It feels pretty poignant that just over a week after the announcement that the book Genesis Breyer P-Orridge: Sacred Intent was to be published (timed to mark P-Orridge’s seventieth birthday on 22 February) came the announcement of their death on 14 March. Though, in some senses, it also seems partly fitting—the old “what they would have wanted” cliché. The artist, musician, pandrogeny pioneer and cultural provocateur led a life in which things rarely were explained by simple coincidence.

The book brings together three decades of conversations between Genesis P-Orridge and Swedish author (and Trapart publisher) Carl Abrahamsson, and demonstrates beyond doubt the artist’s unique knack for wringing symbolism and meaning from events, meetings, ideas and sounds that others would miss. P-Orridge formed a life and practice from reassembling the broken fragments, that make up a life, a song or an image, into entirely new entities.

Such reassembly of broken pieces calls to mind the cut-up techniques revered by artists like Brion Gysin and William Burroughs. It is emblematic of the belief that the union of two separate entities to create a third new one—be that in a collage image, a sound piece, or indeed a relationship or gender identity (as with P-Orridge and Jacqueline “Lady Jaye” Breyer’s pandrogeny project, as documented in The Ballad of Genesis and Lady Jaye by Marie Losier)—can be applied to life and death, perhaps, as much as art. That is, if we separate life and art, something it seems P-Orridge was unwilling or unable to do. Indeed, the art and music collective COUM Transmissions that s/he co-founded was a staunch proponent of art’s purpose in society being, quite simply, “art as life”.

“It demonstrates beyond doubt the artist’s unique knack for wringing symbolism and meaning from sounds that others would miss”

Perhaps the coincidence of the birthday and the death of a cultural icon colliding was the ultimate conclusion of the book’s title: the “sacred intent” that underscored P-Orridge’s foundational respect for a patchwork of spiritual and “magickal” worldviews. As the artist stated in a 1988 interview published in the book, quoting Burroughs, “People think that all they have to do to write a good novel is to do a cut-up. But the skill is knowing what to cut up and how much to cut up and where to put each section.”

For those unfamiliar with P-Orridge, s/he founded the music and performance art project COUM Transmissions in 1969, which unexpectedly hit tabloid headlines in ways few such esoteric, experimental or extreme practices have. This was thanks to its inclusion in the Prostitution exhibition at the ICA in 1976, which showcased musician and COUM cofounder Cosey Fanni Tutti’s pornographic work, including a glass-encased used tampons, syringes, rusty knives and other shocking artefacts. It was enough for Tory MP Nicholas Fairbairn to brand them the “wreckers of Western civilization”. When the press caught on, COUM cut up reviews of their show and displayed them.

P-Orridge went on to found the seminal band Throbbing Gristle, in which Chris Carter’s electronics and synth wizardry shone through as a pillar that brought P-Orridge’s more outlandish ideas into a terrifying sonic realm. Peter “Sleazy” Christopherson and Cosey’s influence, too, on the band’s sound is not to be underestimated. P-Orridge’s subsequent project, Psychic TV (and its various incarnations as PTV3), never quite packed the same punch.

P-Orridge leaves behind a complicated legacy, with difficult issues that resist outright praise of their life and work. Like countless people, my views on P-Orridge were forced to shift when I read Cosey Fanni Tutti’s memoir Art Sex Music, which details the abuse she faced, including physical attacks (such as P-Orridge throwing a breeze block from a balcony to landed near her head), pressurising her into unprotected sex, taking credit for her work and more.

In the 1990s, P-Orridge moved to the US following damaging false allegations made in a Channel 4 Dispatches documentary that s/he had been involved in satanic ritual abuse. P-Orridge, it must be said, denied all claims made by Cosey and others though many, many people who worked with them attest to their dominance and “ability to manipulate others”. As it’s put in a Guardian piece, Genesis P-Orridge: fantastic transgressor or sadistic aggressor?

None of these things, however, negate the fact that P-Orridge’s contribution to music and art changed the landscape forever. But they do muddy the waters for books like this, which are based on conversations between two friends, over a period of more than thirty years. It’s a tricky thing to navigate (as articulated by our own Charlotte Jansen), which Luke Turner summed up beautifully in his obituary on The Quietus: “I do not believe that their abusive behaviour means we shouldn’t listen to the music of Throbbing Gristle—to do so would be unfair on the three other members… Have any icons you care to follow, experience whatever art you choose, but at least acknowledge the truths of the lives of those who made it.”

