American artist Sadie Benning left school at sixteen because of bullying about their sexuality. Next, using a kid’s Fischer-Price camera given to the artist by their father, Benning started making art at home. Part diary entry, part moving collage, part recording of the artist head-banging to Riot Grrrl music and posing as the film star Matt Dillon, Benning’s early films served up a lo-fi middle finger to heteronormativity, and provided an object lesson in gender-defiant cool for decades to come. In 1993, aged just nineteen, Benning was the youngest person to ever participate in the Whitney Biennial. Fast forward a quarter of a century, and Benning’s solo exhibition Sleep Rock has opened at Camden Arts Centre in London. I walk through the doors with a question on my mind. How has the queer teenage prodigy grown-up?

“F”

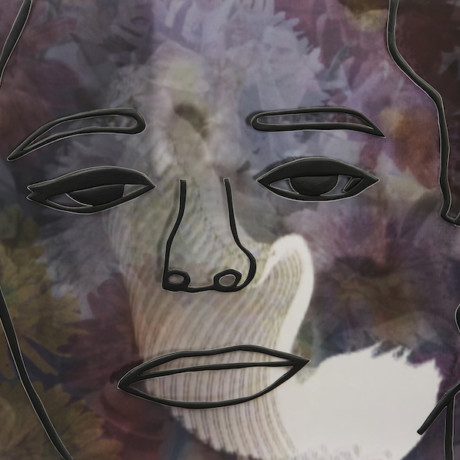

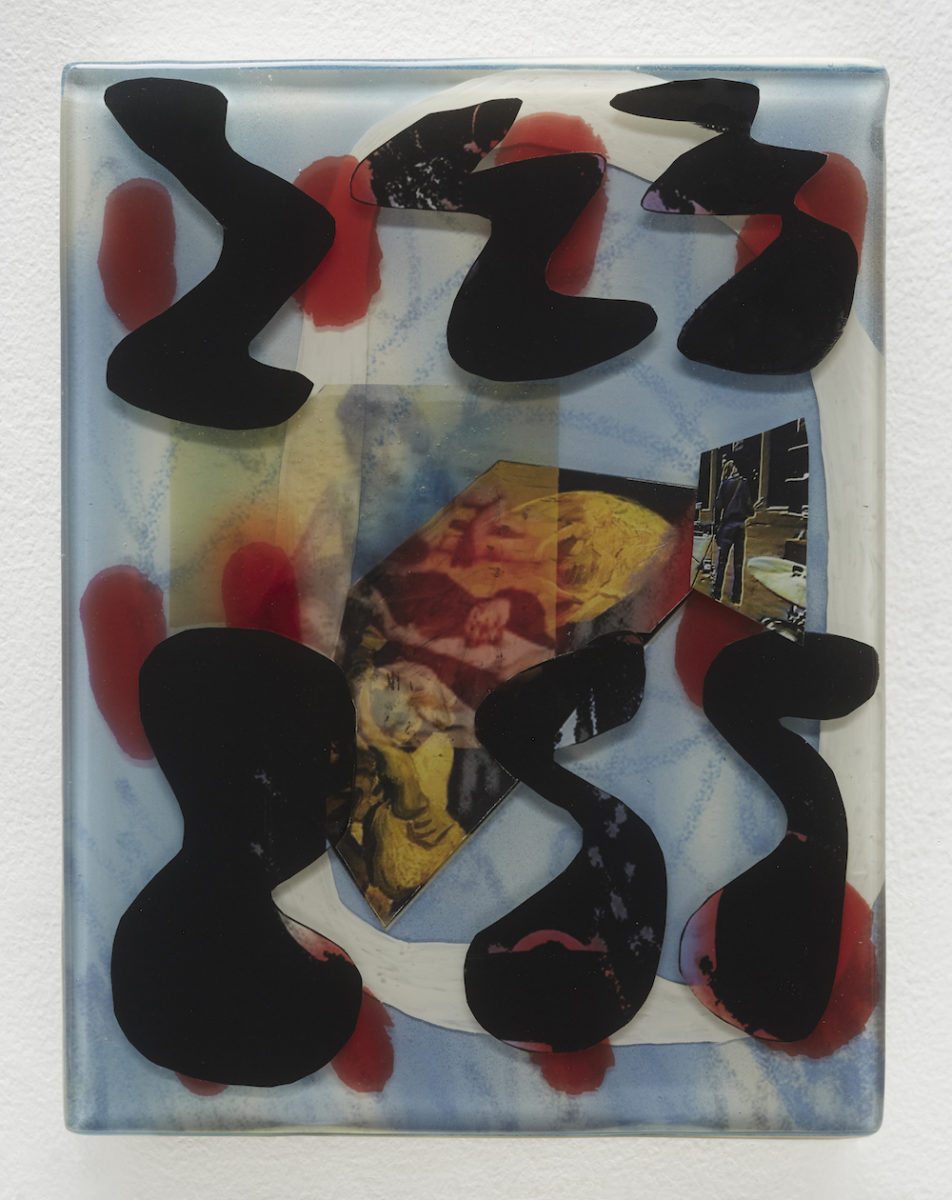

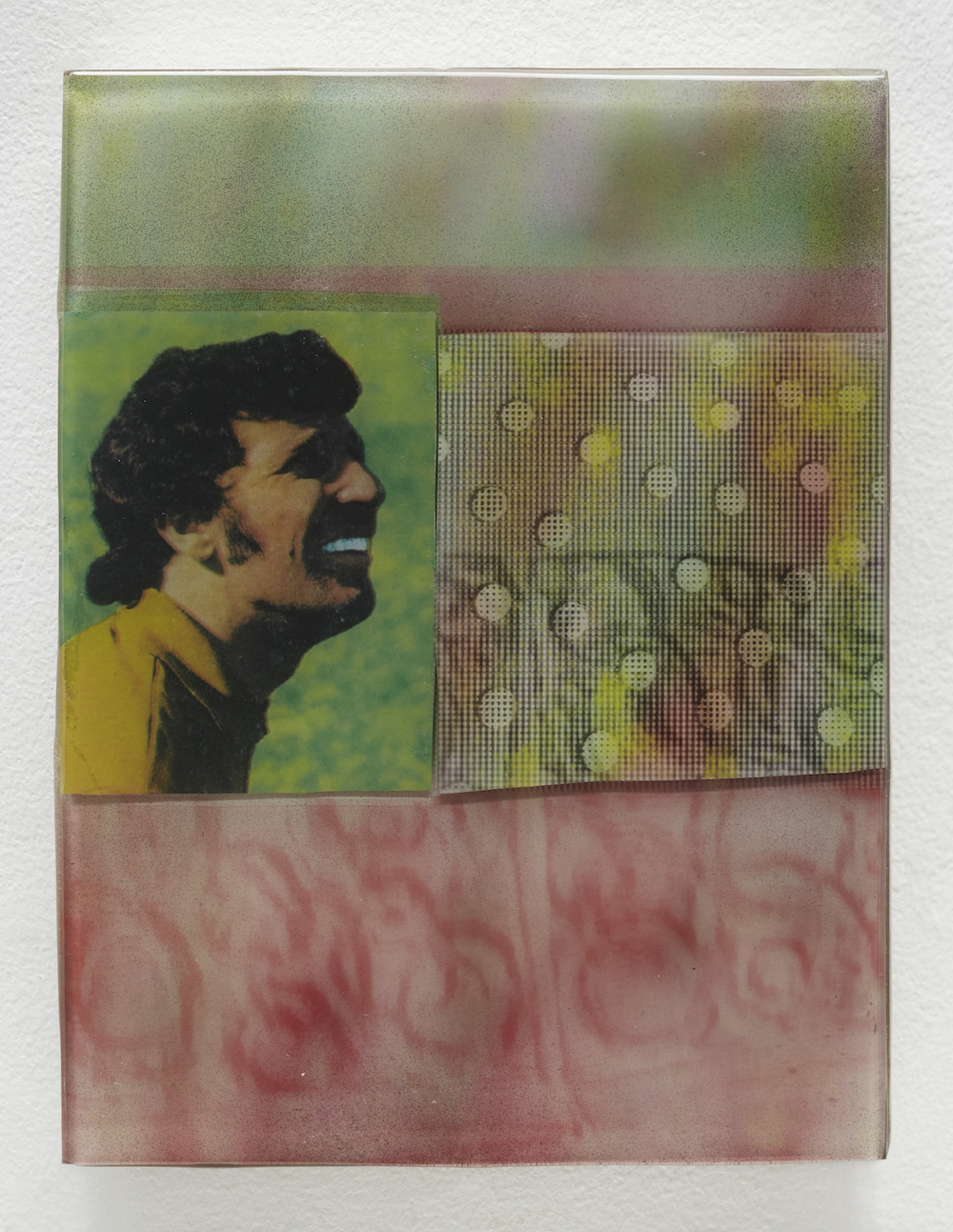

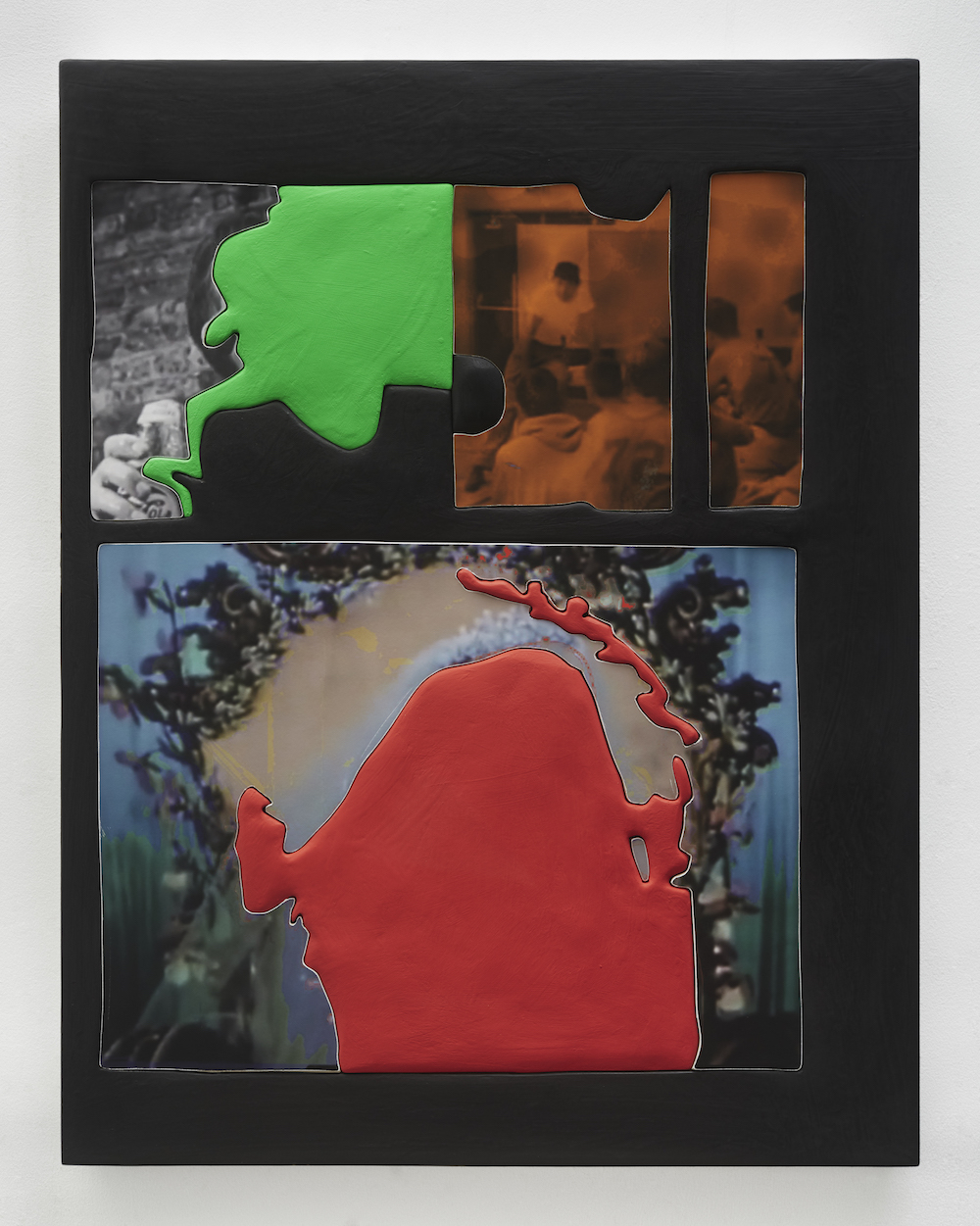

Sleep Rock consists of eighteen wall-based assemblages (all works from 2018) spread over two rooms. The majority of the works on show are smaller than a sheet of A4 paper, and are made using a technique new to Benning: semi-translucent compositions created from layers of clear resin, paint, cut up photographs and newspaper clippings. (If there was a cathedral for collage worship, these could be the stained-glass windows.) Gender remains a central theme, but the precocity of youth has abated. In its place is quiet contemplation and introspection. As the critic Roberta Smith wrote of Benning in 2009, this is the work of “an artist who has become sadder and wiser about life”.

- Out of the Bag

- Rebel

Benning’s latest works have a sibylline quality to them, a suggestion that they contain hidden messages for patient viewers. Take the black, grey and purple work Van, for example, in which a swirling candy-cane shape, sitting somewhere between classic barbershop signage and the form of a tornado, splits the composition in two. A gender storm, perhaps? Set into the resin is a picture of an old-fashioned beauty parlour—a garden-variety manifestation of gendered commerce and sociability—and a vending machine—another example of choice within a limited field. In the middle of the work is a photograph of a removal van. As I dodge my reflection in the work’s lustrous surface, I wonder if the vehicle is symbolic of transitioning, of Benning’s experience moving between and beyond the gender binary.

