There is a myth, writes Alice Hattrick in their new book, Ill Feelings, that to be ill is to hide, “that to be inexplicably ill and dependent on the care and support of others is a choice, a way of getting out of what you don’t want to do, a choice that clever, deceitful young women make for themselves”.

It’s a myth, Hattrick continues, that harms everyone with a chronic illness, that confines some women inside and shuts others off from legitimate illness experiences. It makes illness out to be a choice, rather than a necessity, something only privileged people can afford. It’s a myth that Hattrick, and a handful of contemporary artists, intend to bust.

In 1995, Hattrick’s mother collapsed on the kitchen floor with pneumonia. She never fully recovered and was eventually diagnosed with ME, or Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS). Hattrick developed similar symptoms (sore throats, tummy aches, day-long headaches, mood swings) and would later also be diagnosed with ME/CFS, and then fibromyalgia.

At the time, though, their mother was told that she and her daughter had a “shared hysterical language” and that she was making her daughter ill. “My apparent mimicry of my mother’s symptoms,” writes Hattrick, “reflected badly on her as a mother.”

Ill Feelings combines memoir, biography and medical history to reckon with the nature of unexplained and invisible illnesses—those of Hattrick and their mother, as well as novelist Virginia Woolf, diarist Alice James, the poets Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Emily Dickinson, and the artist Louise Bourgeois. The latter once asked, “What’s the use of talking, if you already know that others don’t feel what you feel?”

Bourgeois’ own mother appears in her art in the form of a spider, a creature at once protective and vulnerable, fearful and feared. Bourgeois tussled with anxiety and depression, making art to stay sane and to “give meaning and shape to frustration and suffering”.

London-based artist Sarah Davis

was studying at City & Guilds when she was diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma. Originally her treatment was due to take six months. When she required an additional year of treatment, including a stem cell transplant, her art making shifted.

“That was when I felt the greatest loss, I think, with the relapse,” she says. “So, I went on a mission of reclamation.” That reclamation came about through PUSH, an ongoing project that Davis began from the bedroom while receiving treatment in 2017. “I got to a point where I needed to make something tangible for myself and for other people,” she says, “to understand the physicality of sickness.” She needed what Bourgeois described as “the physical acting out”.

“My illness is a passive thing that I’ve come to accept. I can’t escape it, so I have to create a space that works for it”

Davis bought clay and plaster, two simple sculptural materials sourced from the earth, and started making replicas, or relics. The first was Moulage (1), an impression of the PICC line in her arm, a long thin tube used to administer drugs and take blood. “I remember wrapping it in clingfilm, pressing clay against it and taking a plaster cast, and just loving this gentle transformation from something sitting on my body to something that I could hold and have a bit of power over,” she says.

Next came functional objects, from empty pill packets to Pill Cup

(2019). “For me, cancer was such a liquid experience—the way you’re treated and measured is often in liquids—and making a cup felt like the ultimate reclamation.”

Whereas the plaster casts of pill packets have a quiet intimacy about them, the sterling-silver cup resembles an ancient artefact. “I see it as a traumatic object, but it’s contained the trauma and made it more manageable,” says Davis.

“Medical trauma is strange,” she continues, “because you’re constantly signing consent forms. You have autonomy in a way in what you’re taking, but you also don’t have any at all. It’s a strange form of objectification. I wanted to make these objects of pain that told the story of my body in that moment.”

“It’s why I want to make work. I want to say, ‘Hey, we exist, we live our lives, we are not stereotypes’”

In Ill Feelings, Hattrick sifts through their mother’s health records to tell the story of both their bodies. Early on, they describe their mother’s body as if it’s “not a body at all”, as if it’s “a machine malfunctioning… faulty, or broken”.

Hattrick considers the limits of language when conveying pain, and the idea that their mother’s language for ill feelings is “incomprehensible” to doctors. They cite Woolf, who wrote from her sick bed of the need for a “new language” for pain, one that is “primitive, subtle, sensual, obscene”.

Italian artist Nina Silverberg describes having a kidney transplant and taking pills to prevent her body from rejecting the foreign object inside her as “a Frankenstein thing”. She’d been tired for years, and put it down to mental health, until, when she was 22, she took a blood test and learned her kidneys had failed.

“We spend a lot of time trying to understand how we feel metaphorically, when sometimes the problem is material more than anything else,” Silverberg says. During dialysis she struggled to make art, but as she regained her strength, she became more motivated.

