In 1928, Virginia Woolf delivered a speech at the University of Cambridge about the barriers which prevent women from realizing their creative potential. In A Room of One’s Own, published a year later and now a canonical feminist text, Woolf argues that part of what holds women back is a lack of precedent. She encourages women to correct this by creating their own artistic tradition and history. Almost a century after Woolf’s passionate address, the art world seems to finally be responding to her call.

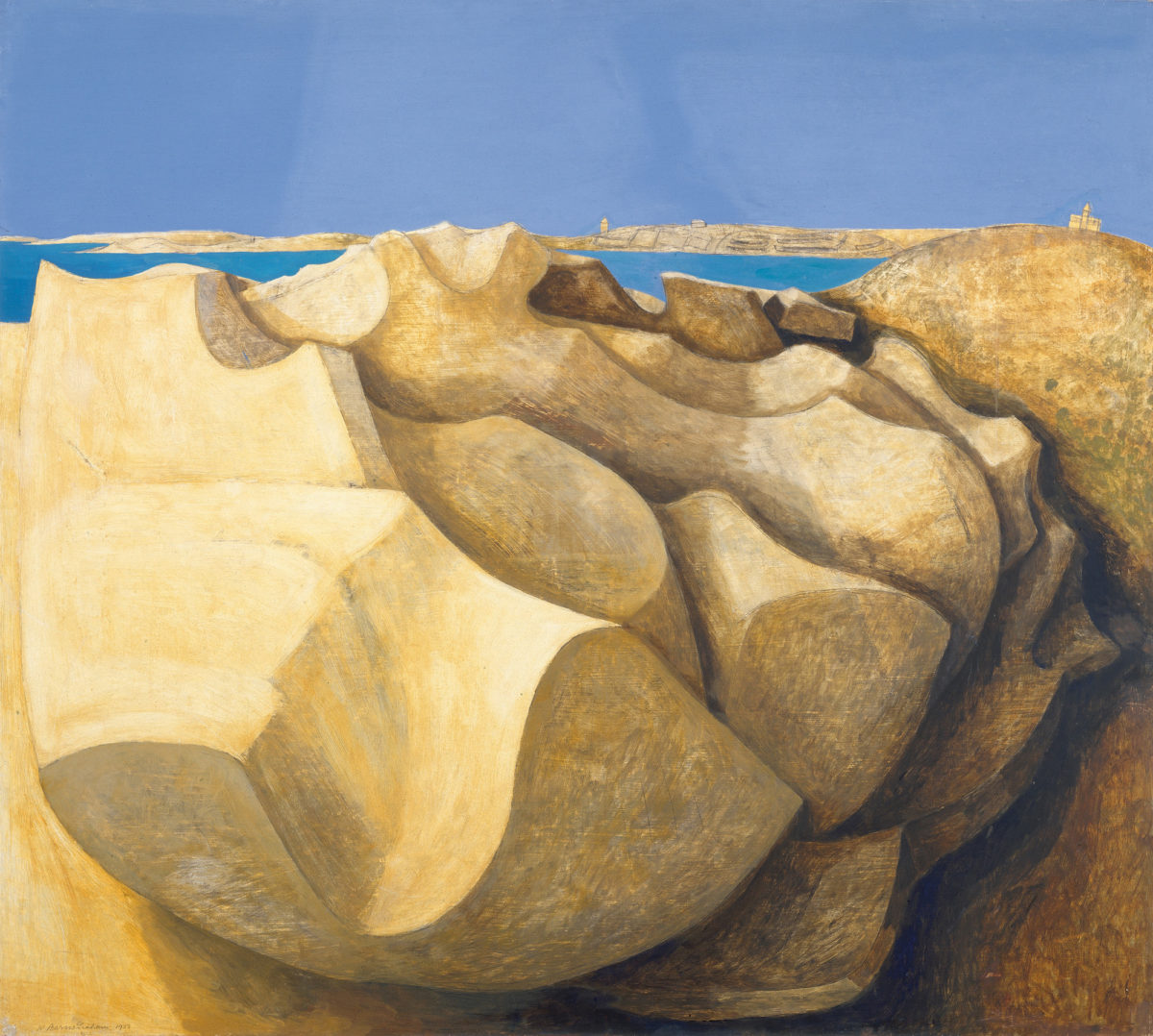

In the last few years, all-women exhibitions, in both public museums and commercial galleries, have become de rigueur: from The Photographer’s Gallery‘s Feminist Avant-Garde of the 1970s and Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery’s Women Power Protest to the White Cube’s Dreamers Awake and Hauser & Wirth Somerset’s Unconscious Landscape.

