The Los Angeles-based artist has always been interested in materials that lend themselves to immediacy and scale—while best-known for her ceramic sculptures, a painting show at Salon 94 and a forthcoming book of her early graffiti work show just how deep this pursuit runs.

Sculptor Ruby Neri has always been a painter, too. It is immediacy, a quick route to realizing ideas, that dictates her choice of mediums rather than a strict adherence to any box. While her sculptures are instantly recognizable—ceramic vessels with human forms airbrushed in neon colors atop raw surfaces—her works on canvas are more varied. Pastels, her “dust paintings” that incorporate dry clay and oil paint, and acrylic paintings.

For the last two decades, the Los Angeles-based artist’s practice has coalesced around ceramics. It is what she is best-known for, what takes up the most space in her studio, and what she refers to as “a tree in the middle of it all.”

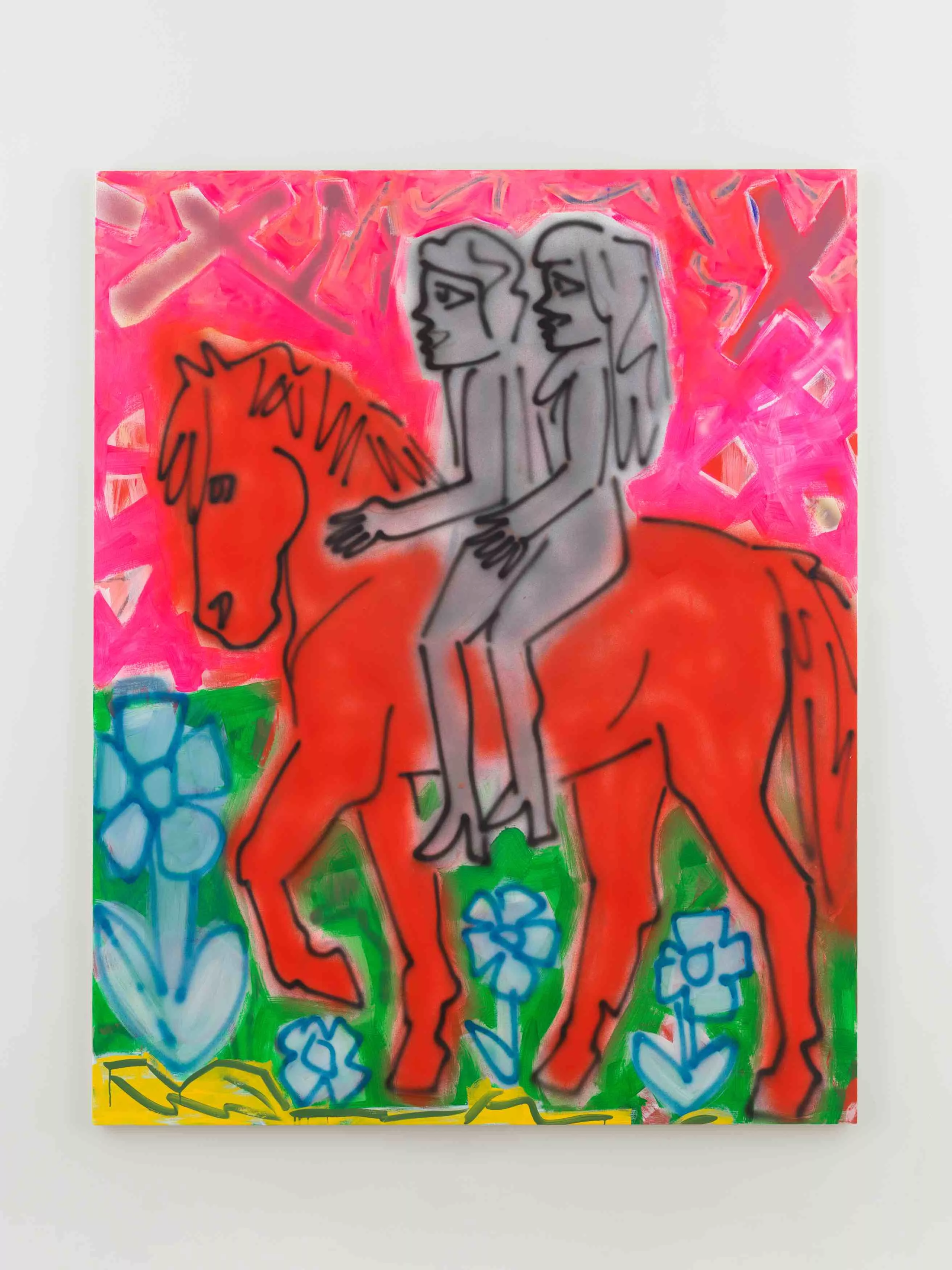

At Salon 94 in New York, her paintings have been culled from the periphery and, for the first time, placed front and center. In Love Match, 2024, two greyscale women ride a fire hydrant-red red horse atop a grassy field dotted with bright blue flowers and framed by a hot-pink sky. The atmosphere is exuberant and light, as if the subjects would blend into painterly abstraction were they not crisply outlined.

