By the 1960s, the American artist, Philip Pearlstein, had abandoned abstraction as he “didn’t want to express other artist’s ideas any longer” but rather “paint what was in front of me”. Now ninety-three, his long career started in the 1950s when he studied painting at the Carnegie Institute of Technology. It was there that he met the high guru of kitsch, Andy Warhol, with whom he moved to New York to seek work in commercial design and peruse his own fine art practice. All through the 1950s he worked as an abstract expressionist before, rather unfashionably, shifting to realism.

Since the Sixties he has been pre-occupied with the human nude. “It is”, he says, “a shape that is always changing”. He admits to turning against the primary stylistic currents of his peers. Not least, because he wanted to make the teaching of figure drawing interesting to himself, as well as his freshman students when, at the age of thirty-eight, he began to teach at Pratt Institute. Although he continues to see himself, in many ways, as an abstract painter.

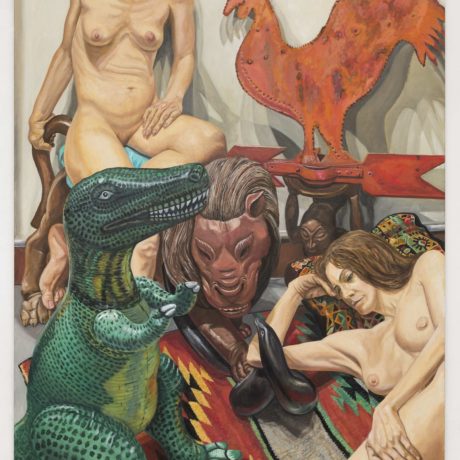

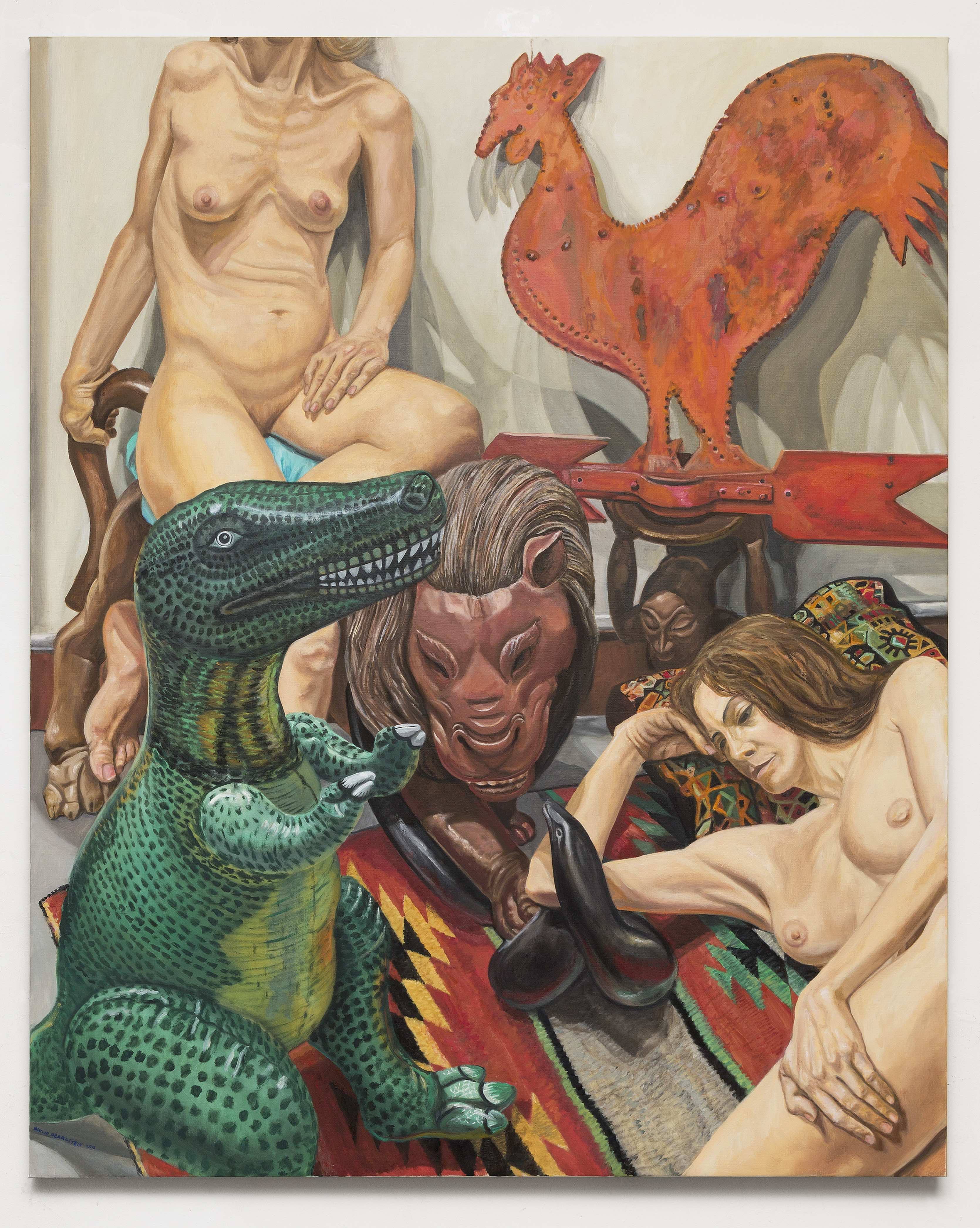

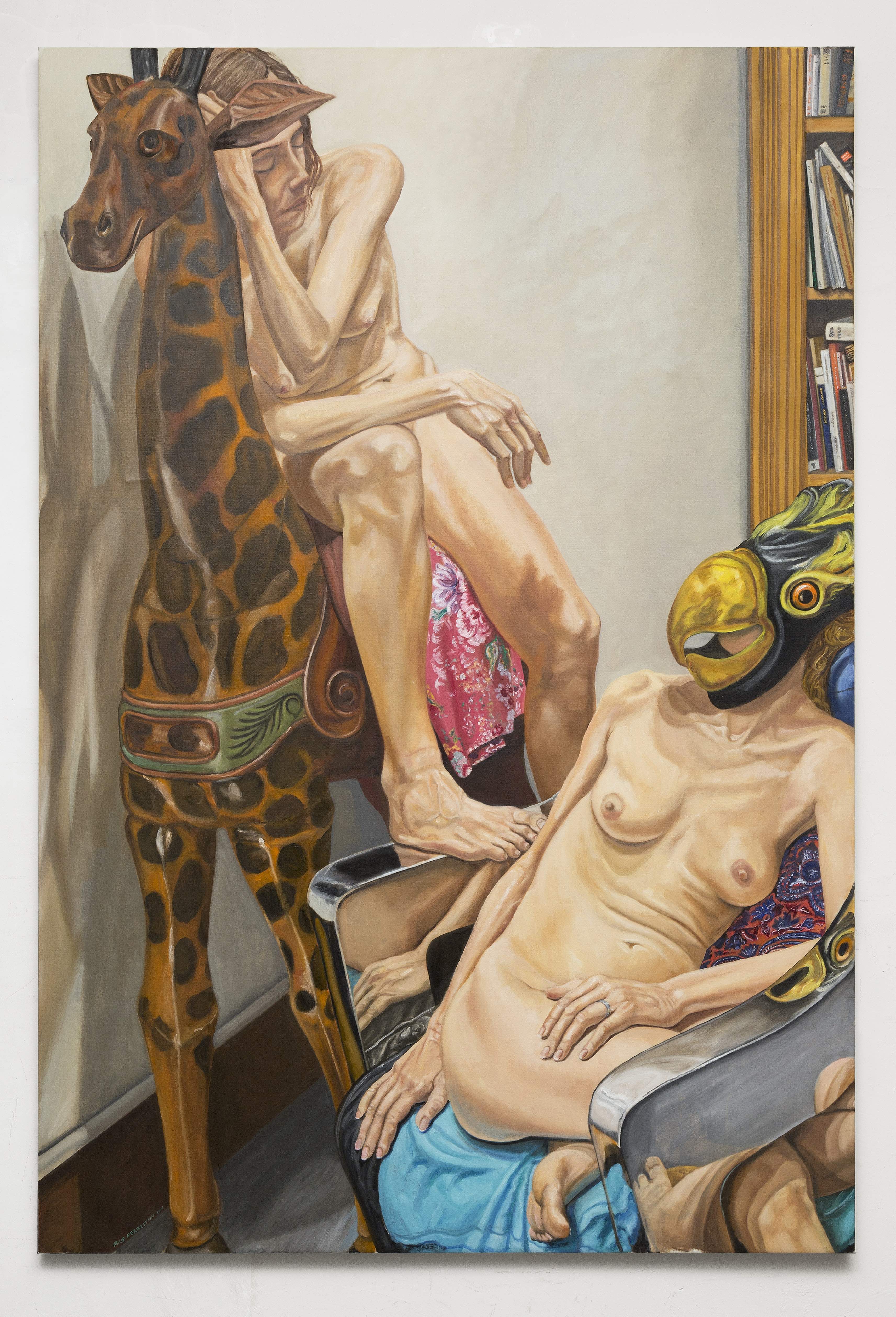

In the Eighties, he began to surround his sitters with objects from his personal collection, from cartoon blow-ups to African carvings. The result is a series of challenging compositions with complex view points and vertiginous depths of field that are both disorientating and disturbing. For, despite the amounts of bare flesh, there’s something inert about his figures that convey a sense of ennui and detachment.

“You can’t believe that these bodies have sexual relationships or exude sweaty secretions.”

Superficially you might think of the work of Lucian Freud, but Pearlstein is not actually interested in flesh. His flesh does not invite you to touch it, to sink into its depths or folds. It is not seductive. The limbs of his sitters are angular, hard and cold. You can’t believe that these bodies have sexual relationships or exude sweaty