Over the past 18 months, photographers have had to reckon with drastic changes to their working lives. Normally occupied with commissions and collaborative projects, the absence of their usual rhythms, source material and modes of working has led some to place themselves at the heart of intimate personal series as they navigate this newfound solitude. It has been an exercise in self-reflection, and an unsolicited yet valuable opportunity to unpick what it means to be an individual and image-maker in precarious times.

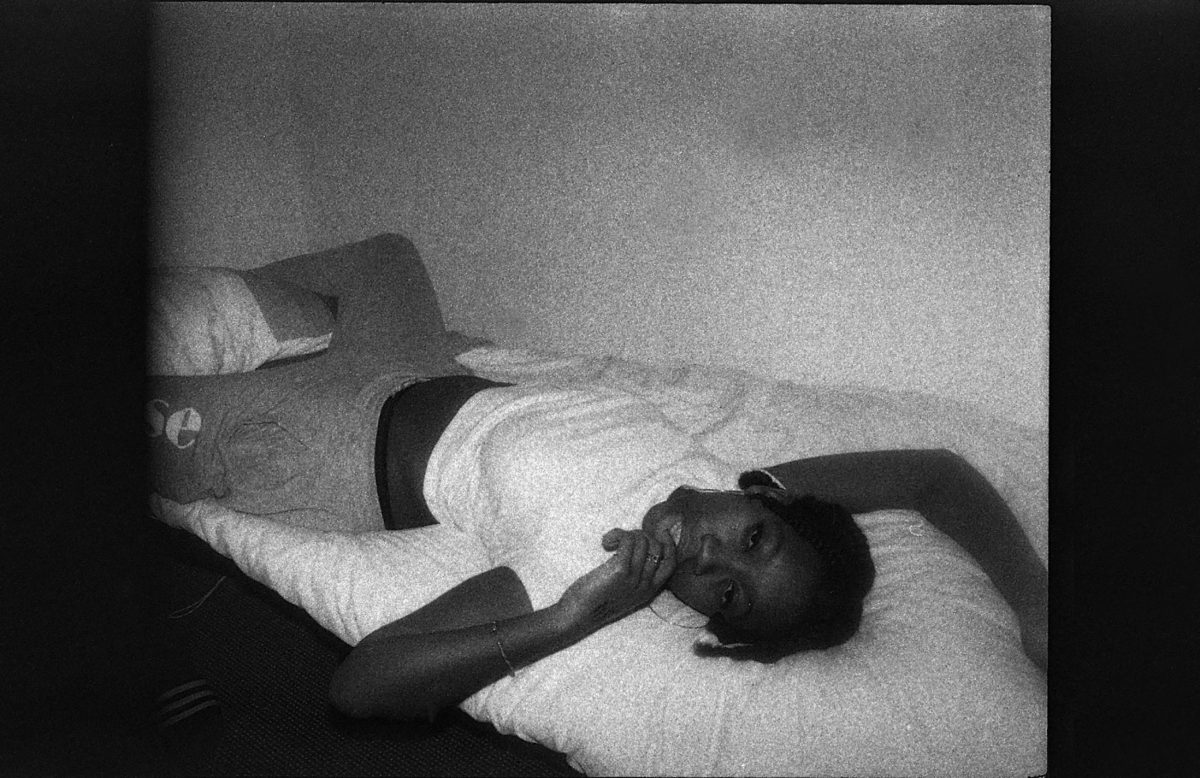

At the onset of the pandemic, London-based photographer and filmmaker Campbell Addy (usually accustomed to high-profile cover shoots and fashion editorials) began to informal document himself and his domestic surroundings as he adjusted to the first lockdown in England. “Although I loathed being idle, there’s beauty in stillness and life in the waiting,” he reflected

when sharing images from his nascent series with his Instagram followers last April.

As it unfurled, the project both stabilised and memorialised a disorientating period. As with photographs made in the pandemic by the likes of Bex Day, El Hardwick and Dana Scruggs, it also segued into an examination of selfhood.

As the once familiar pace of physical exhibitions resumes in pockets of the world, curators are transferring these personal experiments in image-making, largely confined to social media in the height of the pandemic, to tangible forums. When placed in group contexts, these works made in solitude are endowed with a new physical collectiveness that has been missing from life over the past year.

