The Middle East, used to describe the region stretching anywhere from Afghanistan to Egypt, is an inevitably fraught term. A colonial invention, like many of the names invented by the Empire to secure territory at their whim, it is woefully outdated. Reflections, a new book published by The British Museum, considers this terminology and showcases contemporary art specifically of the “Middle East and North Africa” region. The author, Venetia Porter, who was raised in Lebanon by her mother (the fashion designer Thea Porter) is curator of Islamic and contemporary Middle East art at the British Museum.

In her introduction, she muses on the difficulties that stem from labels, citing the art historian Fereshteh Daftari, who was one of the first to articulate her increasing concern at the use of the word ‘Islamic’ as a definition for the modern and contemporary art from the region. “‘Islamic’ has long been used to define history, literature and art from the territories that range from West Africa to Southeast Asia, where Islam as a religion could be said to provide a linking thread. The problem is that the term perpetuates notions of a single identity, implying a unity within the vast output of production from across this slice of geography, sometimes described as the ‘Islamic world’.”

Porter goes on to interrogate the term “Arab art”, which can be used to refer to work from 22 individual states from Algeria to Yemen. Porter suggests that generalising terms should be used with caution as they present the danger of othering. She concludes that using the term Middle East, which alone has colonial connotations, and pairing it with North Africa, as a “loose way of indicating an association with a region… seems less constraining and prescriptive.” However, art historian Nada Shabout argues in the book that “a sense of Arab identity was forged in the mid-twentieth century as an ideological weapon of resistance against colonialism”. She points out that Arab artists in many cases share the same preoccupations, such as the effect of the Arab defeat by Israel in 1967, despite their divergent histories.

“The Middle East is a colonial invention, like many of the names invented by the Empire to secure territory at their whim”

It’s against this backdrop of identity-wrangling that 170 artists are featured within Reflections. The book splits itself off into different chapters examining topics such as Faith, A Female Gaze and Figure and Figuration before a mammoth section on Political Struggle, Revolution and War, which is subdivided into different countries. The grouping of visual elements is impressive, demonstrating the range of artists’ interrogations of the figure, or their diverse takes on abstraction and script. Chapters such as Past is Present and Faith, which unite work under a single theme, are bold in their categorisation but present a fascinating take on interpretations of a subject.

Take Shafic Abboud’s multi-modal Nu, composed of gouache and charcoal around 1969. Abboud’s sensual depiction of a figure borders on the abstract; his daughter Christine describes his nude figures as being “‘erotic… but with no anatomical details. It is the curve [of a line] or the shade of a colour that creates trouble for him’”. This attention to painterly, instead of verbatim elements of a work is echoed many years later in Tahar Mguedmini’s Untitled 2012 work, where black pastel hints at a powerful man leaning over smaller shadowy figures. The intimation of what is there, rather than a literal depiction, clothes these artists’ work in the beauty of secrecy.

