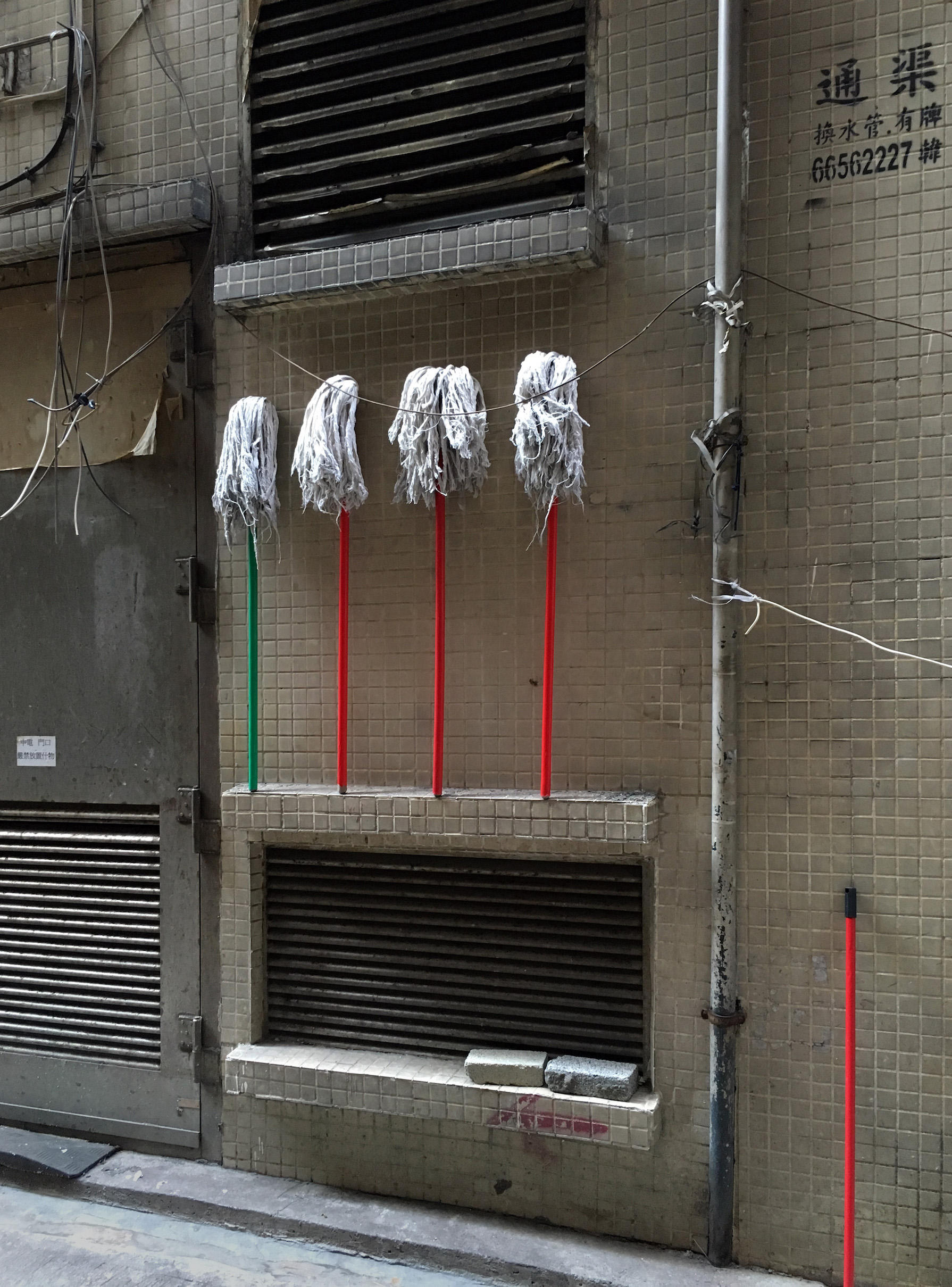

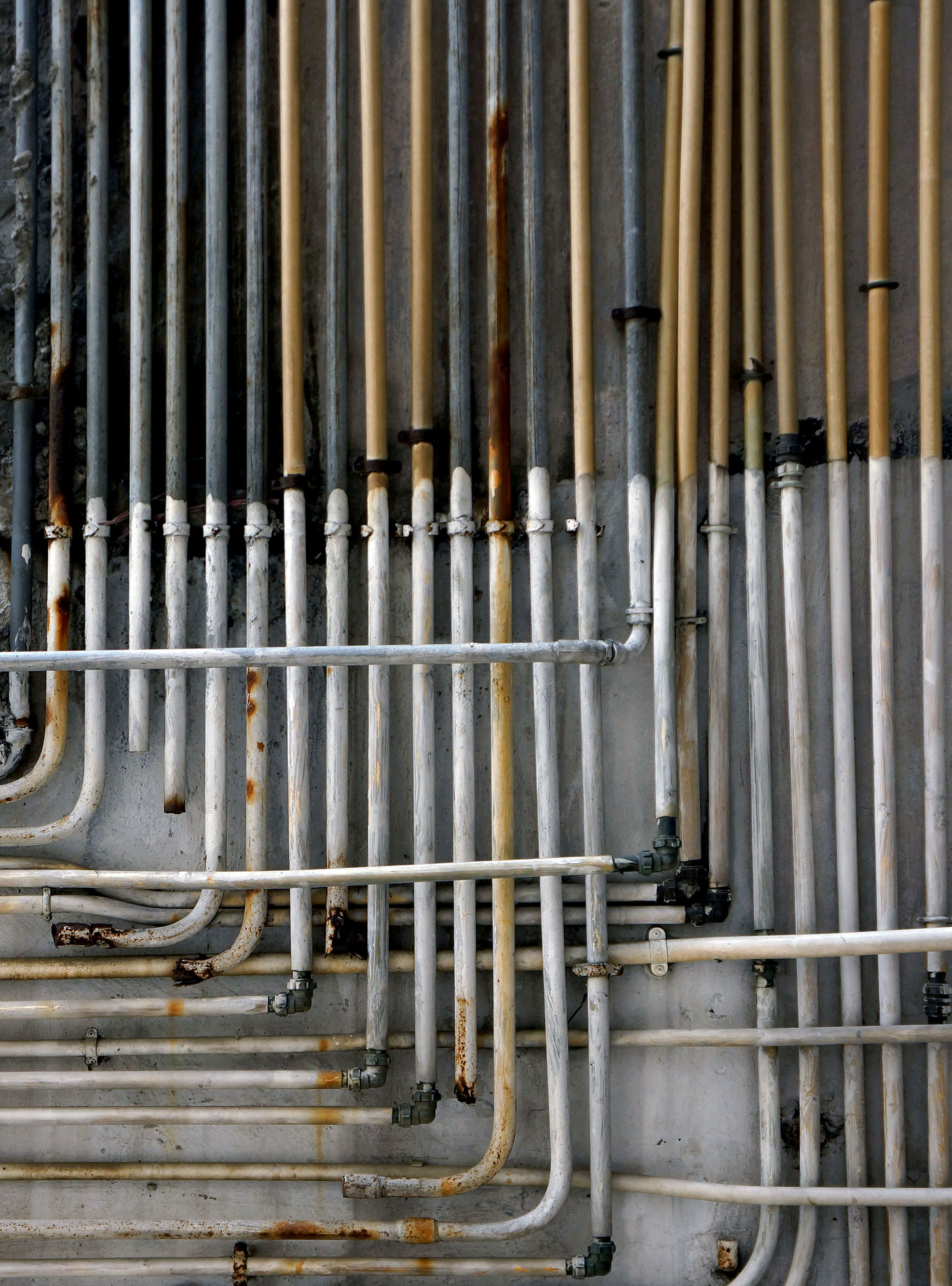

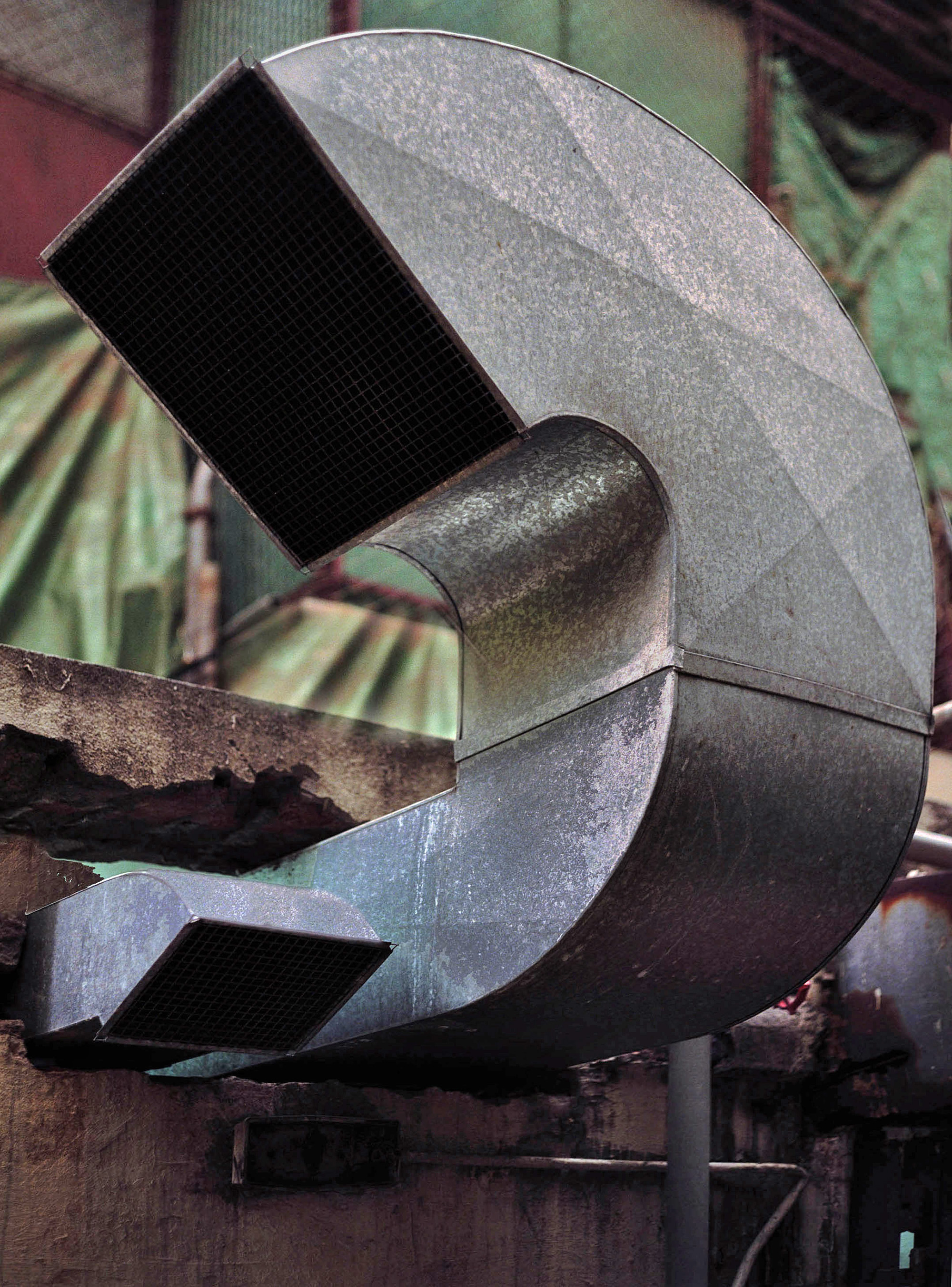

“I see myself as an anthropologist,” Michael Wolf tells me as he guides me around his show, Informal Arrangements (27 November 2015 – 9 January 2016), at Flowers Gallery in London’s East End. The densely gridded façades of Hong Kong’s high-rises dominate one wall but elsewhere the material on display has a more improvised, intimate air. As a photographer—the artist’s principal medium—Wolf has an abstracting eye, but his shots of the city’s unofficial life, taken in the back alleys where Hong Kong’s workers retire to grab a quick cigarette or hang their mops to dry exude a rich romanticism.

“It’s a bit like looking under the bed,” he says of his ongoing exploration of the city’s anonymous offstage spaces.

Although he is also the creator of signature projects made variously in Chicago, Tokyo and mainland China, Hong Kong has provided Wolf with his principal focus since his arrival in the city in 1994. That was three years before the then British colony was handed back

to the People’s Republic. His work across the decades—initially as a photojournalist for the German magazine Stern, and latterly on independent art projects—could be summarized as a celebration of the Special Administrative Region’s singularity, a quality under increasing pressure from the homogenizing policies of the mainland Chinese government. “Chinese influence is going to dilute this feeling of difference, of independence, and that’s basically my whole project—recording what makes Hong Kong different from other places. It’s an incredible record because in ten years the back alleys will be over. The government will have sanitized them.”