“P-Orridge leaves behind a complicated legacy, with difficult issues that resist outright praise of their life and work”

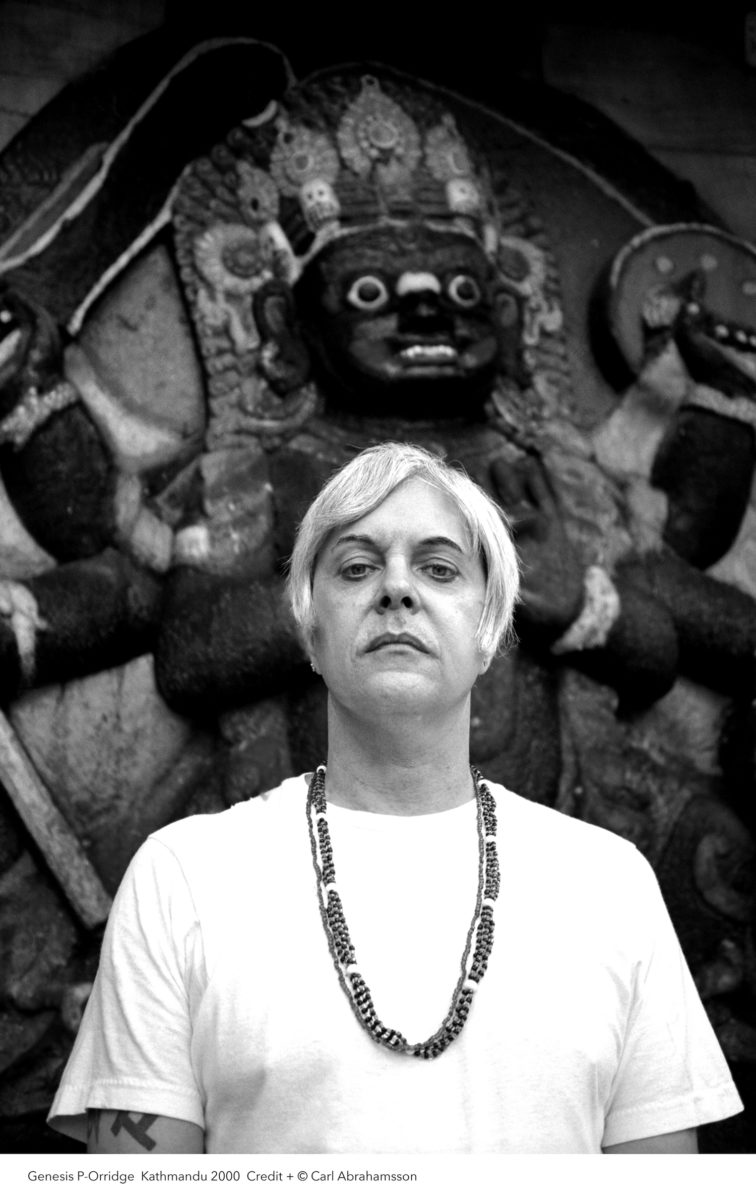

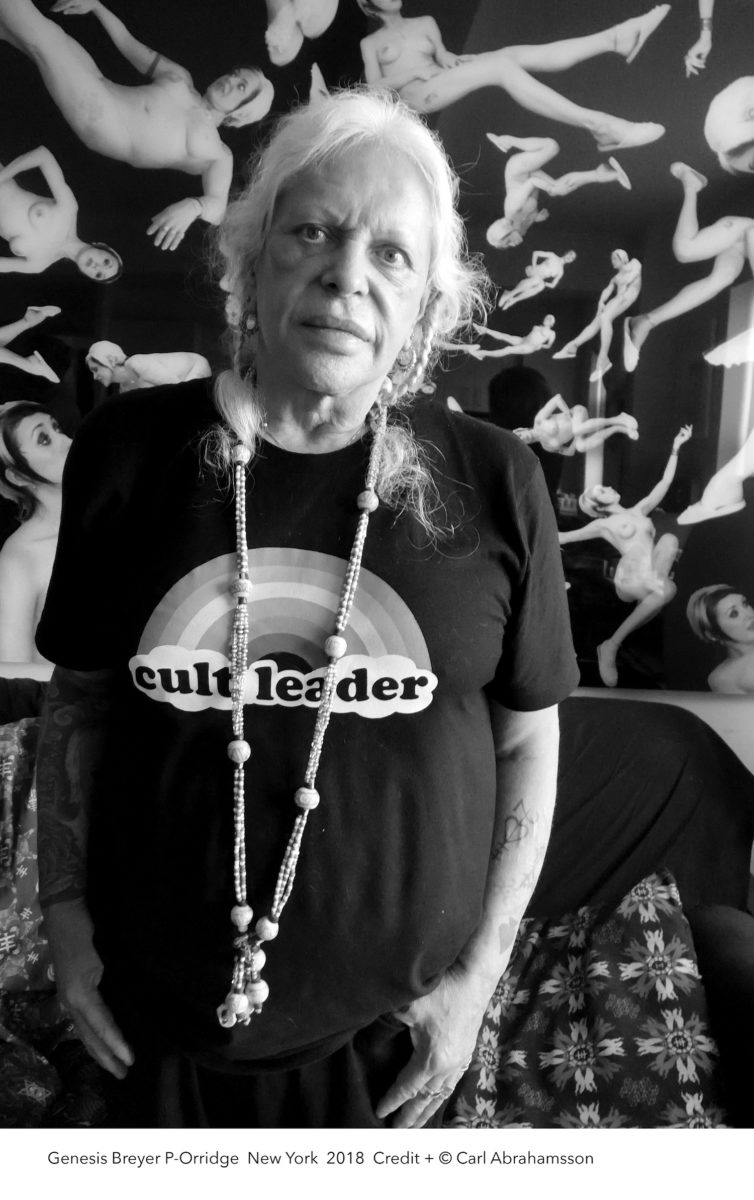

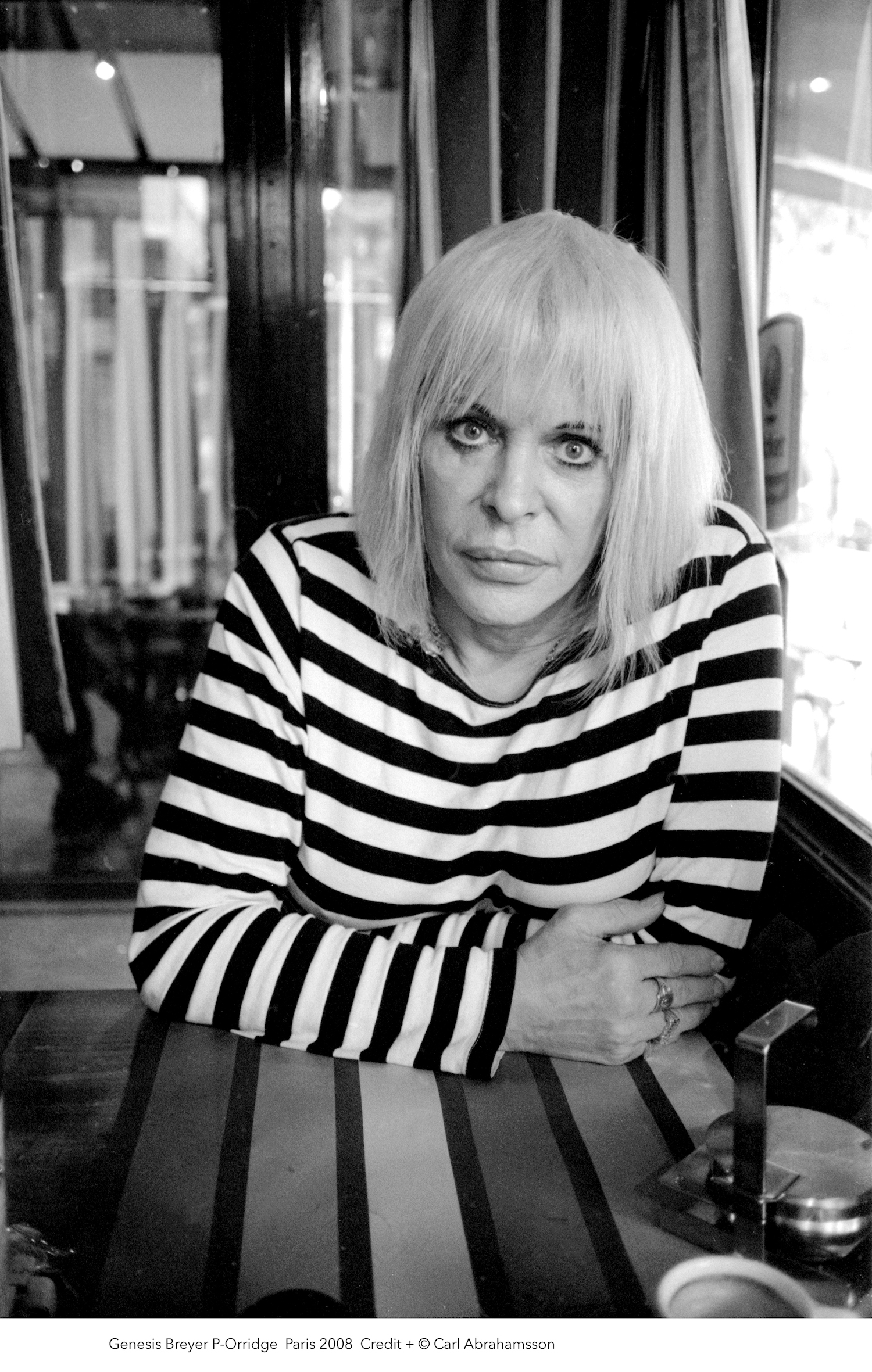

In Abrahamsson’s Sacred Intent, we see this truth through the lens both figuratively and literally. The conversations between the pair are illustrated with portraits shot by Abrahamsson of P-Orridge and Lady Jaye, along with interviews dating back from the pair’s first meeting in 1986, when Abrahamsson spoke to P-Orridge for his fanzine. Afterwards, he says “nothing was quite the same. I not only respected P-Orridge as an artist and ‘conversationalist’ even more, but had also come to the insight that what TOPY was doing was simply so unheard of and ‘new’ that I definitely wanted to be a part of it.”

In 1988, he revisited London to interview P-Orridge again, and the pair developed a friendship that lasted for the rest of the artist’s life and took in not only interviews, but collaborations across various music and art projects and meetings across the world, including a trip to Kathmandu, Nepal, in 2000.