- Denisha Anderson, The Self Portrait at HOME, presented by Ronan McKenzie WePresent by WeTransfer

The Self Portrait, a group show held by London arts space HOME and online editorial platform WePresent, invited Black female photographers to turn the lens on themselves in an exploration of self. In her contribution, London-based creative Denisha Anderson chose to use Polaroids specifically for their candid feel, and incorporated elements present in her wider portraiture practice, such as nudity and domestic spaces, into her own images.

Her experience of lockdown was partly spent “reflecting on what’s going on across the world, how I empathise, relate or disconnect,” she says. Yet it was also a time to retreat inwards: “I only had myself to explore directly, and what I mean by this is asking myself challenging questions: ‘Who am I at this moment? What do I want to share? Who is this for? And why am I doing this?’ The more I challenge myself the more I grow.”

This wasn’t the first time Anderson had experimented with self-portraiture, having previously used it as a vehicle to examine everything from her own appearance to western beauty ideals. However, her most recent self-portraits saw her strip back her presentation of herself even further. “No gimmicks, just me,” she reflects. “Who I am is enough so what I captured is me at my purest, as I explore my culture, heritage and in between.”

“No gimmicks, just me. Who I am is enough so what I captured is me at my purest”

For others in the exhibition, acting as both photographer and sitter was largely uncharted terrain, and with that comes a fresh layer of tenderness. Such was the case with Christina Ebenezer (who reclines on a sofa in her portrait, the shutter release in her hands a convincing double for a TV remote), and Adama Jalloh (usually to be found shooting black-and-white portraits of the communities that surround her, but now herself standing poised behind her camera in an empty studio). The quietness of these portraits, together with the conspicuous placement of their tools and the intimacy of their surroundings, is suggestive of proximity.

