There aren’t many people who can say that their apartment has been reproduced in the name of art. But in 2018, a replica of the west London residence where Duggie Fields lived and worked for more than 50 years was painstakingly installed at The Modern Institute as part of Glasgow International, the biannual visual arts festival. If this sounds somewhat surreal, it is nothing out of the ordinary for an artist who led, by all accounts, an extraordinary life.

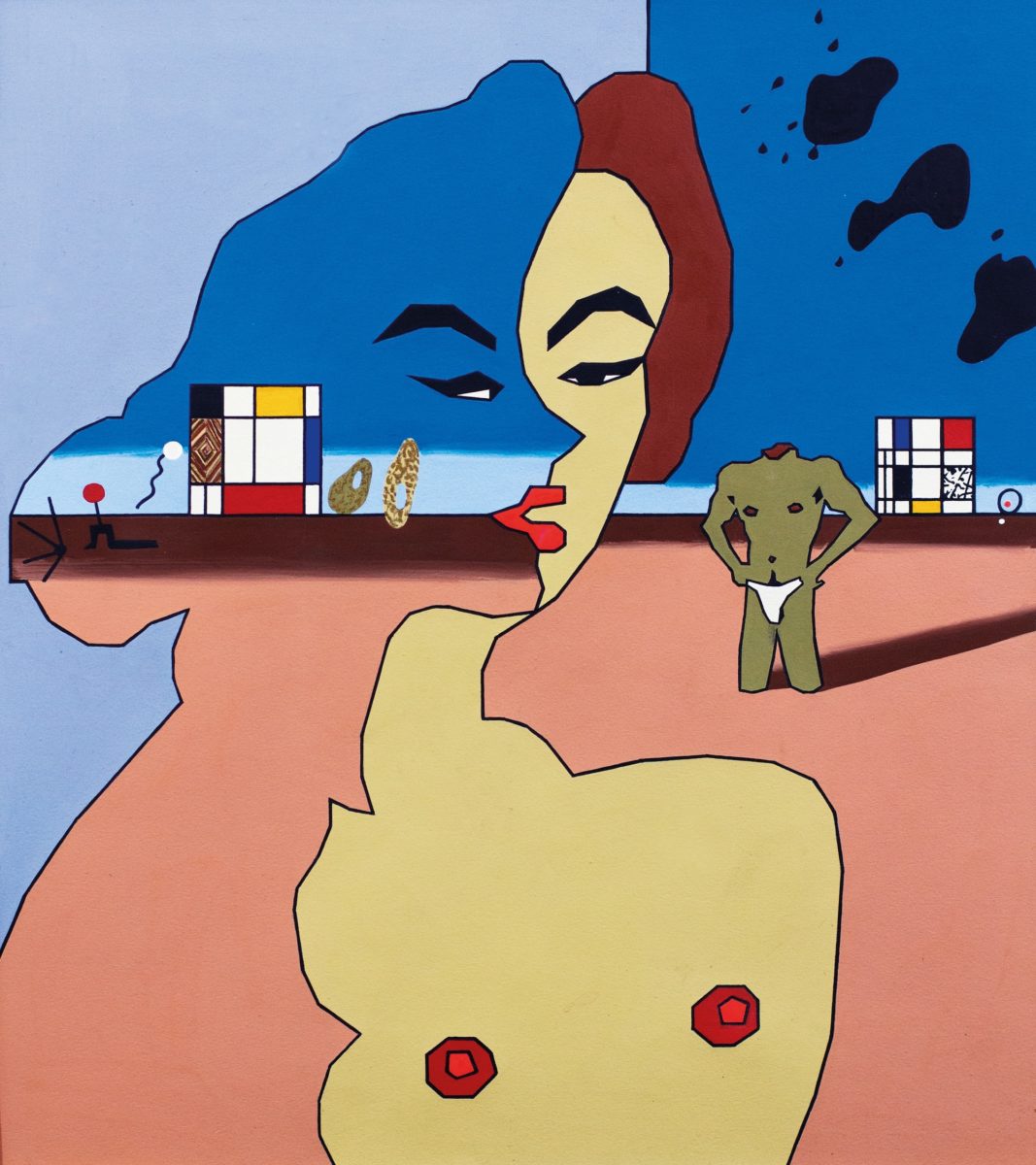

Fields emerged from Chelsea School of Art into the epicentre of the Swinging Sixties and the Chelsea Set; the apartment was rented on a whim with Syd Barrett, founding member of Pink Floyd. He quickly made a name for himself with his colourful paintings that infuse a Pop Art sensibility with a radically original way of seeing. His work combines art historical awareness with an almost cartoon-like use of bold outlines and flattened perspective. Broken statues and distorted female mannequins populate his paintings, set against bold, block colours that are as suggestive of Piet Mondrian as they are the graphic novelist Daniel Clowes.

