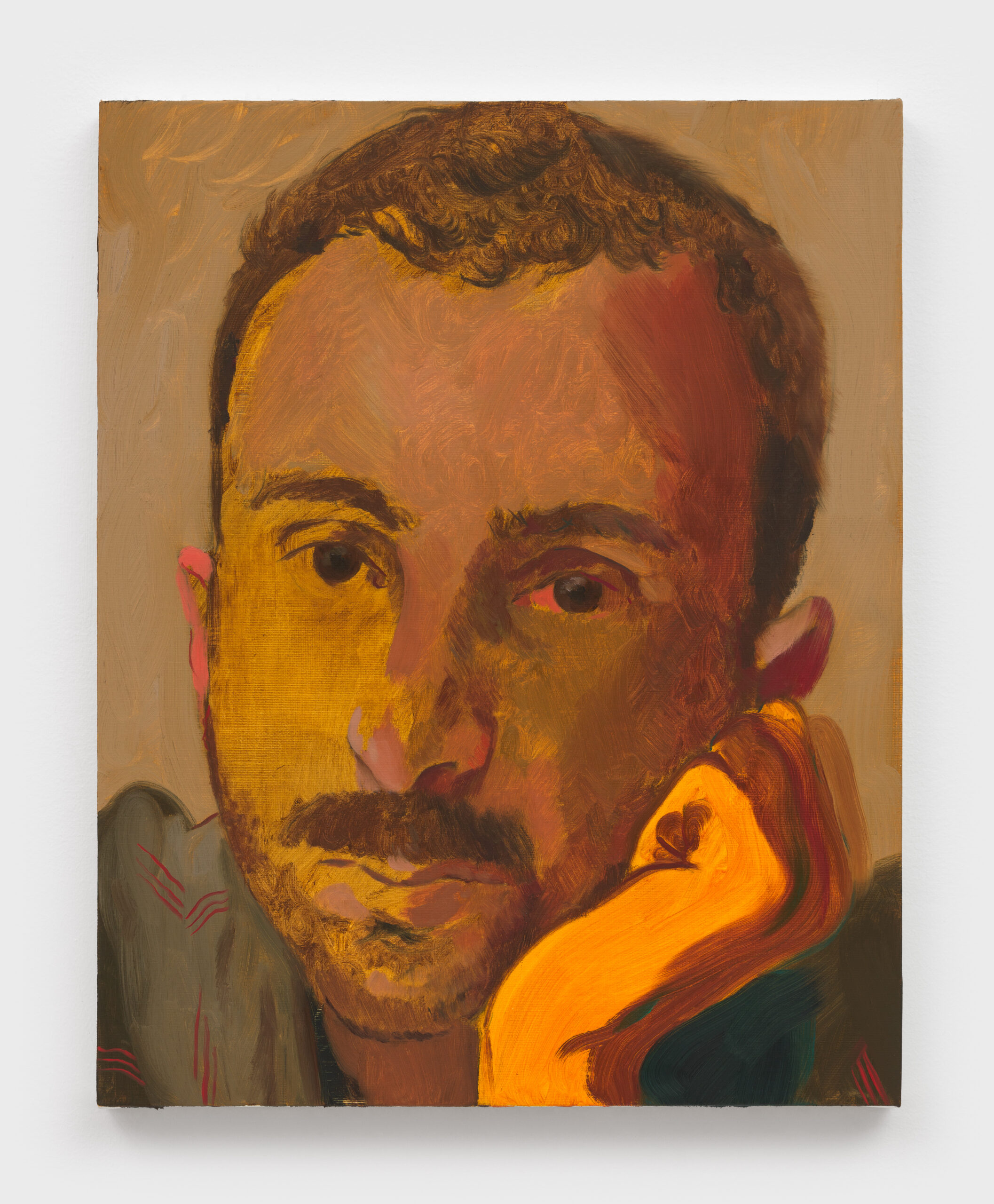

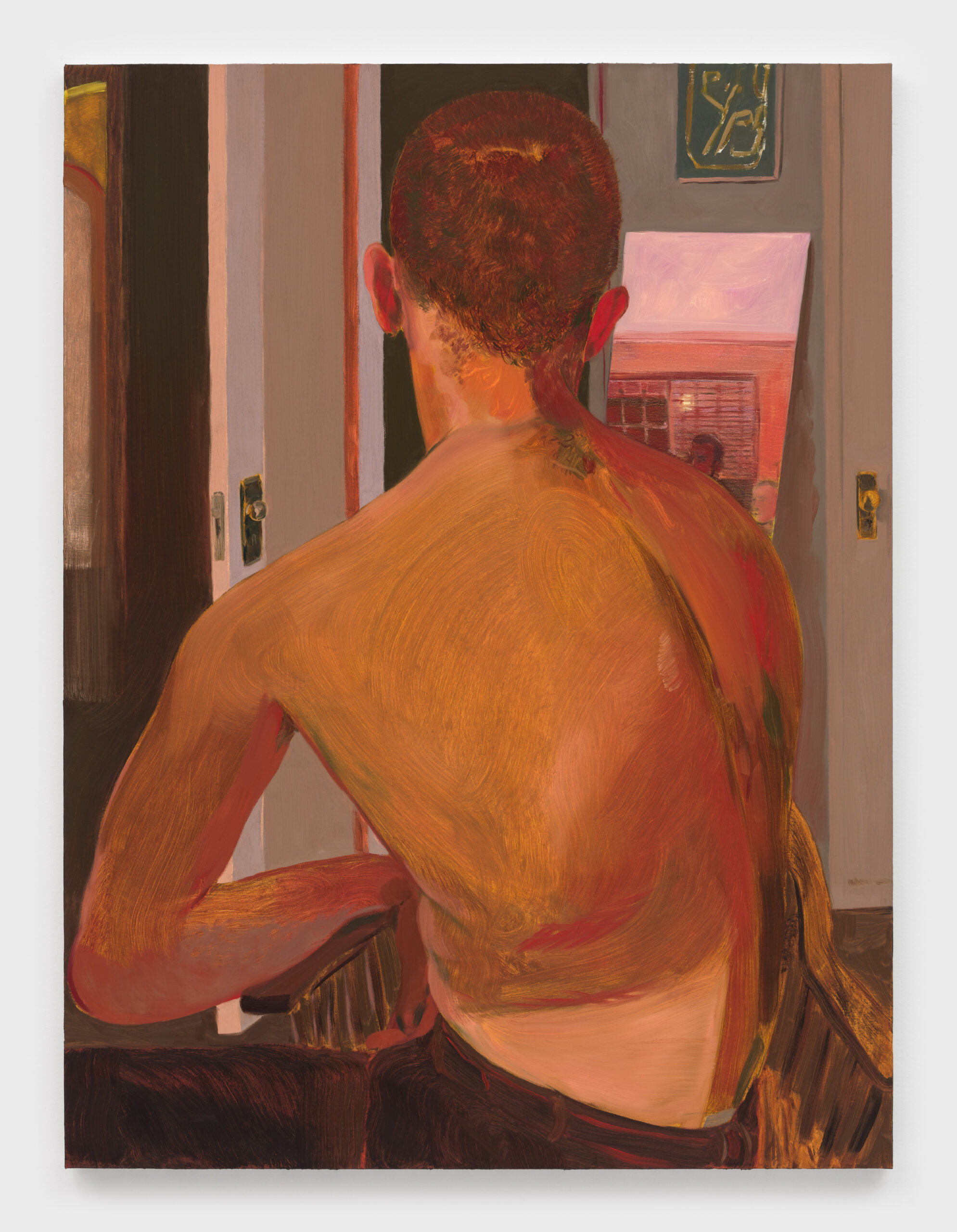

There is something intensely private about artist Anthony Cudahy’s subjects. Their backs often turned to the viewer or their gaze averted. They appear secretive. We see saturated narrations of colour playing out in domestic, and we lean into the subject’s ear, a delicately placed hand or a corner of their temple. Standing before one of Cudahy’s canvases, the figures before us are depicted to feel almost within our reach so that at any given moment, one could extend a hand and tap them on the shoulder. This is the well-honed world of Anthony Cudahy, where shadow and colour meet to invite us into scenes we might not feel entirely welcome to but cannot help but gaze upon.

