Image: Mohamed Somji.

Driving into Dubai at 9am, everything is glitter and mirrors. Post-modern monoliths of blue, beige and gold tinted glass reflect each other reflecting the morning light. Highways wind in and out of glinting construction sites, buildings built to be seen in motion. The skyline has been going up here since 1979, when the first skyscraper, Sheikh Rashid Tower (now Dubai World Trade Centre), was erected as a space for holding trade exhibitions and events. Now this tower sits as a baby watched over by hundreds of high-rises, which are in turn watched over by the sharp point of the 828-metre-high Burj Khalifa.

I am here on my first visit to the UAE, and my first press trip, to see Alserkal Avenue, Dubai’s self-proclaimed “foremost arts hub”; a compound of warehouses built specifically as spaces for art galleries and creative initiatives ten years ago on land owned by the Alserkal family. Since the first gallery, Ayyam, moved in in 2008, the complex has grown to what Abdelmonem Alserkal and the director of The Avenue, Vilma, describes as a “curated community”, receiving an extension to double its size in 2012. Of the ninety warehouse spaces, sixty have been filled with concepts, which range from galleries focusing specifically on Middle Eastern art such as The Third Line, to larger galleries like New York’s Leiler Heller, and cafes and spaces used specifically for pop-ups, one of which is hosting Photo Riahi during my visit, a project by Bahman Kiarostami about a photography studio in Lavasan where workers would get portraits of themselves photoshopped onto paradise-like backgrounds to send back to their families, another, a piercing pop-up from California.

In the industrial district of Al Quoz where the Avenue is located, the buildings are low and wide, a far cry from the glitzy glass and metal beach hotels of Jumeirah and the screen-heavy Dubai Mall teeming with western tourists. It is home to some brilliant galleries, such as Green Art, which has a four-decade-long history of activity in the Middle East, beginning life as Ornina in 1987 in Syria, and which is showing Theatre of the Absurd, an exhibition that looks at the relationship between art and architecture. Ana Mazzei’s richly-coloured sculptural installation sits alongside elegant works on paper, which have a slight resemblance of architectural plans, by Elena Alonso.

Image: Musthafa Aboobacker

Gulf Photo Plus is also a highlight, with an exhibition of work from photographer Aida Muluneh, The Memory of Hope. Her primary-coloured compositions explore the erosion of the naive and simple understandings we have of right and wrong when we are young.

