When British Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare

was invited to coordinate this year’s committee for the Royal Academy’s annual Summer Exhibition, he immediately knew what he would do.

“I wanted to show the works of artists who have been left out of the canon of Western art history,” he explains over the phone, two weeks before the opening of the 253rd exhibition. “Artists from different parts of the world, self-taught artists, artists with disabilities, artists who stitch and knit. I wanted the exhibition to be as diverse as possible and to showcase a multiplicity of voices.”

You could say that Shonibare simply wanted to build on the very nature of the Summer Exhibition itself (pushed into the autumn for the second year running by the pandemic). Established in 1769, the year after the Royal Academy was founded, it has always been intended as an open exhibition that all artists could submit to.

Each year, members of the public are invited to enter new and recent work. This is reviewed and the successful entrants are hung alongside works by Royal Academicians, Honorary RAs (including some of the biggest names in global art) and specially invited artists. Almost everything is for sale and the RA takes 30%, which goes to support the RA Schools. In many ways, the Summer Exhibition is about one generation of artists supporting the next.

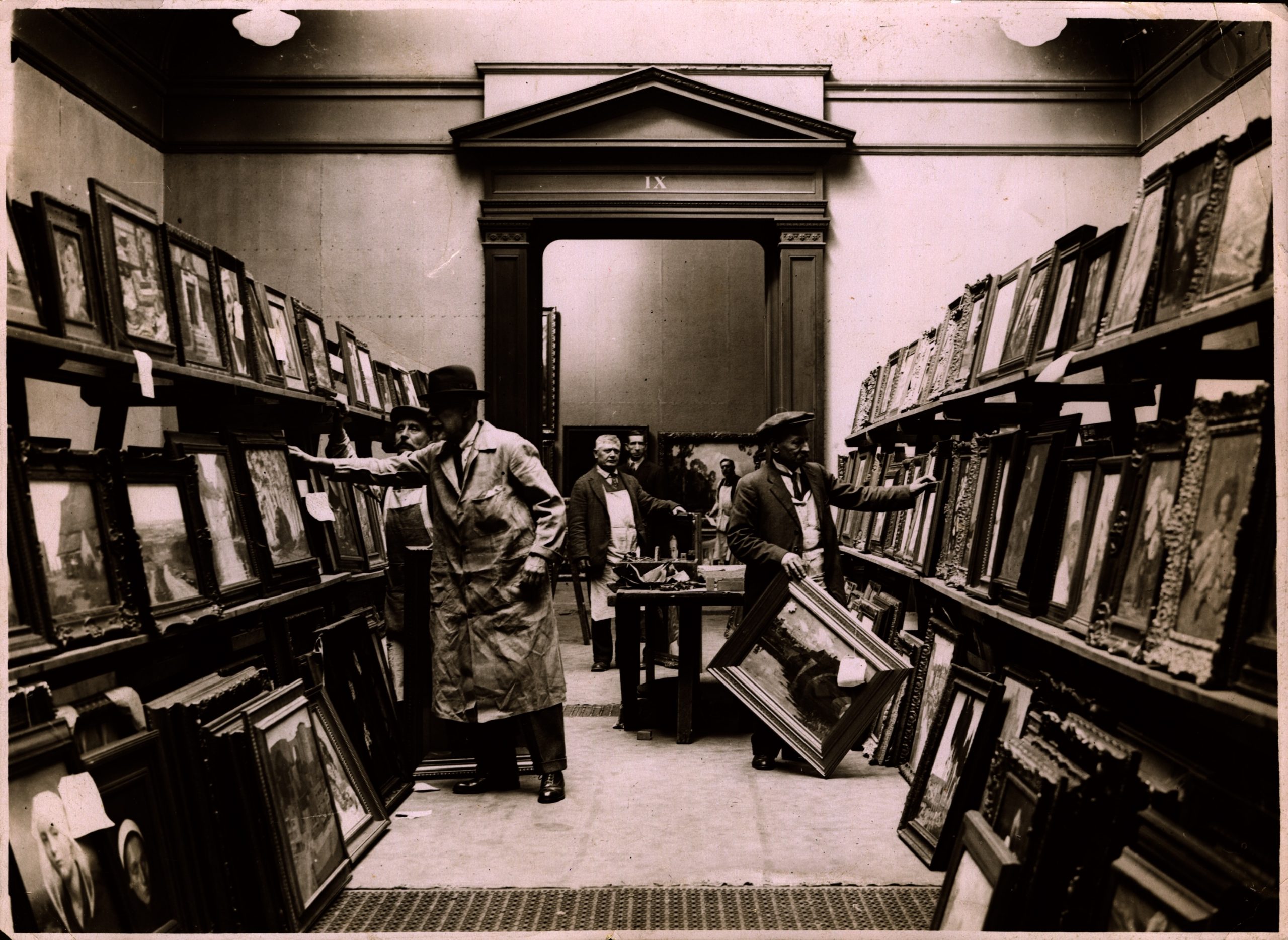

This year, a committee of seven Royal Academicians has whittled down some 15,000 entries to just 1,382. Thankfully, the selection process has evolved since 1769, even since 1999, when Paul Sirr took on the herculean task of managing the show’s administration. “When I started, artists delivered thousands of works to the building for judging and they were manually catalogued in the vaults,’ Sirr remembers. “In the old days, handwritten, often illegible and incomplete entry forms were delivered by the sack load.”

These days the call for open submissions goes out in the New Year and closes in late February, after which the committee sifts through the initial entries digitally. The list is trimmed to a reasonable number (between 1,500 and 2,000 works) and the shortlisted entries are delivered in May for the second and final selection, which takes place in person. At this point the entries are barcoded and stored in state-of-the-art conditions.