Those lucky enough to have visited his most recent London show in collaboration with both GRIMM and Hales Gallery will have observed first-hand this exact phenomenon. Cudahy was previously shown at the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Dole and at the Ogunquit Museum of American Art in his native US. But this autumn saw his first UK-based solo project ‘Double Spar’, which showcased a new body of work shared between both Hales Gallery’s Shoreditch location and GRIMM’s Mayfair space.

The show’s title was in reference to the doubling properties of a transparent Icelandic sunstone of the same name. Originally used as a navigation tool by Vikings, spar’s light-polarising property is employed here by Cudahy to explore themes of duality and doubling. Those already familiar with Cudahy’s work will have recognised the warm fuchsias, cool yellows and bright greens which dominate many of his canvas worlds, adorning the walls of both spaces. Perhaps thematically deliberate, the decision to divide this body of work across two locations allowed for committed viewers to journey between both galleries and, upon entering the second location, experience a sense of deja vu. Paintings were intentionally conceived either in pairs or in dialogue with one another, so the divided display spaces added another dimension to Cudahy’s exploration of doubling.

Cudahy first came across this namesake spar stone through its reference in Against the Day, Thomas Pynchon’s 2006 epic novel set in the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. In Against the Day, characters can be split in two using the stone and wander off to lead separate lives. The doubling ‘surrogacy’, as one critic described it, is a central theme to both the novel and this recent body of work by Cudahy.

Dual in both subject matter and in gallery space – Double Spar was partly for Cudahy, a revival of earlier work. Years prior to his London show, he published a group zine based around the same clear stone, which also explored the same themes in collaboration with many artists and friends whom he admired. Revisiting the stone through this new body of work was, for Cudahy, a natural return, or in his own words, ‘like a cycling back’.

Born in 1989, Anthony Cudahy grew up in Fort Myers, Florida, before moving to Brooklyn, New York, at the age of 18 to pursue undergraduate studies in Communication Design at the Pratt Institute. After graduating in 2011, Cudahy would then go on to work a decade in graphic design but, in parallel to his day job, continued painting and developing his own artistic practice. The ability to continue to paint and grow as an artist, developing a deeper relationship with the medium over the years, he explains, was the real gift of his day job. He later returned to studies for an MFA from Hunter College, New York, which he completed in 2020.

For Anthony Cudahy, size matters. In an earlier interview, he describes his awareness of the impact of a painting’s size relative to the viewer’s experience. Small paintings could be seen as intimate objects, calling the viewer inwards. Medium-sized canvases offer a door or a window into their world, whereas large paintings were alternate worlds, wholly absorbing realities. When asked to expand on this, Cudahy explained that given the figurative nature of most of his works, the viewers’ reaction is, of course, somatic – but he reaffirms his earlier thought: smaller paintings are an opportunity to develop a one-on-one dialogue with the viewer, whereas a larger work allows for a what he calls “a different kind of imagining.”

Regarding his current painting process, Cudahy finds that working consistently and following his impulses with research breeds the best results. Much like a musician creating songs for an album, by working in groups of canvases, Cudahy allows for thematic influences to occur more organically. This grouped approach to his own works is something he has found to be more fruitful in allowing for conversations between the individual works to develop. “I like them influencing and changing each other across weeks and months”, he explains.

In his most recent work, Cudahy’s practice has also seen him bring a group of canvases close to completion — and then finishing with ‘one or two crazed painting sessions’ where several pieces are completed at once. This dialogue between his canvases is one of the great joys of viewing his work in its intended clusters, allowing us to draw lines and comparisons relating one piece to its intended other.

Another component in understanding Anthony Cudahy is acknowledging the work which he diligently carries out before executing a canvas. His ability to infuse intimacy into his subjects is undisputed, but the true magnetism of his work is rather his meticulous selection of references chosen to be brought to life together on canvas. Integral to his painting and drawing practice is an extensive research process which serves to develop and inform his work. Collected diligently, his references range anywhere from film stills, classical masterpieces, hagiographic icons, historic sites, and family photographs to social media screenshots. Cudahy does not shy away from this but rather comfortably leans into his references — they are matches igniting his workflow. His ideas and figurative concepts always start from other images which he collects and saves until the moment feels right, and they appear in the broader dialogue of his work. “I often get the start of an idea like a seed and am patient with it, waiting for images or more context to flesh out the concept”, he elaborates.