If Wolf is attracted to the sprawling irregularity of Hong Kong, his project serves to put some order into the disorder, or at least to find patterns in the chaos. “I don’t make a heading and then take photographs,” he explains of the typologies that structure his work—coat hangers, strings and exhausts. “I just photograph and then in the evening put them in folders and when I’m finished I might say: ‘Oh I have a folder with twenty-three plastic bags. There must be something.’ Some days I just go out and photograph plastic bags.” Plastic bags are a familiar presence in public life the developed world over, but their uses in Hong Kong are culturally distinctive. “The plastic bag is one of the most ubiquitous storage objects for working-class people there so you see bags everywhere.”

He’s always been a collector. “My mother was a hoarder. I inherited it from her.” A recent house move made him realize how much stuff he’d accumulated. “I swore to myself I wasn’t going to start again. That didn’t last very long!” he laughs. Not that he’s ever gone in for the obvious in his collections. “I like to create my own genres,” he says. Hence his Bastard Chairs, the adulterated makeshift seats of which he has more than seventy, and hence the ever-expanding list of typologies in his photographic work: umbrellas (his Hong Kong Umbrella book brilliantly documents the student protests of autumn 2014); gloves (“They have a tradition in photography. You think of Brassaï and the photographers who shot windows of glove shops. They have this surrealistic element—they’re recognizable as something human, a human hand”); even mops (“There were the interesting ways they hung them up to dry”).

Wolf never goes out without a camera. On any day in Hong Kong he might take a bus to a particular district and then continue on foot. “On a good day I’ll walk 25,000 steps. I’ll look on my phone to see how much I’ve done.” He used to be a stickler for analogue technologies but gave up on film several years ago now. He often uses his iPhone—”It has one very big drawback,” he observes, “which is that you can’t control the depth of field”—although the prints he makes are presented in a non-native format. He doesn’t care much for Instagram. “I don’t like the square format. Hong Kong is a vertical city.”

“It’s very documentary in nature and many galleries like conceptual work. But I’m rooted in the real”

The years 2003–05 were a transitional period for Wolf. He had moved to Hong Kong in the mid-1990s to work as a photojournalist, but with the new millennium and the advent of new technologies magazine budgets were being slashed and his profession was in financial retreat.

“I had had a long career as a photojournalist but knew I could no longer keep doing it in a dignified manner and in a way that would satisfy me.” Happily, a new—related—career in art seemed to be beckoning. After all, both his parents were artists.

The journey from journalism to art would prove an arduous and frustrating one, however. “I was forty-nine years old. I had never been rejected so many times. You visit people with what you think is a very nice portfolio and some don’t let you get in the door. Others say: “Oh it’s interesting. Come back next year…'”

He began to wonder whether he should change the way he worked to appeal more directly to the established tastes of gallerists. “But in the end I think I made the best decision of my life: I didn’t change anything. I had this feeling—I have a very neat way of seeing things and I’m going to stick to it. It’s very documentary in nature and many galleries like conceptual work. But I’m rooted in the real.”

One of his earliest independent art projects that was very much “rooted in the real” involved him travelling to mainland China to photograph the artists of Dafen, a village on the outskirts of Shenzen where, in the first decade of the new century, somewhere in excess of 5,000 (estimates vary) painters resided and produced sixty percent of the world’s oil paintings—most of them copies of more famous artists’ work.

The project took shape after a chance encounter with an Australian businessman at a party.

“I asked him what his business was,” Wolf remembers. “He said: ‘I sell art to Walmart.’ He was shipping three forty-foot containers a week of paintings.”

It transpired that his interlocutor ran a production line in Dafen that was churning out literally thousands of copies of masterpieces of Western art, to be sold mostly to hotels and proud new homeowners in the US. Following his photojournalistic instinct, Wolf set off for Guangdong province to witness the phenomenon—part of the Chinese “economic miracle”—for himself. In one studio in a third-floor walk-up he found “six people doing different sections of famous paintings. [With van Gogh’s Sunflowers] one would do the flowers, another would do the vase, and they’d hang them up with clothes-pins to dry.” Wolf decided to shoot a series of witty portraits of the Chinese artists alongside their copies—Hoppers, Lichtensteins, Hockneys and, inevitably, Leonardo’s Mona Lisa. “Because the prices of the originals were going through the roof at auction I decided to make a comment on the copies,” Wolf explains. In the book version of the project, Real Fake Art, published in 2011, opposite each portrait Wolf printed the price of the copy. Van Gogh’s Sunflowers, for instance, fetched $7. “The price was based on size of canvas and amount of paint used,” he says.