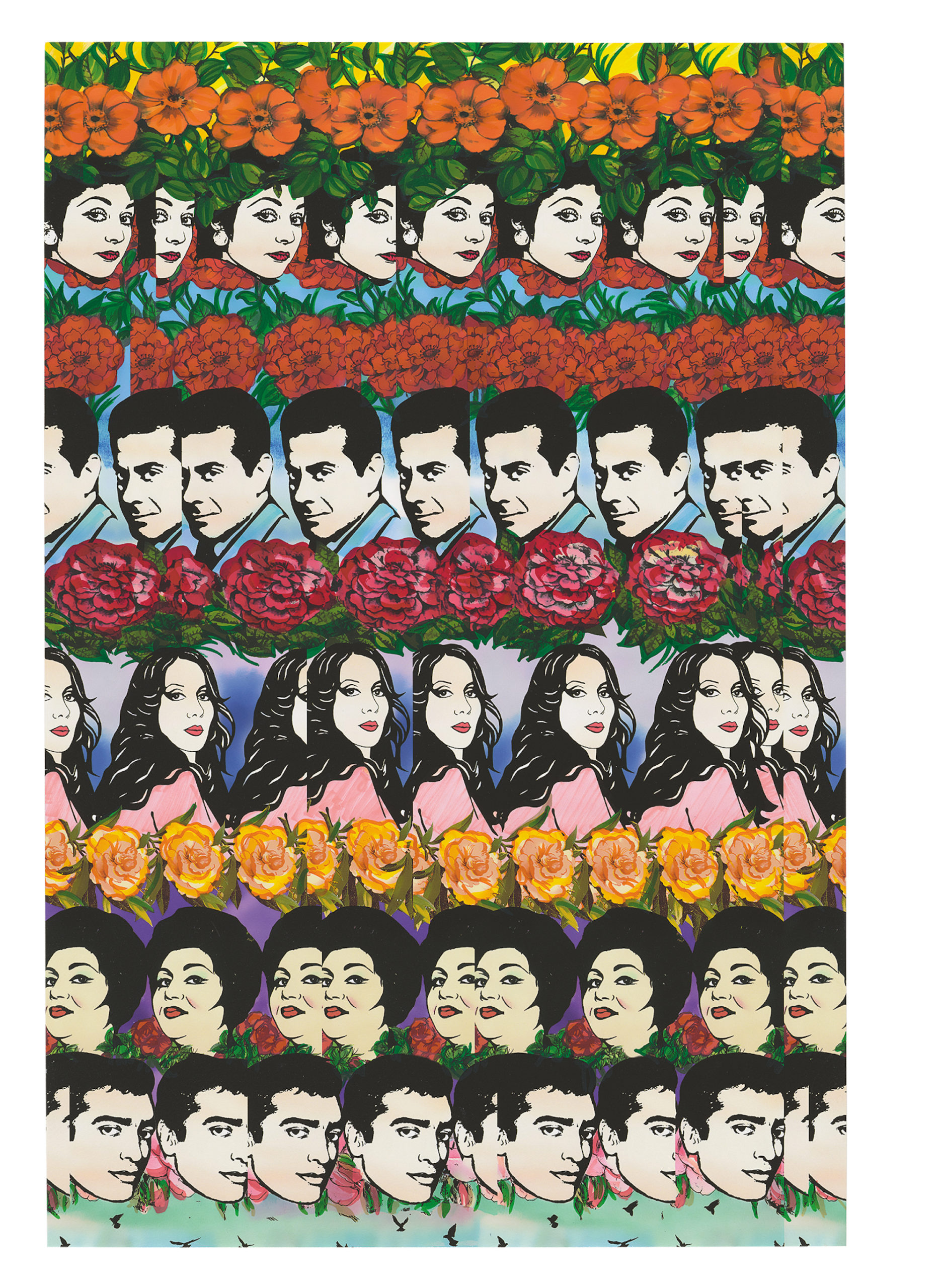

Left: Tarlan Rafiee 30 Years, 2015 Hand-coloured giclée print from a portfolio of ten prints made with Yashar Samimi Mofakham. Reproduced by permission of the artist

Tarlan Rafiee’s The Female Gaze delves into representations of pop culture with a print from the series 30 Years, produced in 2015. It lavishes the faces of celebrated musicians and actors from the Middle East in a pop art aesthetic, intermingling the figures with blooming roses: “Each of these people played an important role in their society. They rebelled against what society expected from them… they represent free will.” Hengameh Golestan’s photograph, from her series Witness 79, documents a demonstration on 8th March 1979 where more than 100,000 women took to the streets of Tehran to protest the enforced wearing of the hijab, one of the impacts of the Iranian Revolution. “We were actively taking part in shaping our future through actions rather than words,” she says, “and that felt amazing.” Although Golestan developed the film, the photographs were never printed and remained as negatives until 2015.

