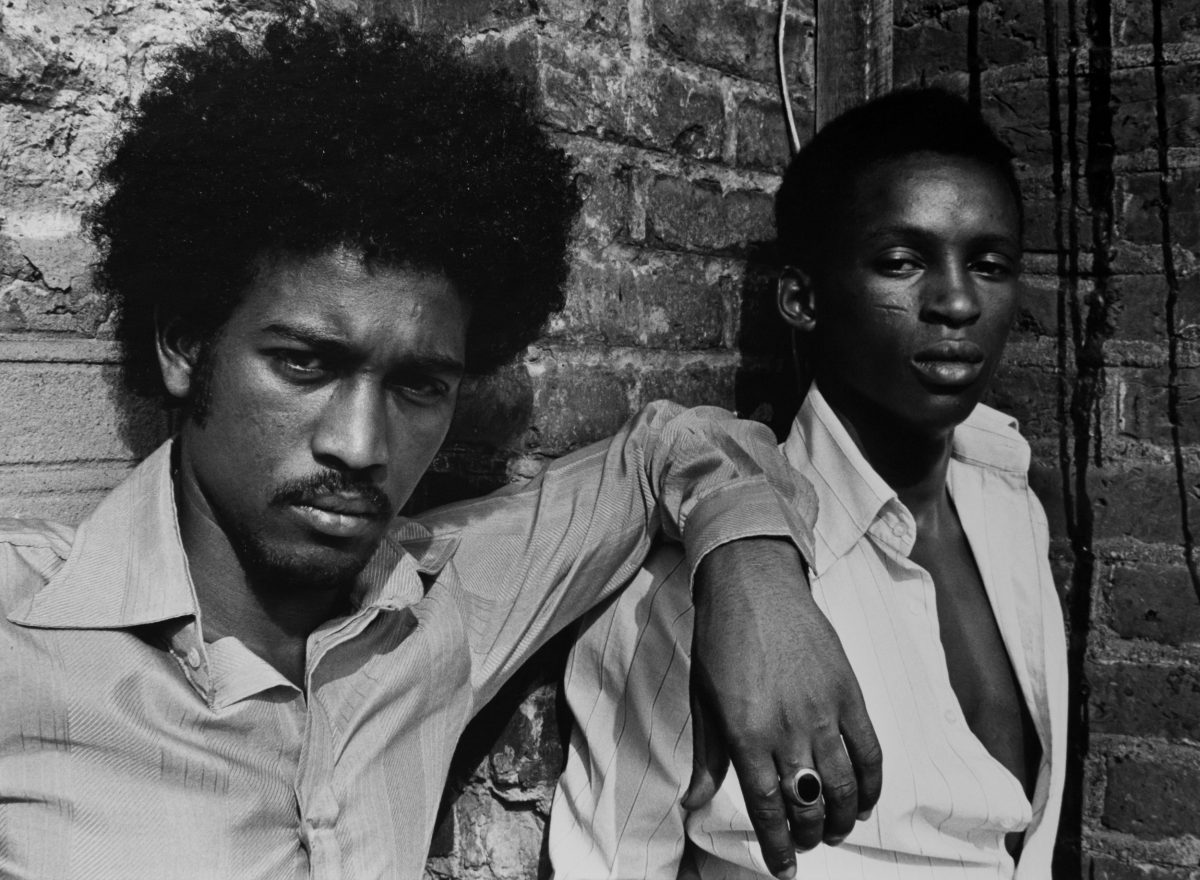

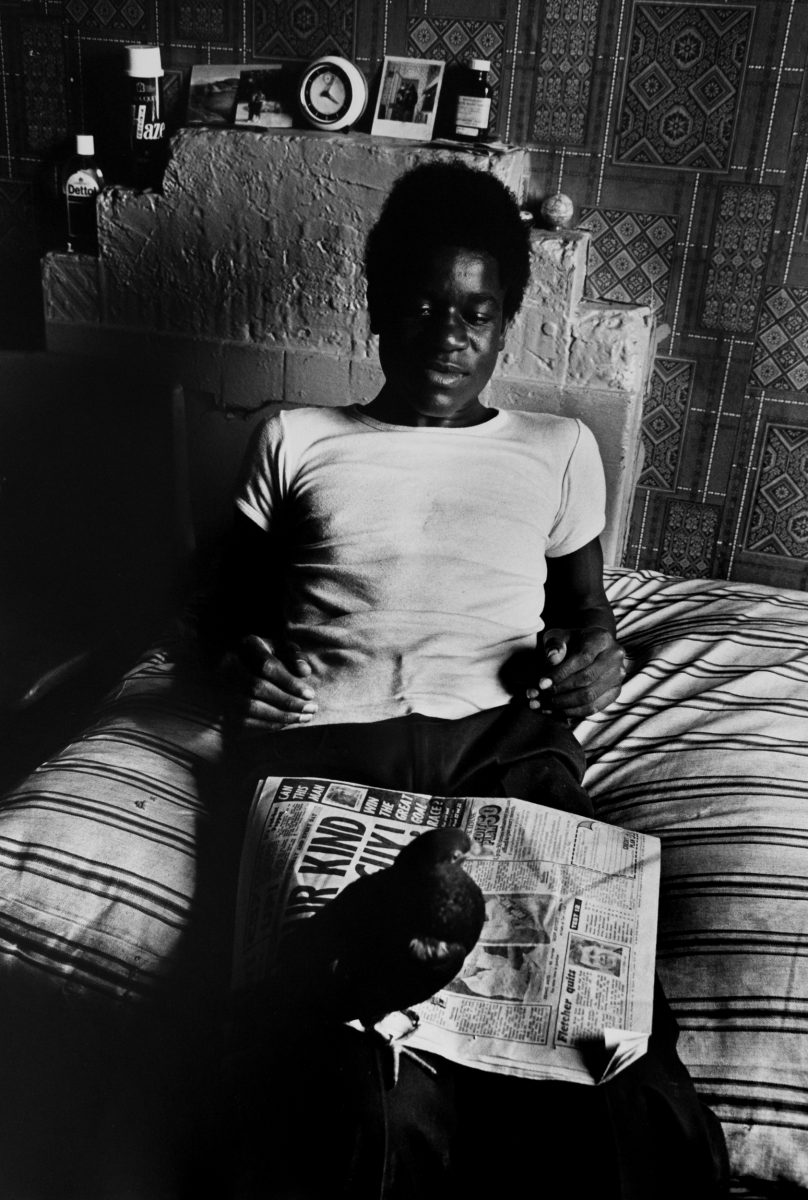

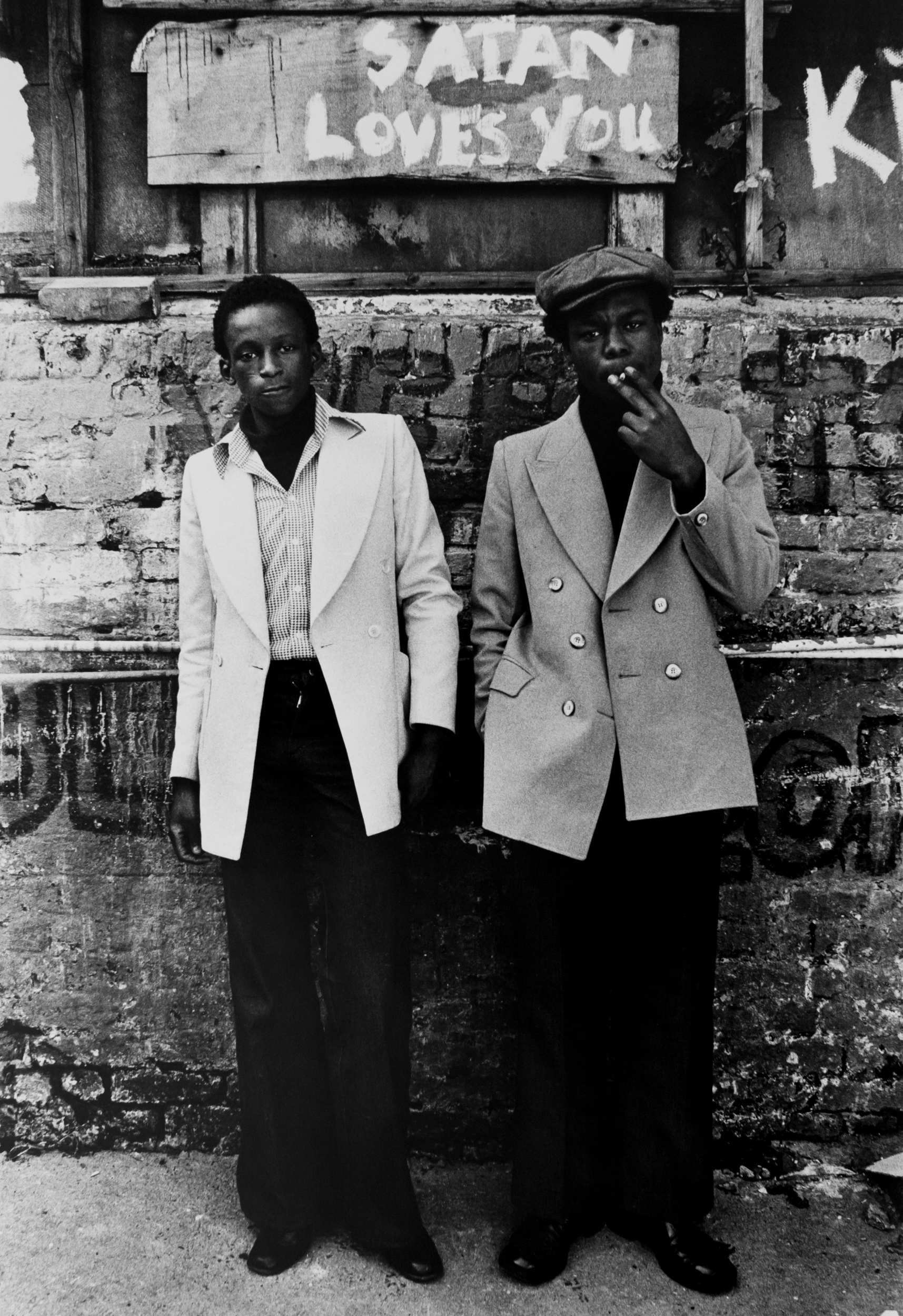

