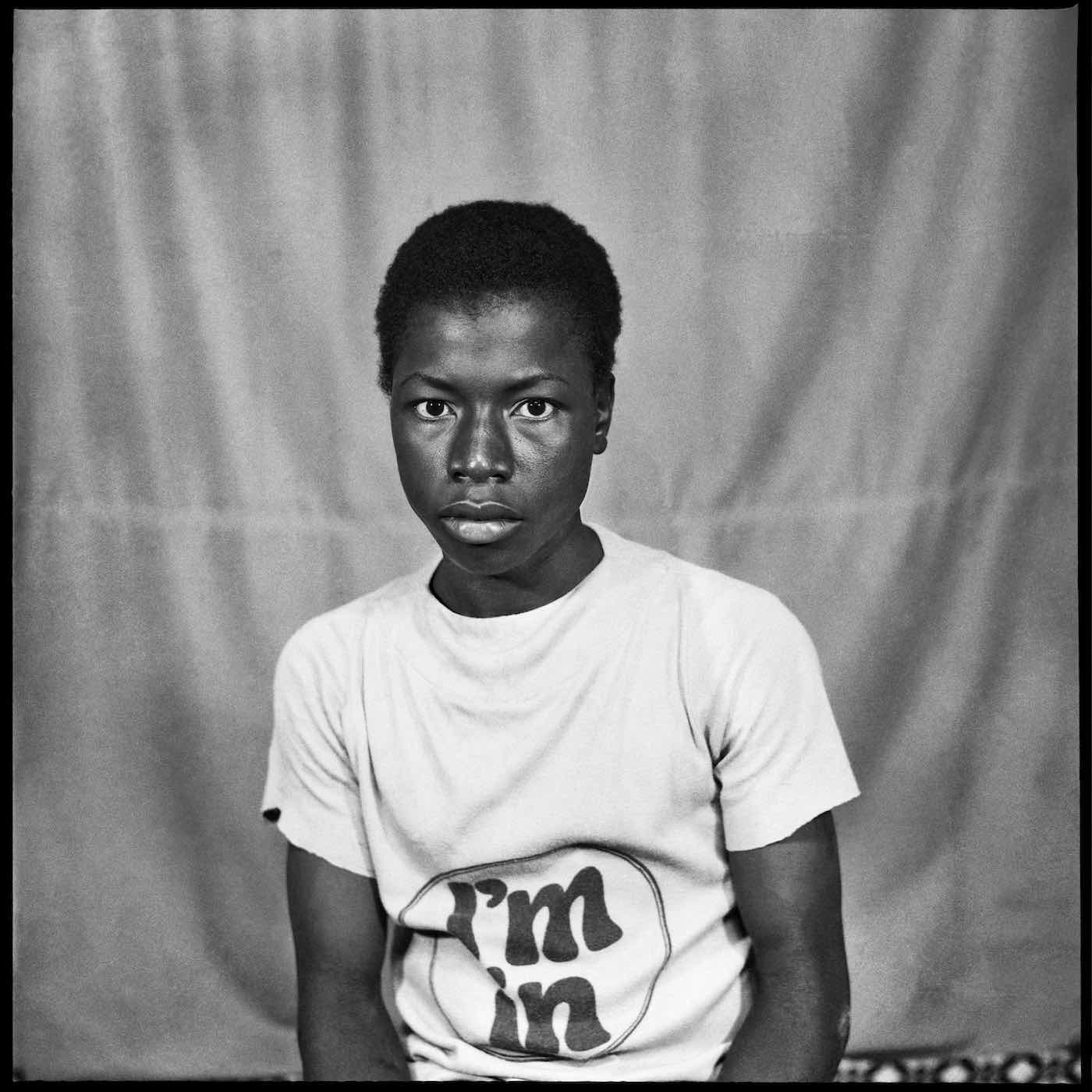

Gelatin Silver Print © Sanlé Sory, Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

“I don’t normally believe that a button or tote can be the catalyst of change that we need to see in our world today—consuming product doesn’t often lead to social justice, ya know?—but the stakes are far too high these days,” Marjon Carlos, a senior fashion writer at Vogue said last year, observing the 2017 trend for t-shirts brandishing political statements, oozing over the appearance of Black Lives Matter slogans on the catwalk. At the same time, Americans wore plain white tees for Obama.

The stakes for some have always been high—and t-shirts have always been there to gird our bodies. If the camera is the democratic medium, then the tee is the democratic garment, universal, unisex and ubiquitous. In the 1980s in the city of Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso (then known as The Republic of Upper Volta), t-shirts were as much the garment of choice for the youth as they were anywhere, and at Sanlé Sory’s

Volta Studios, one of the first photographic studio in Bobo, the artist was there to document them on 6×6 film (the favoured format of the day).

In the same year, 1980, the Republic was emerging from a devastating period of drought, famine and labour strikes. In November that year, President Sangoulé Lamizana was deposed by Colonel Saye Zerbo, himself overthrown just two years later. In 1983, a third coup d’état in as many years eventually saw the revolutionary Pan-Africanist Thomas Sankara become president. It was Sankara who renamed the nation, and who is credited with making radical changes: banning female genital mutilation and forced marriages, appointing women to his government, and introducing mass vaccination programmes and a national literacy campaign.

Yet Sory’s t-shirts only hint at those scenes blistering in the background. Taken in the early 1980s (and curated as a series later) the politics are only there if you look for them: the title of a portrait of a young man in a funky “I’m In” tee, Je Suis Dans Le Coup, (a play on the French Je Suis Sur Le Coup, ‘I’m on it’ alluding to Sankara’s coup); other designs are of global Black icons: Cassius Clay, Bob Marley and Sankara himself, many of them perhaps manufactured and distributed during the Black Power movement, and worn with pride by their anonymous owners. Other t-shirts have a more romantic tone: “Serre Moi Fort” (Hold Me Tight), implores one; “Reviens a Moi ChouChou” (Come Back to Me My Love) urges another. The t-shirts are a record of eighties graphic design and sentiment, as much of politics and culture; they’re what connects these young men in Bobo to young people everywhere. Their t-shirts remind you of your own fusty favourite, infused with the scent of something that mattered.

Unlike many of his other portraits, shot against backgrounds painted by commissioned artists from neighbouring Ghana and Benin, the t-shirt portraits are minimal, the fabric stretched tight, the young men’s faces sombre, wistful—distinct to the atmosphere of fun and self-staging Sory encouraged in his clients who would dress up and fantasize in front of the camera.

A t-shirt, as Carlos said, probably isn’t going to change anything. Now aged seventy-five, Sory contributed to the second generation of studio photographers in West Africa whose work empowered post-independence identities. Taken when photographs were still analogue, now they are perhaps even more significant as a legacy of rarefied memory; one of few visual narratives at a turning point in Burkina Faso’s history, told from the chests of the young generation.