We currently find ourselves in the age of the celebrity curator, in which figures like Klaus Biesenbach and Hans-Ulrich Obrist have well and truly infiltrated pop culture. There are key figures who transformed the curator archetype from that of a stuffy, tweed-wearing museum nerd to a glamorous mover and shaker, whose prominence is on par with the artists they champion. Swiss curator Harald Szeemann is an exemplary forebear to this new breed. In the post-war era, he transformed the role of curator from that of an object arranger to an independent tastemaker. As the creative force behind a slew of biennials and other encyclopedic shows, Szeemann’s ambitions took art from the white walls of museums into the open arena of the world stage.

“As a creative for hire, Szeemann tilled the field in which all amorphous, self-employed creative freelancers now exist”

Born in the capital city of Bern, Switzerland, Szemmann came into the art world via a meandering route. He tried on a number of hats during his youth, moving between acting, set design and painting. Eventually he settled on curating, beginning his career at the Kunstmuseum St. Gallen and going on to establish himself at Kunsthalle Bern. At the Kunsthalle Bern, Szeemann mounted radical presentations such as Bildnerei der Geisteskranken – Art Brut – Insania Pingens (Art of the Mentally IlI) in 1963, combining the work of pioneering avant-garde figures with art made by patients of a mental health facility. In 1969, after serving as the Kunsthalle’s director for eight years, Szeemann headed down a rather untrodden path, becoming an “independent curator”. He marketed his new mission under the auspice Agentur für Geistige Gastarbeit (Agency for Spiritual Guest Labour) and even went to the lengths of designing his own stamps and packing tape (curators need marketing too). As a creative for hire, Szeemann tilled the field in which all amorphous, self-employed creative freelancers now exist.

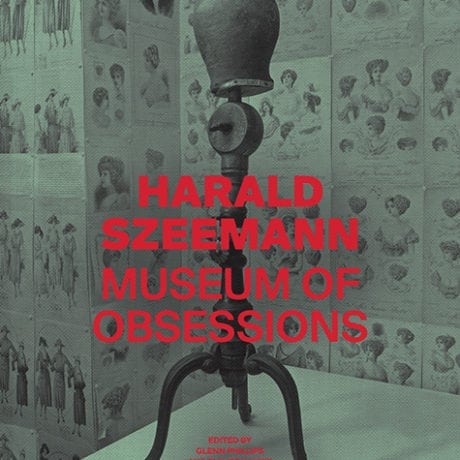

In his later years, Szeemann settled in the Italian region of Switzerland known as Ticino. The area is celebrated for its hilly expanse, known as Monte Verità, to which Szeemann was no doubt drawn for its own artistic legend. At various moments in time Verità had been home to a checkerboard of cult factions: nudists, anarchists and artists alike. It was in Ticino that Szeemann set up his own private curatorial factory, christened the Fabbrica Rosa. In this rose-coloured bunker was a personal library of over 26,000 books, meticulously arranged according to Szeemann’s own idiosyncratic ordering. It is this colossal archive which gives shape to the ongoing multi-stop exhibition (which moves next month to Kunsthalle Düsseldorf) and accompanying book, Harald Szeemann: Museum of Obsessions.

