“I choose these images because they are archetypes,” van der Ende explains in the Rotterdam workshop he shares with a few other wood-carving professionals. “I want to treasure and enhance the archetype.” The wood sculptures he diligently assembles exude nostalgia—accordingly, the issue of memory often comes up in interviews. After all, some of van der Ende’s subjects are iconic Rotterdam elements: for instance, the panoramic restaurant on top of the once city-dominating Euromast observation tower, now dwarfed by Rotterdam’s increasingly spectacular skyline. “When I was a kid it was very impressive, but now it just looks small. It was built around 1960, but then a couple of years later they built a hospital that was higher, so they extended it with what they called the Space Tower.”

Born in Delft and raised in a small village, van der Ende came to Erasmus’s home town to enrol at art school when he was eighteen, and he stuck around. “I think I knew I wanted be an artist when I was thirteen or fourteen. My drawing teacher told me that to be an artist I should study to become a teacher, so I could make art and a living. But I did not believe him, and went to art academy instead. At the beginning I wanted to become a painter, but I had done that all through childhood and it just wasn’t exciting anymore. I decided to take up sculpture, which was completely new to me. Come to think of it, I’ve almost come around to painting again.”

- Fleet, 2013

- Dreadnought, 2003

It’s true, but not quite in the way one might have expected. Back in the mid-nineties van der Ende was making more traditional sculptures of submarines and ships out of wood. Before beginning work on the physical piece, he had to produce technical sketches to get the proportions right: “I had to draw the front, back, top, bottom… That’s two weeks’ work, and at the end you only have the drawings, and you still have to make it.”