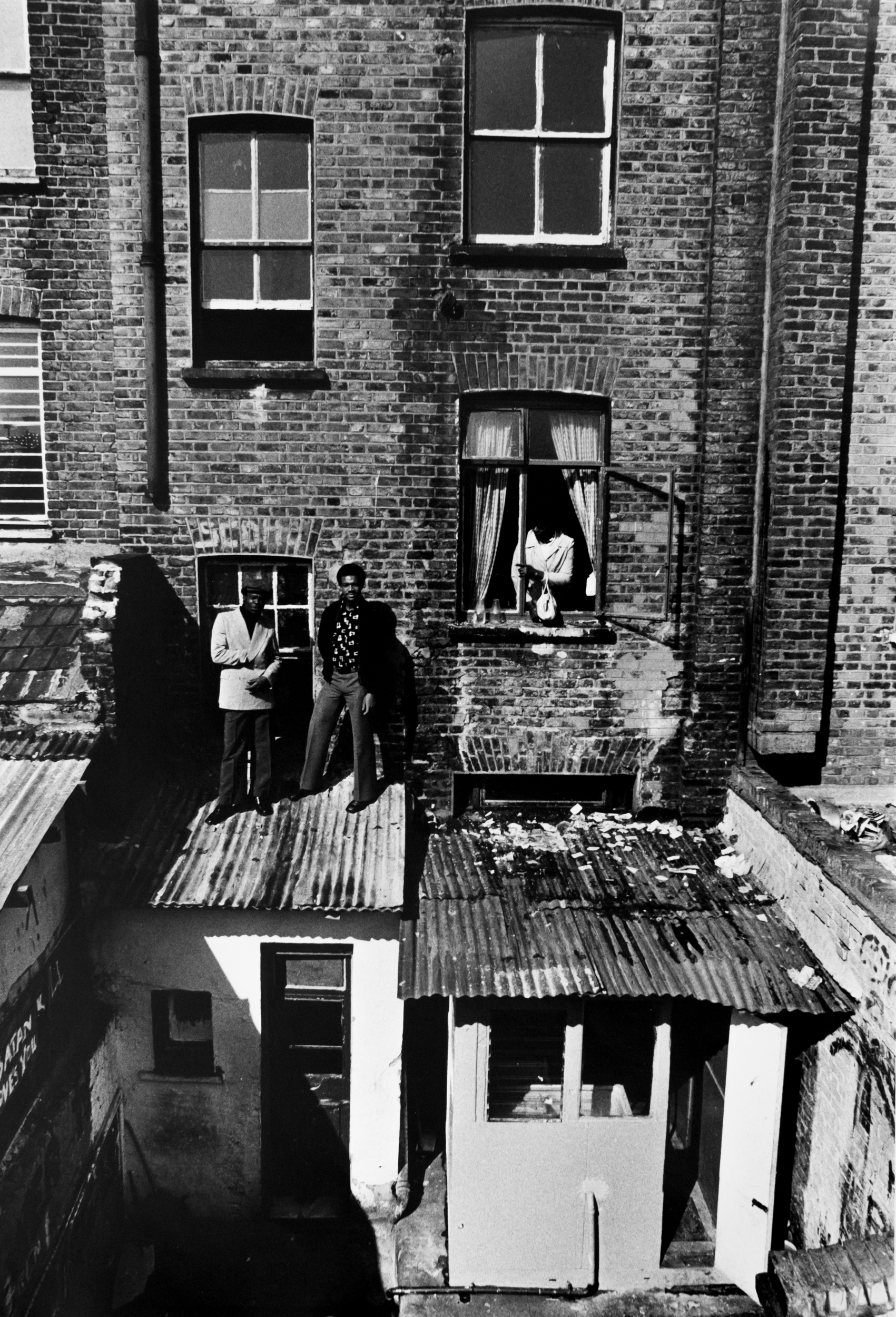

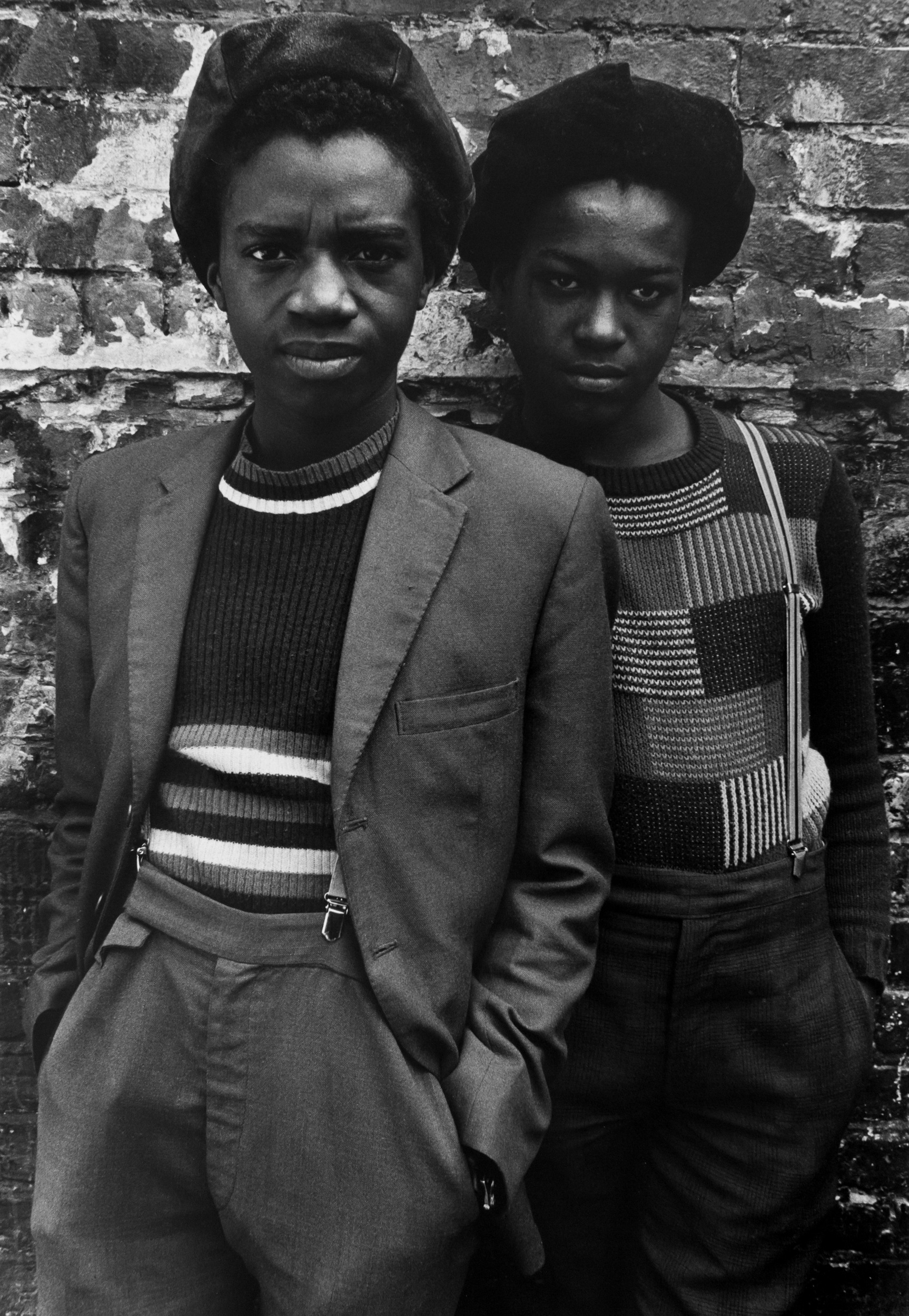