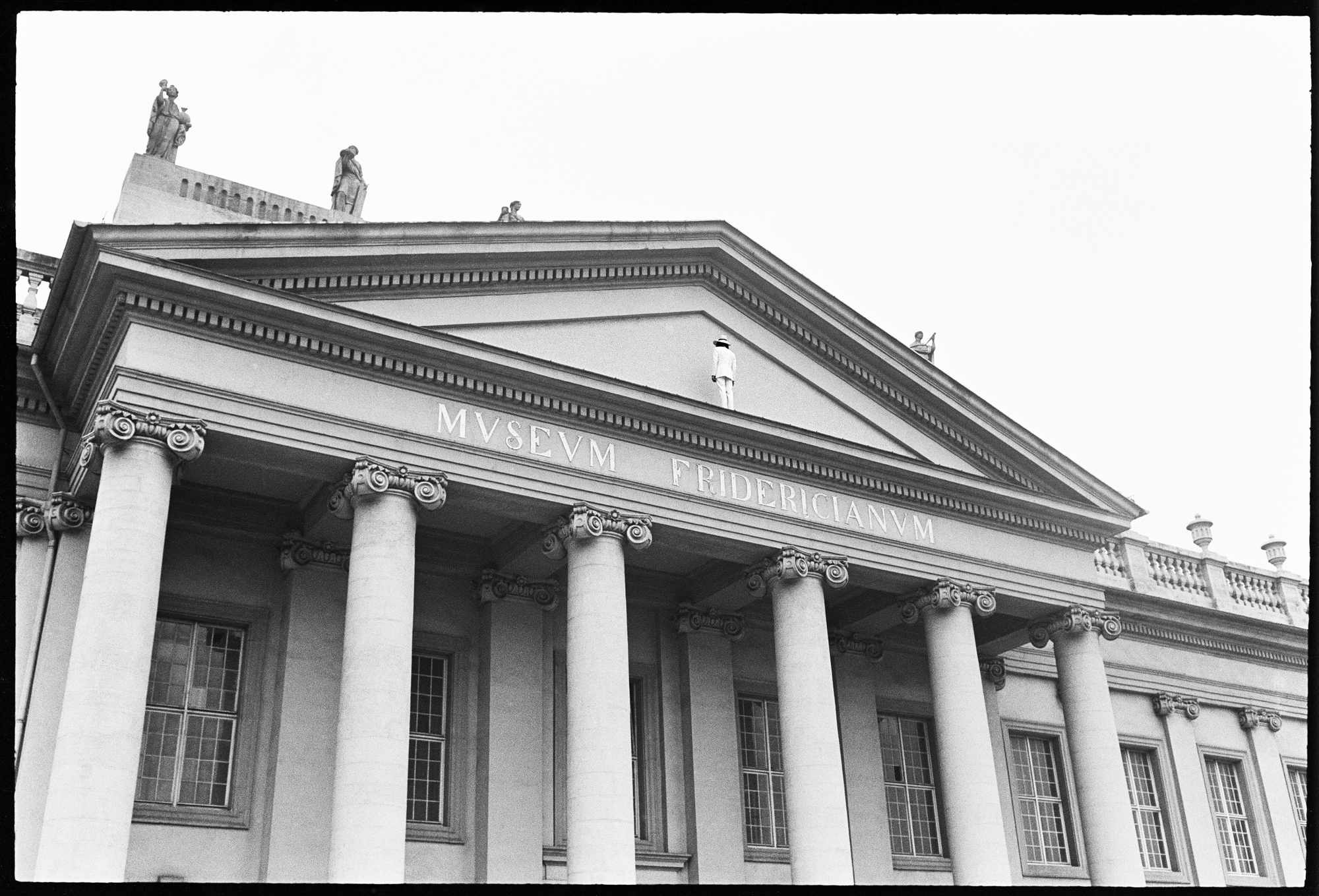

Beyond being a record for all the crucial exhibitions which made up Szeemann’s practice, this book contains copious interviews with colleagues and artists who worked intimately with the curator, figures such as Christo, Tania Bruguera and arte povera figure Gilberto Zorio. It was thanks to Szeemann that Christo and Jeanne-Claude were first able to execute their dream of wrapping a building entirely in cloth, which they did for the golden anniversary of the Kunsthalle Bern in 1968.

“It was thanks to Szeemann that Christo and Jeanne-Claude were first able to execute their dream of wrapping a building entirely in cloth”

Those aware of Szeemann most likely know him to be the exhibition organizer of When Attitudes Become Form, the watershed show at Kunsthalle Bern in 1969 that helped define post-minimalism, and Documenta 5 in 1972, a radically divergent presentation in which performances and art happenings coalesced into major exhibition programming for the very first time. As Megan R Luke describes in her essay “An Art History of Intensive Intentions”, Szeemann utilized these monumental shows as a means for artists to bring about their Gesamtkunstwerk—total work of arts—in spaces uncompromised by the usual exhibition fetter. With his, Szeemann enabled the total, multi-sensory environments that defined the work of artists such as Marcel Broodthaers, Joseph Beuys and Paul Thek, paving the way for a new medium of art that defies categorization.

One of the greatest strengths of this tome, which has been the result of a seven-year process (the Getty Museum acquired Szeemann’s archive in 2011) is the attention given to some of the more personal and little-documented exhibitions that Szeemann mounted, all of which were classified under his concept, Museum of Obsessions. The most intimate and compelling of these shows is undoubtedly the 1974 exhibition Grossvater: Ein Pionier Wie Wir (Grandfather: A Pioneer Like Us). Staged in an apartment that would become the curator’s home, the exhibition was dedicated to Szeemann’s grandfather Étienne “Stephan” Szeemann, a Hungarian born hairdresser who invented the world’s first permanent-wave machine for salons.

Every doodle, telegram, news clipping, contact sheet and phone number is saved, a few hundred make it to the book. Compliments and insults are shuttled back and forth in correspondences with figures such as George Brecht, Marcel Broodthaers, Lucy Lippard and Méret Oppenheim. Address books note the contact information for every blockbuster artist imaginable: Sol Lewitt, 117 Hester Street; Robert Morris, 186 Grand Street; Claes Oldenburg, 1404 East 14th Street—each location eliciting a vision of a studio hovel in the former ghettoes of what were then ungentrified neighbourhoods.

Replete with installation photography and more ephemera than you could fit into three lifetimes, this book does justice to a figure who expanded the field of curating to be a limitless means through which to re-envision what we consider art.