secretions. Their breasts, torsos, legs and arms are solid and inert, no different in texture to the wooden chairs, the African carvings or plastic toys that proliferate these canvases. Painted with sculptural flatness, his figures have no more value than the giant wooden giraffe upon which one of them rides, the inflatable green alligator or the rusty-red cockerel weather vein. The flatness of his paint gives everything the same weight and worth.

And none of his models meets the viewers’ gaze. Many have their eyes closed as if suffering from narcolepsy. They seem oblivious to the world around them, shut in their own introverted reveries. Even when there are two figures held within a picture space, their relationship is simply spatial rather than relational. A woman lies among a clutch of surreally large wooden decoy ducks. Her hand rests on one of their backs. Elsewhere another clasps a wooden swan, her eyes closed in what might be post-organism bliss, in this latter-day version of Leda and the Swan.

“Not only is Modernism dead but Postmodernism isn’t too healthy either.”

In this world, where all quietness is filled with busy patterns and crammed with objects, everything is given equal weight. There is no hierarchy, no implicit moral terrain here. Pearlstein is not interested in the existential lives of his models or in their inner landscapes. In Two Models, Polished Steel Chair and Swan Decoy (2016) his fascination is with the complex relationship of limbs that splay from a cold glass and steel chair, with how the feet and hands relate to the geometric patterns on the Anatolian rugs.

As a practicing graphic designer, he learned how “to respect the vertical and horizontal play of subdivisions within the rectangular picture plane in the manner of a Mondrian composition”. He also studied Matisse’s use of “positive cut-out shapes, playing against the background shapes they created”. But it was to Piero della Francesca, a hero from the days when he studied the Italian Renaissance, to whom he turned to