Elephant and Artsy have come together to present This Artwork Changed My Life, a creative collaboration that shares the stories of life-changing encounters with art. A new piece will be published every two weeks on both Elephant and Artsy. Together, our publications want to celebrate the personal and transformative power of art.

Out today on Artsy is Sophie Haigney on René Magritte’s Pandora’s Box.

In Pretty Baby, Louis Malle’s piquant 1978 film about a twelve-year-old prostitute, a madam auctions off the girl’s virginity, the setup hardly different from a sale at Sotheby’s in its emphasis of her rarity, her quality and her extraordinary value. She is dressed in white to underscore her innocence, and she is made up like a doll; her name is Violet, as in “shrinking,” and the actress playing her is an extremely young Brooke Shields

, who looks exquisite in repose, but moves and talks in such a way that it is obvious she’s a child. Five or six middle-aged men, none of them shy about expressing their desire for a prepubescent girl, start placing bids. It is 1917 in New Orleans, and war is raging on four continents, making both youth and innocence more valuable fetish commodities than ever. “You can look all you like,” the madam creaks, a note of hunger in her voice, “just don’t break the merchandise.” The scene, to me, feels like a perfect metaphor for the onset of puberty in pre-teen girls.

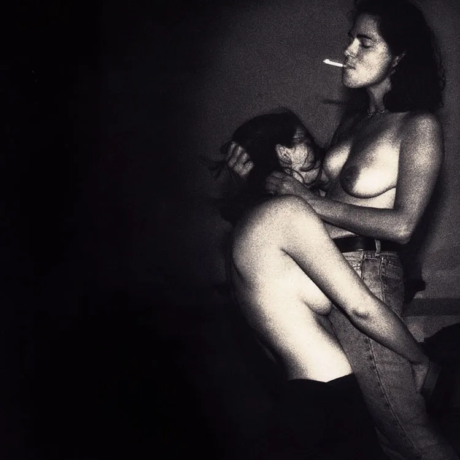

In 2009, a photograph of Brooke Shields, taken in the same year she made Pretty Baby, was removed from display in the Tate Modern. It was seized on the grounds that Shields was naked, made up to look like an adult, and posed in a way that made the image look like child pornography. Evidently, looking all we liked was no longer permitted. I was twenty-one that year, an art school student with an art school student’s love of the transgressive, and the piece—Richard Prince’s Spiritual America, itself a photograph of an original image by the relatively unknown Gary Gross—had fascinated me since I was maybe fourteen or fifteen, when I saw it for the first time.

I don’t remember whether I was first exposed to it online, or in a book of modern art. I do remember the extraordinary feeling of unearthing it when I was underage myself—a sudden forced acknowledgement of certain truths about the way men looked at girls, and by extension, of the way that certain kinds of men prized youth over experience. It struck me in particular that the hysteria that surrounded Spiritual America

had been opprobrium, yes, but it had also been excitement. I recall being scandalized to learn that the original shot had been commissioned by Shields’ mother, and that she had signed the rights over to Gross and to his partners, Playboy Press, for the insulting sum of $450. I remember, too, a realization that, however young I was, I would not remain young forever. I would very soon be legal, and then I would be a woman, and then someday I would be so very old—like, thirty-five, or even forty—that in some ways it would barely matter, sexually-speaking, whether I continued to exist at all.

“I remember unearthing the image when I was underage myself—a sudden acknowledgement of certain truths about the way men looked at girls”

“[Shields] has a body with two different sexes, maybe more,” Prince had said about the image, adding that her head “looks like it’s got a different birthday.” What he meant was that her body, prepubescent to the point of being unidentifiable as masculine or feminine, appeared below a face that more or less already looked like Brooke Shields’ face, the end result more “alien” than “pretty baby.” He had come up with the title after visiting the Met one afternoon and discovering a photograph of a horse by Alfred Stieglitz with the same name; a close-crop of its hind quarters showing that it had been gelded, the stark combination of its musculature and its lack of genitals reminded him of Shields’ lean, pre-sexual beauty.”

