Santiago Sierra

Adopting social architecture as a mode of critique is a technique that has become synonymous with Santiago Sierra’s artistic practice. If the results are often painful, the frequent criticism made of his work that it perpetuates the brutality of an already merciless society is misleading. In 2006, Sierra stated his work is produced not as an image of society, but as society itself: “the only thing that the work does is tell [the audience] in which direction I want them to look.”

On 13 and 14 April 2015, Sierra completed Part 1 of Black Flag, planting the universal symbol of the anarchist movement, the black flag, at the geographical North Pole, latitude 90º N. On 14 December 2015, exactly 104 years after Roald Amundsen’s Norwegian expedition, Part 2 of Black Flag was completed when a second black flag was planted at the geographic South Pole, latitude 90º S.

- Black Flag, North Pole, 14 April 2015

- Black Flag, South Pole, 14 December 2015

Answering the question “Why is our flag black?”, the sociologist and anarchist Howard Ehrlich explained: “Black is negation, is anger, is outrage, is mourning, is beauty, is hope, is the fostering and sheltering of new forms of human life and relationship on and with this earth. The black flag means all these things. We are proud to carry it, sorry we have to, and look forward to the day when such a symbol will no longer be necessary.” This sentiment captures the binary antagonisms that function as guiding paradigms of several aspects of Sierra’s work: in his subject matter, method and in the monochrome of black and white.

Bracketing the entire globe between the two poles, Black Flag positions itself in the ambivalent grey area of the in-between. It stands as an a-national claim to the spaces of an a-territory, a claim made in the name of all people, above and beyond states and borders. Black Flag conflates and rejects both histories and ideologies in one minimal stroke. With an established reputation as a “divisive” artist, in Black Flag Santiago Sierra presents a clear disjuncture from the past, a utopian grand gesture—sympathetic and absolute.

“I wanted to create an anarchist icon that was a source of pride and courage”

Rather than being invited to respond to a particular context, here you were given carte blanche to create an artwork you may previously have thought impossible. When did you initially conceive of this work and how was the idea formed?

In the last few years I have put up black posters in different European cities: Berlin, London, Madrid, Basel, Istanbul, Viterbo. Someone connected it with Malevich’s Black Square and the series was included in an exhibition dedicated to the continuity of his legacy at the Beyeler Foundation in Basel. The most radical black square on white background, however, is an anarchist flag on an extremely snowy landscape. I also had in mind Piero Manzoni and his pedestal for the world (Socle du monde, 1961). This was a work that appropriated the whole world and made us think of the earth as one whole thing. Of course I wanted to create an anarchist icon that was a source of pride and courage, that made you think that the planet is ours when you saw it. I have created many works of a hurtful ugliness. However, I see Black Flag as the most poetic of my works, without doubt the most beautiful of the ones I’ve done until now.

The idea of beauty is intriguing as it marks a departure: your work is often seen to be coarse and “without enthusiasm”, to use Gustav Metzger’s term. Here, in the aesthetics and in the scale, there is a sense of the sublime. Do you feel that you have become more hopeful than in your younger years?

Hope, like fear, paralyses, and I don’t like either of them at all. In Spanish “hope” is esperanza, which implies waiting for something. I see very few reasons to sit and wait, even less so with age. Hope evolves in the opposite way to what you describe: the older you get, the less there is left. And that helps when facing the artworks. What has indeed eased off is the intensity of my rage, or at least the way of channelling it. Somehow I have gotten used to it.