Even Frieze London has joined the party, staging all-women sections of the fair, with Sex Work in 2017 and Social Work in 2018.

But, although these exhibitions and displays help to increase the representation of women artists, they are not without their issues. By using the gender of the artists as the primary selecting criterion, they risk putting forward a limited view of gender identity and suggesting that art by women is somehow inherently different or separate to art by men.

“By using the gender of the artists as the primary selecting criterion, they risk putting forward a limited view of gender identity”

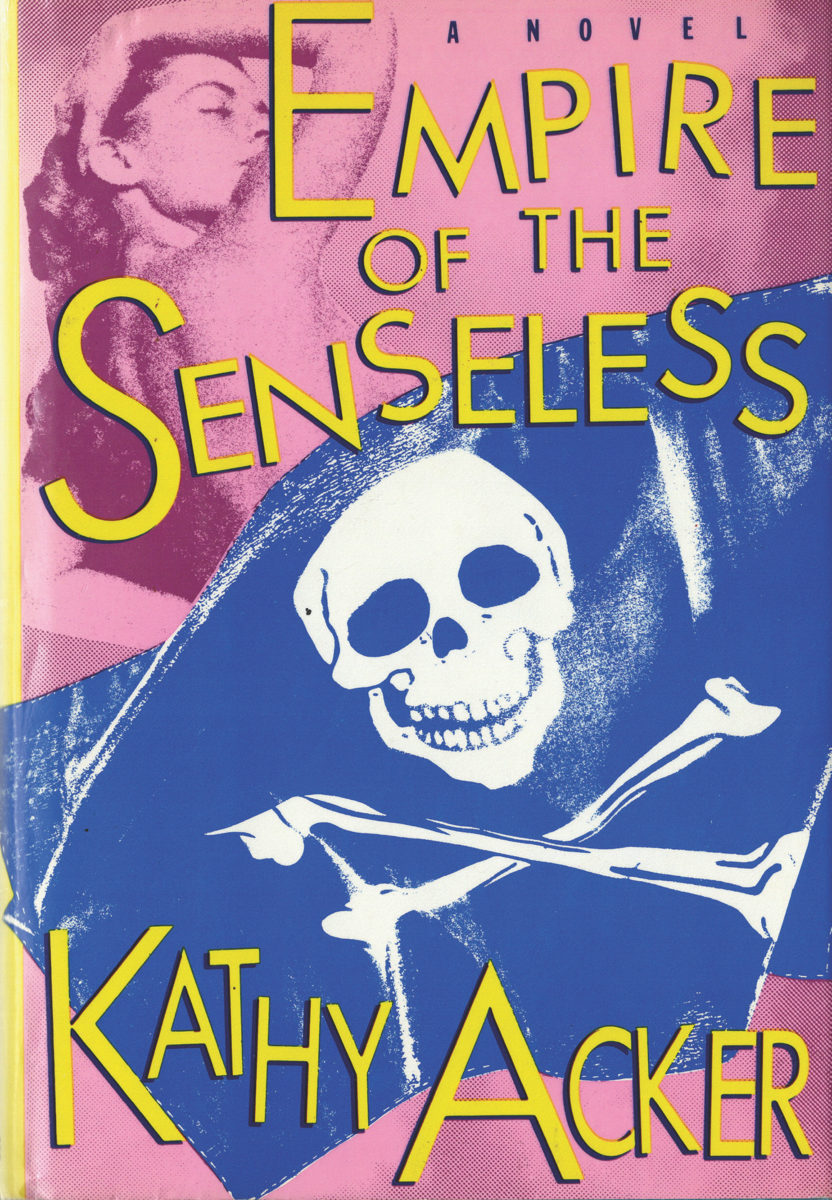

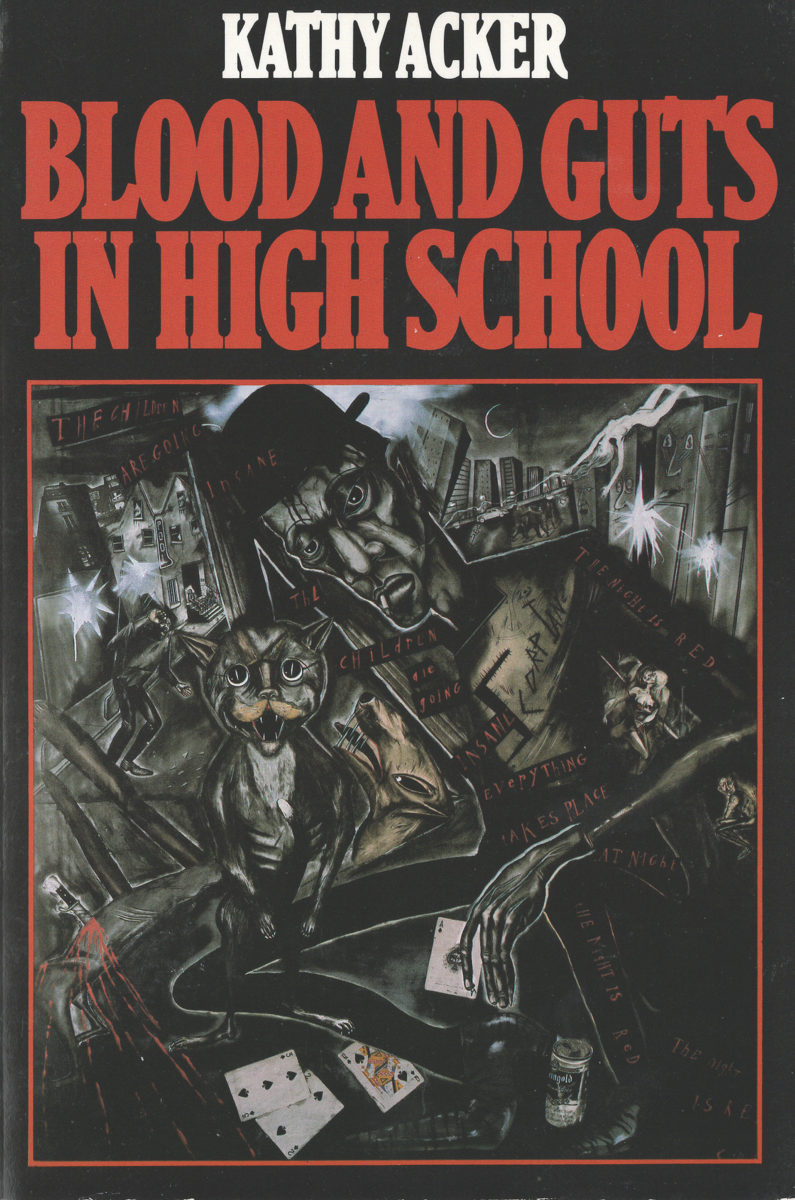

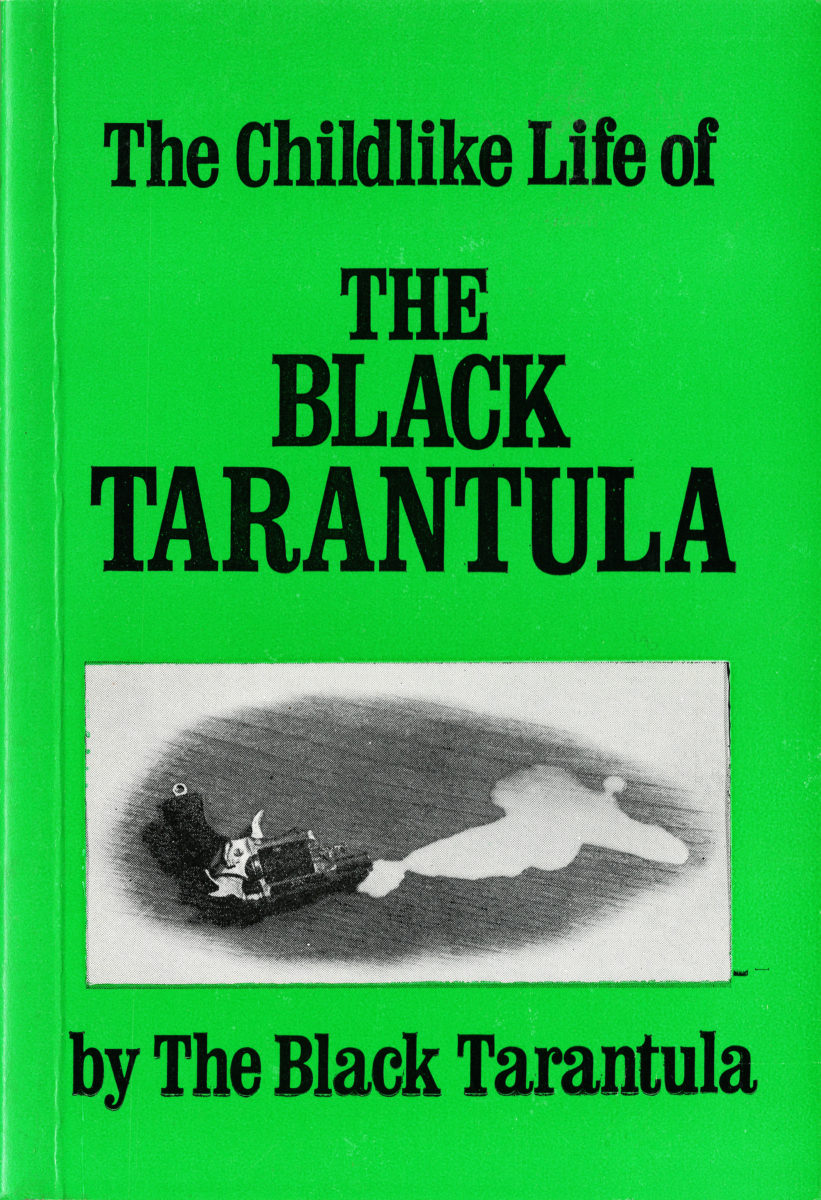

