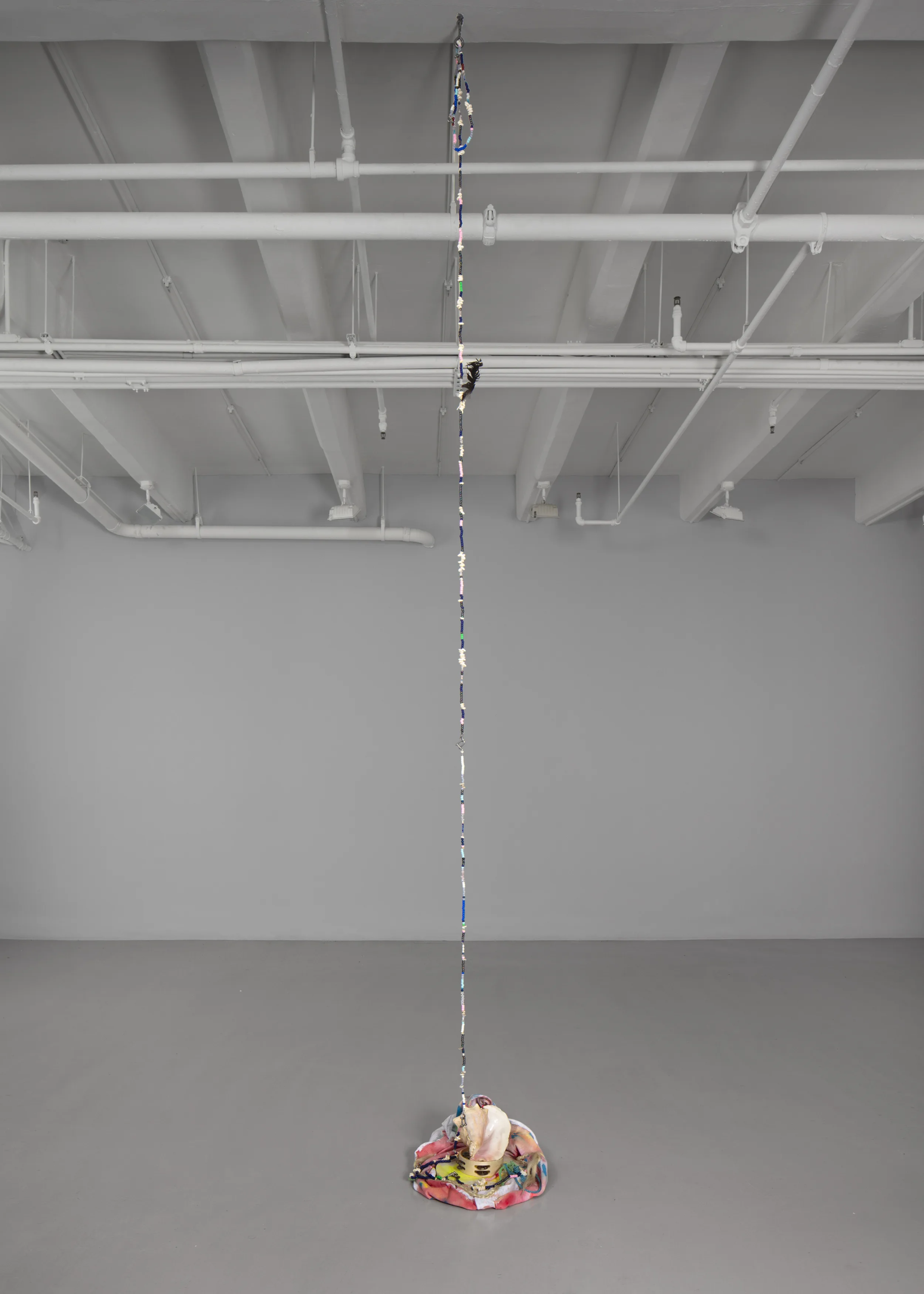

In the Marble Hall of Mount Stuart, recovery is not so much about discovering the story of the actual architectural surrounds, but excavating buried histories, particularly those of womxn of colour. Assemblage-cum-tapestries incorporating tufting techniques, embroidery, carvings and talismanic embellishments feature the languorous limbs and figures of Black womxn, outstretched and in repose amongst water or foliage. Echoing the kind of call and response found in her films, where songs and sounds sonically reach back to past ancestral knowledges and experiences whilst looking forward to future relief and restoration, the assemblages resonate a kind of spiritual reality and release that transcends time and place, yet recalls a state one is inevitably attempting to inhabit and realise in the here and now. Threaded with colourful beads, shells from Bute and Barbados, and castings of bodily parts, these assemblages invite both contemplation and admiration. The evoke spaces and bodies, ecologies and cultural economies, the extend far beyond the Scottish climes. With some included in a later group exhibition, Reverb, at Stephen Friedman Gallery, London, the assemblages evoke aural as well as haptic sensations in viewers. Interspersed with actual doors that are positioned at an angle, Whittle’s assemblages and sculptures in Mount Stuart become portals to, as well as traces of, other modes of being and dwelling. They summon the outside in and vice versa, and push us to discover what is not within sight or immediate sensation.

Unlike her films, however, these assemblages can be directly encountered, not just witnessed. They channel and act on us as much as we tune into and interact with them: “They lead you down particular suggestions or allusions of movement,” Whittle elaborates. Akin to the sequences of dance in her films, which open both dancer and viewer up emotionally, the assemblages and sculptures gesture to physical actions which instigate intellectual and psychic change. “That some of the sculptures are open or closed, suggest that you’re meant to pass through. This idea of encouraging audiences to move, shift, or excavate felt very enriching,” she admits.

Shifts, tilts, actions to ‘kick’ or ‘open’ specific ‘doors’ or concepts are taken to a new level with the ting in the grounds of Mount Stuart. Here physical and emotional transformation is made possible by Whittle’s reinvention of a Norse gathering space or ting, where communities once “assembled, debated, made laws and meted out punishments.” An Assembly or a ting (2024) sees Whittle honour this ancient site by bringing the Barbadian chattle house into contact with the Scottish bothies. Chattle houses were simply made timber-framed structures that were occupied by the formerly enslaved, then freed, tenants on plantations. If disputes occurred, workers were able to deconstruct the house and rebuild it elsewhere. Bothies are also a form of shelter, but are found in remote places in Scotland, have little to no amenities, and are open to anyone who happens upon them. Whittle’s conflation of these two structures not only challenges the pomp and pride