Suspended from the ceiling of Candice Lin’s recent exhibition, a beaked bird figure reminiscent of a 17th-century plague doctor is an unsettling sight. The leather mask conceals a virtual-reality helmet that offers visitors an alternative view of the artist’s major solo survey, Pigs and Poison, which premiered at New Zealand gallery Govett-Brewster in August last year before traveling to the Times Museum in Guangzhou more recently. In this distorted reality, the gallery space becomes a desolate, apocalyptic world littered with industrial debris. A trebuchet hurtles ‘flesh lumps’ while silhouettes drawn from 19th-century racist political cartoons remain just out of focus in the shadow of the viewer’s peripheral vision.

“I was interested in the fantasy and projection of disease and the way that medieval imagery is encountered by us nowadays, which is often through the lens of Renaissance fairs or video games,” explains the Los Angeles-based artist. While there’s a sense of grotesque comedy as these (virtual) bloody carcasses of indistinguishable origin land with a thudding quiver at your feet, it’s a jarring reflection of our extraordinary times.

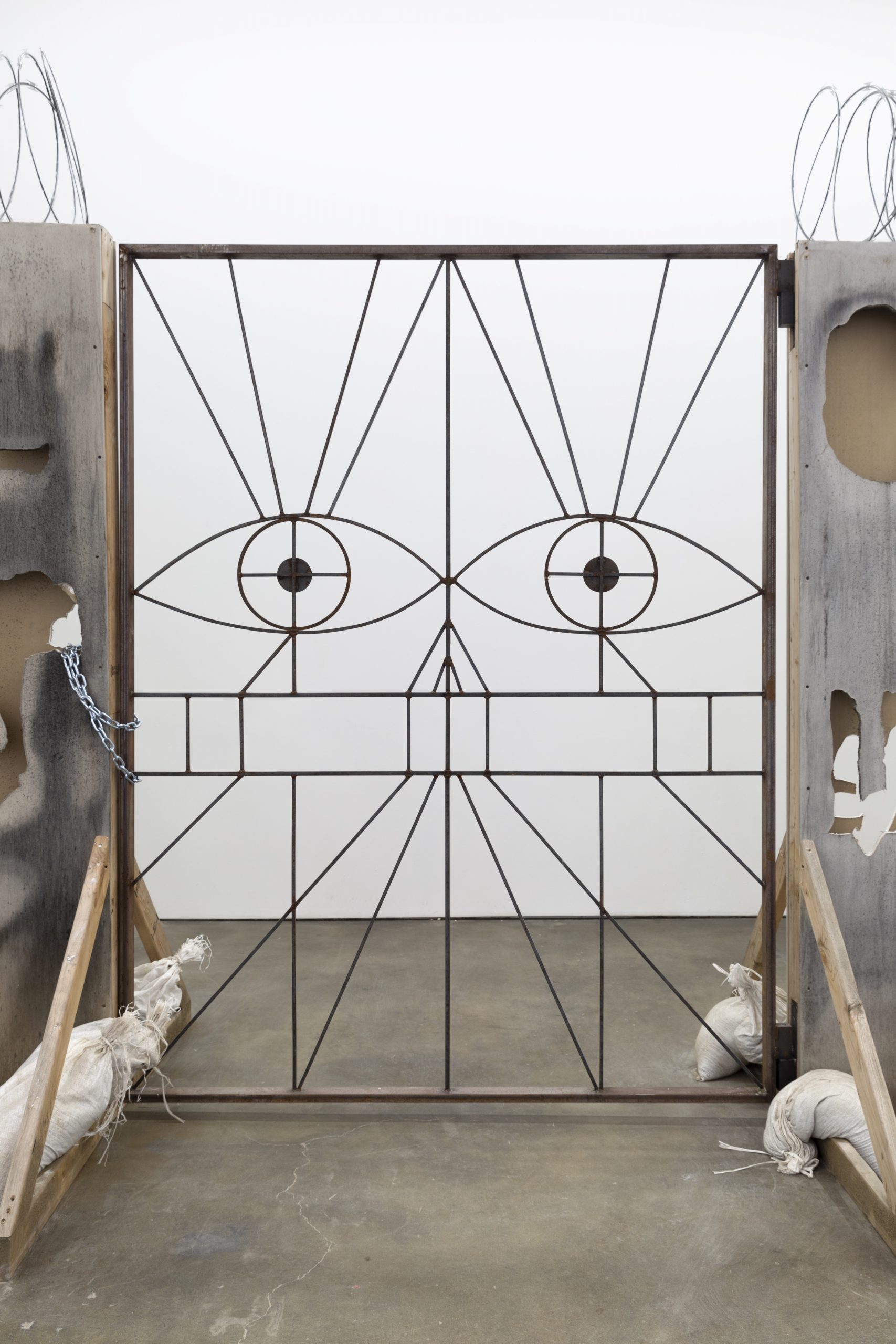

That Lin’s newest body of work parallels the current Covid-19 pandemic is entirely coincidental: the exhibition is the culmination of several years of research that the artist undertook into 19th-century Chinese indentured labourers (also known as ‘coolies’), an interest that was prompted by Lisa Lowe’s book The Intimacies of Four Continents. Spanning painting, sculpture, VR, textiles and drawing, Pigs and Poison was originally set to debut at Spike Island

in Bristol before the coronavirus crisis unfolded. It will now open there in February next year instead.

“The artist replaces linseed oil (traditionally used in oil paintings) with wax, pigment, and lard”

Lin’s research surfaced all-too-familiar narratives of ethnic tensions and anti-Asian violence surrounding epidemics. Officials in Honolulu quarantined and burned the city’s Chinatown during a bubonic plague outbreak at the turn of the 20th century, while politicians in San Francisco similarly funded a “full sanitation campaign” of its own Chinatown, in addition to restricting the movements of Asian immigrants travelling in and out of California. The artist draws attention to the national anxieties around disease and contagion and how they continue to shape US immigration policies to this day.

Lin grew up in Portland and has been living in Los Angeles since 2005. Represented by François Ghebaly gallery, she has exhibited at the Banff Art Center (Canada), Galeria Quadrado Azul (Portugal), Moderna Museet (Sweden), among others, and has her first US museum solo show at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. Through her multidisciplinary work, Lin interrogates colonialism, migration, marginalised histories and the racialisation of disease and contagion.

“There’s a sense of grotesque comedy as these (virtual) bloody carcasses of indistinguishable origin land with a thudding quiver at your feet”