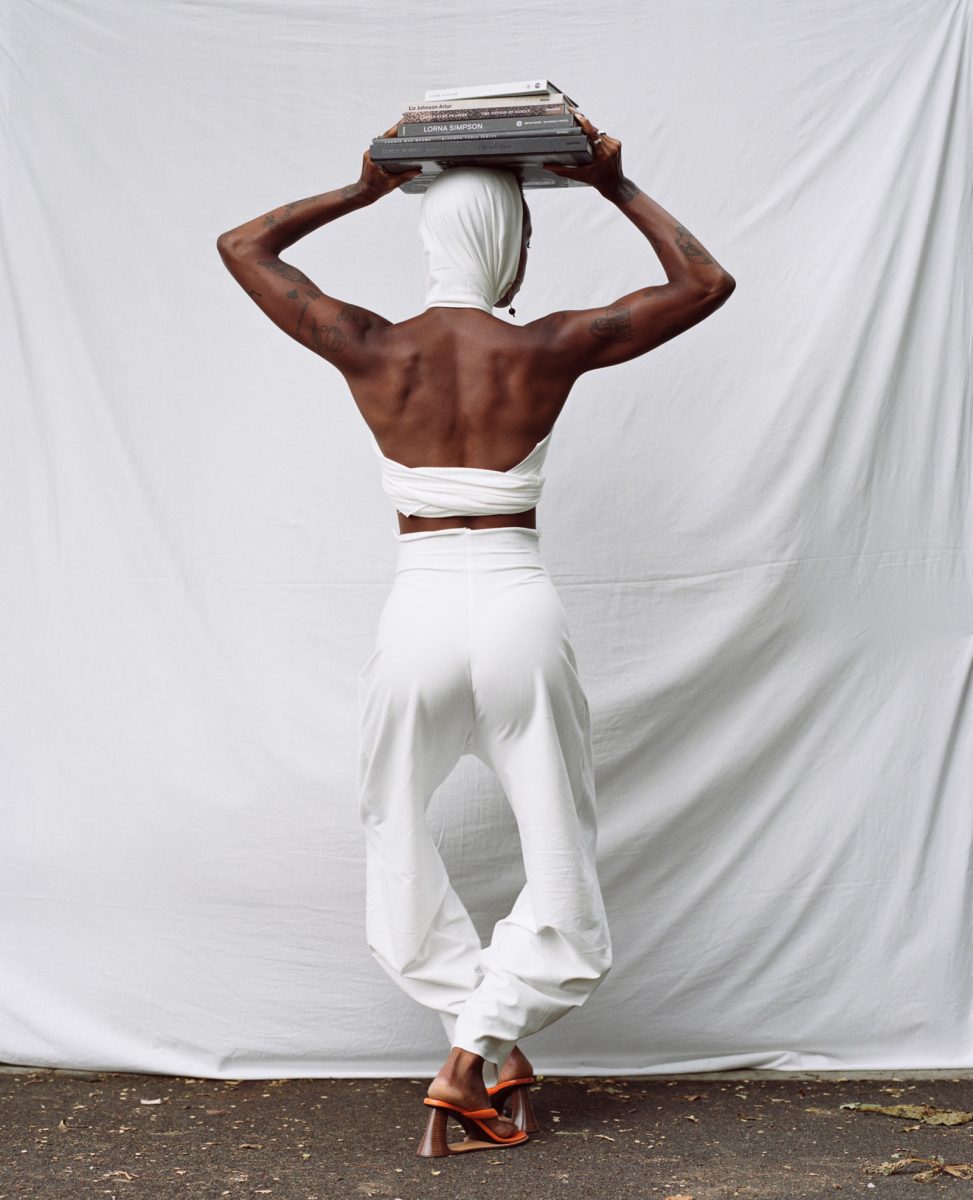

The show, according to the gallery, is an “act of self archiving”, demonstrated in its very creation, as well as in the tools and materials these photographers leave visible in the images. In the triptych created by Ronan Mckenzie (also the founder of HOME and the show’s curator), a stack of monographs (among them works by Zanele Muholi, Carrie Mae Weems and Liz Johnson Artur) forms an extension of her physical body, contextualising her artistic identity and connecting her to a wider creative archive.

- Left: Widline Cadet, Èske w Kòmanse Kote Mwen Fini? (Do You Begin Where I End?), 2020. © Widline Cadet; Right: Seremoni Disparisyon #1 (Ritual [Dis] Appearance #1), 2019. © Widline Cadet

For audiences currently engaging with pandemic-era projects, particularly in the seemingly novel environment of a gallery space, such exhibitions may give rise to a retrospective feelings, drawing a dividing line between then and now. However, a collection of five solo exhibitions in Bristol clings onto the sense that, like the everyday conditions we live under, many works and the experiences they contain are continuously evolving. Brought together under the banner In Progress, the group show at the Royal Photographic Society presents ongoing projects and the typically private realm of research and process behind them.

“When the pandemic first began I spent months not creating any new work. I didn’t even pick up my cameras recreationally”

Among the exhibitors is Haiti-born artist Widline Cadet, whose practice considers themes such as migration, memory, and Haitian culture relative to the United States. On show is her personal series Seremoni Disparisyon (Ritual [Dis]Appearance), which expresses Black womanhood and the multiplicity of identity through a surreal outlook.

The project comprises self-portraits (sometimes symbolically, with the inclusion of stand-ins), yet its presentation is made all the more personal in the display of the materials that fed into it: the website tabs, video chats, bell hooks excerpts, and essay texts strewn with pink highlighter.