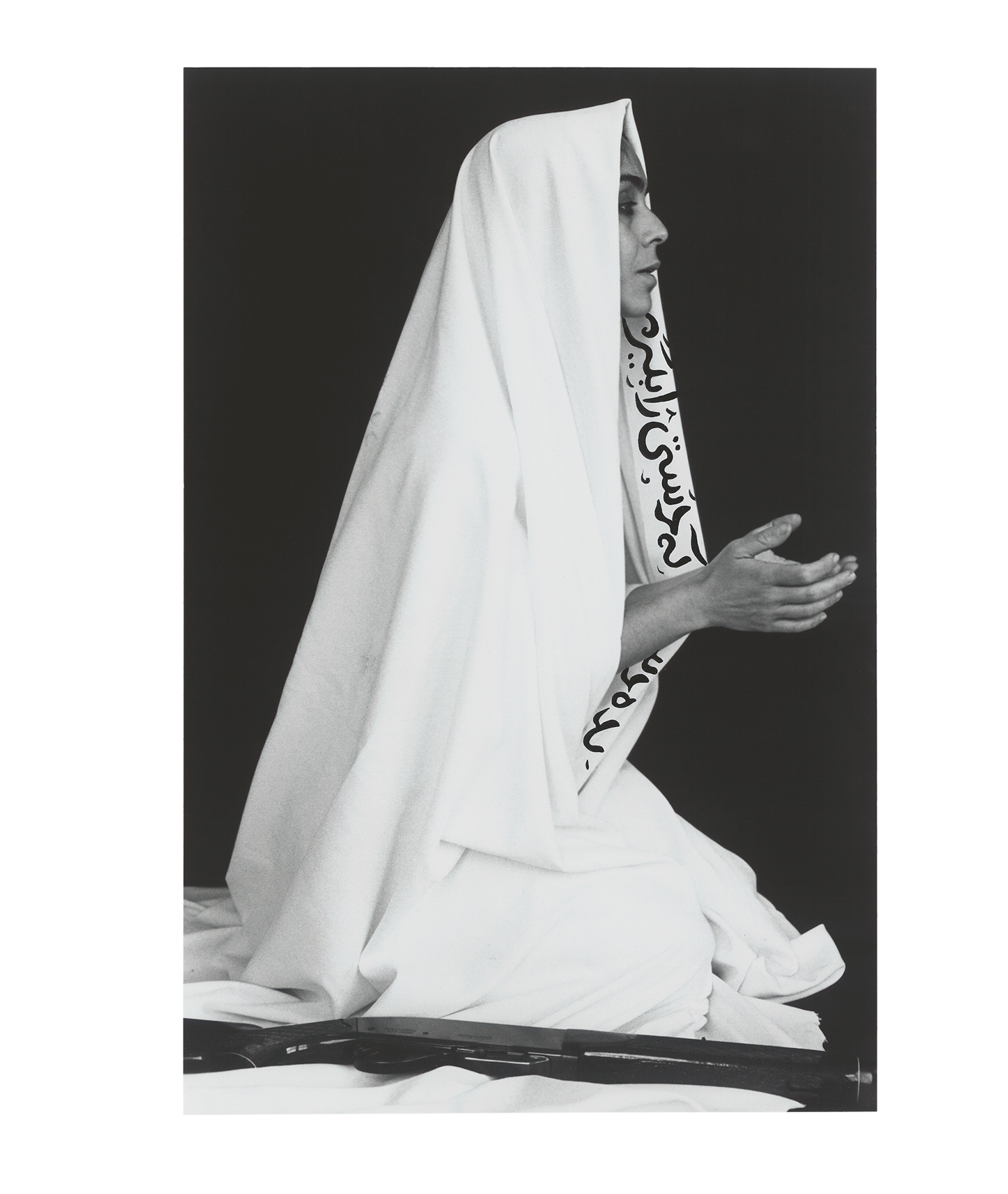

On the opposite page, a work from Shirin Neshat’s series Women of Allah negotiates the gulf between the Iranian post-Revolutionary state and her pre-Revolutionary upbringing. Handwritten text snakes down the side of a kneeling woman’s pristine white hijab, her eyes half closed. Art historian Layla Diba explains that Neshat’s work is steeped in Persian literature, “from the feminist poetry of Forough Farrokhzad to the classical poets.” The words are in fact Neshat’s own: “‘Give a hand so I can be held’”, while a gun beside figure evokes the female fighters of the Iran-Iraq War.

