India’s vast geography, heterogeneous population and diverse linguistic culture make truly national news something of a misnomer. Events, movements and injustices can occur without crossing state borders, their impact localised and sometimes deliberately slowed by powerful authorities.

Manipur, a northeastern state bordering Myanmar, lies directly east of West Bengal. Photographer Rohit Saha was born here, but it wasn’t until his Masters’ degree in Gujarat (on the other side of the country) that he learned of the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act, a dark ongoing chapter in India’s story that brutally informs the back story of this image.

The act, first passed in 1958, allows members of the national military to execute anyone on suspicion of terrorism or anti-state involvement without detention or trial, and to search properties without warrants. It covers a number of northeastern states and territories declared ‘disturbed areas’ (including Manipur).

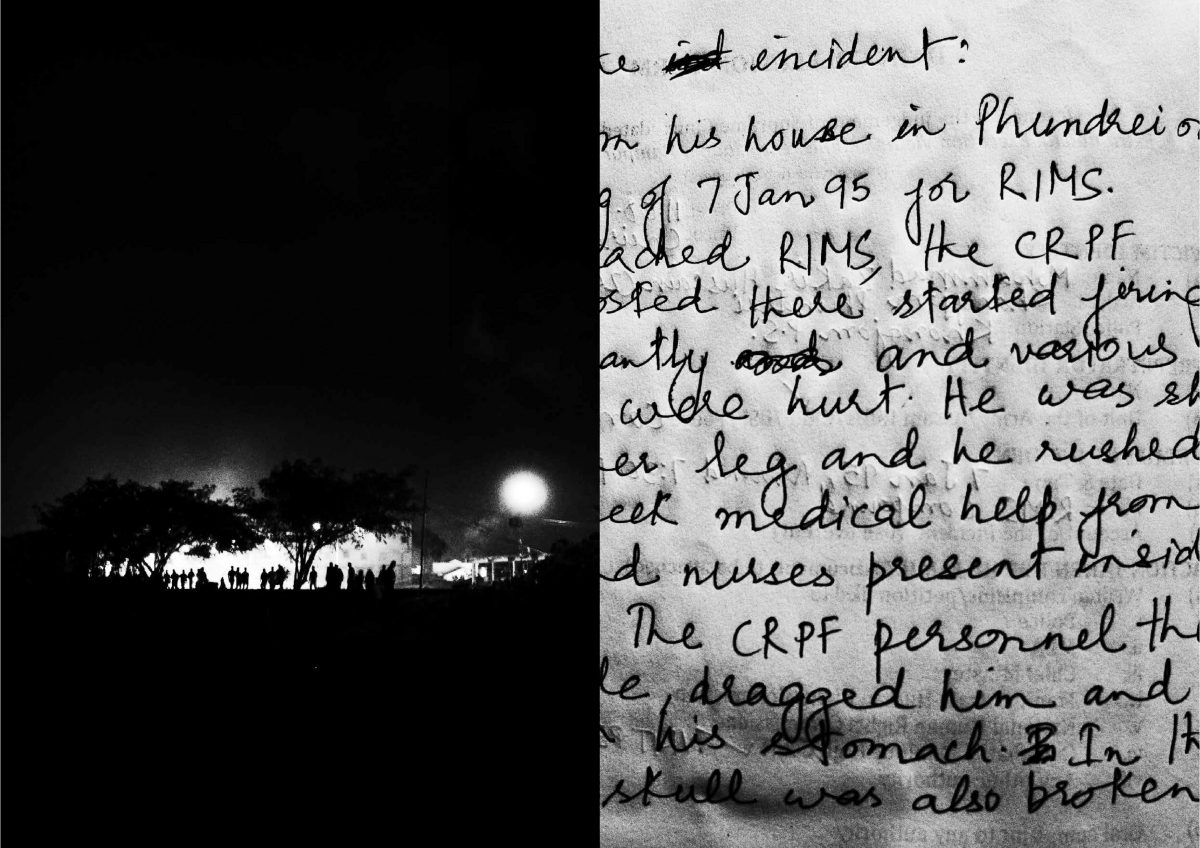

It was under this act that an Assam paramilitary group shot and killed 10 civilians waiting at a Manipur bus stop in a village named Malom in 2000, in an event that came to be known as the Malom Massacre. For 16 years, a local peace activist and poet Irom Sharmila campaigned for the act’s repeal via a hunger strike that was only broken in 2016.