Two recent exhibitions, however, have pioneered a new model of feminist exhibition-making, in which gender is often the subject matter of artworks, but not the basis of selection for their creators. Take last year’s exhibition Virginia Woolf: An Exhibition Inspired by Her Writings, which opened at Tate St Ives, before touring to Pallant House in Chichester and the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. With the current ICA show, I, I, I, I, I, I, I, Kathy Acker, both take the literary oeuvres of two feminist icons as a starting point and show their influence, direct or indirect, on visual artists over the decades.

Woolf and Acker came from different worlds: Woolf grew up in Victorian London and Acker in post-war New York. In many ways, though, the two were soul sisters. Both rebelled against the privilege which they were born into and opted for a bohemian lifestyle of creativity and polyamory. Both were prolific writers, penning dozens of works of fiction, as well non-fiction and hybrids of the two. Crucially, they had a similar approach to gender, as something which is fluid and ever-shifting.

Woolf’s most prolonged depiction of gender is her 1928 novel Orlando

(1928), a mock-biography of, and love letter to, her fellow writer Vita Sackville West. It follows a character whose lifetime spans from the 1580s until 1928, and who wakes up one morning having undergone a mysterious change of sex. After this gender transformation, the “biographer” goes on to discuss the idea of an androgynous mind: “Different though the sexes are, they intermix.”

