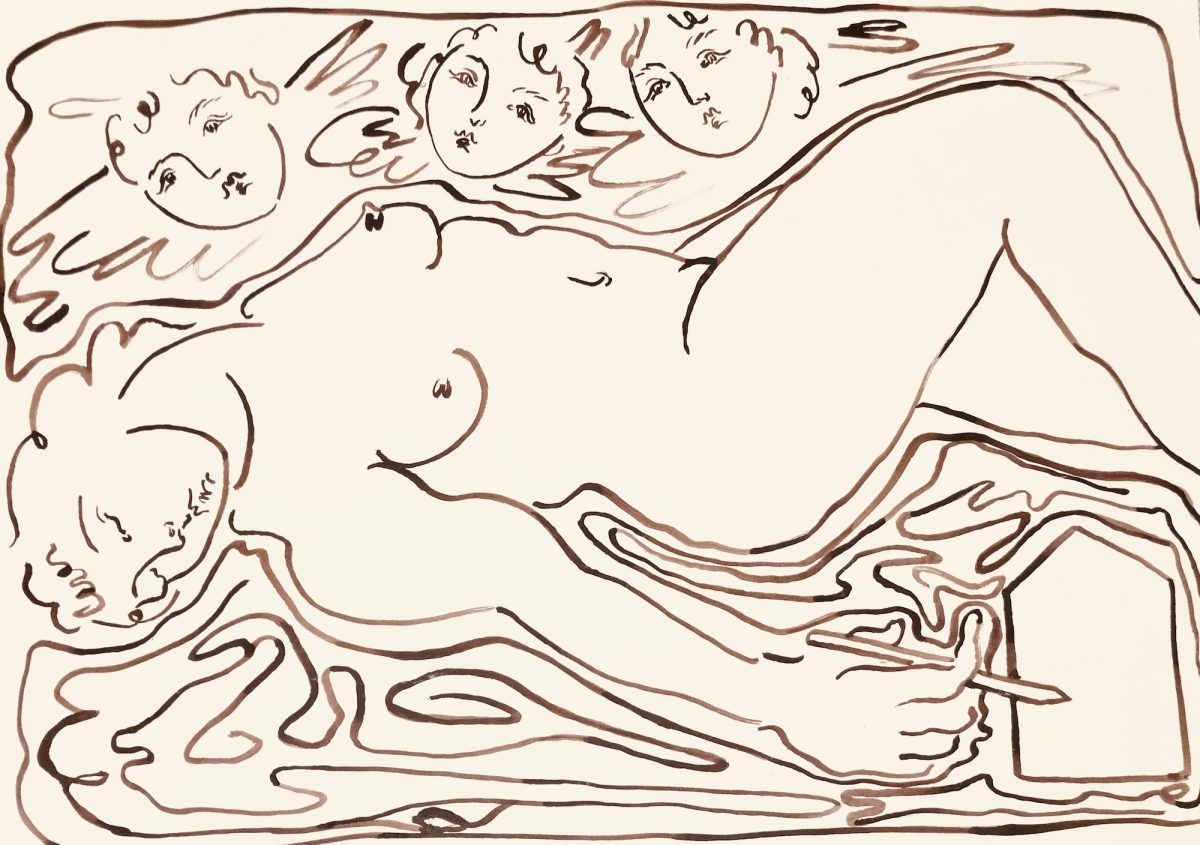

Carolina Aguirre, The Thief, 2021

Open up a map of traditional gender norms, and you’ll find femininity located in private spaces while masculinity spreads across public and professional spheres. Fiercely contested since the 1960s, this staid binary developed new forms during the pandemic as life moved back into the home. In Domesticity and the Feminine

, a group exhibition curated by Joséphine-May Bailey in support of Women’s Aid, 24 female artists respond to the outdated yet persistent association.

“I was considering how gender roles affected our experience of lockdown” says Bailey, who put out an open call on @procrastinarting_, her Instagram platform supporting emerging women artists. “How does unpaid domestic labour get shared when everyone’s working from or confined to the home? Have things got better or worse?” Selected from more than 350 entries, the exhibited works dart between diverse moods, rituals and experiences.