The conversations really do, as you might expect with more than thirty years’ worth of chatter with P-Orridge, cover a hell of a lot of ground. There are barely any parts of the interview transcripts that deal with trifling matters or trivialities. Instead, the world is articulated through any number of often complex viewpoints: the impact of drugs like ecstasy and ketamine as partial agents of human evolution; grumbles about the “hypocrisy” of the formal art world, which P-Orridge saw as run by “people [who] didn’t really believe in art at all; they believed in business”; P-Orridge’s inability to separate life and art; what it means for us to take ownership of our physical bodies.

“P-Orridge has a superb knack for translating the hard-to-comprehend into beautifully succinct snapshots of meaning”

Everything is considered in these conversations—all the threads are woven together with a conviction and profundity that draws from both the knowledge of two very well-read people, who clearly do a hell of a lot of thinking, and from a spiritual standpoint that vacillates with the years. P-Orridge has a superb knack for translating the hard-to-comprehend into beautifully succinct snapshots of meaning. Certain phrases leap off the page and smack you right in heart: “It seemed almost too ridiculous that all my life I’d been trying to understand the universe when in fact it already understood me,” says P-Orridge, discussing a reading in Kathmandu to determine their Orisha spirit. “I just hadn’t got the information.”

Whatever your views on P-Orridge, there’s no denying that their ability to articulate the deepest, most complex riddles of life and love was a very rare talent. They hit upon truths of the soul and the strange currents that underpin the physical, explainable world better in startling, revelatory ways that are at times uncomfortable in their accuracy. At other moments, they are almost soppy or saccharine in their forthright telling of what it is to be alive and in love. This extends into the metaphysical: the idea of the soul as our true being, not, as P-Orridge often quoted from Lady Jaye, the “cheap suitcase” that is our physical body. “The body is not sacred,” s/he’s said. “It carries around the real you, which is your consciousness, your mind, your thoughts, your aspirations and dreams.”

Genesis Breyer P-Orridge: Sacred Intent. Conversations with Carl Abrahamsson 1986–2019

Published by Trapart

VISIT WEBSITE