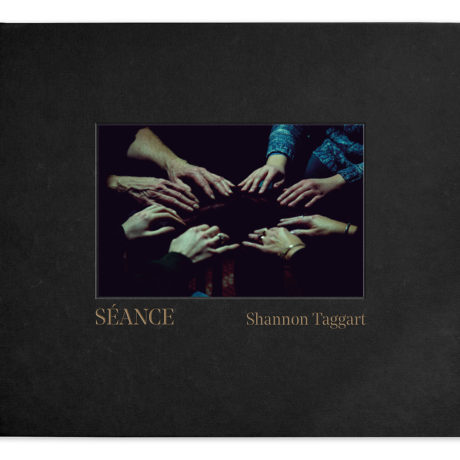

How do Destiny’s Child contact the dead? They have a Séyoncé. Jokes, and associations with teenage sleepover ouija board dabbling aside, séances obviously have a fascinating, if spooky, history. But until seeing this fascinating book of photographs by Shannon Taggart, simply titled Séance, I was quite ignorant of the prevalence of the practice today.

“Whatever its origins, there has been no shortage of artists inspired by the ideas of Spiritualism”

Taggart has spent the last eighteen years documenting contemporary Spiritualism, a religion that originated in America in the mid-nineteenth century and believes in communication with spirits of the dead. Brooklyn-based Taggart was, somewhat unusually, given access to the Spiritualist communities of Lily Dale, New York and The Arthur Findlay College in Essex; and her candid, strange and occasionally rather sweet images offer an insight into previously undocumented communities.

Presented alongside archive imagery including photographs, artworks and book spreads dating back to the early twentieth-century, her work shows that both the nature of the Spiritualist communities, and the processes they use, are remarkably similar to those when the practice first came to being in 1848 in Hydesville, New York. That year, sisters Kate and Margaret Fox reported that they had made contact with the spirit of a dead man who was buried under their house; saying that they’d heard him tapping on things. Although there was no record of a body having been found, and four decades later the sisters admitted the whole thing was a hoax (an admission they later retracted); the idea of actively seeking to commune with the dead quickly caught on and became an unlikely part of early American cultural ideologies (though largely among the middle and upper classes.)

Whatever its origins, there has been no shortage of artists inspired by the ideas of Spiritualism. Among its most famous proponents is Swedish artist Hilma af Klint, who belonged to a circle of women called The Five who frequently took part in séances together. Her abstract paintings are widely seen to be informed by her interest in spiritually; and among her Modernist peers who shared an interest in such matters (though not to such a stated extent) are Wassily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian and Kazimir Malevich, who drew inspiration from the related Theosophical movement. This billed itself as an “unsectarian body of seekers after truth, who endeavour to promote brotherhood and strive to serve humanity” through explorations of matters such as Occultism and the Western esoteric traditions of Hermetic Qabalah.

Spiritualism has long played a role in the practice of Taggart, too: as a teenager, her cousin claimed to have received a message offering details of her grandfather’s death from a medium. A decade or so later, in 2001, when working as a photographer, Taggart decided to shoot some images of where her cousin received that message, the aforementioned Lily Dale in New York, where the world’s largest Spiritualist community is based.

“The images veer from very haunting and eerie to the sort of cute snaps you’d find in your mum’s dusty, stashed-away photo album”

