Salón ACME, a highlight of Mexico City Art Week, has been considered by some to be more of a mini biennale than an art fair. Housed in Proyectos Público, a restored historic home in Colonia Juárez maintaining its charming elements, a diverse set of installations from artist seem perfectly in place of a traditional fair booths and white walls, it is truly an experience not to be missed. Created as an art platform by artists and for artists, it also gives visibility, promotion, and dissemination to emerging curators, which lends Salón ACME an extra layer of an in-the-know feeling that had the crowd buzzing with excitement and engaging in deep conversations. Since 2013, it has held ten editions, this year with six sections: Bodega, State, Projects, Patio, Sala, and Open Call, and has positioned itself as one of the most authentic contemporary art events internationally, fostering new audiences and consolidating a community of artists, curators, and collectors.

As noted by Ana Castella, the Director of Salón ACME, “This edition is particularly special, as the project enters its second decade and we are at a point of transformation and growth. My focus as director has focused on giving more space and clarity to each section, strengthening and expanding collaborations, as well as building stronger relationships with the venue where it’s held: Proyectos Públicos. I am thrilled to lead this project and contribute to the different possibilities of the artistic landscape from Mexico City”.

Derzu Campos’s work delves into an underground sci-fi dystopian world that feels like taking a peek into an ambitious scientist’s lab. His “living sculpture” incubating on display in an aquarium illuminated by a bright fluorescent light will become a fossil of our age as the days go on the materials meets their final degradation. The work was created with the accumulation of familiar found objects grouped together by the artist according to material, aesthetic, and conceptual characteristics are “stacked in apparent precariousness, ‘wrapped’ then ‘infected’ by bioplastics from diverse origins that function as a species membrane or interface between industrial objects and the external environment”. Campos is creating these experiments to answer critical questions and help form considerations for viewers on “What future does it hold for objects in a post-human world? What use will they have if no one remembers how to use them? Could they mutate? Evolve? Will they become specters – the residual trace of civilization?”

Nicola Arthen’s work is a nod to the Jacquard loom and history of computer programming. Invented by Joseph Marie Jacquard, the Jacquard loom sped up the process of weaving complex textiles by translating instructions into punched card sequences that gave the loom instructions for raising and lowering warp threads. This “language” of weaving was an early form of binary, the language of 1s and 0s that still drives computing today.Arthen’s automatic Jacquard loom represents a double image. One image (a machine-like sensory organ) was modeled in 3D software by the artist, and the other is a “reflection” of it, generated by AI, representing its unsettling evolution towards humanism. “The processes involved establish a conceptual connection between computer networks and the Jacquard loom as a machine that was the first to use the binary code system of modern computers, the same system that now houses Artificial Intelligence.” In this work, a woven loop represents a pixel.

Santiago Gómez’s mixed media sculptural work is a spiritual relic of consumer culture and mythology, featuring Monster energy drink cans, headphones, iridescent beetles, and more, acting as an investigation into the pervasive nature of capitalism, branding and “the constitutive materiality of the objects that fuel its consumption.” Focusing on understanding and producing fictional complexes, Gómez uses the Monster cans as an anchor, tied to the themes of terror “capitalist” and a humidifier filled with the contents to visualize “material strategy of disintegration and mixing of materials, as well as the myth of Tezcatlipoca as a reference point to think about the cultural and material limits of the smoky reflection of Capital.”

Jonathan Vázquez’s emerald green reproduction of a pre-Columbian sculpture resting in a generic big-box store shopping cart is a humorous criticism of the fetishization of pre-Hispanic objects in the present, the auction market, and international museum collections. His work began as an “exploration of coloniality and its aftermath, such as censorship, political violence, disappearance, cultural extraction, and its aesthetic products.” This work is part of a project that explores the concept of cultural extractivism through fiction, consisting of a supermarket that offers sculptures from the National Museum of Anthropology of Mexico as a consumer product. The sculpture in this particular work corresponds to a replica of a Cocijo vessel found in tomb 104 at Monte Albán of the Zapotec culture, to which Vázquez belongs.

