On the idyllic Porquerolles Island, visitors to the Villa of the Carmignac Foundation are greeted with a mysterious “plant-based drink”, and encouraged to explore the art barefoot. Luckily, temperatures rarely dip below twenty degrees. “The particularity of the place is its spirit: all the above-mentioned elements come together to create the most favorable conditions for an encounter with art to take place,” says its director, Charles Carmignac, the son of a billionaire banker, Edouard, who founded the Carmignac Foundation in 2000. His father’s collection is the result of a personal and direct contact with art and artists: he started his collection back in the 1980s in New York, where he had met artists like Basquiat and Warhol. Later he developed a keen interest in photojournalism, a continuum in the collection since.

“Villa Carmignac questions our presence in the world and wishes to provoke, through shocks and emotions, real internal questions,” he adds. “We want to change the paradigm in our relationship to nature by not thinking of it as just our environment, but as a whole of which we are part.”

Edouard Carmignac created the foundation “with the goal of sharing contemporary artistic creation with as many people as possible. Everyone is at liberty to create a foundation according to their own sensibilities, charitable aims or the subjects which particularly concern them,” Carmignac notes. “To my mind, the act of sharing is an important part of all these projects. To create a foundation is also to leave one’s mark on the history of art.” The only sticking point is you have to get out to Porquerolles, a short ferry ride from the French Riviera—a kind of luxury pilgrimage, that in reality might be prohibitive to many visitors. Since opening five months ago they have had 70,000 visitors, Carmignac says. The figure exceeded their expectations, but obviously falls short of the more accessible museums in Europe’s cities. (Tate Modern reports around half a million visitors per month.)

In Milan, Miuccia Prada and Patrizio Bertuelli had a similar idea in the 1990s, driven by “their personal curiosity, passion and interests in the fields of art and culture”, I am told by Astrid Welter, Fondazione Prada’s head of programmes. “In the early nineties, there were not as many private art foundations as there are today, so it played a pioneering role especially in the European context. Fondazione Prada was created as a cultural institution separated from the business of the fashion brand, in order to develop its own mission and identity.”

Prada and Bertelli were already established as patrons of the arts and avid collectors with connections to world-class artists, long before they were set on taking on a role as “cultural and artistic activators”, Welter explains. They began by inviting international artists to do exhibitions in temporary venues across Italy in the 1990s, only opening their first permanent location in 2011, in a historic palazzo overlooking the Grand Canal in Venice. The opulent Milan galleries, designed by Rem Koolhaas, opened in 2015, and became the foundation’s HQ. A more centrally-located space in Milan, Osservatorio, primarily showing photography, was inaugurated a year later. Locally, the Prada brand name and the unparalleled offerings of space across the foundation’s venues undoubtedly prove useful in persuading big artists and collections to participate in the programme. Locally the Foundation is now part of the Milanese identity, as well as an attraction to the city in its own right.

The Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris has staged some of the most important exhibitions on modern and contemporary art in Europe in recent years—currently a major survey of Basquiat, presented with a huge display of Egon Schiele, is as researched and extensive as any museum show.

Foundations are certainly an exercise in elite branding—the associations of culture and activism build an idea of a high-minded megalith, and define the brand’s USP and taste. The Wes Anderson-inspired interiors of the bar at the Prada Foundation, rendered in the perfect Prada palette, for example, plant you inside the brand’s ideology. In the same way Carmignac—despite its remote location—wants to immerse you in an experience of exclusive natural beauty. Bringing in the world’s best architects, luxury foundations go to great lengths to create something you won’t feel at a museum. Fondation Cartier, in Paris’s 14th arrondissement, was designed by Pritzker Prize-winning Jean Nouvel; Frank Gehry did the Louis Vuitton Foundation, which opened in 2014 and cost $143 million. These are major additions to the cultural landscape. Visitors might never be able to afford an item at the brand’s store, but they are immersed in the experience of luxury.

When I visited the Prada Foundation, I saw an multimedia exhibition on the halcyon era of Italian television, complete with an installation of a set with plush carpets and crimson coloured velvet carpets.

“Our central question is ‘What is a cultural institution for?’ We may not have a complete and final answer, but we want to define ourselves as a foundation that is trying to understand what the purpose of a cultural institution is today,” Welters told me. “We believe that arts and culture are deeply useful and necessary, as well as attractive and engaging. They should help us with our everyday lives and our understanding of how we, and the world, are changing.”

The very nature of any art institution means that no major venue for the arts is truly independent of a political, social or economic impetus. When it comes to the art world ecosystem, the privately-run foundations I spoke to seem to see themselves as outside of it. Neither dependent on the market or government funding, it follows that foundations have an independent air.

“The Loewe Foundation was created in 1988 and its initial focus was poetry, including a prize which became a very important prize for poetry in the Spanish language. When I joined Loewe, I thought that as we make all things by hand, and because of my own personal interest in craft, the foundation felt like it could be a kindred spirit for both things. Plus there is the fact I felt like there was a lack of acknowledgement globally in terms of people who make things, so the foundation is there to elevate that concern,” Jonathan Anderson, head of the Loewe Foundation and the brand’s creative director, explained, when I asked why the brand wanted to set up a foundation and what it means to him.