“It’s all much more manageable,” says Sirr. And despite the unfavourable odds, all it takes is one ‘yes’ and a work is through.

Another thing that’s changed is the presence of women in the room. Rebecca Salter, the RA’s 27th (and first female) president comments on a documentary film of the Summer Exhibition of 1976 that’s floating around on YouTube. “They’re all men, they’re all chain-smoking, they’re all wearing tweed,” she says, laughing. “It looks a little different today.”

Summer Exhibition (install), 2020. © Royal Academy of Arts / David Parry

The president always chairs the Summer Exhibition committee, and this year is Salter’s second outing. She describes the hanging of works, which are divided up between the Royal Academicians, each of whom curates a room. “Initially, you think, what am I going to do?” she says. “Then you start putting together one wall on the floor, and moving things around, a bit like 3D chess, and you climb up the stepladder and look down from above, and you realise, yes, that’s it. There’s something magical about that and about doing your best for each picture.”

“Every year critics poke fun at the piled-high walls, but the jumble of works is part of the Summer Exhibition’s charm”

It’s a fitting adjective for a show that this year is entitled Reclaiming Magic. The thing Shonibare likes best about his chosen theme is that it’s open to interpretation. “It could refer to aesthetically wonderful pieces, or to something spiritual,” he says. “It could refer to ritualistic objects, totemic things, things that take you to a realm of wonder. It means different things to different people, but ultimately it’s something that’s beyond the ordinary.”

Among Shonibare’s invited artists is Rhode Island-born, Rotterdam-based Ellen Gallagher, whose witty and imaginative works explore racial identity and gender. Gallagher was struck by Shonibare’s proposal of magic at this moment in time, a moment of practical change, and intrigued by the idea of advocating for another kind of space.

“I’m interested in the undercurrent of violence that’s always there in magic, and to repurpose that at this moment seemed very vital,” Gallagher says. “I wanted to be a part of it.” She’s showing Elephantine, a map of pre-Independence Africa suspended between two wooden poles painted in the colours of the Belgian flag, which she made after researching the violence of Belgian colonialism in the Congo. Emerging from a linen covering is the head of an elephant, an animal often brutalised by mankind.

“There are certain things that constitute validation in the public consciousness, and this is one of them”

While Gallagher has participated once before, fellow invited artist Jade Montserrat is making her debut this year. “There are certain things that constitute validation in the public consciousness, and this is one of them,” she says. The young Black artist presents Entered Her Room, a small watercolour of stone carvings sprouting like trees from a mound inspired by a hill near her childhood home in rural Yorkshire. “Our household was shrouded in a lot of mystery,” she explains. “I took solace in the landscape. I think it’s an instinctive thing you do as a child.”

Like most first-time exhibitors, Montserrat is familiar with the history of the Summer Exhibition. “Yesterday I got an invitation for Varnishing Day and immediately thought, I need to get my tin of red paint,” she says. At the 1832 summer exhibition, refusing to be outdone by his rival Constable’s vast and animated The Opening of Waterloo Bridge, Turner famously marched up to his own neighbouring canvas, Helvoetsluys, and added a bright-red buoy in the middle of the serene seascape to draw the eye. “He has been here and fired a gun,” Constable later wrote.

Today, Varnishing Day is less about making last-minute changes and more about celebrating. Reem Acason is here to see her portrait of 21-year-old daughter Matilda, which is hanging on ‘the line’ (the bottom row, historically the place to be). Zayn shows Matilda with a defiant expression in front of a two-toned geometric backdrop. “My mum’s an Irish Catholic, my dad’s a Muslim from the Middle East,” says Acason. “Matilda doesn’t dress like this: she doesn’t wear a hijab and she’s got tattoos. This is almost her alter ego, as if she had been born there instead of here.”

“Magic means different things to different people, but ultimately it’s something that’s beyond the ordinary”

Every year critics poke fun at the piled-high walls, but the jumble of works is part of the Summer Exhibition’s charm. As Sirr says, it’s “eclectic, full of personality and mercifully uncool”. For a member of the public to see their painting inches away from an Eileen Cooper (as in Acason’s case) is a thrill.

“There’s a Barbara Rae on the same wall as mine, which is crazy,” says 30-year-old Michael Bartlett, a technician in the art department at Latymer Upper School in London and the creator of Night Drive, a luminous blue etching and monoprint. On Varnishing Day, the friendship that springs up between 22-year-old Issy Norris and 70-year-old Paul Tonkin is testament to the exhibition’s all-inclusiveness.

Of course, it could be even more diverse, which is where Shonibare comes in. As well as showcasing artists from the African diaspora, he’s shining a light on those moving beyond traditional mediums. He’s introduced a sound programme, with work from radical artists such as Black Obsidian Sound System. The exhibition is usually limited to living artists, but this year the first thing you see is a bold red wall hung with works by the late African American artist Bill Traylor, who was born into slavery and in his 80s taught himself to draw and paint.

The world’s oldest and largest open-submission show, the Summer Exhibition blurs boundaries when it comes to age, genre, background, what art is, and what makes art good, or great, even. It’s at once fun and thoughtful and human and serious. And in Shonibare’s capable hands, it’s transformative, too.

Chloë Ashby is an author and arts journalist. Her first novel, Wet Paint, will be published by Trapeze in April 2022

Royal Academy of Arts Summer Exhibition

Royal Academy, London, 22 September 2021–2 January 2022

VISIT WEBSITE