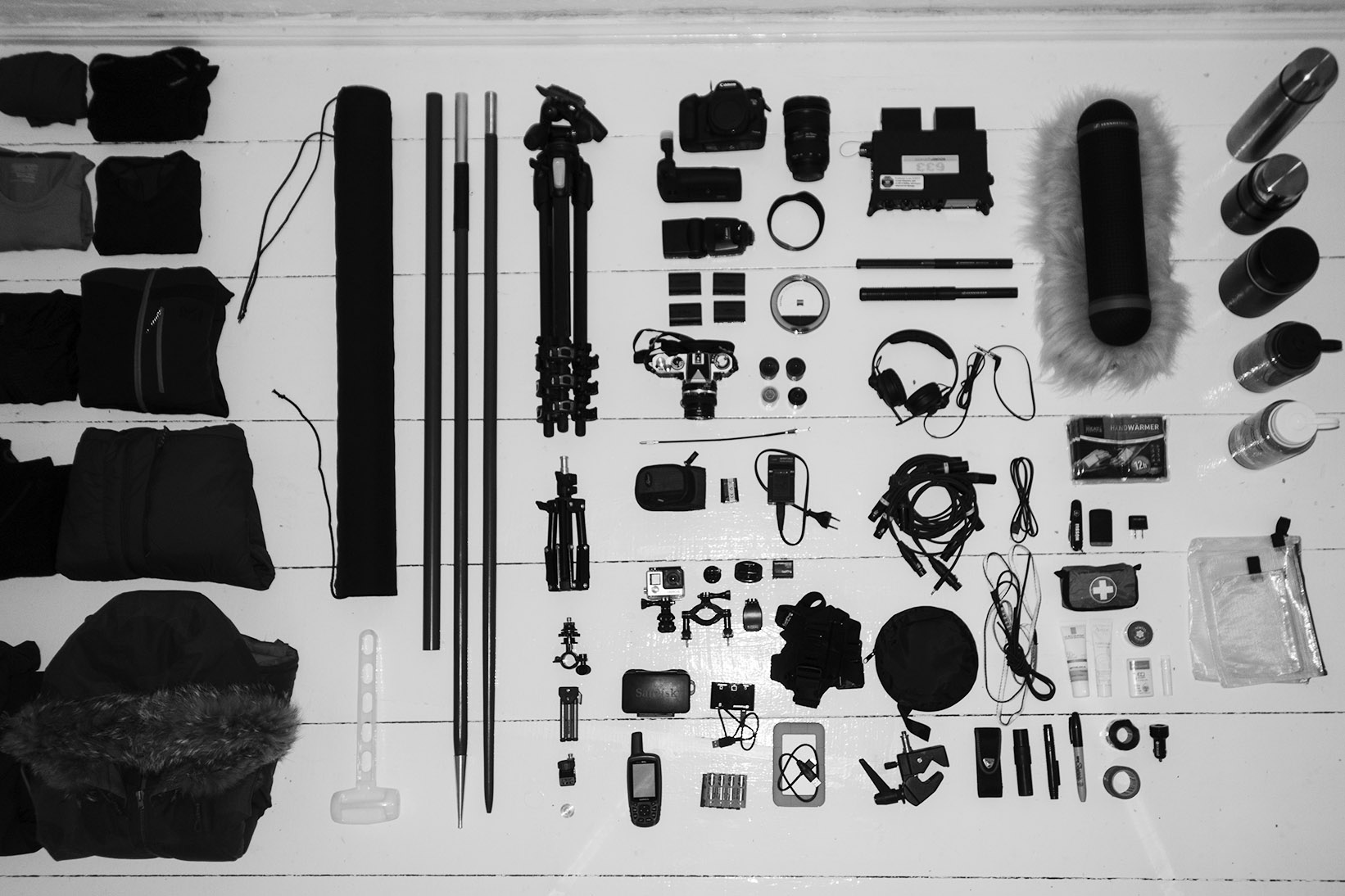

Your gestures are documented by way of video and photography. For Black Flag, photographs are presented alongside the master records pressed with the sound at the geographic North and South Poles. There is also the flag, which we should stress is not the one in the photographs—these were left in situ. Can you say something about the objects that were produced to represent the project?