To be pre-sexual is, under normal circumstances, to be unaware of the male gaze, a state of innocence that lasts until somewhere between a girl’s first training bra and her first period. By the time I reached my teens, I was aware of the effect that teenage girls—developed enough to look physically like almost-women, insecure enough to seem like easy prey—had on the kind of adult men who catcalled. These were the same men who followed schoolgirls home to try and press phone numbers into their small palms, or who were only ever turned off by the mention of a boyfriend.

“Go ahead, look all you like,” young girls get used to thinking to themselves, a petty compromise in lieu of violence, “just don’t break the merchandise.” It had not occurred to me that all the time I had spent unconcerned about being looked at had not necessarily precluded me from becoming an object of some secret fascination. The shot used for Spiritual America, a judge ruled in a court case between Gary Gross and Teri Shields, had “no erotic appeal, except to possibly perverse minds.” But how many perverse minds had I unknowingly encountered? And hadn’t the same judge also said the picture had a “sultry, sensual” appeal?

“To be pre-sexual is, under normal circumstances, to be unaware of the male gaze”

Stieglitz saw the gelded horse as a representation of America, physically powerful but spiritually neutered. Prince saw Shields, her pose a little reminiscent of the crucifixion, as the embodiment of a new cultural and sexual religion that saw youth as paramount, a force more potent and desirable than God. In 1978, the year Gross shot the fateful picture, CK Jeans were using Patti Hansen—a blonde Staten Island model for whom Esquire magazine rang in “the year of the lusty woman”—as the face of their campaigns. By the early 1980s, they had moved on to fifteen-year-old Brooke Shields: Dolores on the dotted line, Lolita in her Calvin Kleins. “Nothing,” she suggested, “gets between me and my Calvins.”

Klein himself admitted that he thought of “buxom” women’s bodies as unruly, “vulgar,” and too glamorous, a hot distraction from the minimalist chill of his aesthetic. “A lot of [models],” he said in 2011, “were having implants in their breasts, they were doing things to their buttocks. It was getting out of control. And I just found something so distasteful about all that and I wanted someone who was natural, [and] always thin.” In Spiritual America, the preteen Shields’ flat chest and small, epicene hips do not look far removed from the flat chests and small, epicene hips of most contemporary clotheshorses. Shields is Schrödinger’s model: illegally young, and fashionably devoid of the signifiers of adulthood that make women “vulgar,” “buxom,” and too fully-grown for alteration. That her body was not shocking to a teen girl who read fashion magazines was, in itself, one of the most disturbing things about the image.

“Shields is Schrödinger’s model: illegally young, and fashionably devoid of the signifiers of adulthood that make women ‘vulgar’ and ‘buxom’”