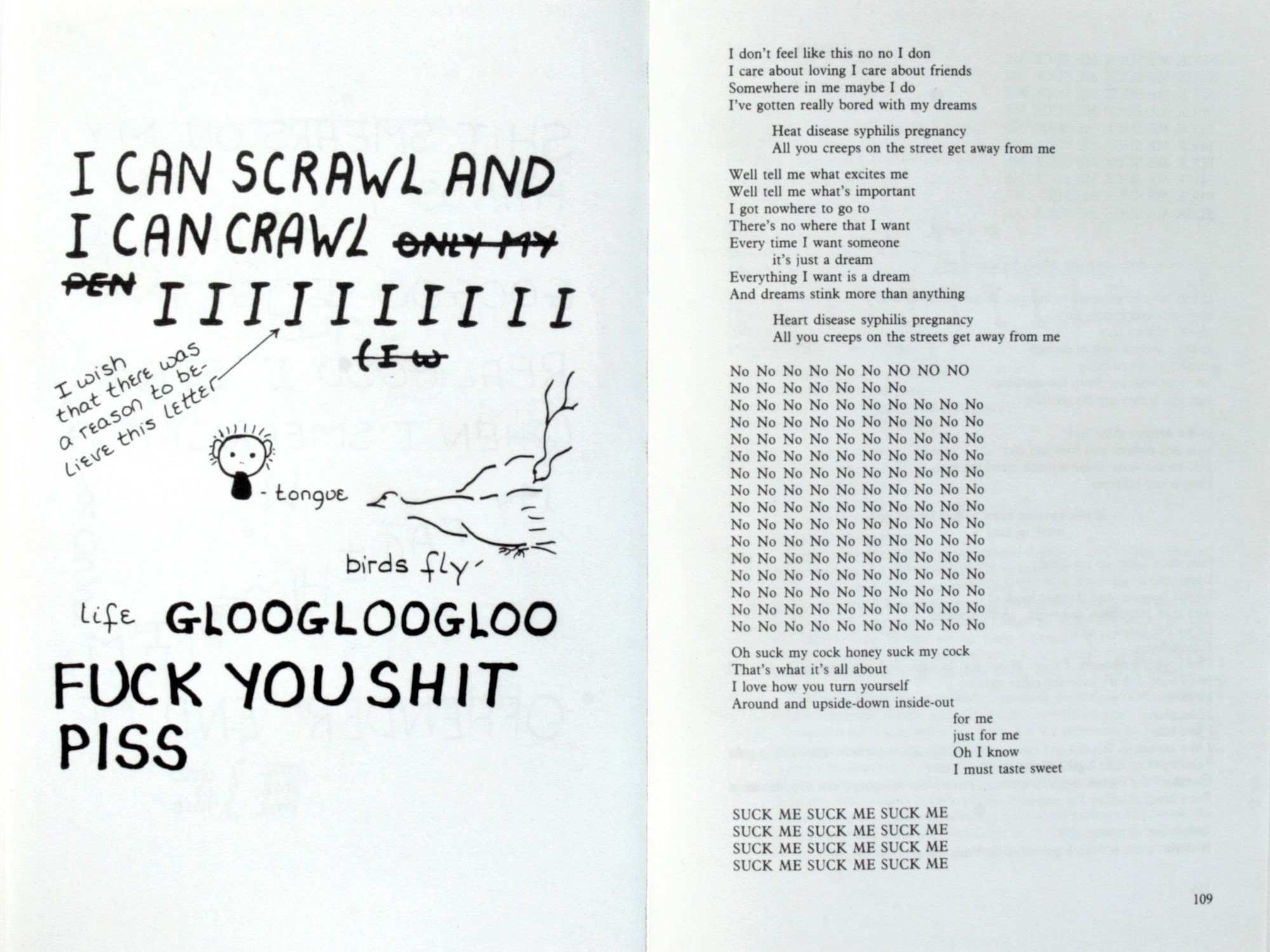

A similar transcendence of gender and time occurs in an autofictional piece by Acker, printed on one of the walls of the ICA’s exhibition. One moment it’s 1985 and “my mother (in-law) makes sure I’m forever imprisoned in jail”. The next it’s 1789 and “on account of my pro-Revolutionary attitude, they move me from my prison at Vincennes”. “I” has morphed from a youthful, female Kathy Acker to a middle-aged, male Marquis de Sade.

As the exhibition’s title—I, I, I, I, I, I, I, Kathy Acker—suggests, Acker’s “I” is always multiple. So is Woolf’s. In her Cambridge address, she speaks through an “I” who is, and also is not, herself. It makes sense, then, that the exhibitions explore how these myriad literary “I”s have been reflected in works of visual art, and how Woolf and Acker’s works have metamorphosed across art forms.

“Crucially, Woolf and Acker had a similar approach to gender, as something which is fluid and ever-shifting”