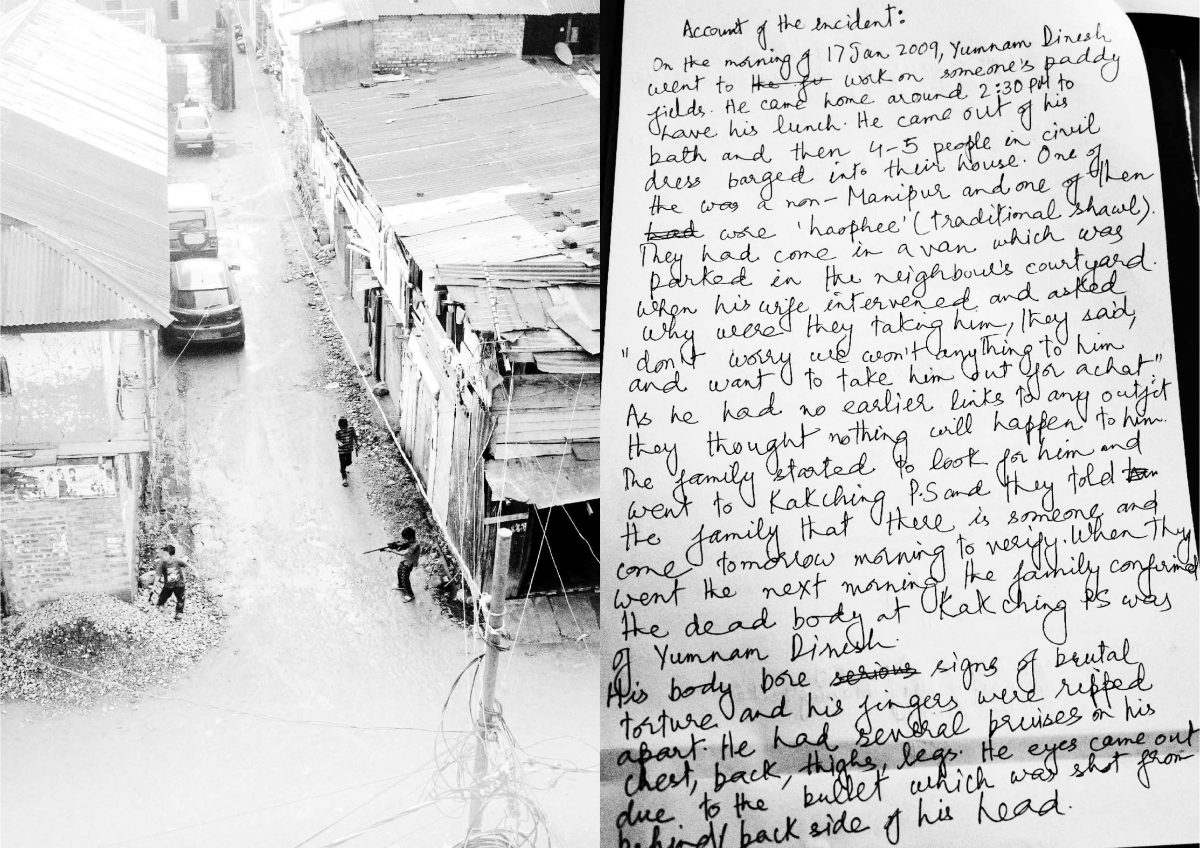

Saha, then a photography student in Gandhinagar, was shocked by his own ignorance of his country’s own brutality. For his Masters’ project, he travelled to Manipur to shadow Sharmila and volunteer with the Extra-Judicial Execution Victim Families of Manipur (EEVFAM) trust. He accompanied them on fact-finding pursuits, data logging and victim support visits, using a basic point-and-shoot camera to document his surroundings.