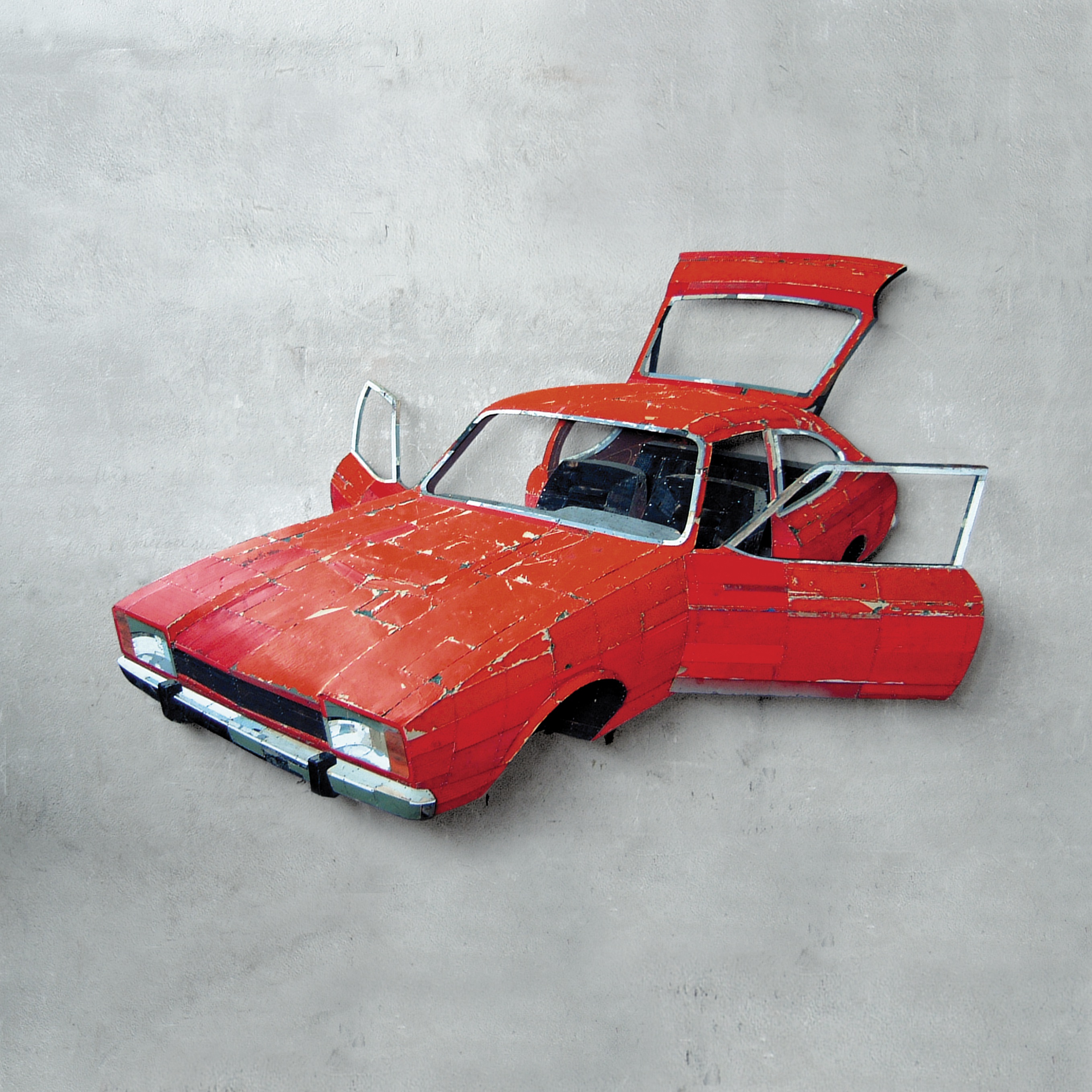

In 1998 he was the youngest artist among those invited to present a new design for upgrading Rotterdam’s Concert and Congress Gebouw de Doelen. His Mimic Diagram project, which remained in place until 2009, involved a 60 x 6 m resin board structure with a drawing computer-milled into it, to which the artist applied a web of fluorescent tube lighting to suggest the idea of a long-exposed photo of traffic. From that point onwards, full three-dimensional modelling wasn’t enough for him anymore. “I couldn’t quite translate it into other subjects. I was unable to break it open, to really be free in my themes.” Most notably, van der Ende always wanted to do cars. The De Doelen project had left him with an unfulfilled desire to take his artistic practice up a notch, and it was after a couple more experiments that the artist found his ideal medium. “I was looking for a quick, hands-on, creative way. I wanted to take the stupid work out of it. Then I had this brain wave: I could do it as a bas-relief.”

Without preliminary sketches, van der Ende can now simply download a picture from the internet, from the perspective he wants, perhaps Photoshop it, print it and start working on it. Sometimes he mocks up a small wooden or paper model and then photographs it himself. “I put it in different positions and take pictures from different angles and distances, which is very important.” The significance of the point of view is yet another painterly quality to be found in van der Ende’s sculptures, but it is not the only one.

All pieces begin with a wooden grid, a customized canvas built on top of a flat base (the part that goes against the wall and closes the “box”) to be covered with carefully selected and painstakingly assembled scraps of wood. The resulting perspective, the very striking pop-out effect, emerges from both van der Ende’s sculptural feel for volumes and his painterly sensibility for colour. He works with found pieces, so the shades that happen to be painted on the elements are part of the random challenge that makes a van der Ende artwork look so raw and authentic. “I like salvaged wood because it’s not a standard material that you buy in the store. It’s an imperfect, unexpected thing you cannot control,” he explains. “It’s a process of trial and error. I am completely dependent on what the material has to offer.”

- Vostok, 2006

- Endeavor (Apollo15), 2006

It is hard to believe that he does not use paint, and in his studio I ask him specifically about the steak piece, a seemingly juicy chunk of red meat that he immortalized van der Ende-style. He insists he put no paint on it, and adds: “Now it’s in a restaurant in New York, which means it passed the test of the connoisseur.” Ron van der Ende wants his work to be accessible to anybody, not only the art-educated. The artist is no outsider to the Rotterdam scene (he manages the long-running art blog aggregator artbbq.nl), but the autonomy of the objects he creates is of prime importance. “Realism is not the ultimate goal. I want the work to be self-evident. I always loved photography in that way. I want to be like a neutral observer.”

Such neutrality finds expression in the way the artist approaches the gallery space. Instead of indulging the site-specific installation aesthetics that would scatter the artworks in all directions, tempted by the dimension afforded by the floor, van der Ende likes instead to keep them up on the wall, each its own object, lest they become too much like props. There is an interplay between a venue’s lighting and the painted shadowing embedded in the surfaces of his sculptures, which is part of the game. And so is the sometimes disorienting gap between an object’s position within the gallery space and the perspective of the original image. Such visual short-circuiting is especially evident in ZZ, a work comprising several objects originally photographed from different angles. “They are in a group but they all come from a different photo, so each has its own space.”

“Realism is not the ultimate goal. I want the work to be self-evident. I always loved photography in that way. I want to be like a neutral observer”

Van der Ende now wants to create landscapes. He made a piece depicting an aerial view of Yosemite Park in 2013, but his intention is to do things differently next time. “I really want to find a way to make a cut out of the landscape, so that it will probably have two vertical lines and a horizontal line on the bottom, and then only the top would be a free shape. I would look to things that relate to the human landscape, like mountain passes, for example, the lowest place where you can pass to the other side. That would be a very basic orientation point for humans, like a very old common memory that is built into our brain.”

Talking about memories and lasting connections, I ask him something I had been thinking about since I read that, despite all the vehicles in his artworks, he has never got his driver’s licence: are the two things connected? “I don’t know. I don’t think there is really a connection. I’m just too absorbed in my work. I never got around to it.”