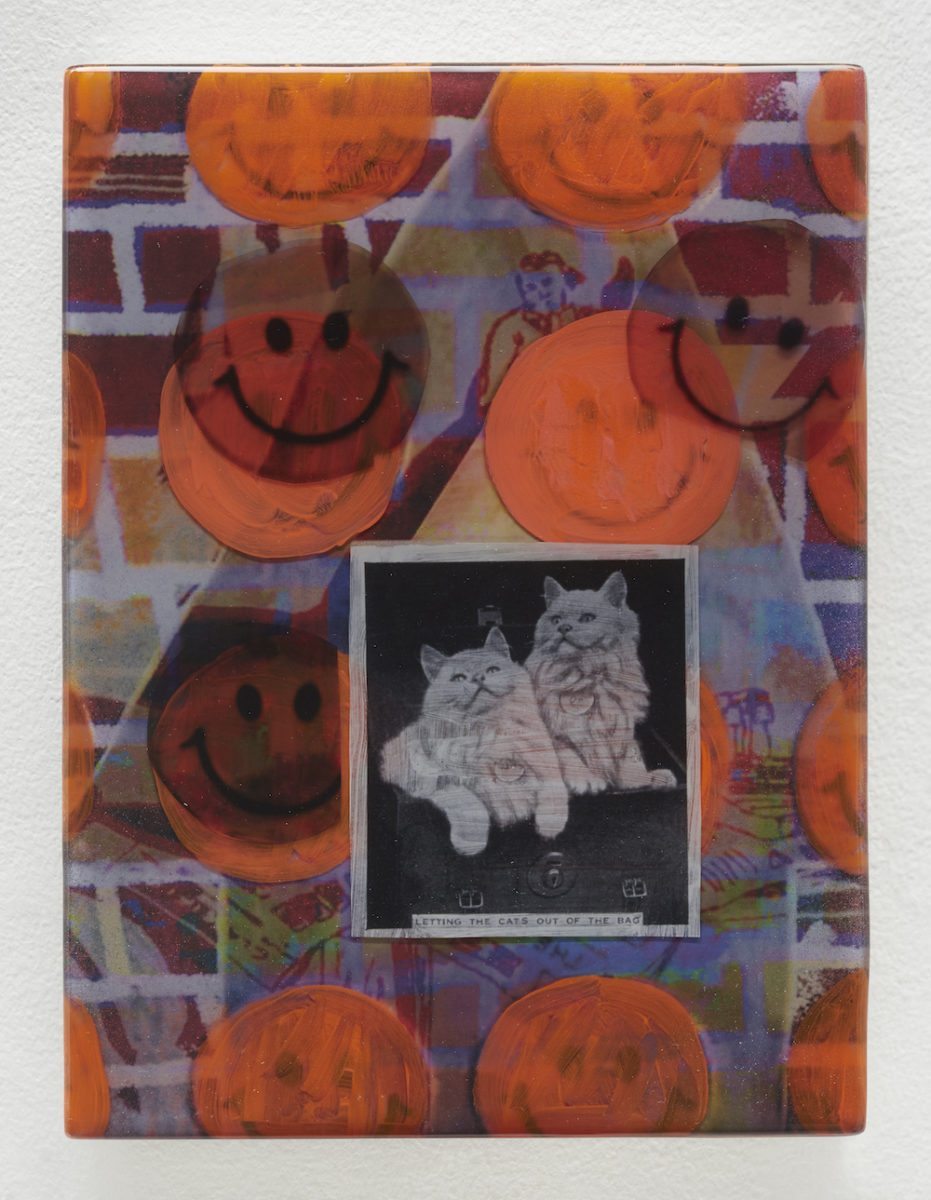

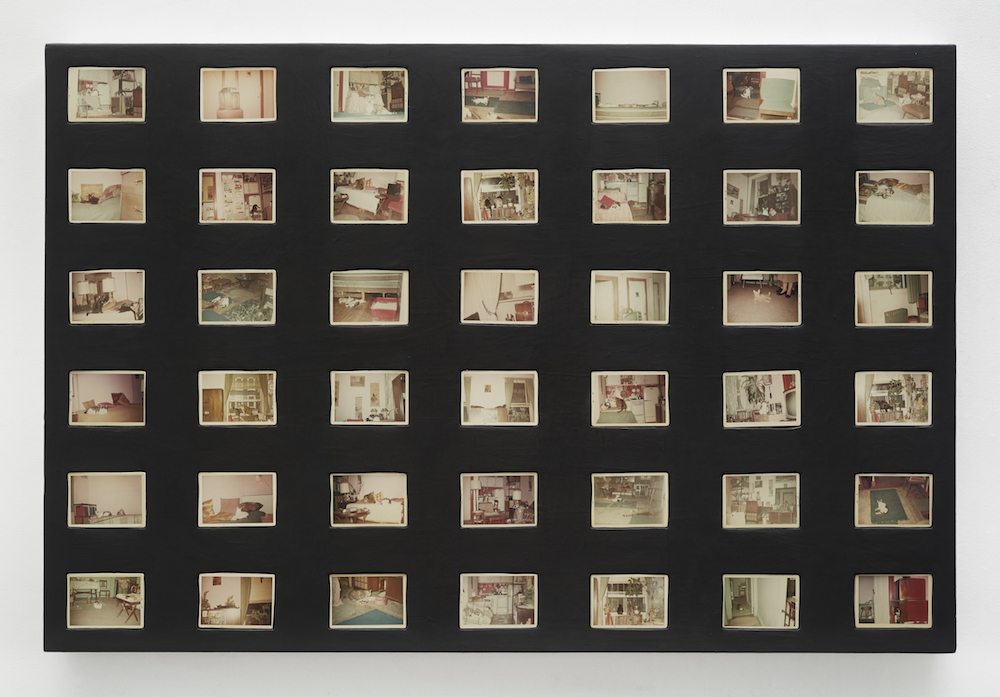

A surprising feature of Sleep Rock: it contains more pictures of cats than I can recall ever seeing in a gallery. In Cats—one of a number of larger works on show—a black panel is inlaid with forty-two found colour photographs of cluttered domestic interiors, each populated by moggies. The date stamps on the border of the photographs show that they were taken in the late 1960s. In Out of the Bag, layers of neon orange smiley faces float in the resin with manic intensity. A newspaper clipping in the foreground shows two long-haired, luxurious rag-doll cats, sitting on a suitcase. “Letting the cats out of the bag,” reads the caption beneath. As aliens in the home, cats are witnesses to and captives of domestic normalcy. Benning’s felines operate as a metaphor for revelations, states of foreignness and histories of confinement.