Amongst his more classical references, we can find the likes of Titian, Perugino’s St Sebastian or Pieter Breughel (who specifically features in Double Spar using the repeated motif of the foot without a shoe) all interwoven into the depiction of his subjects. More contemporary references include Billy Sullivan, EJ Hauser and, most significantly, the photography work of his great uncle, Kenny Garner.

Given the queer narratives and intimate scenes that play out through many of his works, one might speculate where is the boundary between the external references and Cudahy’s personal world? When asked whether scenes from his own life were hidden amongst his works, he shares that his paintings can be a record of sensations experienced by him but that he intends for his works to be received as open-ended generative spaces. Although Cudahy admits to using his medium to reorient certain of his own life events and emotions, he is not the focus of the subjects portrayed in the hopes that viewers might still be able to superimpose his own experiences into his work. He does confirm that certain of his own life events have helped make sense of or can be paired with images from his research. “Painting itself is such a self-referential medium’ he admits. “I’m less interested in reinvention or newness and more with a conversation across time.”

When considering Anthony Cudahy’s practice as a queer artist, it is also important to consider the work of his husband and frequent collaborator, Ian Lewandowski. As the archivist of Kenny Gardner (Cudahy’s great uncle), Lewandowski shares his affinity for archival research. The pair collaborated in 2021 to reunite a selection from Gardner’s archive to be displayed alongside Cudahy’s works in an exhibition shown at the Deli Gallery titled It Was Dark in His Arms. This intergenerational conversation between Gardner, Lewandowski and Cudahy was a chance for viewers to glimpse the artist’s work alongside one of his most significant influences. In a 2021 interview discussing the exhibition, Lewandowski mentions the term mondegreen in reference to what he calls an ‘imaginative misunderstanding’ of the past, which can lead to new significances or outcomes. Although in this context, Lewandowski was addressing the queer lens through which he might inevitably view Gardner’s works – the anecdote translates perfectly into Cudahy’s desire for viewers to infuse his works with their own experiences.

Present amongst the works hung at Grimm Gallery this year was a portrait perhaps a little different from the rest. It was that of Arthur Russell, an American cellist and composer who passed away in 1992 of AIDS-related complications at the age of 40. Born in 1951, Arthur Russell was best known for his contribution to the American music landscape and, much like Cudahy himself, was described as being an extensive archivist of his work and research. This homage to the cellist is part of an ongoing series of Cudahy’s, which has seen the portraiture of several artists and creatives lost to the AIDS crisis.

In the painting, we see Arthur playing the cello, his one foot bare and bathed in a pink stream running horizontally to the bottom of the canvas. The shoe missing on one foot is a Brueghel reference, but the rest of the scene is taken from a photograph Russell’s father took of him during a family vacation during which Arthur brought his cello onto the beach to play. Slicing the canvas in half is the bow, which extends beyond Russel’s hand and is contrasted by the tender corner of Russell’s shoulder, in which we see the pink of his flesh nestling the cello.

When asked what initially drew him to Russell as a subject for his work, Cudahy spoke of the period during which he had first moved to NYC and which coincided with the reissues and release of Arthur’s archive. ‘He was that magical phenomenon of on first listen of any song, it being nothing like you’ve heard before and intimately familiar.’ Regardless of the genre, Cudahy was particularly touched by Russell’s unpretentious lyrics and distinctly unique soundscapes.

The magic of Cudahy’s work is the humanisation it brings to his subjects. His ability to invite life through colour, to generate the feeling that you might just be able to reach out and touch the figures through the window of the canvas, is a particularly stirring one, especially when applied to the lost AIDS generation. They live on through this series of Cudahy’s work, which serves as both a homage and a rebirth for a whole cohort of artists lost too soon. Despite this period in history marking a particularly sombre passage for queer creativity, Cudahy’s work breathes a sense of hope into the past.

Words by Mélanie Steen. Arwork images courtesy Grimm Gallery and the artist. Installation images courtesy Damian Griffiths.