We are constantly scanning for updates and upgrades; in our bodies and brains (most of us covet wisdom, but wish to defy age), in the environment around us, and the technology at our fingertips. “Cutting-edge” devices might swiftly lose their sheen, growing clunky and blunt, yet the work of Berlin-based electronic music pioneer, co-creator of Ableton Live software (which revolutionized contemporary DJ sets) and audio-visual artist Robert Henke proves that even undeniably retro tech retains transformative qualities.

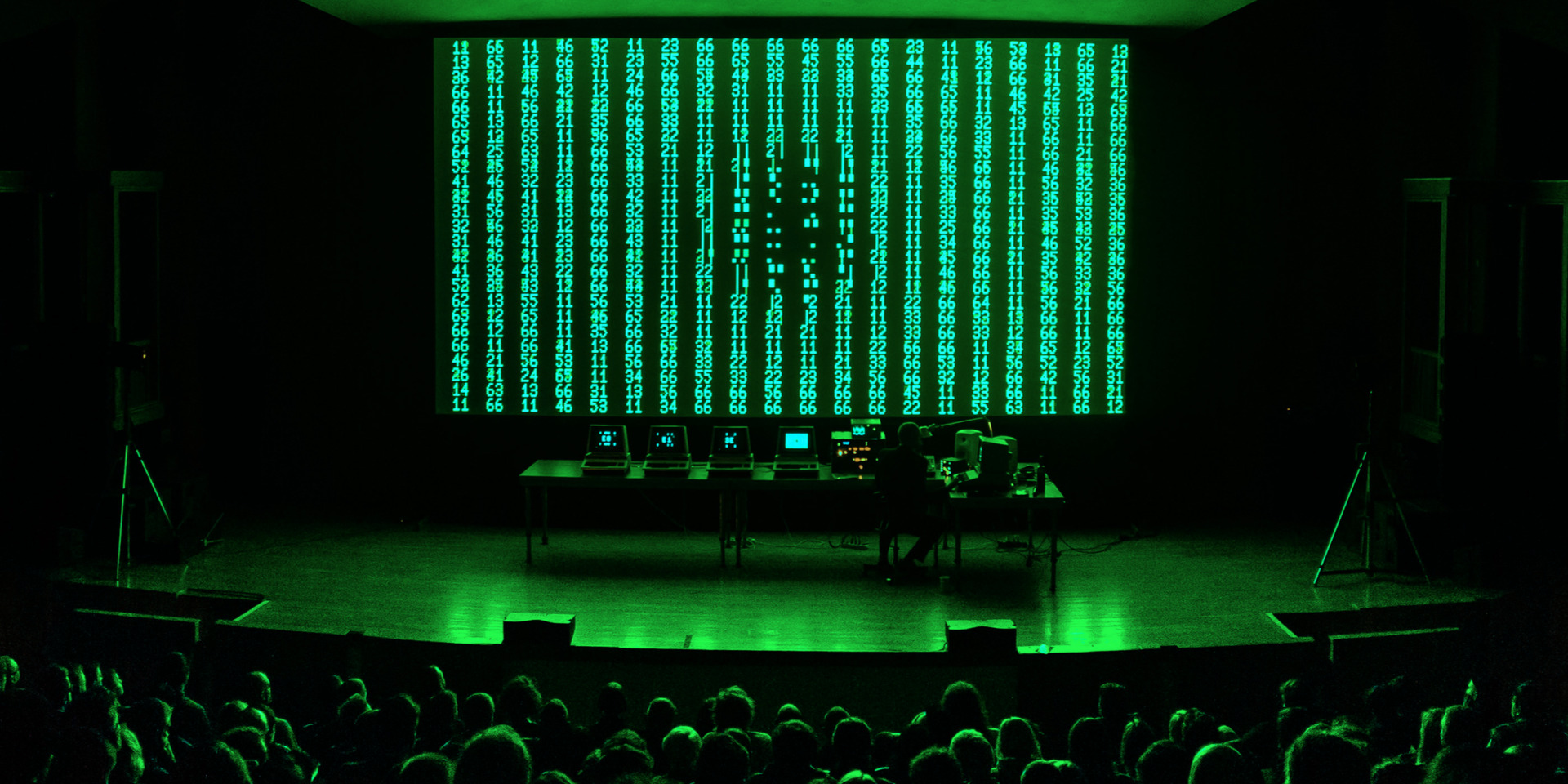

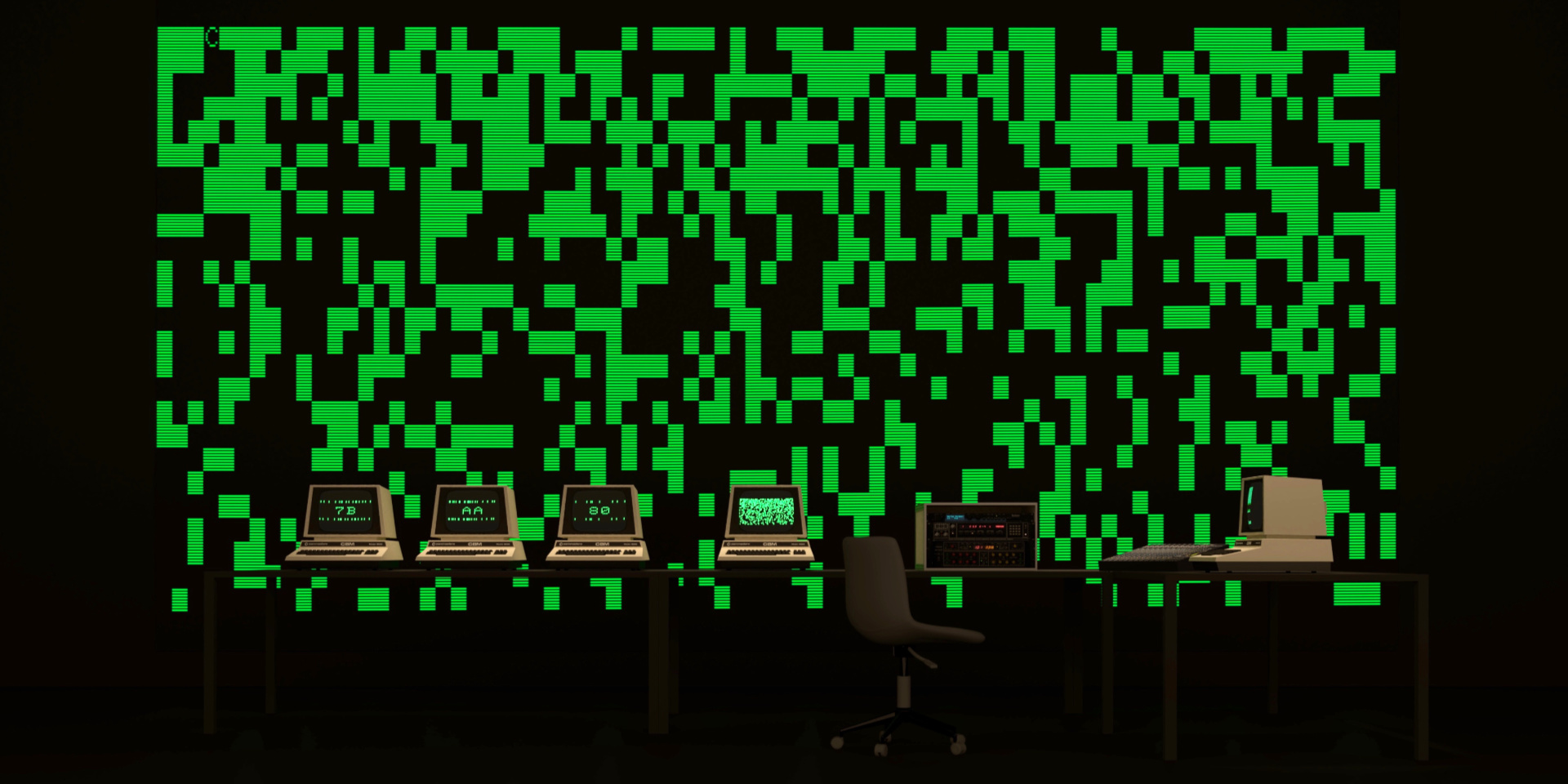

Henke’s latest performance project, CBM 8032 AV, gives centre-stage to a “line-up” of five CBM [Commodore Business Model] 8032 computers. These chunky, angular models were originally released in the early 1980s, at a time when Henke himself was first experimenting with computer programming at school. A few years ago, he bought a CBM 8032 on eBay “just for fun”, and quickly became inspired by their limitations, as well as their potential.