Parking Lot

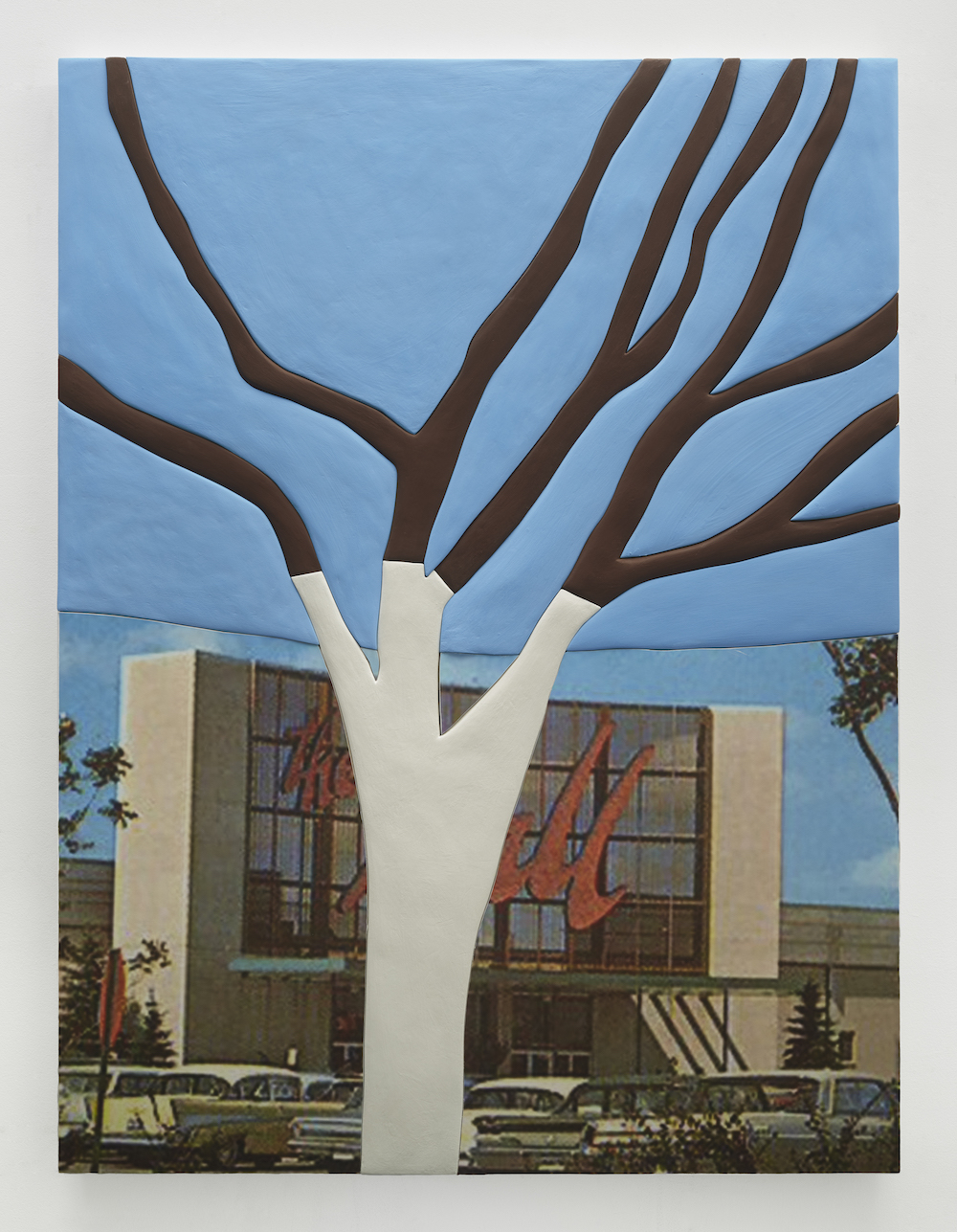

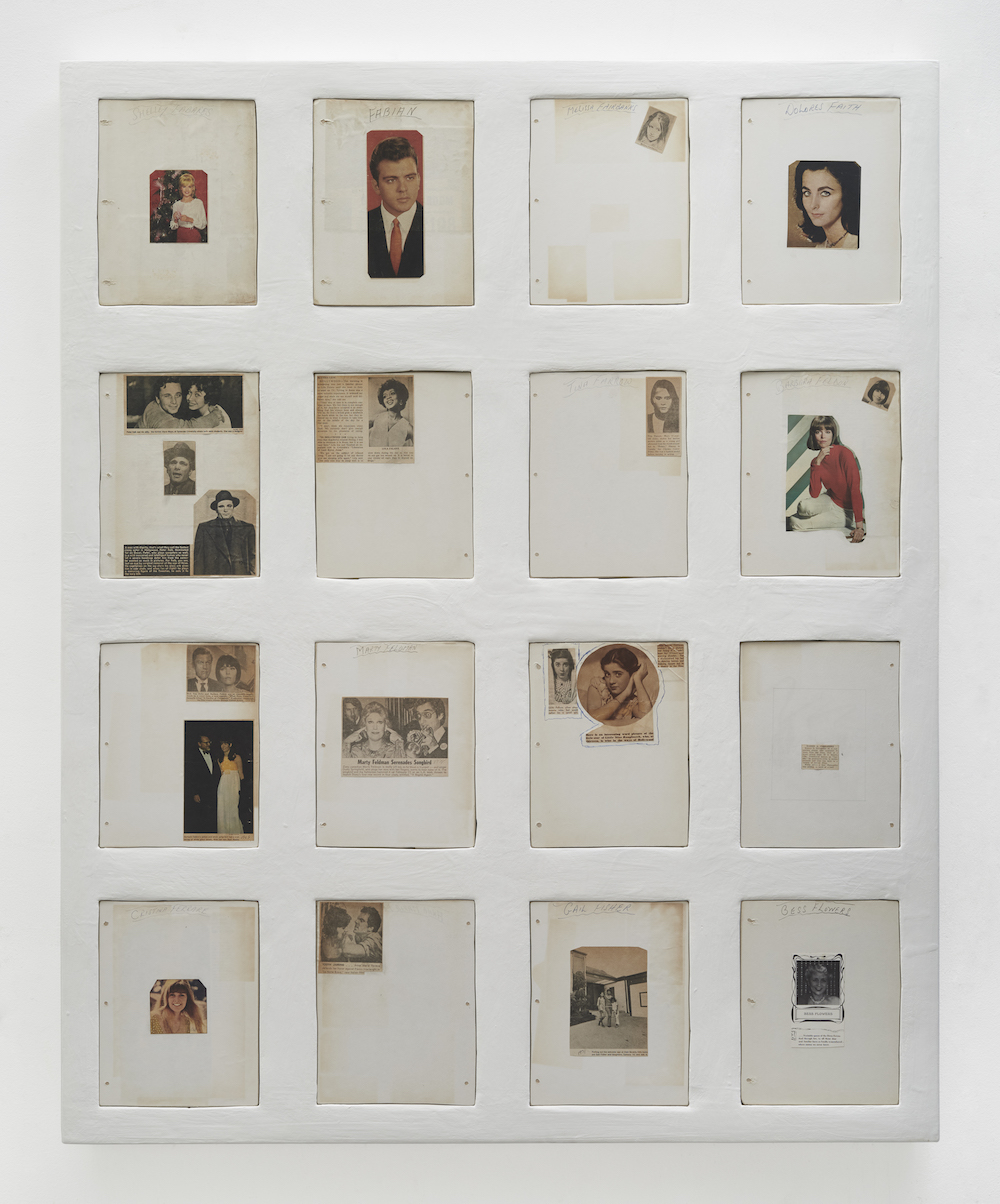

On the wall beside Cats is “F”, a white wooden frame inlaid with sixteen panels, each displaying newspaper clippings of Hollywood actors like the pages of a scrapbook. Among them is the child star Dolores Faith posing sweetly for the camera in the 1930s, and an obituary for a man named Ramon S Fernandez, nicknamed Tarzan for his performances in jungle scenes. Throughout the exhibition, images of midcentury America abound. There are the tail-finned cars in Tree Mall, and a Fonz lookalike in Mollegiato, set against a puckered peach and lime green background which reminds me of blistered skin. And there is the smiling woman in Pills, a composition that also contains a photograph of pharmaceutical medication. This latter juxtaposition calls to mind “Mother’s little helpers”—the colloquial name for benzodiazepines, the group of tranquillizing drugs prescribed to myriad women confined by domestic situations in the 1900s. At first glance I am