of the larger Georgian-Victorian estate with the former’s striking but effective simplicity, but also rebuilds the dynamics and codes of power, by giving visitors – the people – a space in which to think, debate, seek resolution and respite, as well as reserve for communal activities and gatherings. Capitalising on the chattel house’s links to fugitivity and the bothies’ potential to harbour fugitives, Whittle’s humble hut is at once a construction that migrates (it appears as if it has been plucked from the Barbadian coastland and carefully settled in the green grounds of Mount Stuart) and encourages migration and migrating ideas. Through its historical referents, the ting is devoted to the maroon, the fugitive, the migrant, the pilgrim, the vagrant, the chattel farmer, and the worker, the seeker of asylum as well as the refugee. Thus, in fusing two cultures and their landed histories together, Whittle harbours a beautiful exchange within the yellow-walled ting: a trans-Atlantic and trans-continental dialogue that fosters healing as much as learning. Recovery is again felt in the recuperation of the old in order to remake it anew; in the rest such a stop-off facilitates, in the leisure of such a lease-less place, however temporary and transitionary it may be.

Whittle’s spatialization of rest, recovery, and care, envisaged in the humblest but most efficacious of structures, has me thinking about the transformative powers of her work. Looking at images of the ting, I see the transformational and transitional come to bear on this remarkable space. For it is a landed thing grown motional, with walls uncannily moveable, where all sense of permanency grows wonderfully ephemeral and errant. The ting also looks to her latest paintings, where hybridity of place and person, culture and its locations comes full circle to the Barbadian-Scottish artist herself. The art of care, much like that of recovery, often emerges in Whittle’s work as a remix of stories, languages, and objects – of interspecies connections and cross-cultural relations. Care is a house homing fugitive figures fleeing impermanency and precarity to find stillness, shelter, and belonging. Recovery occurs at the intersection of differences and the unifying possibilities this creates for body and mind, individual and community, all of which are held in the frames, structures, and surfaces of her work.

Whittle’s recent show at Nicola Vassell Gallery, New York, pushed further into this hybridity and the haven needed for the most disparate of identities. Towards a motherful loving praxis, we cast seeds into the darkness brought together paintings, films, and sculptures, and built on the artist’s former work where a diversity of techniques was harnessed, and a plethora of forms was celebrated. Interdependence and interrelations between species – human animals and non-human animals – came together in her paintings and in the screening of Whittle’s aforementioned film, A Black footprint. ‘Praxis’ here was not only about allowing what could flourish between alternate beings and forms to come abundantly to the fore, but about what was practised, not just theorised, between art and viewer.

