Emma Hart is the winner of the 6th Edition of the Max Mara Art Prize for Women. Following a residency in Italy–in Milan, Rome, Todi and Faenza–she is preparing for a solo show later this year at Whitechapel Gallery which will tour to Collezione Maramotti, Reggio Emilia in Autumn. She is also currently showing at London’s The Sunday Painter.

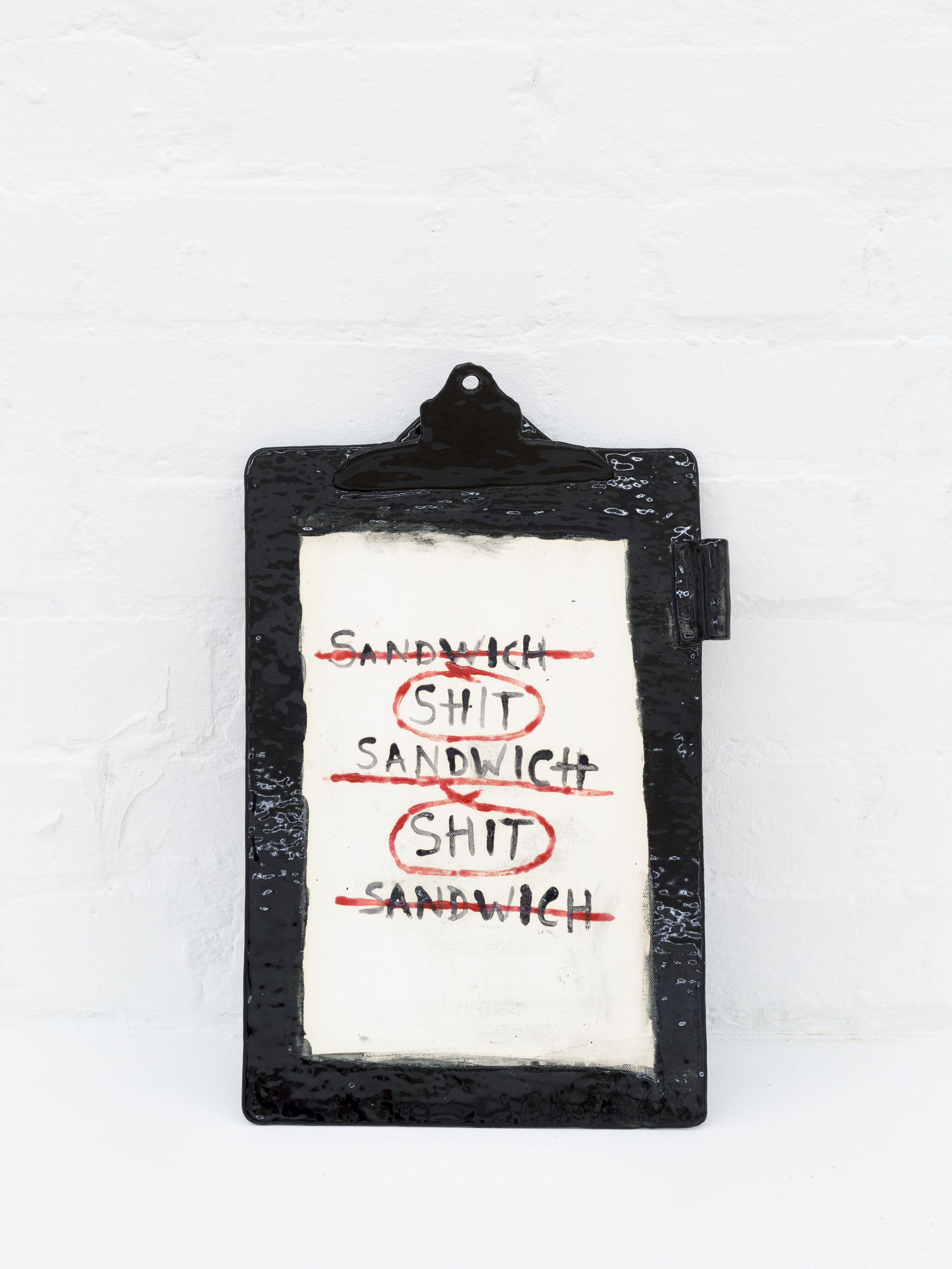

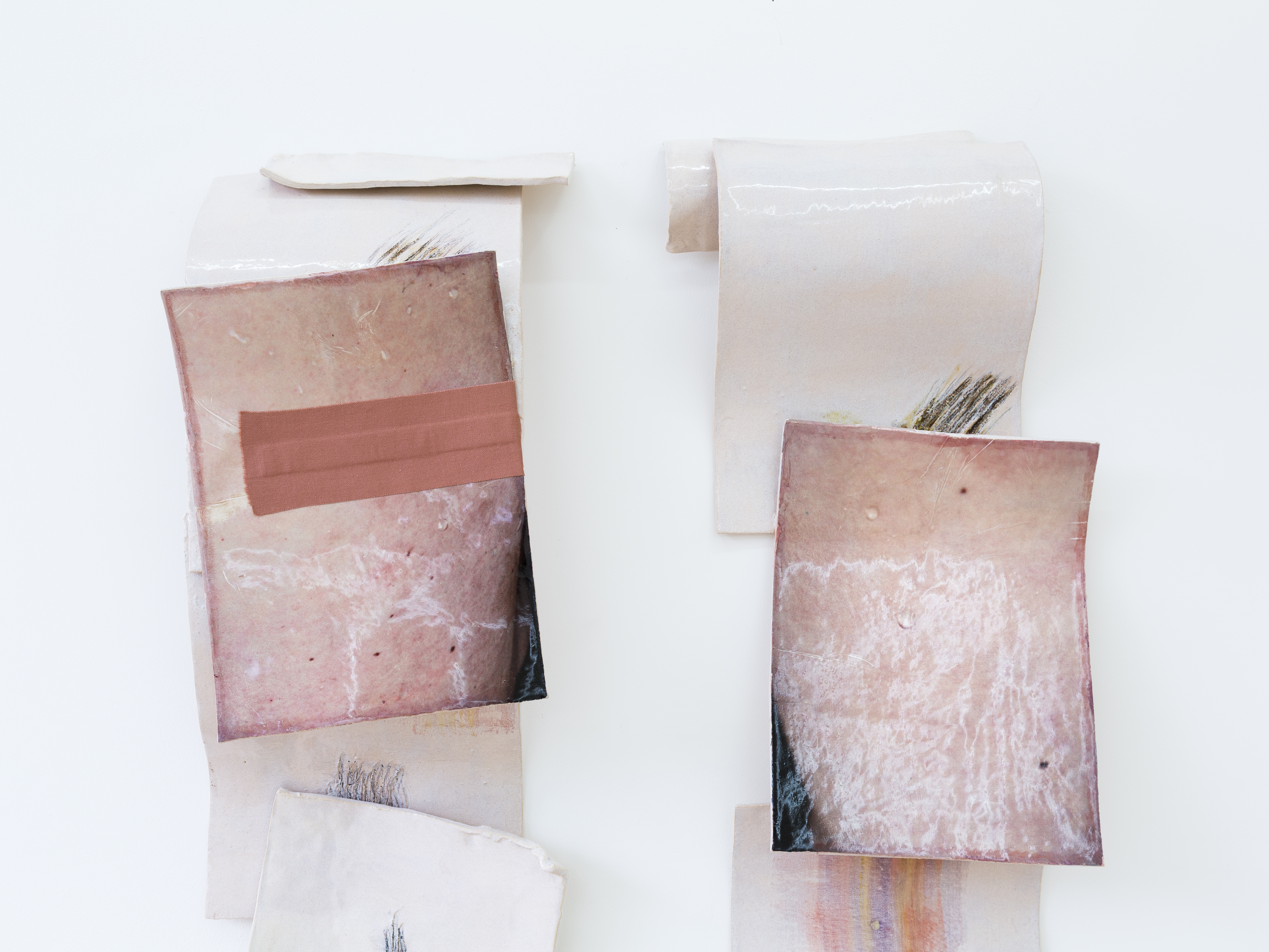

Emma Hart’s works are instantly recognisable. Crude, characterful and nearly always amusing–not in an obvious punny way, it’s more subtle than that–her sculptures are fun and full of life. Part of this is due to an avoidance of strict technique. Her forms are wobbly-edged and there’s a purposeful lack of a clean “finish”.

On winning the 6th edition of the Max Mara Art Prize for Women, which has taken her from 2015-17, the London-based artist brought her proposed residency to life. The proposal was split into various parts; focusing on the family and relationship psychology in Milan, looking at family structures in ancient Rome with Katherine Huemoeller, a researcher from Princeton University, researching at Alighiero Boetti’s studio in Todi, and, most recently, studying the production of ceramics at Museo Carlo Zauli in Faenza.

Although she has now returned to London to live, she will regularly be returning to Italy to develop the body of work that will constitute her final show at London’s Whitechapel Gallery later in the year.

The residency is described as being completely bespoke. Did you have a very clear idea about what you wanted to do from the beginning?