Real Fake Art has proved to be one of the defining photobooks of the past decade but the project wasn’t met with immediate success—Wolf encountered resistance to his photojournalistic practices, notably in his native Germany, where he had a meeting with museum curators in the hope of having the images exhibited there. It seemed to go well. “These have to be shown here!” his hosts told him enthusiastically. “But two months later I received an email: ‘Dear Michael, I’m so sorry…'” The problem was apparently that Wolf had studied at the Folkwangschule in Essen rather than at the Kunstakademie in Düsseldorf, where leading German art photographers such as Andreas Gursky and Candida Höfer did their diplomas. “Wrong school!” the powers-that-be had declared. “Had I studied in Düsseldorf, they would have exhibited the work,” Wolf explains. “But because I went to a photojournalist school, I couldn’t be an artist.”

“Had I studied in Düsseldorf, they would have exhibited the work. But because I went to a photojournalist school, I couldn’t be an artist”

Another of Wolf’s most celebrated projects that is also notably rooted in the real is Tokyo Compression, a series of magnificently expressive portraits of Tokyo workers wearily pressed against the windows of commuter trains—images of a latter-day Dantesque outer circle of hell.

The commuters weren’t necessarily keen to be snapped. “They couldn’t do anything because they were immobilized like sardines,” he says of the subjects of these curiously intimate shots. “Most art photographers would have had to stage it somehow—buy half a train and put the people in there. It’s quite daunting to go there every day and confront commuters who don’t want to be observed by the camera. It’s something that I learned as a photojournalist: you don’t come back with nothing. If you do, you lose your job. So you figure out a way to do it.”

“It’s something that I learned as a photojournalist: you don’t come back with nothing. If you do, you lose your job. So you figure out a way to do it”

As a result of changes to the Tokyo commuter network, the project couldn’t be repeated now. “It’s over,” Wolf says, not for the first or last time today.

Wolf is a veteran of many self-initiated book projects. But unlike many of the younger generation of post-photographers, he isn’t a fan of Publish On Demand (pod) technology with its DIY, you-can-reach-anyone-in-the-world-via-the-web philosophy. “You need a publisher with some form of distribution,” he says. “And I need the collaboration. It’s so great when people come up with an idea about how to present something.”

Most of his work is published by Peperoni Books. “It’s worth so much to have a publisher who’s a friend,” he says warmly. “I can call at three in the morning and say: ‘Hannes, I have this idea for a new Hong Kong book. It’s called Rubber Boots and Shoes.’ And he’ll say: ‘OK, send me the folder and we can work at it.’ And that’s exactly what I did just before I came here. I just decided on another category because there are so many rubber boots and shoes in Hong Kong. We’ll play a bit of pdf ping-pong on the weekends when he has a bit of time, and we’ll do fifteen to twenty-five versions. His brother has a printing press so we do 600 copies and when they sell out we do another 400.” Wolf’s books have become highly collectable.

Though he made his reputation as a photographer, Wolf is expanding his practice and exploring fresh media and materials in his shows. In addition to the raft of Bastard Chairs at the far end of the downstairs space at Flowers, there’s an assemblage of objects in the streetfront window as you approach the gallery.

And then there are his experiments with moving-image work, shot on an iPhone and shown on small individual screens at the front of the gallery. “I’d started feeling that I was coming to the end of back alleys photographically. I still go out and I always will but I can only improve incrementally—I have an archive of 5,000 images and if I find one more it’s just a micro-percentage,” he explains. “So I had to figure out a way of representing it which was new to me and that could convey different information. [That was when] I started recognizing interesting back-alley objects which moved.”

So Wolf’s remarkable record of Hong Kong singularity continues to grow in scale and ambition, although he’s anxious that his decades-long romance with the city can’t last much longer. “In five to ten years from now,” he concludes, “in the sense of what I loved there, what fascinated me so—this sort of chaos, improvisation, patina—it will be over.”

All images © the artist; courtesy Flowers Gallery

This feature originally appeared in issue 26

BUY ISSUE 26