Akin to the assemblages in the Marble Hall of Mount Stuart, the paintings and sculptures in Nicola Vassell recaptured and repaired kinship between that which was traditionally deemed separate – man and beast, culture and nature – thereby disrupting dualistic distinctions to create alternative, blended ways of being, seeing, hearing, and feeling. Materials similarly merged, with clothes, musical instruments, and raffia ribbons trimming, draping, or loosely dangling from her paintings so as to extend pictorial representations and sensations into the surrounding gallery space. In this method, Whittle conflated textures with resonances, visual connotations with their tactile equivalents. The result was not so much paintings of hybrid loci and personae, but works rooted in their potential and plotted hybridity.

Works like Black Cats in Disguise and Piercing the Soul (Blessings From Christian) (both 2025) revel in the power of the hybrid and carnivalesque. Figures clad in ritualistic masks moved within hallucinogenic tropical habitats, accosted by cats or nocturnal revelries. In Black Cats, human and feline are virtually indistinguishable and the ambidexterity of one far outmasters the flex and stretch of another. In Piercing the Soul, masquerade opens a celebrant up to a cosmos of ecstasy, where trees vibe and streams sing in a cornucopia of colour. Whilst the former painting is square and offset with a bell dangling from the far-left corner of its frame (a playful touch), the latter is painted on a circular canvas, fringed with yellow raffia ribbon and studded with wooden diamond and oval shapes. The worlds within – whether of dreamy landscapes or surreal interiors – pulse into view, pulling us into their miniature dramas and disrupting the white cube surrounds of the gallery space.

As multivalent as they are polyvocal, these multimedia paintings elude full interpretation, all the while casting a spell over spectators. Embedded with precious stones, conch shells and beads, the paintings become nets, trapping our associations and enmeshing possible interpretations in their layered surfaces. In this, they offer protection not just open inspection of the ambiguities and peculiarities alive on these electric skeins. As amassments of past histories – like maroons, chattel farmers, indentured workers – Whittle’s paintings celebrate the craft techniques and materials which were once used as forms of resistance, as well subsistence, during colonial subjugation. Reminiscent of the ting and the Mount Stuart assemblages, the meanings of these paintings migrate with each look while their mediums vibrate to their own frequency and score.

Finding the Tempo Before We Begin (2025), nevertheless, tops these two works for accumulation of moods, meanings and mediums. Beginning with a central circular canvas, swirls of lucid green and white against an electric blue background are embroidered further with spheres of paint, doilies and painted tambourine drums. With its lower circumference decorated with raffia ribbon, beaded coils, and larger doilies, Finding the Tempo approaches embodiment and theatrically approximates an overly dressed figure. Wonderfully textured and ornate, the ‘tempo’ and register here is loud and proud, an abstracted painting crafted into a form of draped drama and bejewelled dissent. Decoration echoes the exhibition’s titular ‘motherful’, where superfluity is comfort and care, and cultural codes of craft direct us back to the motherland, to its skills and song of love. This is recovery in action, where scraps and orts of diverse cultural and artistic practises are retrieved and reapplied to form a new language, a new praxis of coexistence, a new place for the coalescence of difference to occur – and in all this, new life, hope, and healing.

I end this deep dive of an essay on this glorious glut of multiplicity and gorgeously realised creativity because this is also part of the reality of care – the collagic windows of Whittle’s films, the migratory potential of her assemblages and site-specific installations, and the carnival of colour and charm that make her paintings. This is the potential of recollecting the past – collecting what’s precious from the clenched hands of yesterday’s trauma so that we can hold it up to today’s light, like a shell found on a desolate beach. This is the care Whittle invests in the underrepresented lives represented in her life-giving works, holding us all in the overlapping instances of grief and joy. And this is what recovery – resting in the trouble as well as from it – often looks like: hybrid, patchwork, unique and uncertain, looking over our shoulders at the world of the past whilst slowly braving the future. Sitting in my sick bed, breathing slowly in, then out, a new body of knowledge flickers into view, another destiny, a ringing sound, a ting of hope that pulls us forward, towards rest.

Written by Hannah Hutchings-Georgiou