“Coding software for these systems is so radically different than how you work today,” explains Henke. “I realised that the inherent limitations provide an interesting challenge. It’s minimalism by design. You can’t do much with those computers in real time, so everything has to be highly structured and reduced. And there a very contemporary idea of artistic work comes back in… I started to explore how far I could push it. And at some point, the project had to become teamwork because the workload exploded, and the scope of the project expanded from ‘doing a work for a gallery using one machine’ to ‘developing a networked system of five computers running an AV performance’.”

“The inherent limitations of coding for these systems provide an interesting challenge. It’s minimalism by design”

Here, additional coding for CBM 8032’s visual routines was created by Anna Tskhovrebov. The “ancient” computers’ capabilities were also enhanced using hardware which would have been available in 1980. The resulting expression feels suspended between eras and interfaces: retro/futurist, man/machine. Like much of Henke’s work, it is also strangely emotive; there’s something hugely nostalgic, as well as weirdly chic, about elderly tech.

The hypnotic, flickering monitors of the CBM 8032s make me recall my own first computer, as a mid-‘80s kid: a cut-price Commodore 16. Even back then, it was a limited computer, with a sixteen kilobyte memory (today, basic smartphone usage would involve an average 5GB, or 5,000,000 kilobytes), but I still sometimes dream about its graphics and sounds. Once, I followed a simple programme to turn its keyboard into a ten-note “synth”, and I felt like I was serenading outer space.