“My parents had a pharmacy down the road from a clothes shop, which had mannequins. We used to hang out with the children of other shopkeepers,” he recalls. Fields’ parents’ store was decorated with cosmetics adverts, another important influence on his enduring aesthetic, which veers between the maximal and the unreal. Disembodied limbs whirl across some of his canvases; a single breast, complete with a perfectly round nipple, squats cheerfully at the centre of one composition. His outlook is playful and yet carefully considered, postmodern in tone but never overtly kitsch.

- Duggie Fields, Study for Joie de Vivre, 1978 (left). The bathroom of Duggie Fields' West London home, photographed by Louise Benson for Elephant (right)

Formerly a student of architecture (“All my paintings are about geometry”), Fields changed course when he found himself in the middle of a burgeoning creative scene that would go on to define much of the twentieth century’s counterculture. “I got a job in the record shop in Hampstead and started going to this jazz club behind Leicester Square. It was putting on rhythm and blues when soul music hadn’t really been discovered in the UK. This was in the early sixties, and they had this unknown covers band who were unsigned, called the Rolling Stones. So I saw the Stones with maybe 50 other people.”

“I don’t care for too much fame, but a little is fine. I don’t care for too much fortune, but a little is fine”

Fields quickly became embedded in the scene, living in Chelsea with members of Pink Floyd, who would rehearse at home. “The first tourists were just coming to London, and there was a parade of beautiful people, as we called them, on the King’s Road. There were visions on the street; amazing people came. Anyone interesting would come to the King’s Road,” he tells me. “Then I found this flat with Syd Barrett in Earls Court, and here I am 50 years later—I never expected that.”

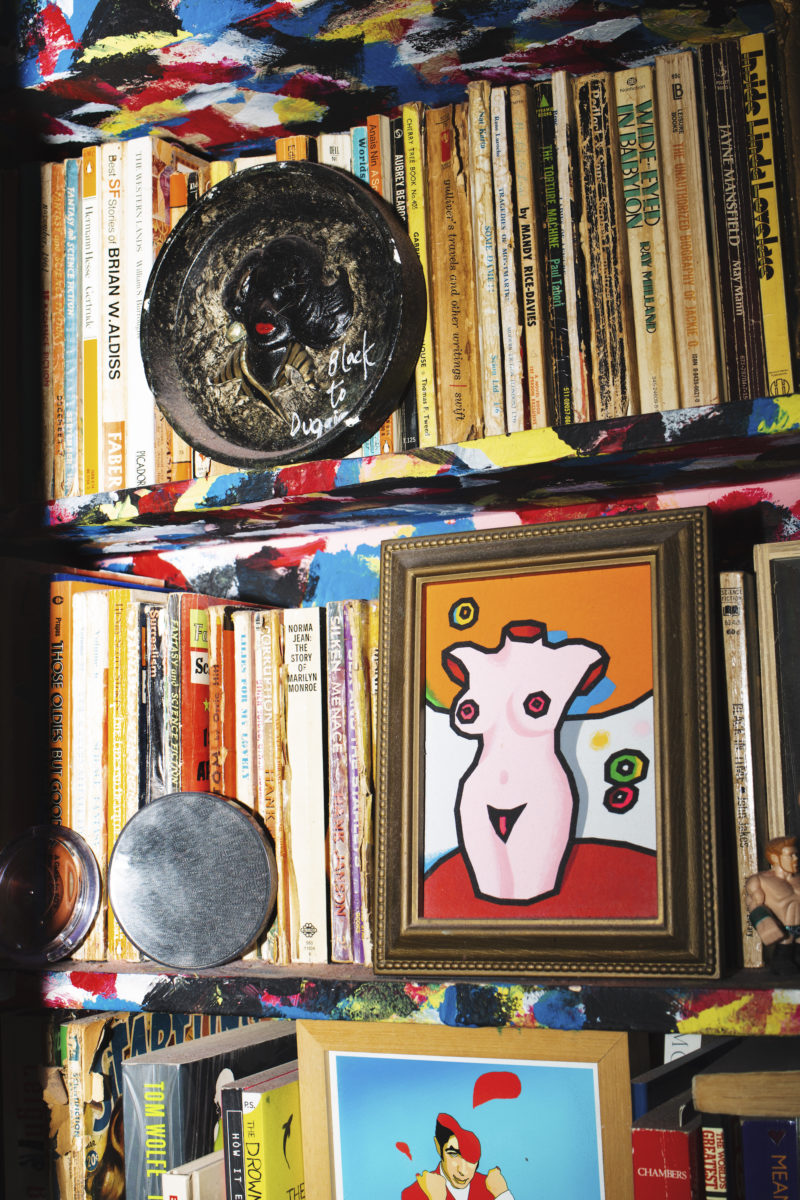

The layers of time can be deeply felt in the apartment, not only in the haphazard piles of books, magazines and assorted trinkets but in the architecture and design of the place. History is embedded in its very fabric. Black paint is flecked across linoleum floor tiles, and much of the furniture has been handmade by Fields over the years. Even the bathroom is crammed with books and novelty ornaments, and the walls daubed with rainbow paint.