The shortlisted women are asked to put in a proposal of what you might do for six months in Italy, and that then carries forward. It was all moulded around my proposal.

What took you to the idea of family?

I knew that, rather than try out something new in my practice, I wanted to really embed myself in something I’ve already been thinking about within my work. One of those things is how an artwork makes a relationship with the viewer and how an artwork can offer more of an experience or a situation rather than being just a visual treat or a thing to look at. I have been looking at how relationships are formed. Then I was going to Italy, and society there is often framed through a stereotype about the traditional Italian family–and of course, I was going with my family. It’s normal for me to use my own situation or biography within my work. I went from thinking about relationships [in general], to family relationships, and that really works well with how Italy is understood from the outside.

From the outside, we understand the family to be central to Italian life. Did your view of Italy, and its family life, change while you were there or has this rung true for you?

In Milan, I researched a pioneering radical psychologist called Mara Selvini Palazzoli who was a sort of maverick who tried to unwrap, or work with, relationships. She would never treat individuals, she’d get everyone to come in and see her and would treat the spaces between people. I got to understand how families work, and the habits and feedback loops and games that people play within families, whilst also thinking how pressure builds in families. In the clinic many of the cases that I looked at were fundamentally formed from the same model which is to do with what happens when the typical or traditional roles in the family are broken down by modern situations—the father loses his job and the mother goes out to work instead. The roles and structures within the families I observed, were embedded very strongly and when things didn’t adhere to this structure it caused a problem.

Your work often has a psychological element to it. Have you ever had such a direct engagement with the world of psychology?

No, I haven’t ever done anything like this at all really—done proper research and then thought about that within an art work. It was a new way of working. I normally work a lot more on instinct and guesswork. It was good to encounter what other people think too.

After laying out quite organised plans in terms of your activity, and how you’d spend your time in Italy, did you also have a clear idea of the kind of work you wanted to make or were you completely open while you were creating?