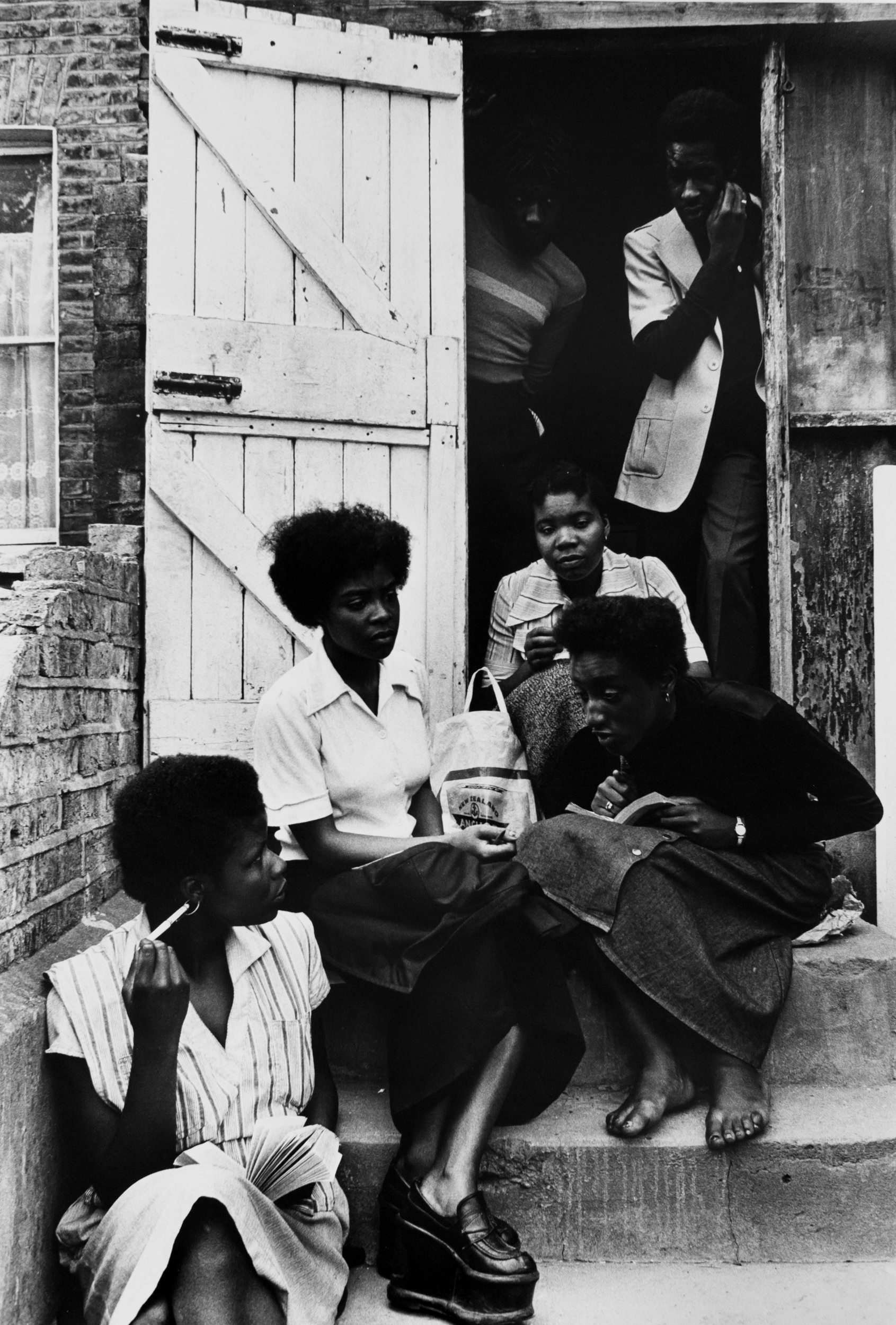

Colin Jones, The Black House, 1973-76. © Estate Colin Jones. Courtesy Michael Hoppen Gallery

The great British photojournalist Colin Jones passed away in September 2021 aged 85, occasioning a host of tributes that attest to his immense contribution to the medium as well as the lives he crossed.