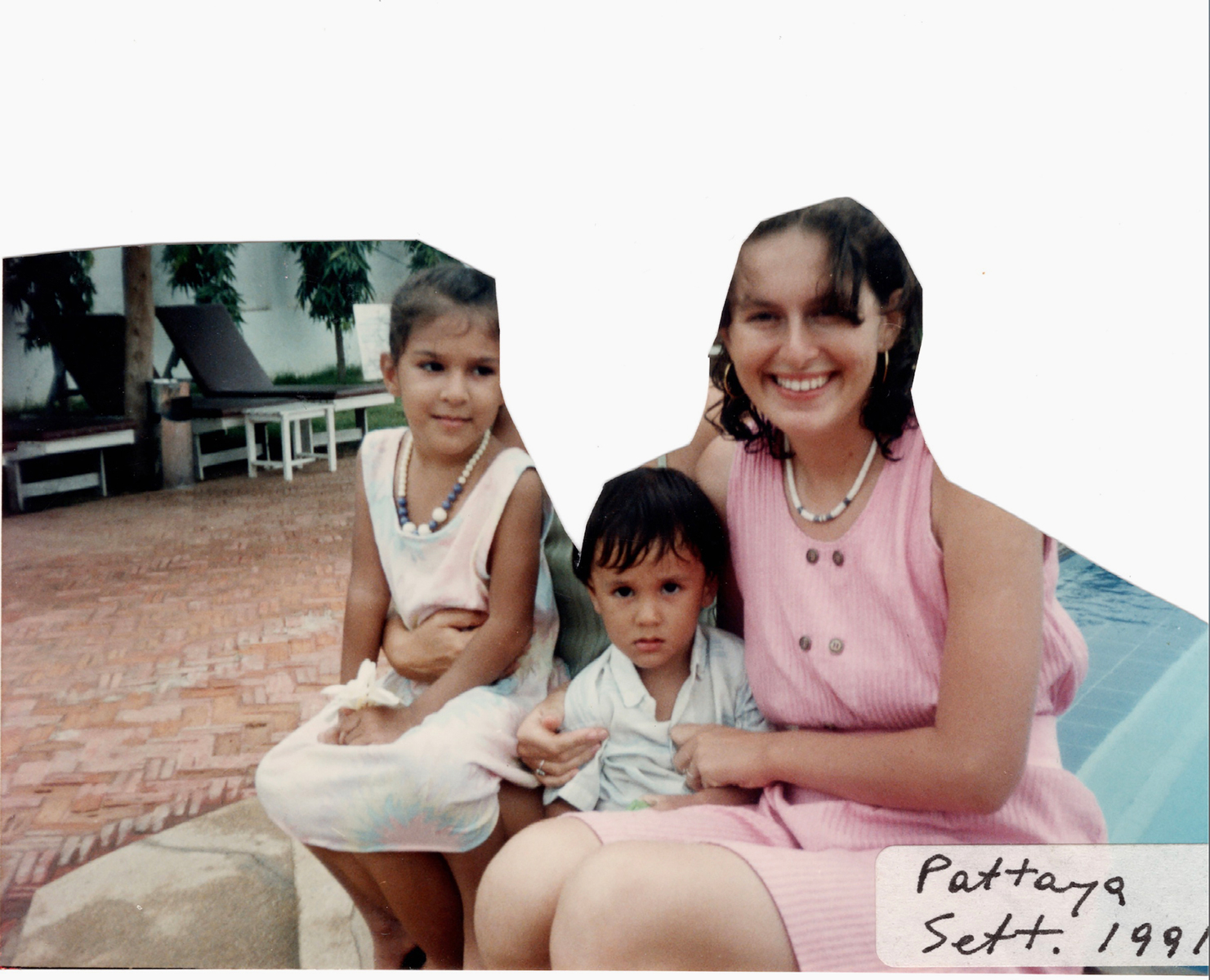

Elsewhere in the show, Bangkok-born London-based visual artist Alba Zari brings the complexities of her family history to a public stage with her project Occult, which explores her roots in the religious sect she was born into. “Due to the nature and focus of my works, they have, and will always continue to remain extremely personal,” says Zari, who previously investigated the father she never met in her book project The Y.

Alongside her own original images, Zari presents archive materials and family photographs, gateways to times gone by that, for many of us, beckoned for our attention in this period of isolation. “I feel that all the time I had during lockdown was a gift,” she explains.