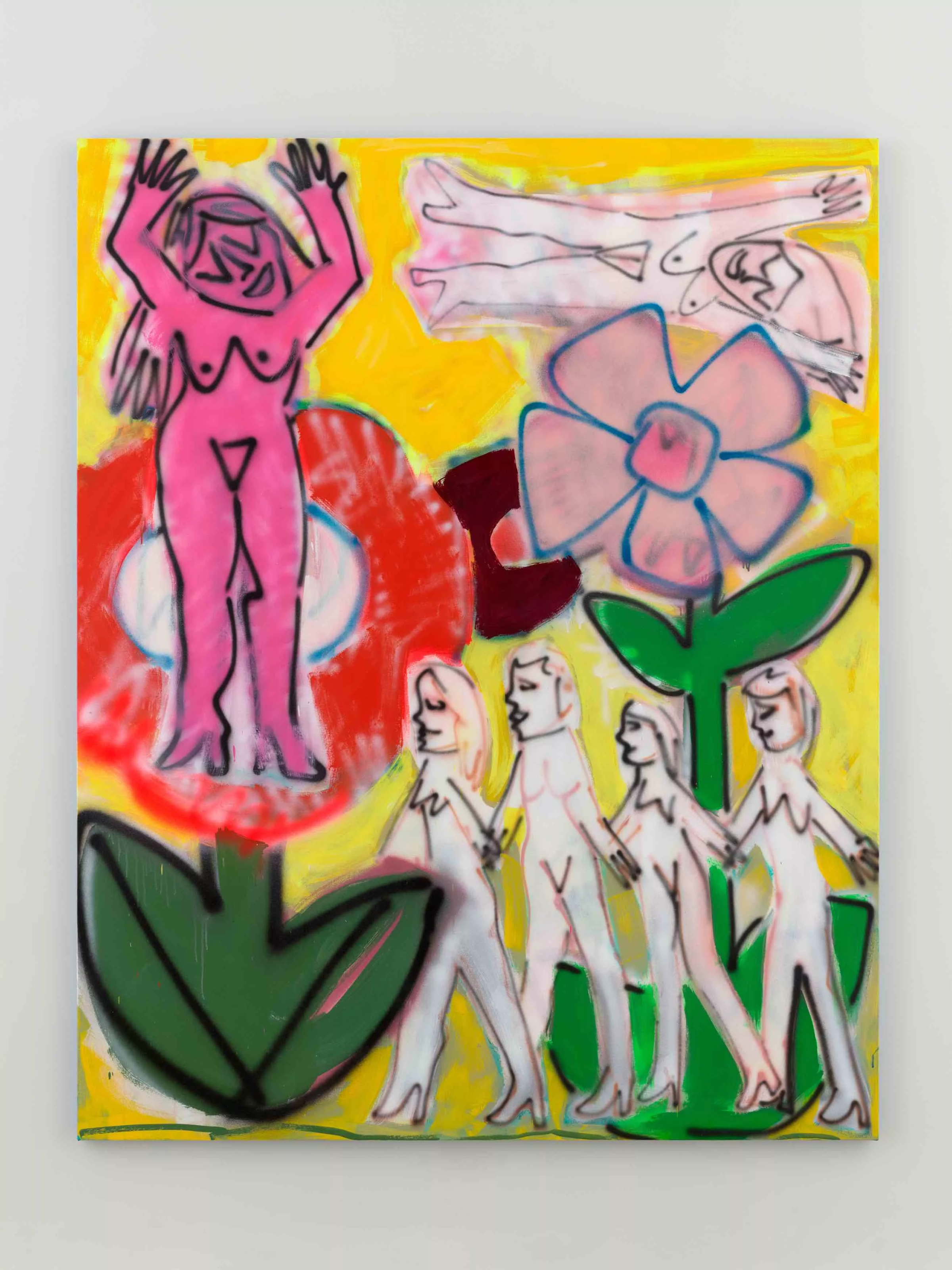

A conversation around her painting seems long overdue, but why now? Well, for starters, it is summer, and the opportunity was first suggested to Neri by the gallery. (Her last show at Salon 94 also included paintings, but it wasn’t framed around them as overtly). “We’re in such a dark time right now, and I just wanted to make something that was light and easy for me, psychologically,” Neri explains of the spontaneous and energetic works in which horses and nude women with their arms joyfully raised in the sky are set against backdrops of flowers and neon colors. “I wanted something that was bright or optimistic.” Also, she has been reflecting more than usual in preparation for a book titled REMINISCE San Francisco 1992-1996, about her lesser-known yet incredibly prolific early graffiti years in San Francisco set to come out later this fall.

The book’s title riffs off of her graffiti name “Reminisce”—which she would tag alongside images of horses in motion. “I already knew that it was going to be in my past at some point,” she reflects of the self-aware moniker. Now, years later, the content, culled over a thousand images from a handful of years, presents a time capsule of a cultural moment in the Bay Area where Neri’s peers like Barry McGee, Craig Costello, and Margaret Kilgallen, who became widely known as the Mission School, were bringing their graffiti in from the streets and into the studio, and vice versa. “Interacting with the city was almost like a performance,” says Neri. It was a social practice, more freeing and less formal than her studio practice. “When you paint on the street, you can do whatever the hell you want because it’s illegal. It’s like this weird canvas right in front of you. It’s like this personal freedom.”

Late nights at the San Francisco Art Institute’s 24-hour studio or at dive bars in the Mission would spill over into the city sidewalk, carrying a bucket and a brush. “We would be doing graffiti all the way home,” says Neri. “It was like a conversation amongst us,” she adds. “It felt like letters that we were writing to each other, notes in-between a really small group of people.” And Costello, a photographer and Neri’s then-partner, was there to document a majority of it before the paint dried; what he missed was filled in by the other artists who also archived their own work. “Traditionally, all graffiti writers go out the next day in the morning and you have to take a picture because it’s gonna be gone so fast,” says Neri. “There’s no proof otherwise that you did it… You want to prove that you were there.”