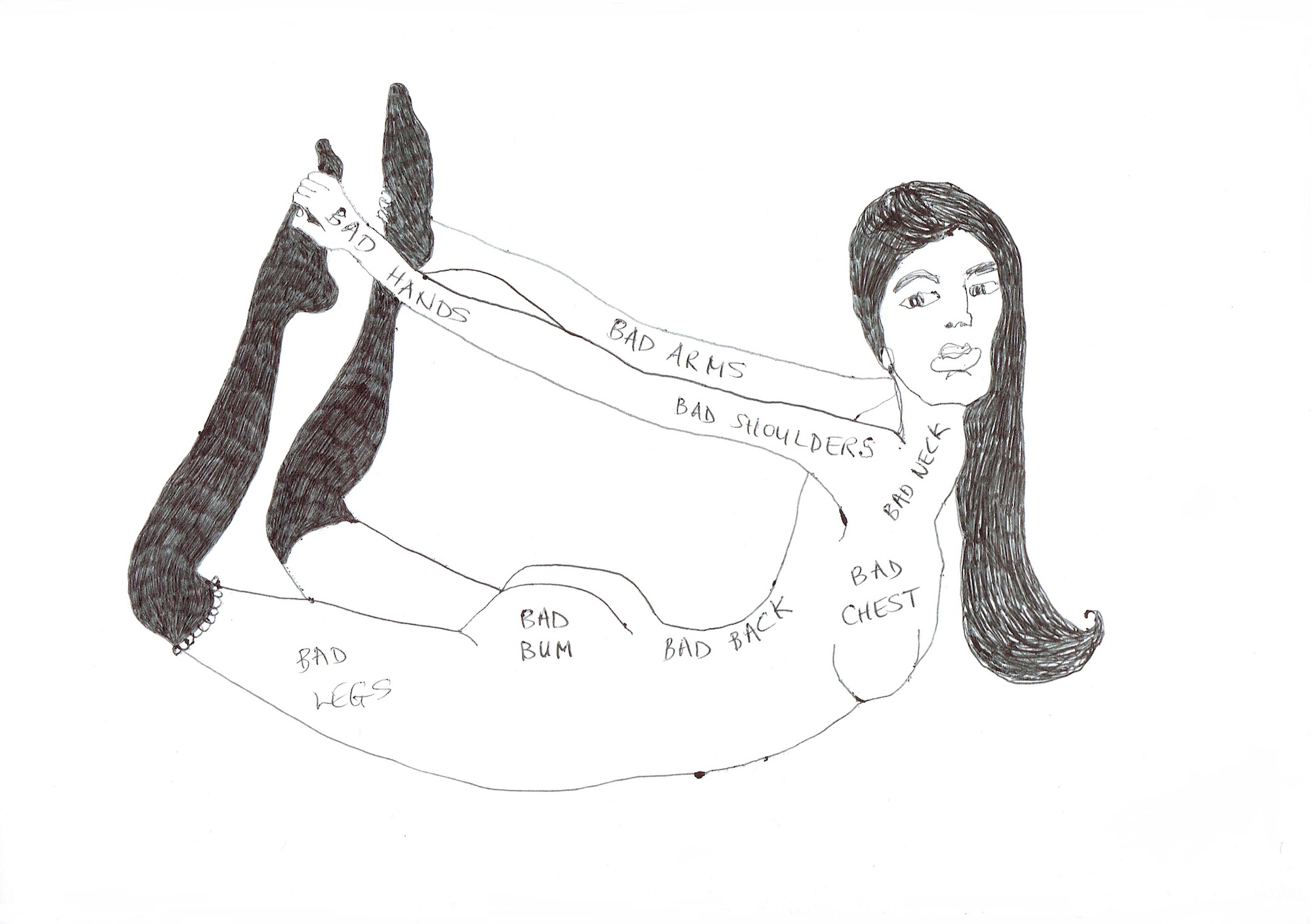

These exhibitions weave and wind, they have no real beginning or end, and certainly no singular narrative. An entire wall at the ICA is covered with a supergraphic of Acker’s bibliography, the colourful book covers joined by wavy, crimped, dotted and doubled lines. In Woolf’s show, multiple walls are wreathed with drawings of fanciful female nudes by the painter France-Lise McGurn. Works by artists contemporary to the Acker and Woolf hang alongside works by artists contemporary to us, and some in between.