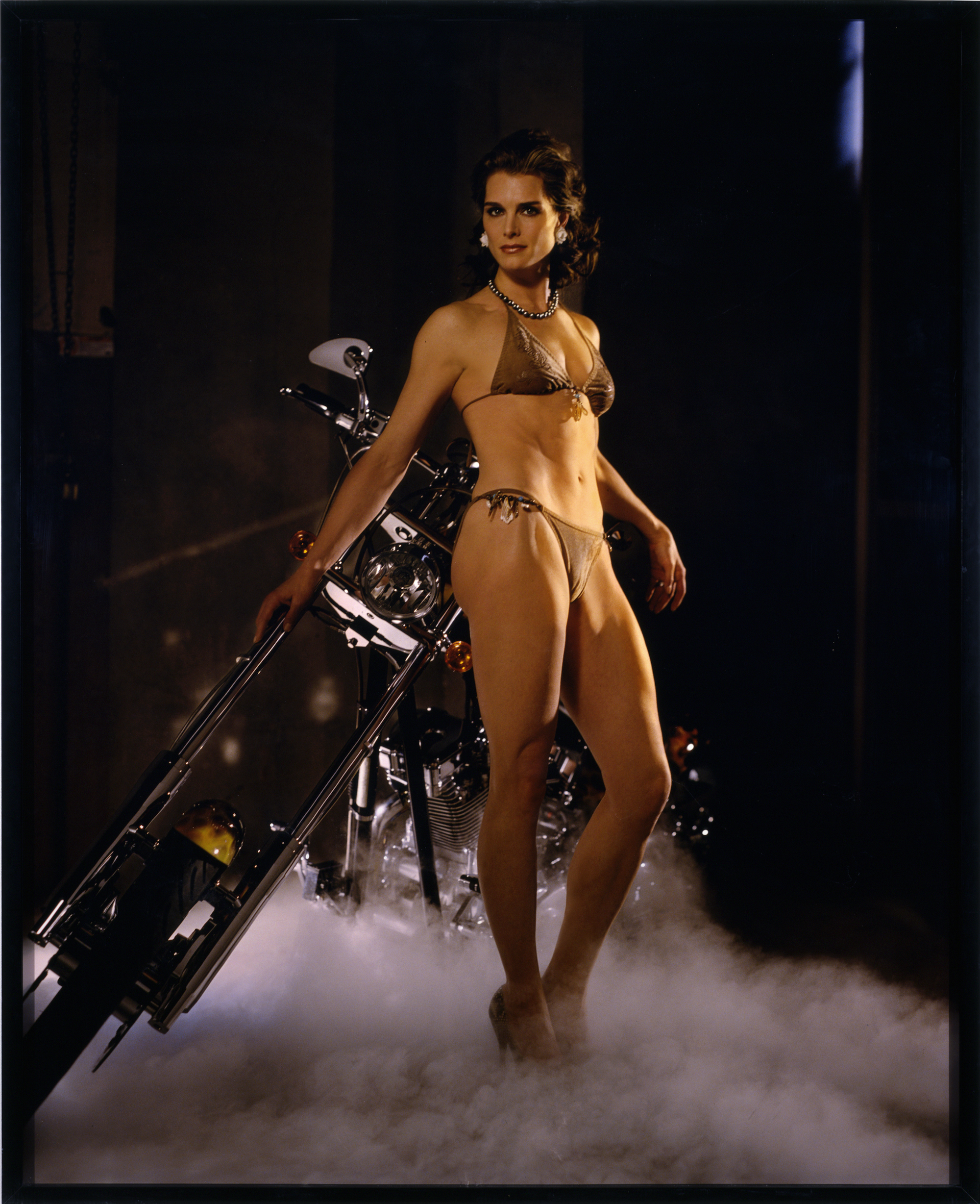

Now I am thirty-two years old, making me more than twice the age I was when I discovered Spiritual America, and roughly ten years older than the woman many, many men are looking for on OKCupid. I am also eight years younger than Brooke Shields was when she sat for Richard Prince for the follow-up to Spiritual America in 2005. Dressed in a coffee-brown bikini, leaning on a motorcycle, the adult Shields no longer looks serious or contemplative, but amused—her body is no longer epicene or alien, but hyperfeminine, a mudflap girl’s. She had by this point had a daughter, and would give birth to one more the following year.

The photograph must have been taken two or three years after my encounter with the original work, and yet I have no memory of seeing it until my student years, in 2009, when Spiritual America was seized, and newspapers needed an image they could print. I do recall, extremely vividly, reading an interview with Brooke Shields about how long she had waited to have sex—how she had lost her virginity at the age of twenty-two because of how terrible her earliest experiences of being sexualized had made her feel about her image.

The impression Spiritual America had made on me in my mid-teens, prompting a realisation that youth was and always would be the most dazzling quality a girl could have for certain men, was underscored by this new image. A powerful reassessment of the subject, through which Prince cleverly deepens the sinister poignancy of the original, it nevertheless took a story about its much younger sister for the shot to make the papers. At a sale in 2014, an edition of Spiritual America (one of ten, “from a private New York collection”) sold for $ 3,973,000 at Christies. The remake, auctioned at Phillips, fetched about one tenth as much. “The tighter they are,” as a spokesman from Calvin Klein said in the eighties, ostensibly on the subject of their jeans, “the better they sell.”

Did an artwork change your life?

Artsy and Elephant are looking for new and experienced writers alike to share their own essays about one specific work of art that had a personal impact. If you’d like to contribute, send a 100-word synopsis of your story to office@elephant.art with the subject line “This Artwork Changed My Life.”

Head to Artsy to read their latest story in the series, a piece on René Magritte’s Pandora’s Box

READ NOW