Alejandro “Luperca” Morales’s intimateself-portrait moving through a seemingly industrial space wearing a hoodie from the famous Texas burger chain Whataburger is quite unassuming till learning it’s an archive image from the camera in front of the Paso del Norte International Bridge on the border between Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, and El Paso, Texas, a notable volatile space on the conversation on immigration. A recent project from Morales, this portrait is one of a series documenting his border crossings while carrying and wearing objects that fuel the discussion about what happens in this space. Seeking to “question the official narratives presented to us and the way we interact with migration as global beings.” Critically analyzing the migration policies of the US and Mexico.

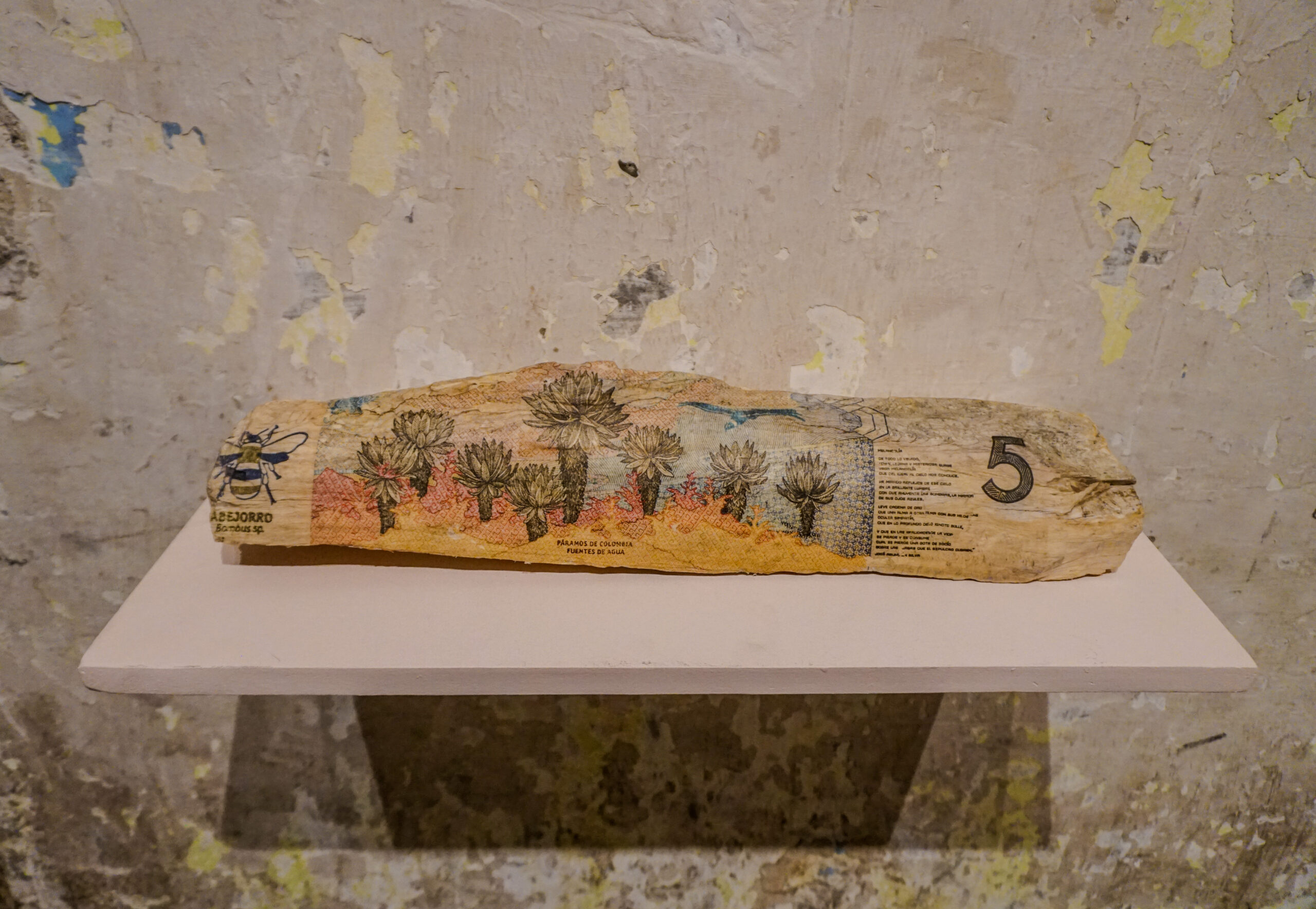

David Guarnizo’s organic stone sculpture with a colorful image transfer of the 10,000 Colombian pesos, this series using a banknote from 2016 was manipulated through digital editing, so only the natural landscape remained. In this work, Guarnizo is exploring “the quantification and commercial valorization operation that the banknotes seem to play on the landscape by overlaying figures, seals, and signatures on representations of the territory.” Similarly seen in currencies across the world, banknotes often highlight plant and animal species that are being threatened by the continuous actions of environmental degradation, such as the logging, oil, and mining industries so prevalent in the region. While forming his work, Guarnizoinvestigates many factors while creating the boundaries in his work, exploring notions of landscape and territory. As he constructs an image of the landscape, he visualizes the lines that delineate a photographic frame similarly to the borders that define a territory and investigates how different communities around the world construct how their values and identity are connected to their land and “materialize in exchange objects, such as certain intervened stones or metals, or more recent numismatic elaborations like banknotes, coins, or even digital currency.”