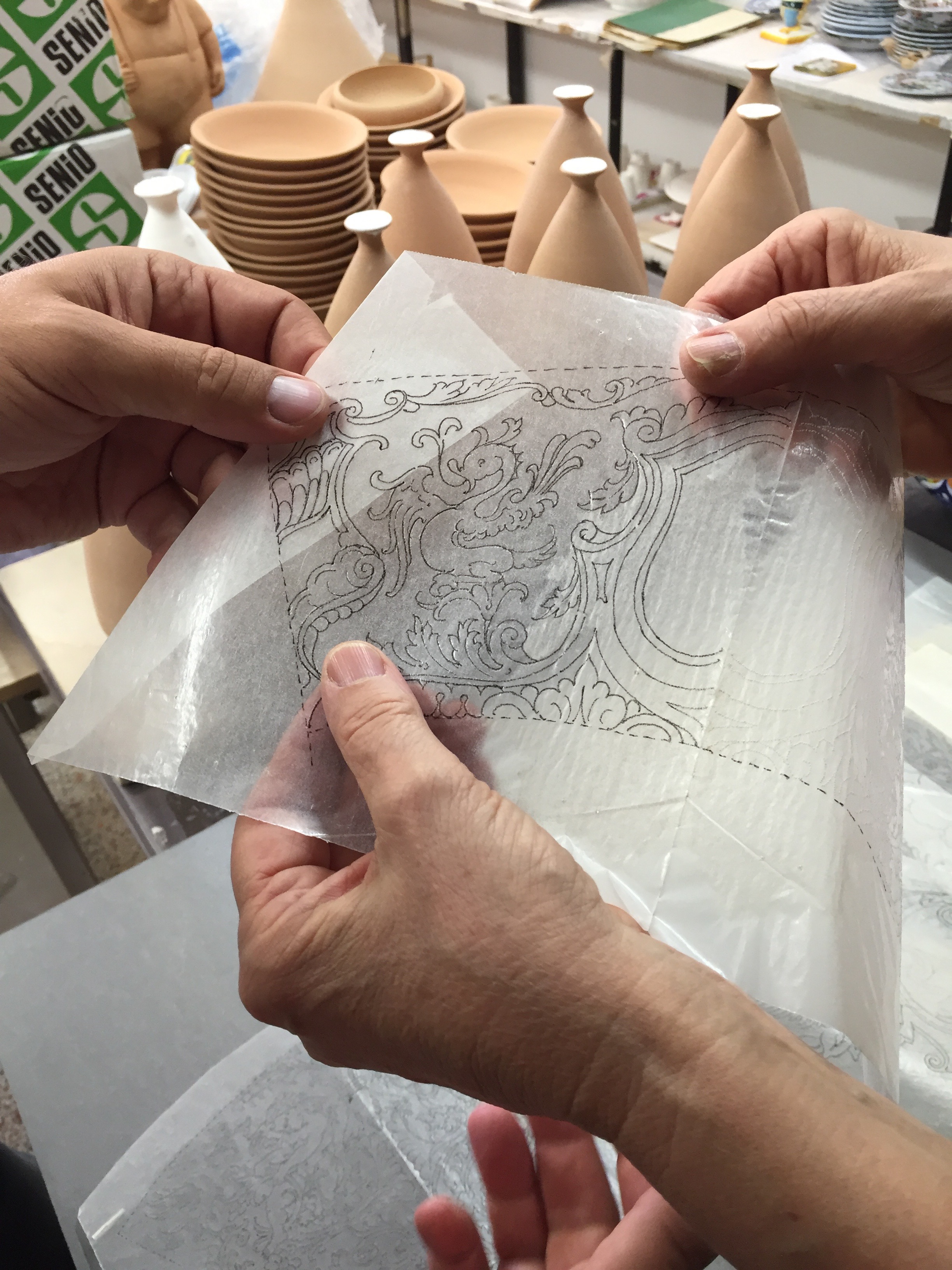

My proposal had two parts. The first was research into family relationships with a psychologist. And then I knew I wanted to do something very tactile, and my use of ceramics is completely self-taught. The second half was a much more tactile experience, learning from master crafts people about how ceramics works. The thing about maiolica [Italian tin-glazed pottery dating to the Rennsaissance], which is also part of my proposal, is that it was initially the manifestation of relationships. So for example in the 16th century if you got married you had to have a maiolica plate and if you didn’t have it, it was almost as if your wedding was inferior. So ceramic objects became a way of holding relationships. [I had] a focus on ceramics partly conceptually, and also in the studio experimenting. In the last month, I went into the full blown production of the final work.

Do you usually allow yourself such a long time to develop a body of work in this way?

I’m slow, and I always make things lots of times, so the timespan was normal for me. But in London I have a kid, I teach, it’s often chaos. In Italy, I lived opposite the Museo Carlo Zauli where I was doing my residency. I had a studio, I had the best support. It was like a dream, that way of working. I was in Faenza, it’s really calm and friendly, but at the same time, it has the best ceramics museum in the world. It was a unique situation of being in a small, tranquil place, but it’s rich. There’s so much to see and learn about.

Lots of your work is very instinctive and very physical. How do you feel the presence of such ceramic history, and also access to makers at such a high skill level, has influenced your practice?

[My work is] dumb. I want to demand a physical, raw, crude response from the viewer. I am dumb, I don’t know what I’m doing with ceramics, I’m a bull in a china shop. I was aware that the more help I got, the more technical skills I acquired, I may actually become “better” at it and that might change my work. But it was such a relief—I’ve been avoiding getting help in London, I’ve wanted to keep the work raw and crude and dumb—to have someone say to me: That’s not going to work. Rather than exhaust myself down a dead end I actually found it quite a relief, and it wasn’t a problem because the work ended up much more like it was in my head. In London, making work is just coming to terms with a series of disappointments, and the work never looking how I wanted, and the process is me coming around to the fact and saying: it is what it is. It was much better to work with people who know what they’re doing. So that’s been a bit of a red herring for me previously, that I’ve got to do it myself. I can still hold onto it being crude and dumb, but it’s going to work.

So do you feel you’ve come back feeling more in control, or in command of it?

The thing I’m doing for the show is really complicated and technically ambitious and I am actually really scared but at least I have people around me… Yes, I do feel more in control. It’s given me confidence. There’s hope!

Is feeling scared a place that you need to get to?

I think the work always knows more than me and I always have to make something to understand what I wanted to do and then make something else. I think that this residency has fundamentally helped me to be a better artist. Getting help is not a weakness. It was really good to be away from London for a few months, from the clamour of the art scene and to just do what I want to do. It’s really difficult in London to make your own vision and not be surrounded by what everyone else is doing. I don’t think many artists would admit it, but unfortunately, the art world pits you against people and, I don’t want to, but you have to think about that. I’m going to be going back [to Italy] probably once a week every month until May next year. I’m going to produce it all in Italy, so the ceramic part will be made there. It’s the most important thing I’ve ever done.

Emma Hart is the winner of the 6th Edition of the Max Mara Art Prize for Women. Her work will be shown at London’s Whitechapel Gallery later this year and then tour to Collezione Maramotti, Reggio Emilia from October 2017 to February 2018. She is currently showing at The Sunday Painter as part of Condo.