“I had all these images on my phone and what stood out was a window, which I started abstracting,” she says. “It was less about my illness and more about the feeling of being caught in a liminal space, wanting a refuge and at the same time wanting freedom.”

Silverberg’s recent paintings of pared-back buildings and slanted rain waver between figuration and abstraction. They’re seemingly simple, and simply beautiful. She wants to create calm spaces in art and in life: “My illness is a passive thing that I’ve come to accept. I can’t escape it, so I have to create a space that works for it.”

“I got to a point where I needed to make something tangible for myself and for other people, to understand the physicality of sickness”

She says the paintings of windows and blinds she made before the pandemic were about a singular experience. “They were repetitive, which was helpful,” she explains. “I think within repetition there is a form of meditation and self-exploration.” With her new work, she’s looking outside herself, “seeing what these topics mean in a bigger sense.”

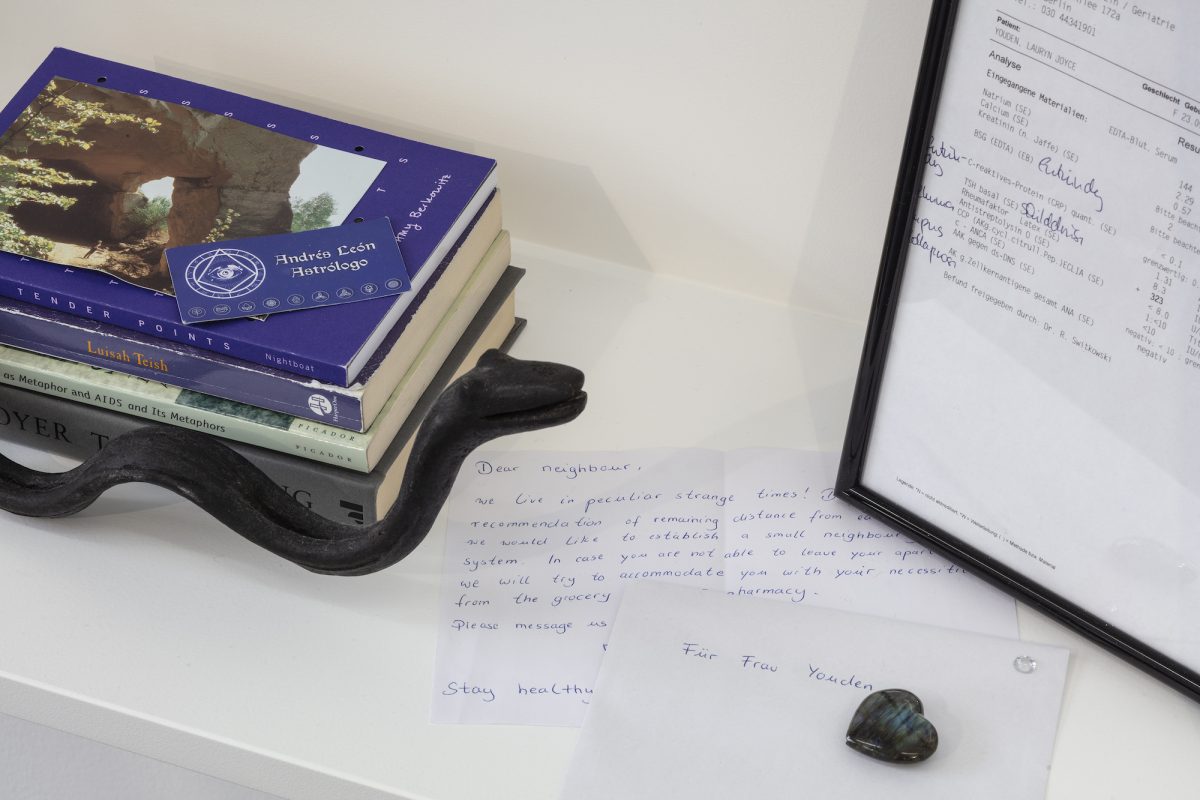

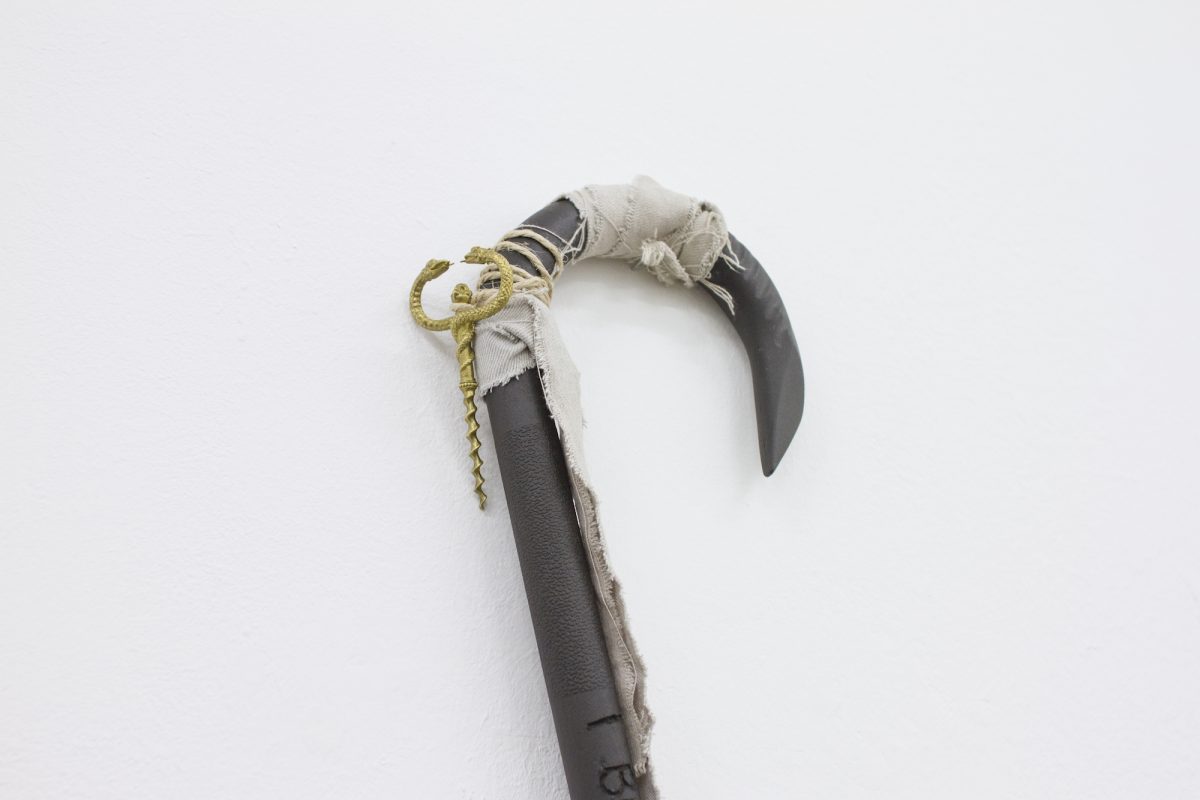

Lauryn Youden, From the Great Above she opened her ear to the Great Below (install), 2020. Photo: Timo Ohler

Canadian performance and installation artist Lauryn Youden’s interest in the history of medicine and ‘alternative’ healing practices stems from her desire to get to grips with her own illnesses and those of her mother and grandmother.

After experiencing anxiety and depression as a child, Youden (like Hattrick) was diagnosed with fibromyalgia. “I think I’ve had it for most of my life,” she says. “I just thought, everyone is this exhausted at the end of the day, or in so much pain that they get migraines.”

Inspired by the experience of being chronically ill, her writing practice and performances are a path to catharsis. Altar-like installations are filled with medicine, essential oils, candles, dried flowers, books, and other items that help her navigate an able-bodied world. “I want to create a kind of archive that’s accessible to others,” she explains.

In Ill Feelings, Hattrick writes that they believe people deserve to be allowed behind the scenes. Guilt and shame are tied up with illness (especially that which is unexplained or invisible) and they prevent us from sharing our experiences.

Youden believes that it’s only through making work and reading poetry and other illness narratives that she’s begun to understand herself. “It’s nice to feel seen and heard,” she says. “That’s an essential part of texts like this, and it’s why I want to make work as well. I want to say, ‘Hey, we exist, we live our lives, we are not stereotypes.’”

Chloë Ashby is an author and arts journalist. Her first novel, Wet Paint, will be published by Trapeze in April 2022

Images courtesy the artists