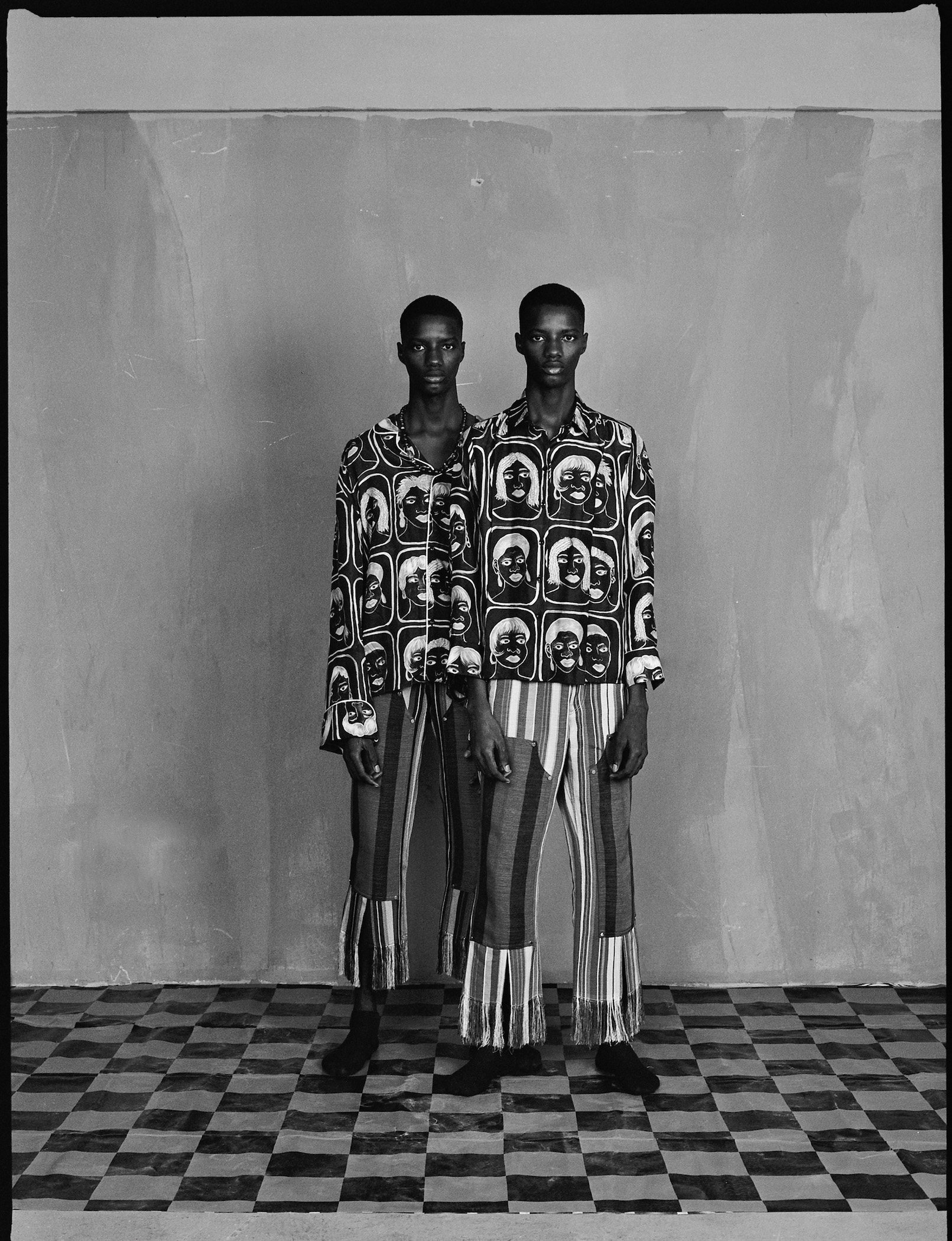

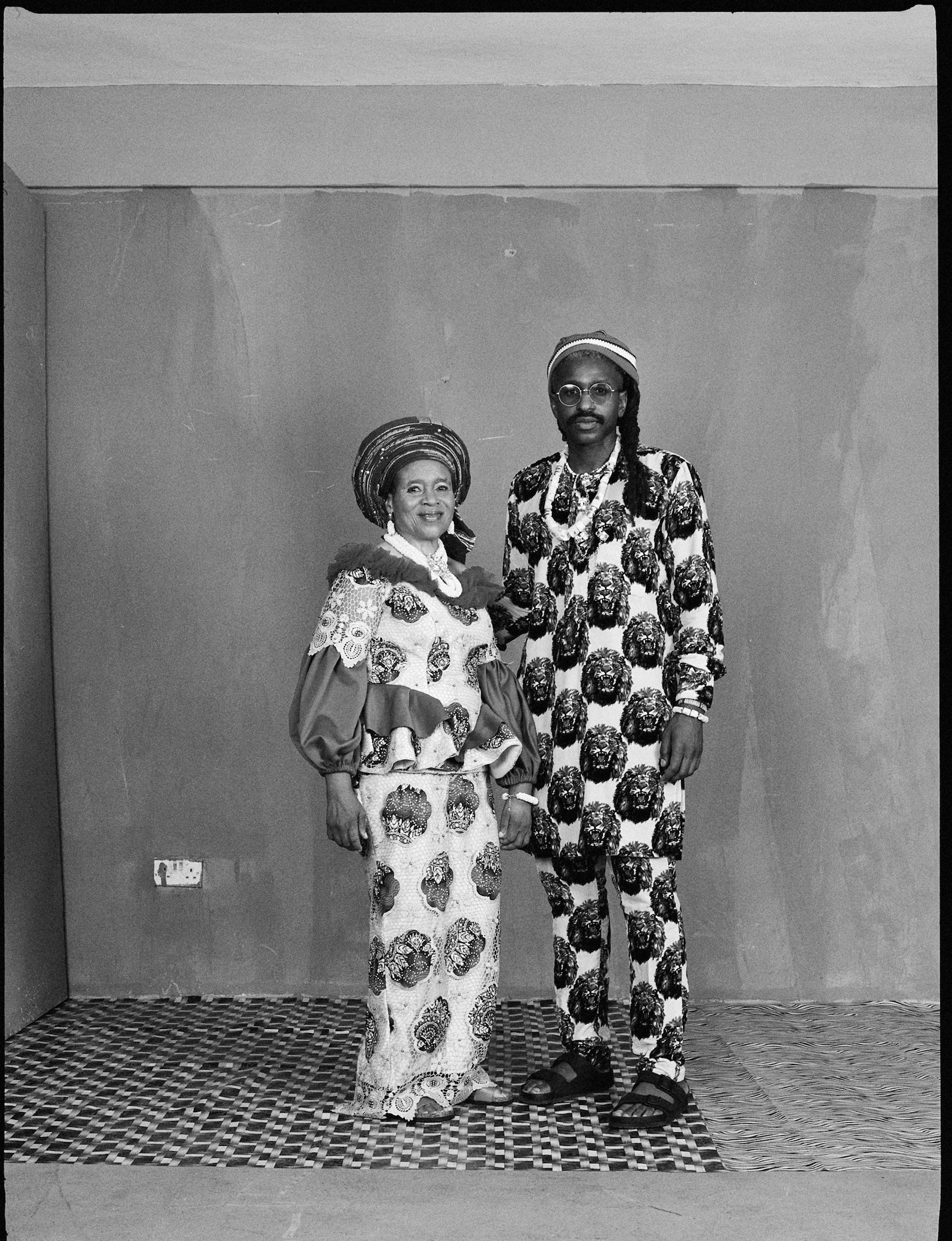

Retracing family relationships is similarly a central part of Brad Ogbonna’s personal work. In the years since his father’s death, he has been constructing a visual narrative as a means of sustaining a dialogue both with his late father and with his forebears in photography. His most recent images in this body of work, part of a forthcoming exhibition at New York’s International Center of Photography, branch into even more personal waters following his experiences of last year. “When the pandemic first began I spent months not creating any new work,” he recalls. “I didn’t even pick up my cameras recreationally.”

Brad Ogbonna, Paul & Peter, 2021. © Brad Ogbonna

Ogbonna didn’t reconnect with photography until the death of George Floyd. “I felt overwhelmed and perturbed by the reality that I was now experiencing,” he says. “The lack of justice and leadership, the daily protesting, the response and lack thereof from peers, seeing my hometowns of Minneapolis and Saint Paul ablaze, and not knowing at first where my place in all of it should be.”

“One of the things that I felt had been missing from my own body of work was a focus on my own life”

Ogbonna remembers searching for “space and the semblance of peace” in upstate New York and Long Island: “Focussing on self-preservation and seeking the idyllic became an escape for me and informed a lot of the work I was creating at that moment.” It was a period defined by introspection as both individual and photographer, leading him to look closer to home in his work.

“One of the things that I felt had been missing from my own body of work was a focus on my own life: my mother and my family, our culture,” he explains. “After being away from my closest family members for more than 16 months I felt the fear of loss and being disconnected.”