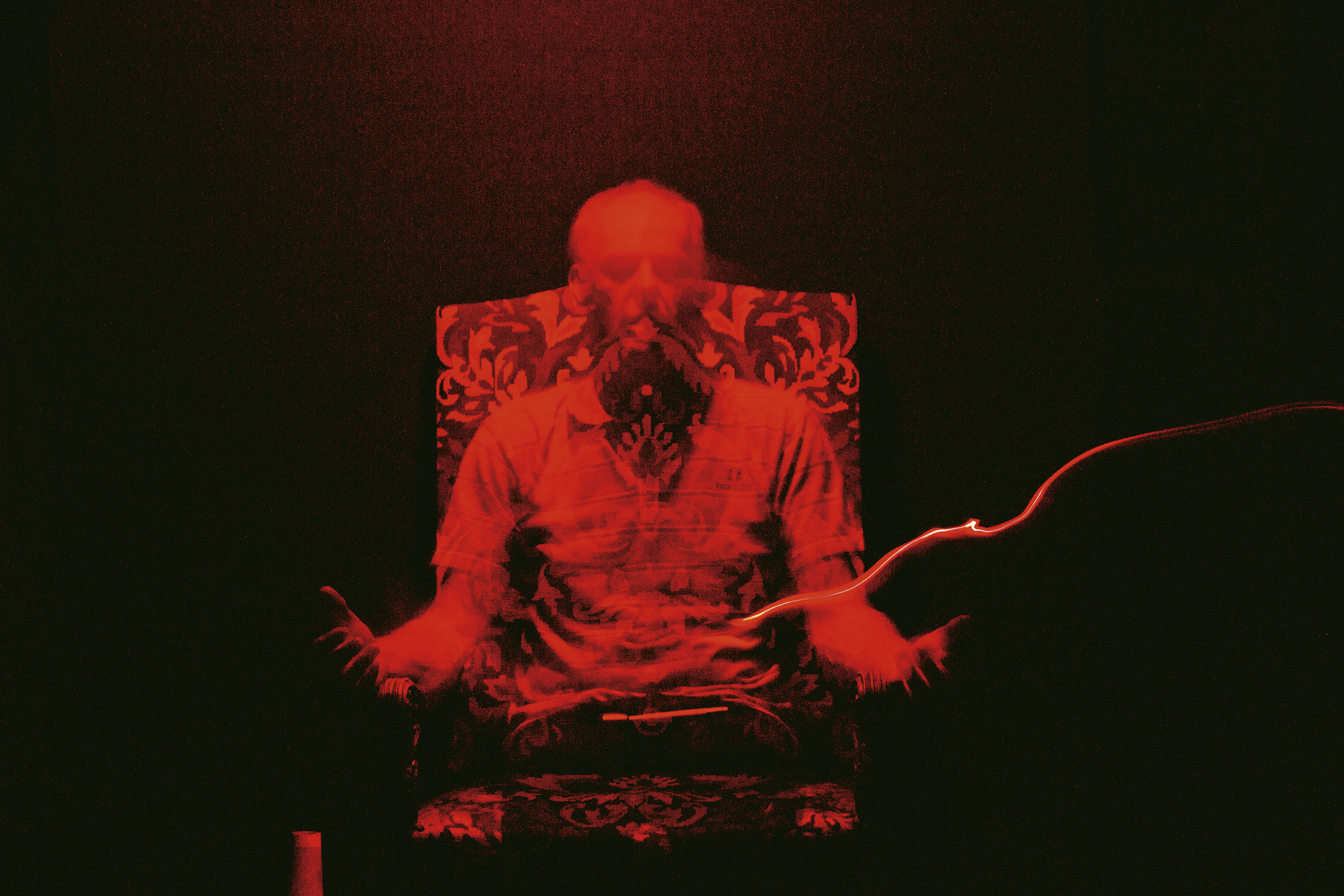

The photographer initially set out to spend a summer there but ended up revisiting such communities over almost two decades, simultaneously learning about the religion and its followers and gradually telling those stories photographically. She ended up spending years traveling the globe searching for “ectoplasm”, a substance defined as “supernatural” and viscous, “that supposedly exudes from the body of a medium during a spiritualistic trance and forms the material for the manifestation of spirits”.

Séance showcases 150 of Taggart’s images alongside her own commentary on her experiences, as well as a foreword penned by Ghostbusters creator Dan Aykroyd, who it turns out is a fourth-generation Spiritualist himself.

The images veer from very haunting and eerie to the sort of cute snaps you’d find in your mum’s dusty, stashed-away photo album of Butlins holiday snaps from the eighties—all gaudy colours and people seeming to have a good time. Whatever your stance on all things ghostly, the book is utterly compelling: the images alone tell a thousand stories. Augmented by a beautiful use of typography and carefully considered layouts, the complete package has the feeling of both a historical document and a sociological study on a contemporary culture that most of us had very little idea about.