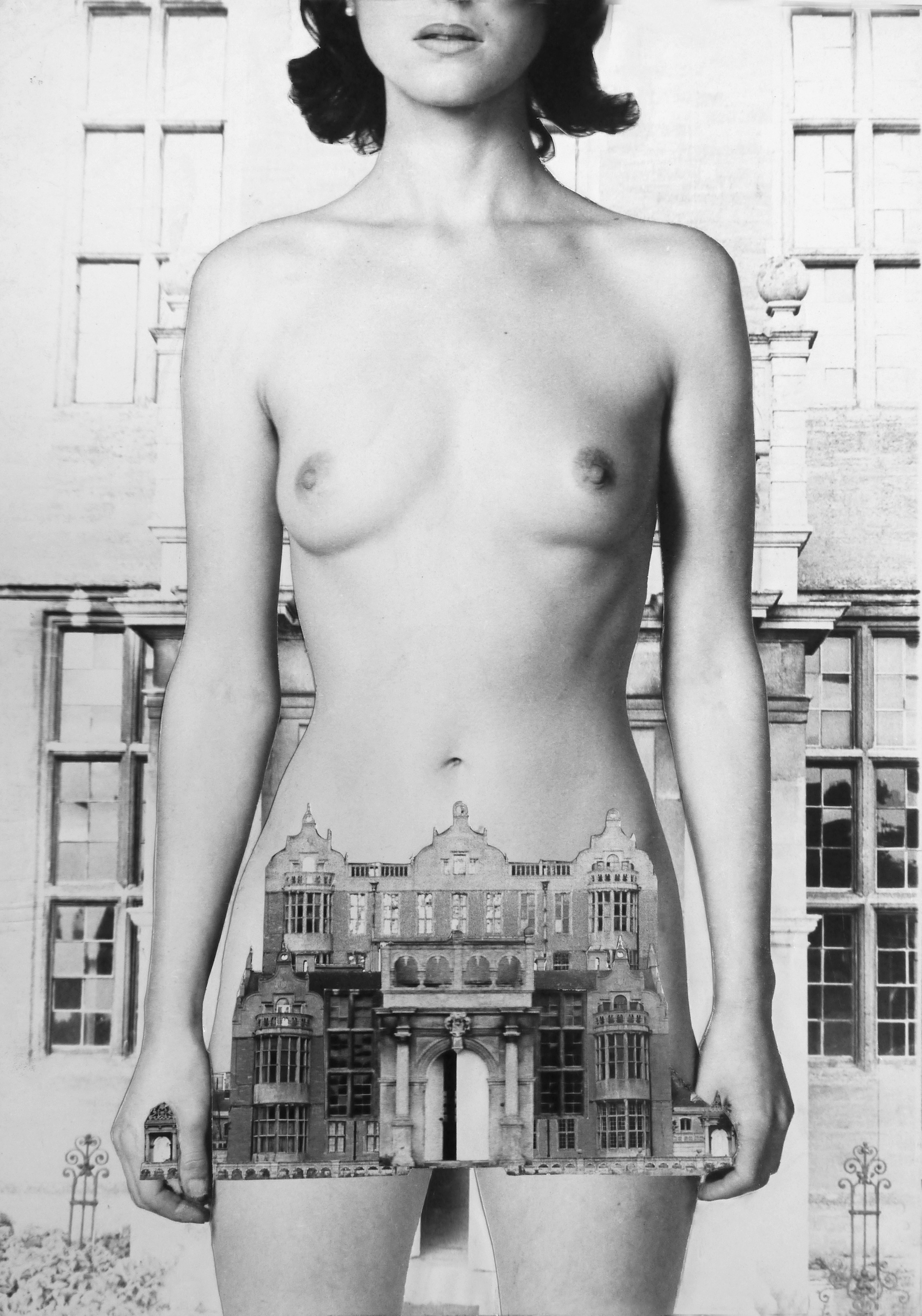

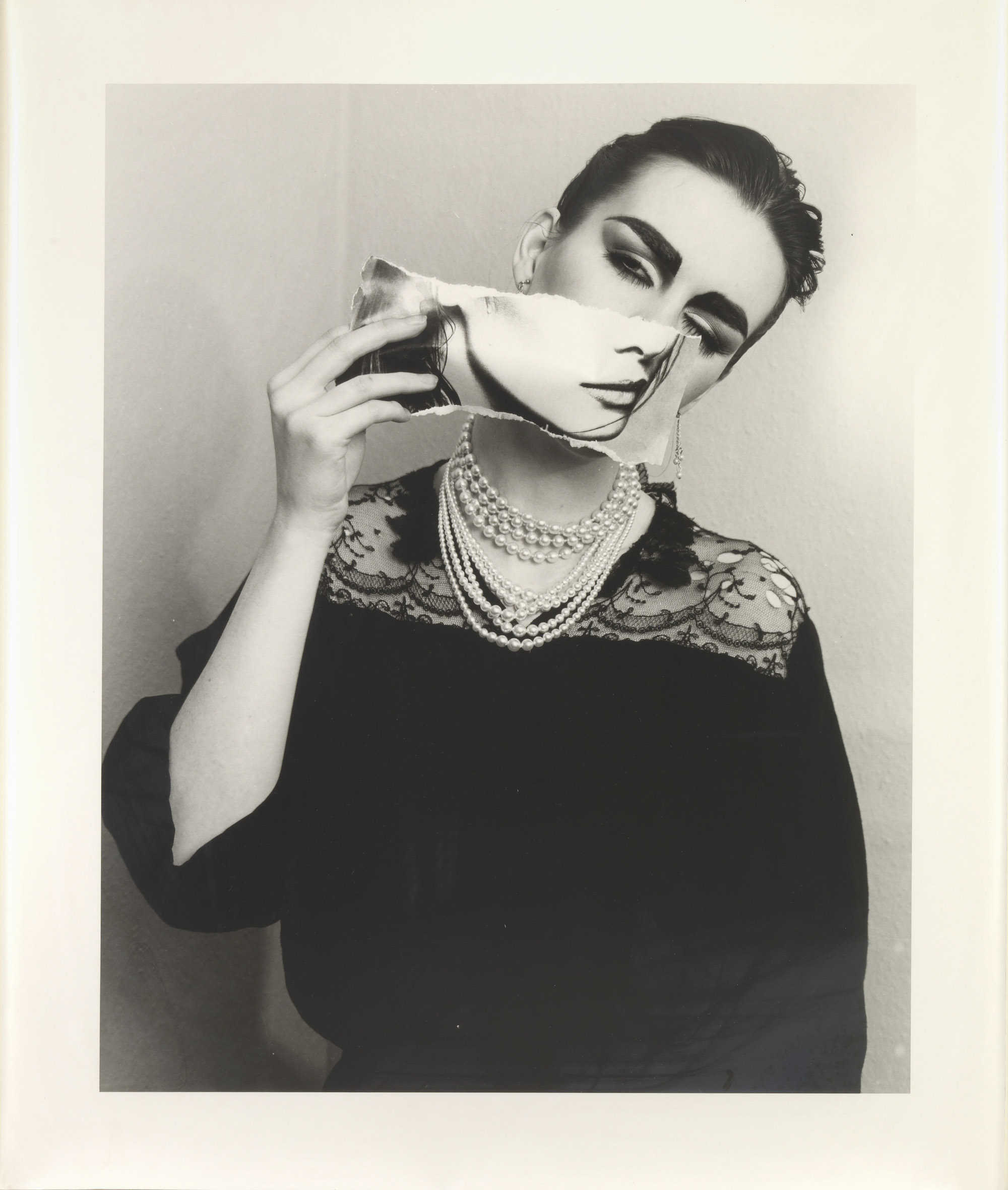

Many of the works in these exhibitions explore the feminine, masculine or androgynous self. The Woolf show includes She/She (1981), a photographic series in which the collagist Linder casts herself in a hyper-feminine style with lace-trimmed dress and multiple strings of pearls, in order to deconstruct the feminine ideal.

In her abstract assemblage from 2017, Manliness without ostentation (I learnt from what I heard and can remember of my father), Rebecca Warren mounts pink neon tubing bent into a subtly masculine form onto a plank of wood washed with a pale cream. Then there are the gender-bending self-portraits of French photographer Claude Cahun and English painter Gluck (both of whom ditched their given names and took on more gender-neutral monikers).

The first work that you encounter as you enter the Acker exhibition is a pair of photographs by the punk photographer Jimmy DeSana