Adeline de Monseignat’s relief style travertine and bronze sculptures embedded into the distressed walls of Proyectos Públicos spontaneously form part of her ‘Slab Works’ series, which started after becoming a first-time mom, led her to “decided not to worry so much about creating “perfect” drawings” but focus on continuously creating. The forms that emerged from these sketches became an abstract representation of “memories of pregnancy and moments of embracing her son’s small body against hers.” As presented in this work, Monseignat’s use of circular and intuitive forms and organic material appears as a way “to materialize the spiral of existence, vulnerability, sensuality, and presence. In contrast, materials like bronze and steel suggest a symbolic language of strength, resilience, and transformation”.

Andrea Nones-Kobiakov’s delicate dusting of white ceramic and sugar pieces, ever-evolving in their position on the thin wires suspended in the corner, is representative of the passage of time and memory. “Suspended in limbo, moving slowly, floating through empty spaces, stumbling among themselves and others. In this series, there are no exact copies because, like memories, they adapt and change according to the context, emphasizing levels of the fragility of memory associated with forms of processing trauma”. Additionally, Nones-Kobiakov’s education in pastry with training from Le Cordon Bleu informs her practice on what is crucial is that the process of creation and the role of food in “the dynamics of communication and as a driver of daily rituals.”

Antoine Granier’s symbolic goddess of futurism, blending multiple cultures and points of time as a representation of the metamorphosis of our societal changes from the roots of ancient trees to gleaming skyscrapers. Visual artist and filmmaker Grainer’s work creates fantastical narratives imagining characters and encounters aiming to circumvent different forms of control on the bodies of the inhabitants of large cities.

ARMORPLAST, the first collaboration between artist Ismael Urmeer and fashion designer Vanebon, is a cartoonish sculpture resembling a spaceship control center exploring a surreal neon landscape. A playful integration of both of their styles and inspiration of toys, pop culture, experimental physics, anime, and “20th-century technological acceleration to craft a hybrid of machine-landscape-body.” Through this collaborative work, they desired to “provide a biotechnogeometric figuration and abstraction that revisits the concept of a world dedicated to progress and, consequently, industrial development.”

Written by Amber Smith