“I feel that all the time I had during lockdown was a gift”

The conditions of the pandemic have been a “constant reminder of the speed and fragility of life,” he says, and his experiences are manifest in his most personal work to date. “I wanted this body of work to be reflective of the present, the past, and to leave something behind for whoever comes next.”

The preservation of time in a motionless period also finds its way into Golden Apple of the Sun, the new book by writer and photographer Teju Cole. Freezing moments as we ourselves are physically, geographically frozen, the book brings together still lifes that Cole photographed routinely and repetitiously from his kitchen in Massachusetts in the weeks prior to the 2020 US presidential elections. Resisting the temptation to arrange his countertop, Cole’s lens lands upon haphazard remnants of daily life: cutlery and crockery in various stages of use, crumbs and citrus fruits.

In the book’s closing essay, Cole’s ruminations on art history and the politics of food are punctuated by diaristic interjections that mirror his unfiltered imagery. “Rather than asking what I can do to manually organize the given into a picturesque scene, I shift the question to one of what the kitchen looks like right now, asking that question day in, day out, attempting to find out if a photograph that interests me is possible in those conditions,” he writes.

The familiar rhythms might have been rubbed away over the course of the pandemic, but many photographers looked inside and found new ones. As Campbell Addy says, there is life in the waiting, and there is art, too.

Megan Williams is a staff writer at Creative Review