. One of them—Masking tape (1979)—depicts a body mummified in masking tape, from which the only body parts which emerge are hands, feet, breasts and penis. The videos and photographs of Acker herself, which are dotted around the exhibition, show her androgynous self-presentation. A symbol of this is her Vivienne Westwood jacket, which hangs from one of the walls, a piece of clothing which is both masculine and feminine.

“Many of the works in these exhibitions explore the feminine, masculine or androgynous self”

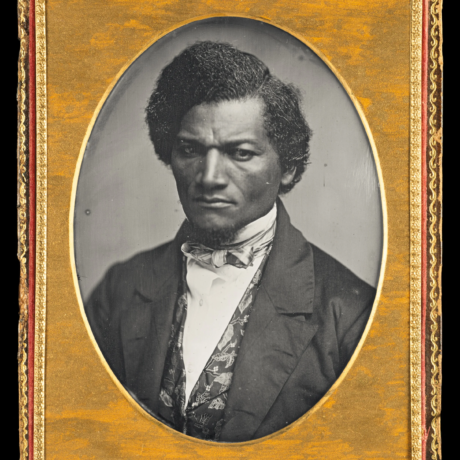

One of the artworks in the Woolf exhibition, Tradition of Elasticity and Endurance (2011) by Anna Ostoya, is a collage of black-and-white headshots of around forty avant-garde twentieth-century women artists, including Georgia O’Keeffe, Barbara Hepworth and Dora Maar. It is a literal representation of Woolf’s call for the creation of a women’s artistic tradition.

There is no perfect way to create such a thing. But these two exhibitions begin to carve out that space and, much like the writers who they are inspired by, they are experimental and open-ended in their ambitions. Where others pigeonhole, these set their subjects free.