It is a way of telling the story. There are other ways that I have discarded, such as video or any figurative or theatrical approach. I like the document and the “relic” that result from a performance. They are the tangible remainders that speak of something that happened in a place and time different from ours. In my work the facts are very important, what happened, as something documented and subject to verification. The idea of the sound recording was particularly attractive because it invites you to listen. The replica of the flag gives a lot of solemnity to the act.

We should think more about the sound element of the project, the recording of what you describe as “white noise” and how it acts as volume. Your work crosses between installation, performance and photography; however, to me, the overall impression is one of sculpture. This can be seen without doubt in Protected Building, at Manifesta 11, where you asked us to engage with the actual, physical space and its vulnerabilities.

In your question you describe it perfectly: white noise is a noise with volume that takes up space and gives it texture and life. I really like the sound works by Francisco López precisely because of that sculptural dimension he gives to a sound, which can almost be touched. He also interests me for the imposing character of his perception. We can close our eyes but not our ears, which is why we feel invaded by the perception of a sound.

If we refer again to the flag as an object, it represents a nation state; its purpose, socially, is to connect individuals under a shared identity, incentivizing patriotism and hope. Politically, the flag is a symbol of power, influence and domination. You used the Spanish flag in your work Black Flag of the Spanish Republic (2007); in Black Flag (2015) you chose the symbol of anarchism. What does the status of the flag mean to you, in a world that bears constant witness to the individuals who die for it?

With Black Flag of the Spanish Republic I was looking for an association between the Spain of the Black Legend and the reality of the blackened Spain. I also used the US flag, in 2002. I placed a US flag of 20 x 15 meters at the Museo la Tertulia in Cali, Colombia. I knew they would try to burn it, but we had to be attentive to put the fire out in time. One night they burnt it partially. I took the flag with me and exhibited it at MoMA PS1 in New York. In addition to this, there are several sound works using national anthems, which are the sound versions of flags. Flags, national anthems and all of that garbage comply with a despicable ideology that defines people in the same way that a red-hot branding iron defines livestock. The black flag is the flag of all of us who don’t identify with a flag or don’t want to have a flag, something to visually set against the multiple colours of the patriotic cloths.

The nature of nation-state claims to the polar regions is, in part, performative—take Russia’s 2007 stunt, for example, when they sent a capsule to drop a titanium Russian flag underwater on the Arctic seabed. This controversial symbolic gesture was a motivating scene of intent, causing us to consider whether politics and art are closer than we think. Could Black Flag

also be perceived as propaganda?

Art is a language that appeals more to sensibility than to rationality. That’s why Plato threw us out of his Republic. This makes us always look a bit like demagogues and yes, close to propaganda. What would there be of the Pope without St Peter’s Cathedral, or armies without their emblems and their marches, or of politicians without their fictional plots, their chants and colours? Probably nothing. Art is sometimes the Pied Piper of Hamelin. It all depends on whom the flautist works for.

“It was the flag of freedom, but it was also a flag of mourning for the anarchists fallen in the battlefield”

Issues of territory are at the forefront of contemporary political debate: Brexit, the refugee crisis, the rhetoric of the US presidential campaign, all reaffirm our split society through imagery of walls and borders. In works such as Space Closed by Corrugated Metal, presented at Lisson Gallery’s inaugural exhibition in 2002, and Wall Enclosing a Space at the 2003 Venice Biennale, you construct material borders that, you have commented, act as a symbol of both repression and emancipation. To what extent do you see the gesture of claiming the polar territories within this binary context?

The black flag was a binary symbol from its first appearance in the Paris Commune. It was the flag of freedom, but it was also a flag of mourning for the anarchists fallen in the battlefield. Here we push this to the extreme because it is a clear internationalist gesture. Walls are the architectonic totem of our time, they are the most powerful sign of exclusion and division of the world as human cattle. But barricades also exist and are an adored totem of our time as well. Their message is “not a step back, you will not continue from here” (ni un paso atrás, de aquí ustedes no pasan).

How closely do your political views align with anarchism?

The anarchists are right.

This article was originally published in Issue 31

BUY NOW