develop a sense of three dimensionality. He was fascinated by the geometry of the ‘golden section’ rectangle used by Piero as the basis of all his painting compositions. Piero also published his own drawings on how to apply the rule of two-point perspective in drawing human and architectural forms, as devised by his contemporary, Brunelleschi. Such studies led Pearlstein to realise that here was a great pictorial idea that had all but been abandoned by the 20th century. It was to give him a new painterly grammar, which he has likened to the linguistic invention of contemporary poets.

In Two Models with Giraffe and Bird Masks, Chrome Chair and Bookshelves (2016), a lounging nude is encased in a bird mask. This echoes the immobile faces of the African carvings that appear in other of his paintings. Pearlstein’s canvases exude stasis. It’s as though the air has been sucked out of these rooms and the figures are simply waiting in silent ante-chambers for death. There’s also a fascination with “primitivism”, flagged by the various ethnic carvings and the patterns of the rugs that echo Matisse’s exotic appropriations. These, though, are juxtaposed with the pneumatic figure of a Michelin Man, a model speed boat and the figure of a Tyrannosaurus rex standing on top of a plinth.

The message seems clear. Not only is Modernism dead but Postmodernism isn’t too healthy either. The high Modernism of, say, Edvard Munch’s The Scream––that canonical expression of isolation, individualism and angst–– is gone, but so, too, is the postmodern discourse that critiques such ideological, metaphysical and humanistic work. So, what is left? It seems that what Pearlstein is offering in this void is structure, careful practice and artifice. For this series of complex painted constructions that appear, superficially, to be about the human form and body, actually reject all the messy clutter, the complex subjectivity and raw disordered stuff that makes us human.

All images © Philip Pearlstein. Courtesy Betty Cuningham Gallery