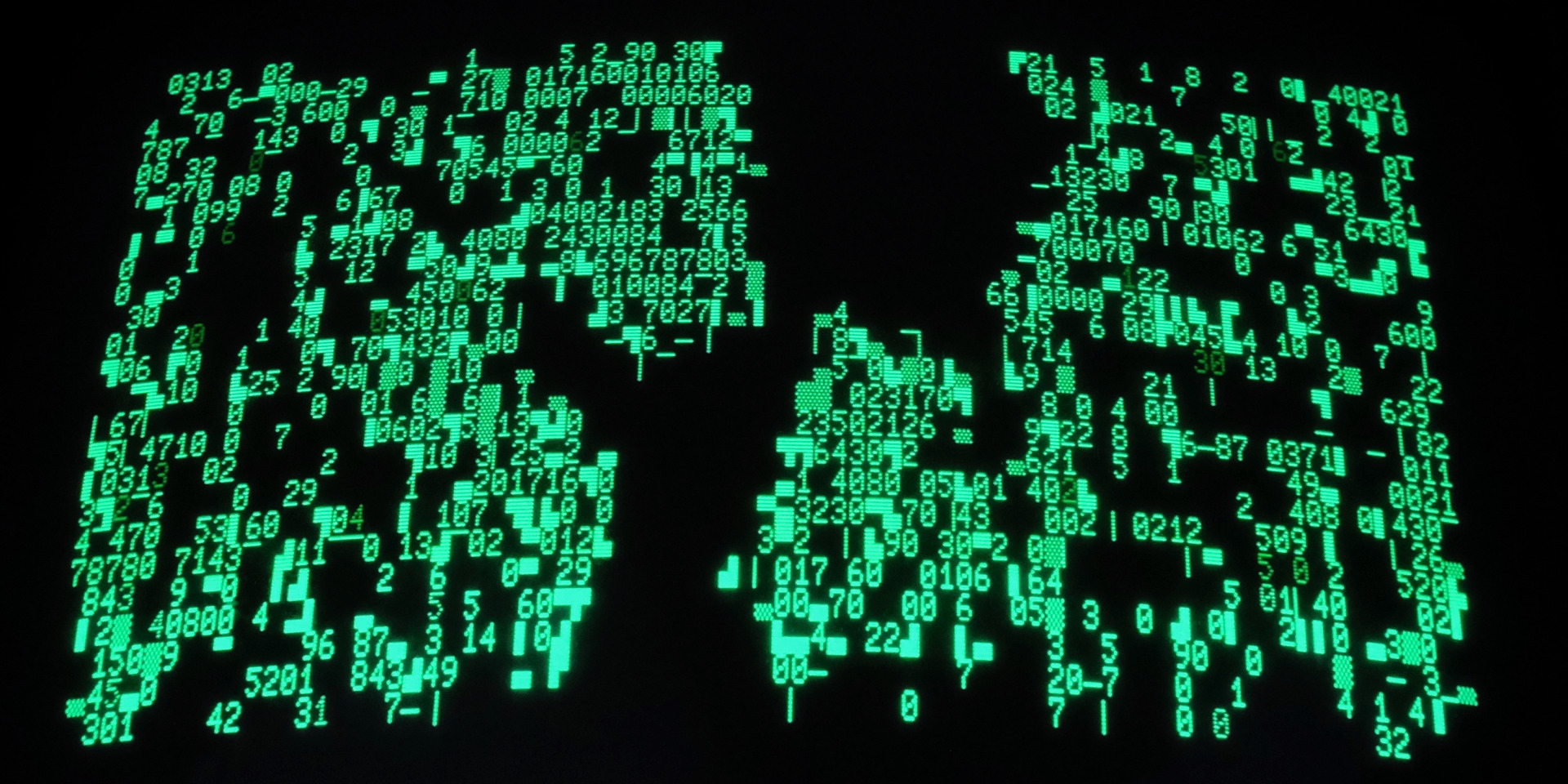

Henke displays a similar attachment to the CBM 8032: “First of all, those green cathode ray displays look really cool, in a way that’s got lost with more modern technology, just from the purely visual side,” he enthuses. “And then there is the cultural framing. Computers like these were once the future; now they’re the past, but they’re very alive as popular imagery: there’s no feature about computer crime without green characters on screen. Or think of the opening scene of the first Alien movie…”

“People who know these machines will hopefully be impressed, because everything they’ll see will be familiar, yet completely unseen and unheard of before. All the image generation is based on using a set of perhaps fifty “graphic symbols: icons of 8 x 8 pixels, as part of the ‘PetASCII’ character set, and that’s it. Sound-wise, I still can’t believe we were able to create that much power with a single 8 bit CPU and no additional sound chip or hardware synthesisers involved. The sound is raw yet refined.”

Earlier generations of computer graphics pioneers, in particular German innovator Manfred Mohr (whose “algorithmic art” experiments began in the late 1960s) have fuelled Henke’s own inspirations, although most of all, he seems fired up by the challenge of limitations. This creative tension obviously applies to CBM 8032 AV, as he says:

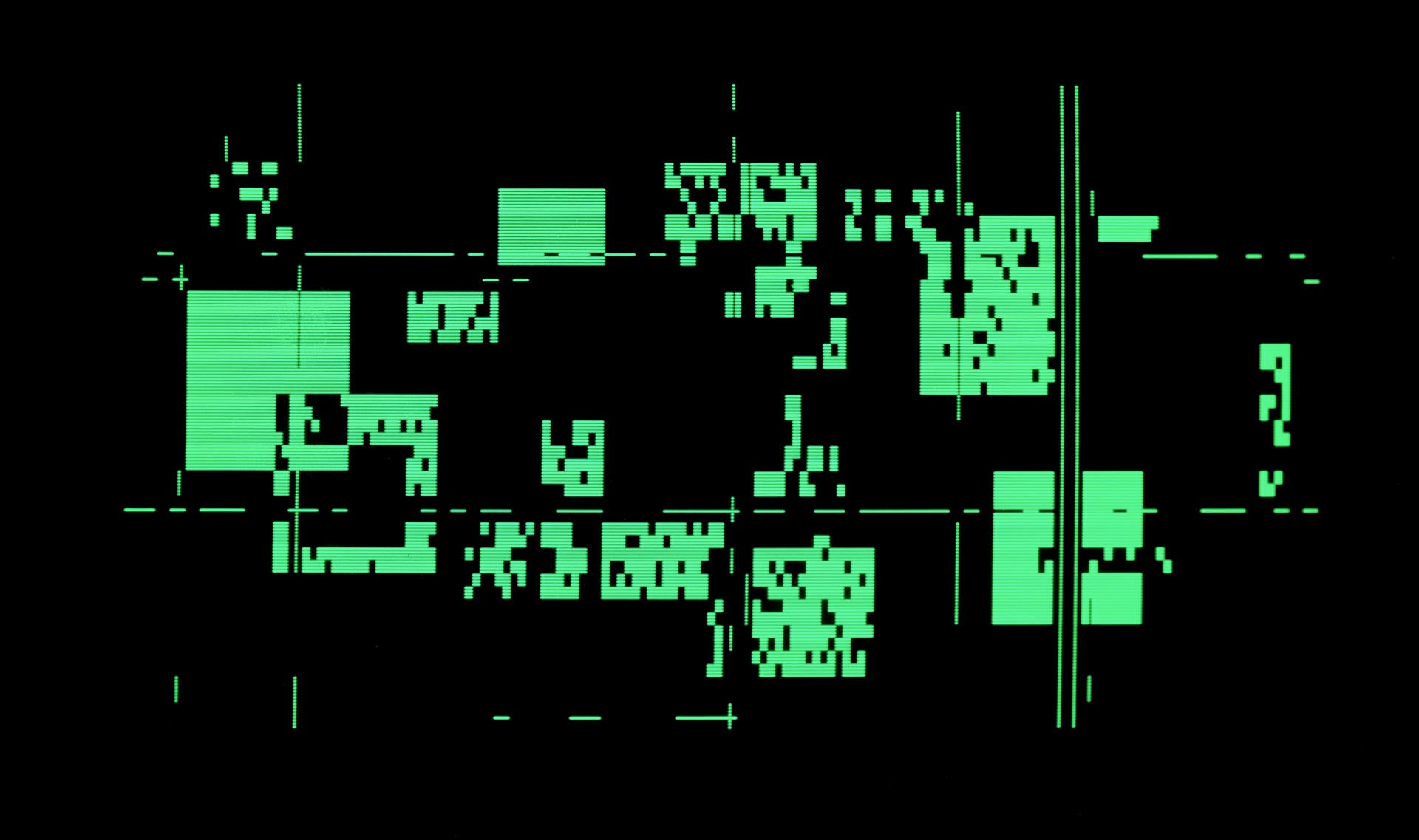

“We learned things from scratch; we had to understand a lot of new old concepts and dive deeply into the hardware to make it happen… Imagine, these computers do not even have something like a standard network connection or the software, firmware and hardware for it! So we were even inventing our own ‘interrupt driven parallel data bus’ hardware just to get the computers to talk to each other.”

“A lot of inspiration came from simply trying out what can be done with small, efficient code and still looks good. The aesthetics are often the result of that. If you cannot scroll and create new symbols at the same time, do it in sequence, one after another. And suddenly there is visual rhythm, emerging out of technical necessity.”

Throughout Henke’s work, the allure of “limitations” actually yields prolific, far-ranging projects, including the laser-based Lumiere performance series (now in its third incarnation), and sleekly poetic visual installations such as Fragile Territories [2012] and Destruction Observation Field (premiered in 2014, and presented this July at Banffy Castle in Bontida, Romania).

“Computers like these were once the future; now they’re the past, but they’re very alive as popular imagery”

“[Laser] is a very limited medium, but it has a very specific visual quality,” says Henke. “The combination makes it hard to create something unique and convincing, but it’s also rewarding. Limitations are usually a good thing when creating; they enforce clarity.”

Fans of Henke’s clubbier output will be pleased to hear that he’s also presenting an AV surround performance by his acclaimed electronic music act Monolake

in Medellin, Colombia, at the beginning of February, and that CBM 8032 AV also promises a “punchy” pulse. (“The physicality is there in parts,” promises Henke).

I wonder whether art created with technology can ever really be “ageless”, but Henke is in no doubt: “Sure,” he insists, brightly. “Because technology is a huge field; the invention of the pipe organ or the piano or the violin or even of a simple flute is nothing but technology. But it helps not to use the ‘latest’ technology, in my opinion. If one is using older media, a lot of artists have already developed works, and one can more easily find their own signature within that field. When working with new technology, there is always the risk that you’ll do something that later will be seen as the ‘obvious’ first thing to do with the medium, which is not necessarily the most interesting usage…”

So far, across his repertoire, Henke has resolutely avoided the ‘obvious’, highlighting hidden spaces and unexpected sensations, including arguably the most memorable aspect of CBM 8032 AV

: “It seems we managed to implant some soul in these old machines.”

CBM 8032 AV is at Berlin CTM Radialsystem, 29 Jan; and Krems, Austra, 1 May

VISIT WEBSITE