resistant to the retro charm of this abundant Americana, but I soon realize its purpose is not to incite nostalgia. These images are the historic deposits of an oppressive gender regime: in the era of “Make America Great Again”, they serve as a reminder that the past is not always a place to idealize.

In her book The Lonely City (2016), Olivia Laing writes that collage enables its maker “to reconstruct the world”. By using materials close at hand, an artist can punk the visual hegemony, performing instant surgery on the status quo. Such was the case when the playwright Joe Orton and his lover (and later killer) Kenneth Halliwell defaced books stolen from a London library—adding, among other things, pictures of semi-naked wrestlers to their covers—crimes for which they served six months in prison in 1962. The works in Sleep Rock, however, aren’t interested in acts of semiotic revenge. Instead they touch upon collage’s suitability for capturing the complex and sensitive nature of identity itself: something that builds through accreted layers of experience and exposure; something we attempt to shape into legible and desirable form; something we edit, and which edits us back.

If once Benning sounded the klaxon on the battleground of youth, today the artist observes the shadows and listens to the echoes that follow us through adulthood. In the exhibition’s titular work, an amorphous grey shape hangs in the resin like a heavy cloud, against a backdrop of pink and black stripes. Set into the foreground is a photograph of a woman sleeping, her hair in rollers, a television screen on her bedside table. I leave the exhibition ruminating over the meaning of this image and its title. Perhaps “sleep rocks” are the archetypes and messages—conveyed to us by billboards and screens and the pages of newspapers and magazines—that lodge in the subconscious and haunt our dreams. Those things too big, and sometimes too painful, to simply pass on through.

All images courtesy the artist and Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects. Photography by Chris Austin