So here we are, decades in the future from this fertile time and on the dawn of its re-emergence. Look closely, and this social and temporal medium takes sculptural form: Are the walls that were dilapidated or brick or layered in wheat paste not natural readymades? Does the work end with the sprayed lines, or does it continue into the contours of the building on which it is scrawled, transforming and illuminating the structure in a new, aesthetic light. After all, while some of Neri’s sculptures are woman-shaped, others are more abstract (slabs of clay on the wall, gigantic vases).

Her father the sculptor Manuel Neri was a major figure of the Bay Area art scene (a part of the Beat Generation and Bay Area Figurative Movement), while her mother Susan Neri was a graphic designer and artist in her own right. “I didn’t want to be compared to my dad in any way, so I just painted,” she says. Graffiti, too, was a way to rebel and find her own path forward, a path that led her back to sculpture in the end.

When Neri set out on her own to attend UCLA’s MFA program in 1996 when she was 25, she immediately began making objects—at first mixed-media, then in the early aughts, the steel and plaster and fiberglass fell to the wayside and only ceramic remained. “I work better with materials that are really immediate. I need things that I can pick up and I can sort of conceptualize as I go,” she says of her gravitation towards clay. Soon, in search of a transparent paint, she picked up the spray gun once more. Yet as her sculpture practice grew, Neri continued to paint in her studio. “It is all in the cloud around the ceramics,” she says.

The horses in her new paintings recall the horses that she sprayed on walls in the middle of the night, recall the horses that she rode as a child and later as a summer job in Marin County. The large size of the animal also might be the first time Neri realized her fascination with large scales. Now, their impact can be seen everywhere from the super-sized ceramic women to the horses that materialize again and again in her paintings. At Salon 94, this is front-and-center. “I did these acrylic works to have a conversation with the ceramics in a different way,” adds Neri, citing the use of sprayed lines. “I wanted to reference how I spray the glaze on the ceramics.”

While the many connections between ceramics and graffiti may be lost on some, for Neri—who sees the clay as “a surface or an object to react against”—it is obvious. “The paintings that I just made came from me thinking about that,” she shares.

Words by Meka Boyle