“Reflections is an ambitious, wide-ranging tome, but it is almost impossible to survey the length and breadth of a region saturated with such diversity”

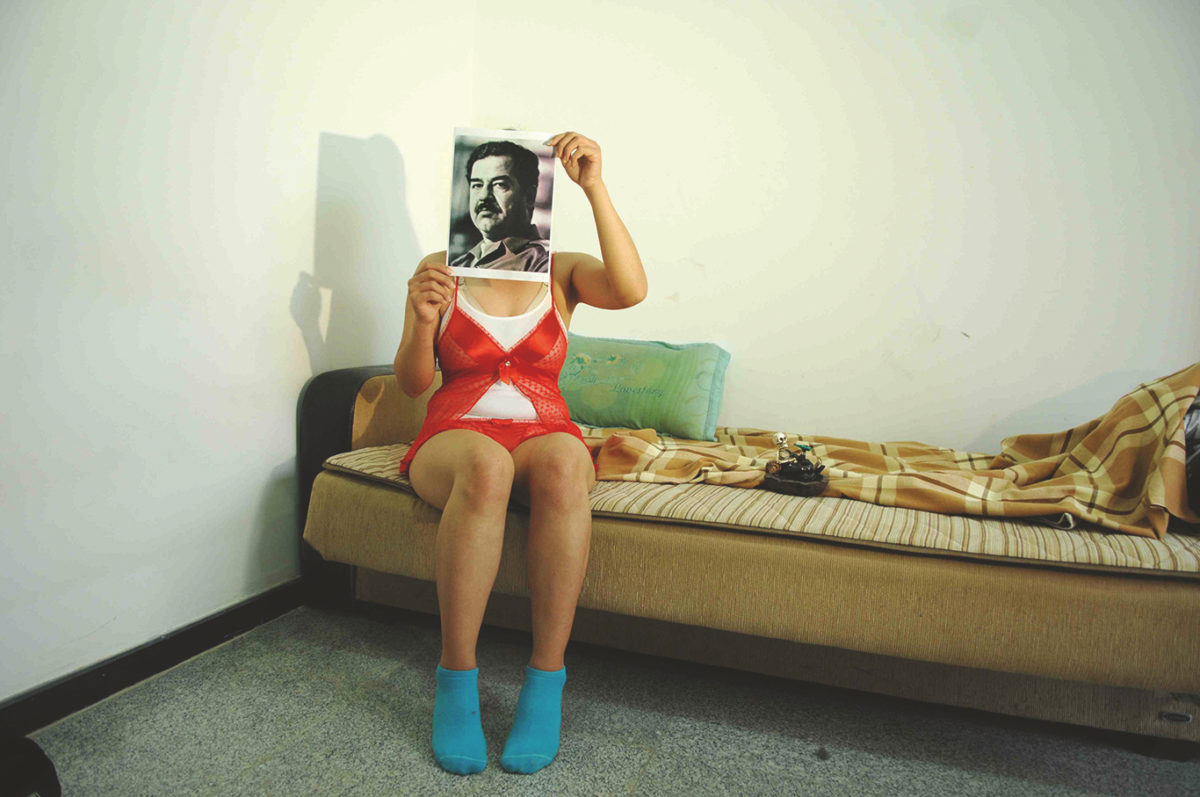

- Jamal Penjweny (born Sulaimaniya, Iraqi Kurdistan, 1981) Saddam is Here, 2010 Photographic prints, numbered 4/5 Reproduced by permission of the artist. Courtesy Jamal Penjweny and Ruya Foundation

Reflections is an ambitious, wide-ranging tome, but it is almost impossible to survey the length and breadth of a region saturated with such diversity in history, culture and politics. How can one book do it justice? Reflections finds its purpose as an archive of contemporary art from the Middle East and North Africa, and provides a gateway for students and teachers to diversify the art canon.

While the book will be useful as a means of discovery on artists and their relationship to the region, particularly in educational contexts, readers should look beyond and also engage with the work of artists from the MENA or WANA (West Asian North African) regions on their own terms. One jumping-off point is the WANAWAL (The West Asian and North African Women’s Art Library), run by artist Evar Hussayni as a publicly accessible digital archive which collects art work and curatorial projects by women from the WANA region.

It would be amiss to say that Reflections is an attempt to decolonise art history—it is impossible to remove the fact that it’s published by the British Museum. This colonial positionality is what makes it difficult to engage with the book authentically; it has only been, as the timeline at the front of the book reminds us, not much more than half a century since the British occupied many of these countries.

Reflections: Contemporary Art of the Middle East and North Africa

Published by The British Museum, November 2020

VISIT WEBSITE