“Under this act, an Assam paramilitary group shot and killed 10 civilians waiting at a Manipur bus stop”

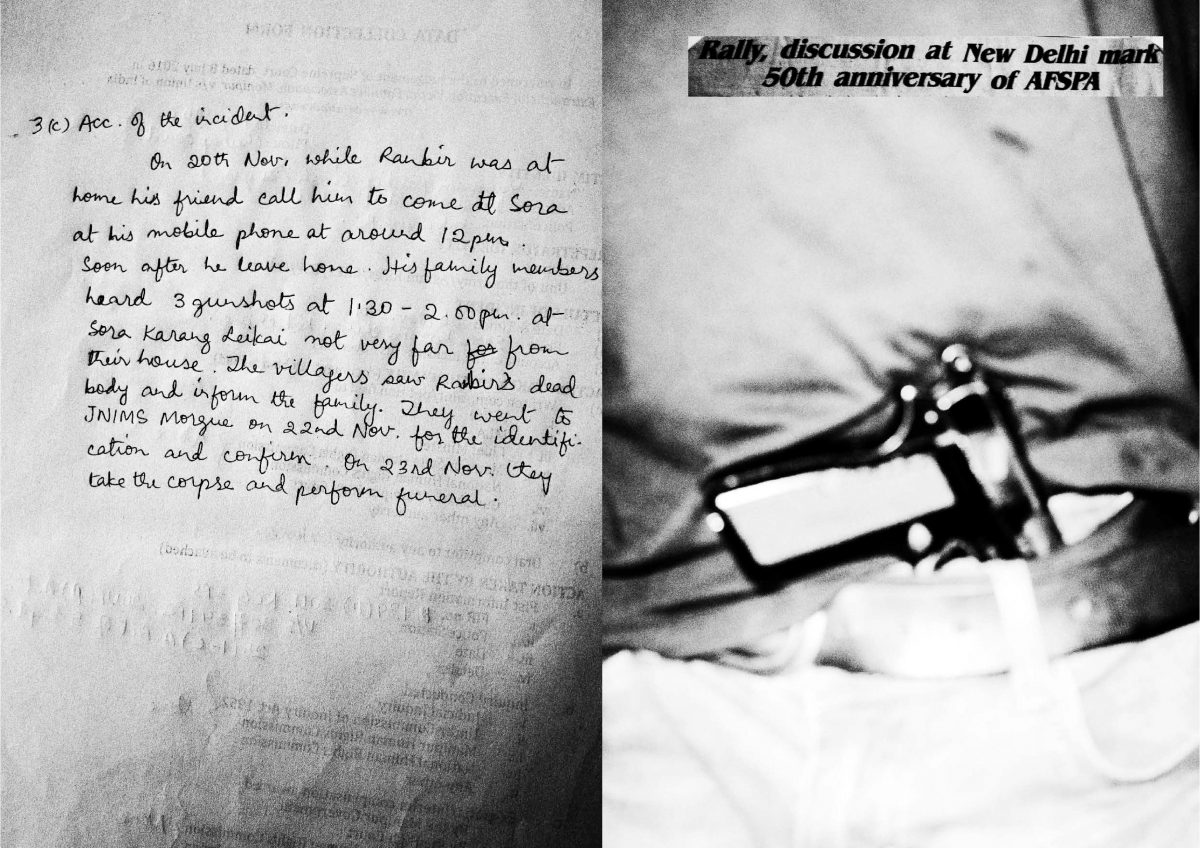

Much of Saha’s work involved digitising witness testimonies so they could be used in Supreme Court ‘terrorism’ trials. “I thought the Malom Massacre was the worst that had happened,” he says. “But here I was looking at 33 years of violence.” His image-making became secondary to the wider project for justice and education. “My main understanding was, yes, I have to photograph, but I wanted to learn myself what really happened.

His project, named 1528 for the number of alleged extra-judicial killings in Manipur between 1979 and 2012, includes protest imagery and fragments from reams of evidence he observed while working with the group. Portraits document EEVFAM’s home visits to victim’s families, many of whom delayed reporting their relatives’ disappearances for fear of police repercussions from these ‘fake encounters’.

This image shows a life scarred by these unexplained losses: the younger brother of the woman pictured went missing several years ago, close to Manipur’s border with Myanmar where the family still resides. “She was angry,” Saha says. He couldn’t understand her dialect, but he felt her rage as she answered their questions. “Angry at the condition; the situation; helplessness.”

Ravi Ghosh is Elephant’s editorial assistant