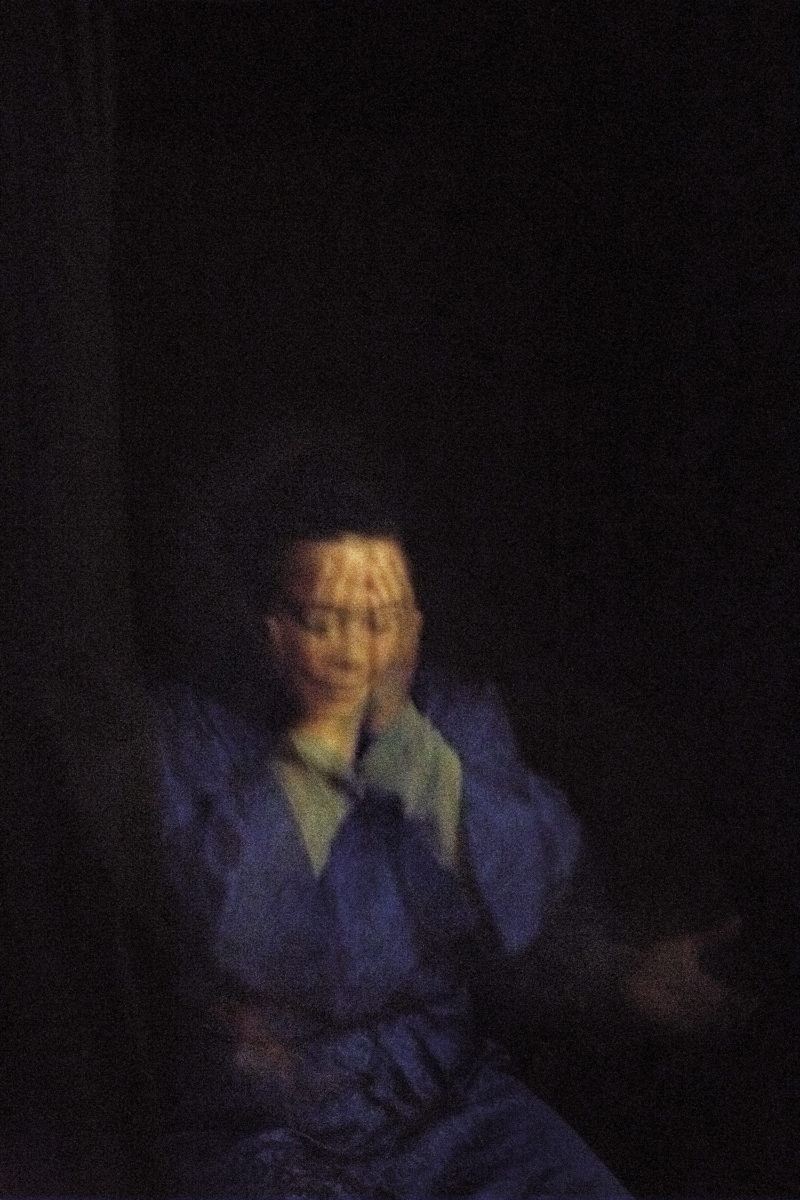

- Medium Sylvia Howarth enters a trance, England, 2013. From Séance by Shannon Taggart

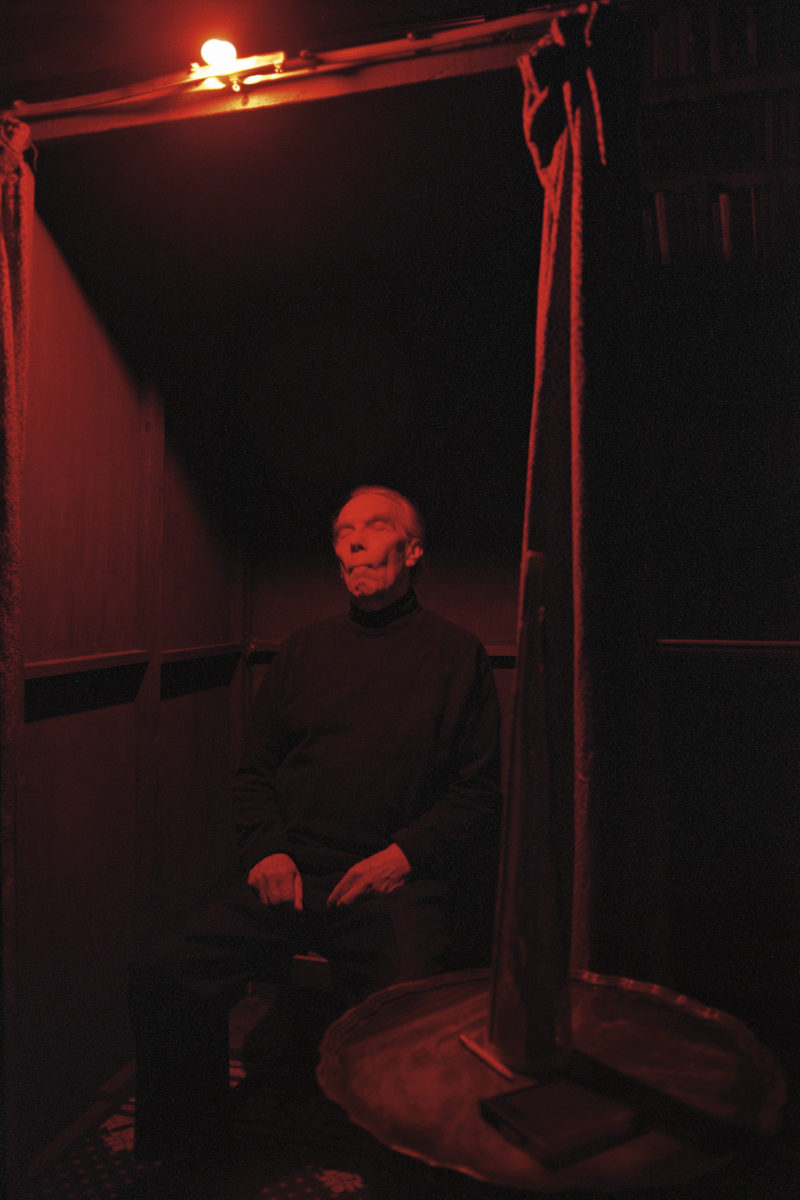

- Student in the medium’s cabinet, Arthur Findlay College, England, 2003. From Séance by Shannon Taggart