At the core of the Brown University graduate’s research-based practice is a voracious appetite for the materials and craft processes intertwined with these complex legacies. “Candice is very carnivorous, in the sense that she will work with anything,” says Spike Island director Robert Leckie. “She’ll go to laborious lengths to make work happen.” To wit, Pigs and Poison includes a large paper work that Lin handmade by boiling the fibres of sugar cane, yucca, cotton pulp and poppy stems with indigo (all plants that have their roots in 19th-century indentured labour). There’s also a “purring” sculpture crafted from encaustic wax, resin, wire, paint and fibreglass.

Elsewhere, the artist replaces linseed oil (traditionally used in oil paintings) with wax, pigment, and lard. “I wanted to use lard to talk about both the kind of racial animalisation of these labourers but also the way that animal histories are interwoven with human histories as well,” says Lin. “I was thinking about how the material of the artwork, rather than the representation it depicts, could hold some of that history.” Similarly her interest in lard stems from the term ‘pigs’ that Chinese labourers were pejoratively known as due to their long braided queues (the other half of show’s title, in fact, reflects the opium trade).

“In this distorted reality, the gallery space becomes a desolate, apocalyptic world littered with industrial debris”

Lin is currently preparing for the Prospect New Orleans biennial, researching the Slaughter-House Cases—a landmark US Supreme Court decision of 1873 that upheld a Louisiana law restricting slaughterhouse operations in the city to a single corporation—and the way that animal byproducts and carcasses were entangled in a legal case around citizenship and economic privilege. Again, the artist is immersing herself in a centuries-old technique, this time enfleurage, a process that involves infusing fats with the delicate scent of flowers. She will be making a “scented lard” work that people will be able to put on. “I am drawn to the material [of lard] for its historical resonance,” she adds.

There has been much talk about and reflection on how much the Covid-19 pandemic has altered the world over the past 18 months—yet Lin’s work shows how the same painful tropes echo throughout history, demonstrating the way in which immigrants are forever seen through the lens of “the other”. Is history destined to repeat itself? Or is it simply because inherently racist societal constructs fundamentally restrict us from forging a new path? Crises should unite us, yet they’ve consistently divided. Pigs and Poison is a stark reminder that even when the world can seem completely different, nothing truly ever changes.

Jess Klingelfuss is a writer, editor and photographer specialising in contemporary art, design, travel and lifestyle

Installation photography by Ian Byers-Gamber; individual works by Ian Byers-Gamber. All courtesy the artist and François Ghebaly