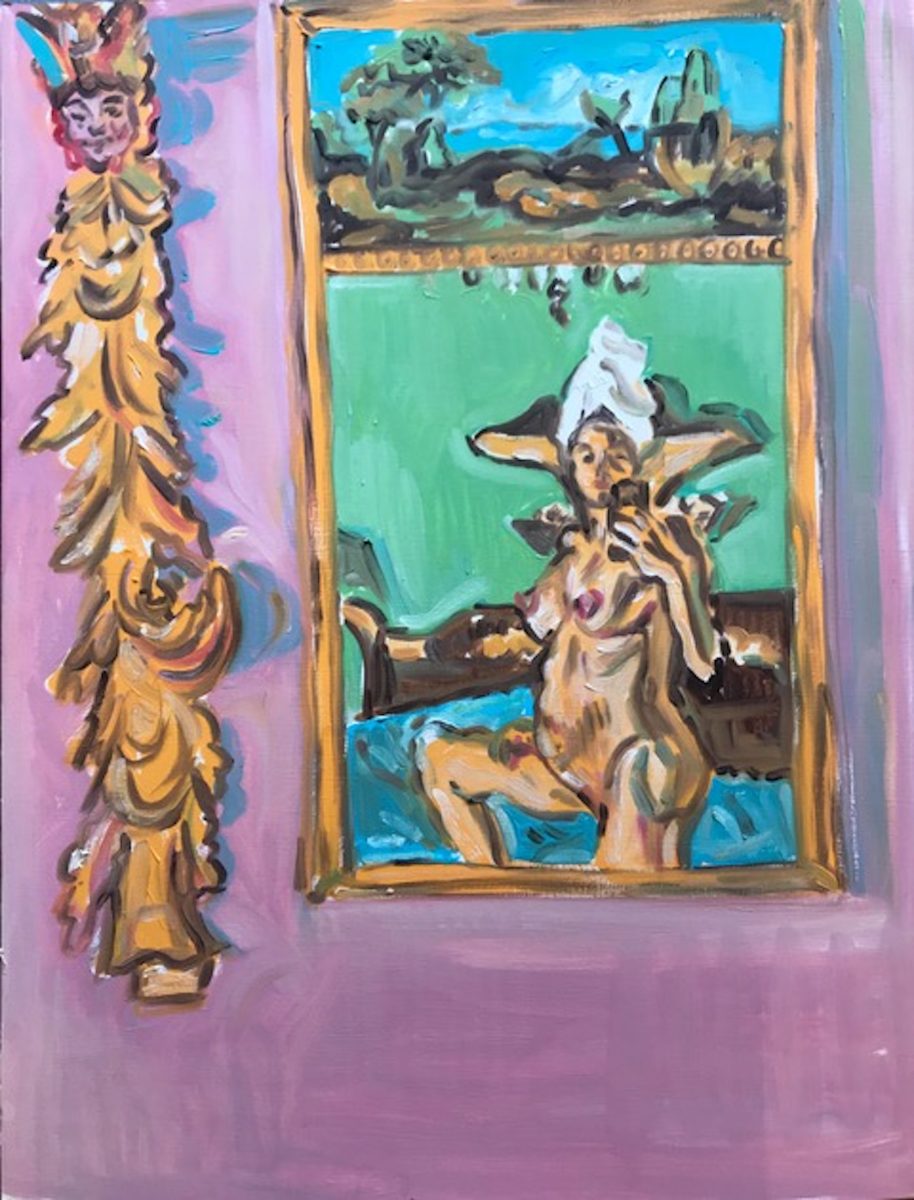

Bathrooms are a recurring theme, replacing the kitchen as the stereotypical domestic arena in which femininity plays out. Collectively, the bathroom is depicted as an awkward space: it’s an intimate realm of relaxation and self-reflection, but it is also one of work, in terms of the beauty routines and ‘self-improvement’ constantly demanded of women. Looking at Henrietta MacPhee’s Self-Portrait feels like walking in on a distinctly private moment. Inspecting her naked body in the mirror as she brushes her teeth, the subject is vulnerable to her own gaze, too: the 2D image warps as it bends around the corners of the ceramic block, hinting at the dysmorphia that can arise from one’s own reflection.

“Selected from more than 350 entries, the exhibited works dart between diverse moods, rituals and experiences”

In Cecilia Reeve’s Hot and Soapy, swirls of shimmering bath water capture the soporific release of a good soak. Bath time is also an indulgent affair for Anna Pogduz’s exaggerated self in Me in a Hot Bubble Bath: her tub overflows with bubbles, her glass with champagne. Presenting what she describes as “modern and monstrous women”, Pogduz hyperbolises femininity and portrays it as something to be bought and consumed. Rhiannon Salisbury similarly situates femininity within a nexus of capitalism, using lurid colour palettes and abstract compositions to parody the beauty standards of mass media.

Subverting those internalised expectations is also a prominent feature. Helena Cardow, a self-taught artist working at the intersection of race, gender and sexuality, invites the viewer to question the power lines that run parallel to sight lines. Lindsey McLean turns a washboard, an object of household labour, into a canvas for a female nude: far from toiling away, her subject is blissed out on sleep.

Sensual and in control, Rafaela de Ascanio’s pregnant lady poses upright for a naked selfie, appearing in contrast to the majestic yet exhausted mother who reclines in Ruby Bateman’s Mothers in Lockdown. Bateman’s tender ink drawings probe the disconnection between the dream and reality of motherhood, especially in response to the unequal share of childcare and homeschooling during the pandemic.

“The bathroom is depicted as an intimate realm of relaxation and self-reflection, but it is also one of work”

Drawing within the confines of a house-shaped box, Bateman’s subject seems desperate for the kind of escape envisaged by Ming Ying and Carolina Aguirre. With fiery colour and thick, distorted strokes of oil paint, Ying conjures up a fever dream of dancing and dynamism. Aguirre’s quasi-mythological scene, in which a birdlike creature bursts forth from a woman’s chest, also promises freedom and catharsis.

These pictures embody what Domesticity and the Feminine does so well. They interpret interiority not just in terms of physical domestic settings, but in terms of emotional and psychological inner worlds as well, spaces rich with creative power and possibility.

Domesticity and the Feminine

Online until 22 June 2021

Image: Rhiannon Salisbury, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, 2021

VISIT WEBSITE