“I don’t really see the Loewe Craft Prize as part of an art world system,” say Anderson. “I think it’s more like philanthropy in a different way—a platform to promote, ultimately.”

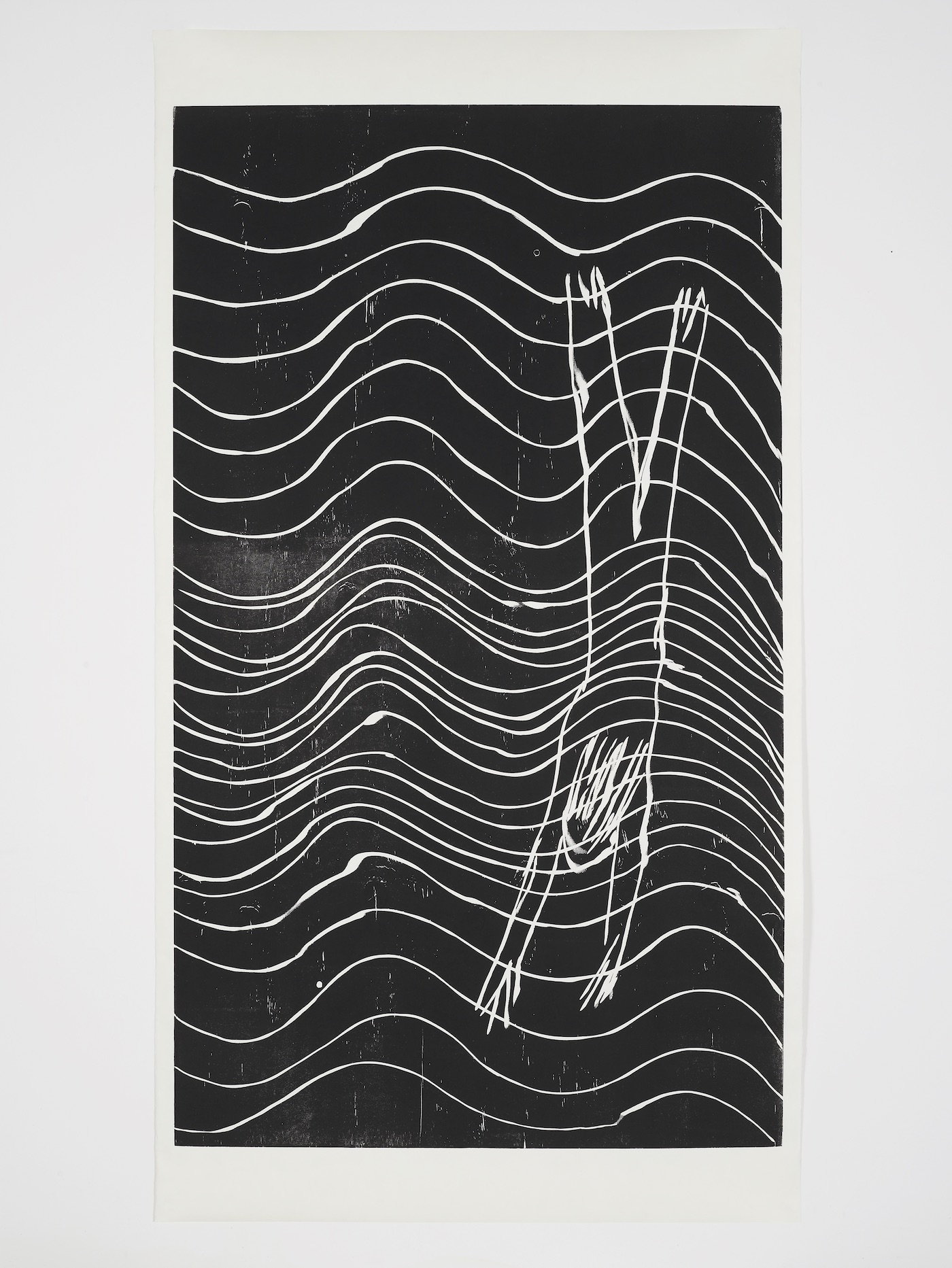

At Art Basel Miami Beach this year, the foundation has organized an exhibition of prints, textiles and ceramics by three artists (Anne Low, Andrea Büttner, Ian Godfrey) at its Design District store. The Craft Prize winner will be announced at the end of January, and the finalists presented in an exhibition in Japan in the Spring.

When the Louis Vuitton Foundation opened to the public, CEO Bernard Arnault told the Financial Times that “we see our role as bringing the artists we show at the foundation closer to the public, and encouraging a desire for innovation.” The relationship between art and fashion has always been amorous, and foundations are a more committed show of affection. Like them or not, foundations seem to be here to stay—compared to say, the concept store model that brands like Colette and Club Monaco pioneered. As budgets for the arts are slashed all over Europe, there’s no denying that the foundations have an increasingly important role to play in shaping art history.

“Above all, it is about sharing our common values: personal conviction and intuition, but also courage and team spirit,” Carmignac enthuses. “The foundation obviously has certain benefits in terms of image and notoriety, but it is also a source of inspiration for employees in contact with art and nature. To my mind, the act of sharing is an important part of all these projects. To create a foundation is also to leave one’s mark on the history of art.”