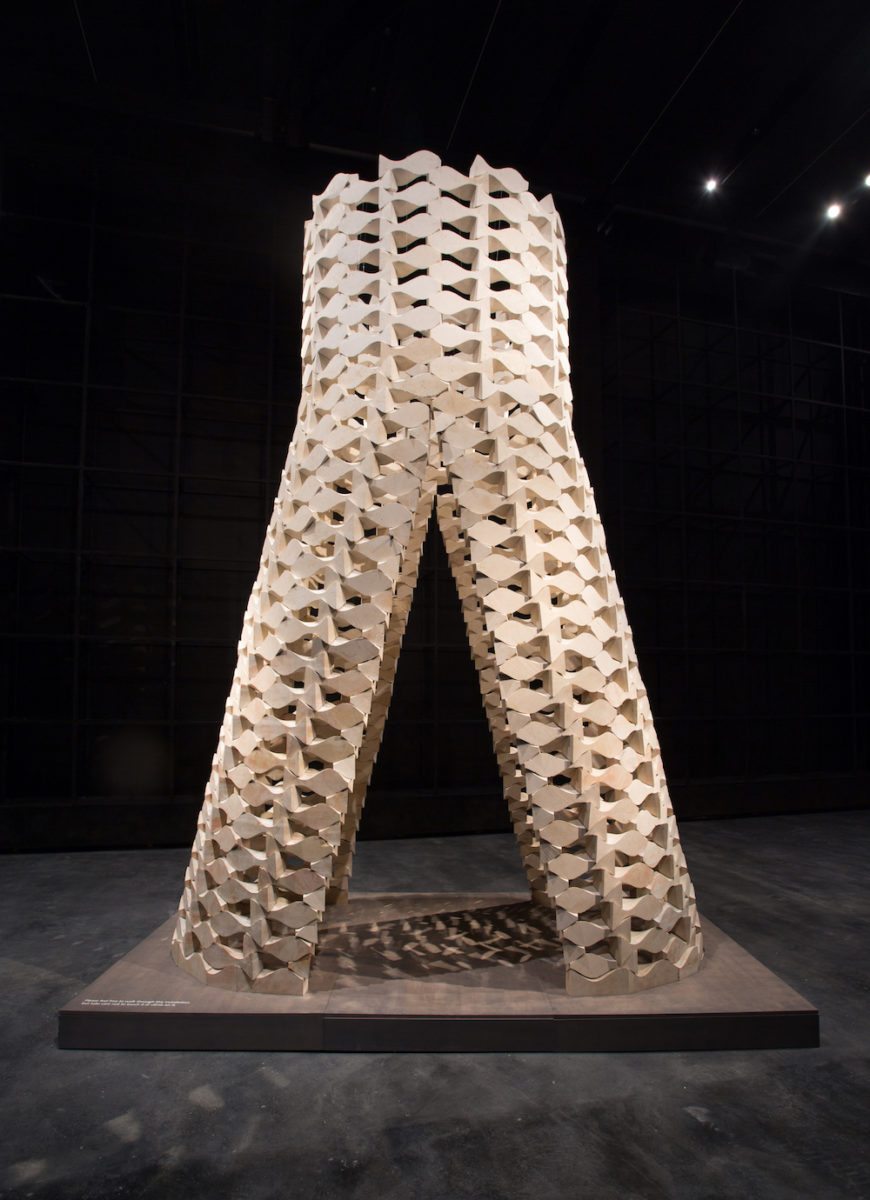

Yet the current star of the Avenue is the new Rem Koolhaas-designed Concrete. With a gritty finish of sprayed concrete embedded with shards of mirror, the building twinkles against the blue sky like a rock formation from Mars. Slipping through the black-curtained door that is situated on the side of the building, visitors are greeted with an enormous dark space, cool and quiet, cut in half by a floor-to-ceiling projection screen. It is displaying a meditative split screen video by artist Mikaela Burstow, showing the rich imagery of the Cremisan Valley in Palestine, the inspiration behind Palestinian artists and architects Elias and Yousef Anastas’s exhibition While We Wait. This is a project about the relationship between man and nature, and, specifically, about the “cultural claim” over nature, as a separation wall is being built that threatens to cut through the valley and deeply disturb the natural landscape there. Behind the screen, however, hides the centrepiece of the Anastas brothers’ work: a stone structure consisting of six hundred pieces of limestone, all robotically carved and then finished by hand, built by an algorithm to fit together and stand independently without cement or mortar, a technique they call “stereotomy”. This is a structure that has travelled: initially being set up in London’s V&A museum, now in the cool darkness of concrete, and next back into the Cremisan Valley, where the Anastas’s will re-build the structure one last time and wait for nature to take its course.

- While We Wait

Image: Musthafa Aboobacker

Taking a rest from the gallery tour in a café serving cold-pressed juices and kale chips, I can’t help but be reminded of London’s gentrified Shoreditch in the numerous pop-up stores, coffee shops and workspaces on the Avenue.

For dinner we travel to Bur Dubai, one of the historic regions of the city, a busy residential area full of apartments and shop fronts with bright neon signage and lives happening. It feels as if we’ve slipped through a crack in the pristine glass of the newer areas. We eat at the Persian kebab restaurant Special Ostadi, whose wood-panelled walls are adorned with thousands of photographs and framed early 2000s mobile phones and cameras, and whose air is filled with the surprisingly loud song of a tiny yellow budgie in a cage above a shelving unit. In the Uber journey there my ears are caught between art world controversy in the back seat and an explanation of Bur Dubai’s history from the driver, whose name I wish I had taken but didn’t, in the front. He explains about the public park along the Dubai Creek that is being closed off by a big development and real estate company, and the lack of care from these companies for what he said Dubai’s culture was supposed to be. We drive past an enormous sign for Dubai Garden Glow, technicolour dolphin light sculptures peeking out from behind. “They don’t like the grass,” he says, “because it gets to stay there for free.”

Image: Musthafa Aboobacker

The next day we travel to the emirate of Sharjah to visit the government-funded, coral-walled Sharjah Art Foundation, which is currently hosting an enormous retrospective of Hassan Sharif, the prolific Emirati artist often credited as the father of modern art in the Emirates. Full of energy and humour and without an air of preciousness, Sharif’s work flits from geometric abstraction to performance; in this show there is a huge pile of flip-flops in the middle of the gallery floor. Perhaps at times it is a little too comprehensive. Documentations of his performance works are a highlight as they outline in detail the inane tasks he would make an audience sit through. One such example: “Some parts of the library there were shelves with books, on the other parts there were shelves without books and on the other side there weren’t even shelves. During the performance I explain to the audience a few useless reasons about the library situation.”

On our last morning, we finally visit the long-awaited Louvre Abu Dhabi. Designed by Jean Nouvel, the building is, of course, stunning (and there are more nudes in the collection than you might expect!). Here I bump into Suvji, our tour guide from the previous day’s tour of Abu Dhabi Art Fair, rushing around the museum with two of her friends. A student at the Paris Sorbonne University in Abu Dhabi, she is excited by the fact that the curation “bridges the gaps between civilizations”, adding that she almost cried at the statue of Athena. She is so unreservedly enthusiastic about the museum that it rubs off.

But even strolling the main hall, where the roof spills dappled light across the enormous commissioned Jenny Holzer wall piece and you can hear the almost unbelievably blue sea lapping at the building’s facades, the well-documented accusations that this structure, like many others on Saadiyat Island (and indeed across the UAE), including the new Guggenheim, was built largely by migrant labourers living in labour camps under extremely poor conditions cannot be set aside.

- Concrete, designed by Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA), Exterior Detail. Image: Mohamed Somji

That afternoon we take a trip to the silencingly opulent and surprisingly serene Abu Dhabi Grand Mosque, and then to the Dubai Mall. Streams of people mill through the open doors of the Apple store and a seemingly unflinching crowd stand by to watch the fountains from the balcony. There is a sweet shop where you can get your face printed in 3D gummy sweets. There is a Christmas-themed window with life-sized animated child dolls, in a shop named Irony Home. There is an aquarium populated with stingrays and sharks. We spend a good deal of time looking through the large number of jewellery displays and picking out which piece we’d buy from each window if we had the money. The lights of the Burj Khalifa twinkle, or rather fizz on and off erratically. I get some kind of reverse vertigo from standing at its foot.

All images courtesy Alserkal Avenue