Born in London’s East End and starting out as a ballet dancer (he bought his first camera on tour in Japan while running an errand for the ballerina Margot Fonteyn), Jones transitioned to photography in 1963. His documents of mining communities in the northeast and the high-octane hedonism of Swinging London have stood the test of time. But in an interview published on the Michael Hoppen website last year, he said that, of all his works, he was most proud of The Black House (1973-76).

“Could you do something on mugging?” the Sunday Times editor asked Jones and journalist Peter Gillman in 1973. It was a time when the British press had seized on the issue of “mugging” as a means of stirring up moral panic over Black criminality, in turn creating a distraction from the crisis of capitalism.

Jones and Gillman decided to focus their story on a hostel located at 571 Holloway Road. The brainchild of dynamic Caribbean migrant Herman Edwards, it served as a halfway house for vulnerable, disenfranchised Afro-Caribbean teens. Some had been thrown out by their families, while many had left school with no qualifications, finding themselves drifting in and out of the criminal-justice system. The refuge was officially called “Harambee” (Swahili for “pulling together”). But those who frequented it knew the place, rather contentiously, as “the Black House”.

“My camera in the house was very intrusive, so I wasn’t always able to use it as it could have provoked some situations to turn violent”

Before a photograph was taken or a word was penned, Jones and Gillman visited the Black House for months to gain the trust of the tight-knit group. There was understandable suspicion towards the two white outsiders. “Jones really stuck with it,” said Gillman. “He even corresponded regularly with one of them who had been sent to prison. With his gentle and beguiling manner, he was able to persuade the young men to let him photograph them.”

Jones never shied away from the complex nature of the relationship he shared with the residents. “My camera in the house was very intrusive, so I wasn’t always able to use it as it could have provoked some situations to turn violent. The problem is that I am white and these people, with all their problems, have very little to lose. Sometimes when I go through the front door, I can feel the pressure in the place.”

The resulting photographs illustrated the newspaper’s cover piece: On the Edge of the Ghetto (30 September 1973). But Jones was not the kind of photographer to shoot and leave. In the years that followed, he continued to pay his visits, sometimes with a camera and sometimes without. What followed was an expanded body of work that became not only a remarkable record of a vanishing place, but one of the most profound portraits of Black urban life in Seventies Britain.

“The Black House became one of the most controversial exhibitions of the decade, touring the country until it was vandalised in Leicester”

“They trusted no one,” said Jones. Yet his photographs, imbued with traces of proximity, belie his words. With his deep social conscience and eloquent photographic eye, Jones captured scenes of dignity, defiance and fraught beauty. In one photograph, it is winter and a woman leans against the hard wall, the flame of a jumped gas oven in the corner providing heat. While gender polarities are often pointed (the boys play cards in the half-light and the girls study on the steps), sometimes they all congregate in the backyard beneath the towering Victorian pile. Within each frame, we find humanity.

“I notice that a lot of boys are fascinated by the Black Power movement,” said Jones. “They also talk a lot about home, family, identity. That’s what [Edwards] is trying to do: help these young people to find and know themselves.”

That said, Edwards ultimately struggled to maintain a disciplined regime. The house was often in hot water, with neighbours reporting overcrowding or noise. Local subsidies expired, volunteers dried up and Edwards’s health deteriorated. Jones’ series concluded with the hostel’s closure in 1976. Regardless, Jones kept in contact with many residents, and was invited to photograph their weddings, funerals and other important occasions.

In 1977, The Black House was staged at The Photographers’ Gallery, London, and became one of the most controversial exhibitions of the decade, touring the country until it was vandalised in Leicester. For some, Jones had made heroes out of delinquents. For others, he conveyed a truth all too close to home.

“The hostel on Holloway Road served as a halfway house for vulnerable, disenfranchised Afro-Caribbean teens”

On the opening night, someone asked Jones: “In which part of America did you take these photographs?” He replied: “Holloway Road, about three miles from where we are both standing.” It was later that Jones realised: “It could have been anywhere in the world where a small community is threatened and afraid.”

Famously, one critic dubbed Jones the “George Orwell of photojournalism”. Yet looking back on his astounding lifetime, there is something rather limiting about the tag “photojournalist”. Jones was just a man who happened to find the means to say important things to those who took the trouble to care.

Alessandro Merola is assistant editor at 1000 Words