“I don’t see any separation between my art and my life,” he asserts. “I live inside a painting. There used to be a mural here, and it was exactly like the paintings I was doing at the time, but without the figures. We became the figures inside.” It is a compelling image; looking around as Fields makes tea in the kitchen, it’s not difficult to imagine the people who must have passed through this space, like characters in an ever-changing theatrical play. The mural is gone now: “We had so many floods that the ceiling fell down. So the room evolved, as life evolves, and life is full of decay as much as anything else.”

“I’ve never actually been in the art world per se: I’ve always thought of myself as an outsider, and not unhappily”

Fields is speaking from direct personal experience, having recovered from cancer in 2019 shortly before his 75th birthday. He is unguardedly open about his illness, describing everything from the daily fatigue to the trauma of losing one’s hair after chemotherapy. For Fields, whose trademark quiff (his “forehead curl”, as he puts it) has been a defining signifier of his distinctive personal style for over 40 years, the loss was particularly devastating. “The whole way through being sick, I couldn’t physically paint,” he says, “but I could sit at the computer, so I’d be making films. I made collage films, mixing stills, drawings and random things I found.”

He describes a compulsion to create that has been with him since his teenage years. “I have a love of creativity and a love of making things. It’s a joyful thing to do, and I couldn’t live without it. I find holidays difficult.” Throughout his life he has eschewed the limelight for a quieter focus on creative work. “I don’t care for too much fame, but a little is fine. I don’t care for too much fortune, but a little is fine. A little more of both would be very nice,” he says, candidly, “but a little more than that would actually disturb my life too much. I paint best when the studio doors are closed and there’s no one around.”

He is quick to recount the cautionary tales of friends who had big fame thrust on them in the 1970s—“both dead now. Both turned upside down from it. One fled into himself. The other fled into drink and drugs.” You have to keep yourself in check, he intones, as he warns of people’s egos being taken by the glamour and demands of it all. “I’ve never actually been in the art world per se,” he argues with a smile. “I have always thought of myself as an outsider, and not unhappily. I remember, when I was a student, we weren’t supposed to want to be in museums or to admire them. We were supposed to be anti-bourgeois and bohemian.”

Fields has long resisted what some would consider the natural trajectory, choosing instead to resolutely take his own route. He shows me a drawing that he completed for Stanley Kubrick, commissioned by the filmmaker for the poster to accompany the upcoming release of A Clockwork Orange in 1971, adapted from the novel by Anthony Burgess. “I read the book when it was new, earlier in the sixties,” Fields remembers. “And then, when he asked me, I read the book again. I got a very strong vision of the film of the book, but it wasn’t Kubrick’s film.”

- Duggie Fields, SMart, 1976 (left). Duggie Fields, Study for Sheer Obscuro, 1975 (right)

Rather than follow the strict brief, Fields painted a head floating on an abstract background, a move towards the more figurative work with which he has since made a name for himself. “He liked the painting, but it didn’t become the poster because I didn’t do what he wanted. He used it as a trailer in the cinema, and he also made it into an iron-on transfer and a limited-edition sweater.”

“I don’t see any separation between my art and my life. I live inside a painting”

Fields was then invited to watch the film at Kubrick’s own home, played on a hand-cranked Moviola turned frame by frame, in order to create a new artwork from it. “I came away with lots of stills. I spent a couple of weeks, and then I said no. He was offering me more money than I’d ever earned in my life. But there was no image there for me. I would have had to compromise too much.”

Fields continues to maintain a unique and unwavering vision. He paints daily, and creates music and film on his computer, all of which share a frenetic pace and inherent curiosity about the world around him. His visual style has remained remarkably consistent over the years, revealing a prescient state of mind from the early 1960s which still resonates today. In his flat, canvases are stacked against the wall, up to ten deep. “It’s an odd experience being in the same place for so long,” he reflects, “because I feel in some ways that I’ve travelled through time. The place is the same but the time has changed.”

He remains embedded in the heart of London, taking pleasure in the life of the city. He regularly strolls through the nearby Brompton Cemetery, filled with the changing colours of wildflowers that have sprung up amongst statues and headstones showing the signs of two centuries of weather erosion. Fields has almost completed a large-scale painting of the cemetery, all graphic outlines and acid green foliage. He is busy sketching out new works, with acrylic paints already mixed to one side.

As our conversation draws to a close, I can almost feel him itching to resume work, and to close the studio door once more. “If I had died last year, and I nearly did, I wouldn’t have thought, ‘Oh, God, I missed out,’” he concludes. “I would have had no regrets whatsoever.”

In memory of Duggie Fields (1945 – 2021)