“Oh, having one child isn’t the real motherhood experience,” a mother of two recently told me, a good old slice of unsolicited opinion. “You’re in this capitalist bubble with one. But two kids, that’s the real deal,” she proclaimed.

There are, it seems, some strict and unspoken codes about how many children is acceptable in this day and age. Environmentalists and anti-natalists will say none—in this line of thinking, children are seen as mere carbon footprints. On the other hand—and often without taking into account a mother’s health, age, fertility or desire—there is also the common expectation that once you do procreate, you have more than one.

“In the West, families of four or more children are generally frowned upon”

While women with many children are sometimes seen almost as feminine goddesses or “supermums”, more often than not they are seen negatively. As Dean Burnett wrote in the Guardian on the subject of how many children are socially acceptable, the answer seems to be two. “Having a supposed big family makes you a target for much criticism, with accusations ranging from being irresponsible to self-indulgent and more.”

As another article in The Week points out, our idea of how big our family should be is dictated by cultural norms. In the West, families of four or more children are generally frowned upon—a sign of poor education or poverty, or else a stamp of status for the wealthy elite.

How quickly you have your children and the age gap between them is also a contentious topic; I recently watched one impossibly fresh-looking mother being eyed up and judged at a children’s music group as she cared for her two children, a boy and a girl, fifteen months apart. “But… your hair is clean?” One mother exclaimed. “I mean, I’m looking at you and it’s terrifying,” another chipped in. “Only fifteen months apart!” The mother in question didn’t seem to take much notice—she was, after all, busy running after a toddler with a baby strapped to her chest.

The law in the UK also believes we should have two children—after that, you’re slapped with a tax. Families with many children are held up as freaks. An article in one UK tabloid recently announced the imminent arrival of the twenty-second child for the UK’s largest family, the Radfords. The matriarch, Sue, had her first child at fourteen. Now, aged forty-four, she is expecting another girl, due in April 2020.

A Radford size-family isn’t exactly common, but as we start families later and have fewer children—in August, the BBC published reports that the birth rate in England and Wales was at a record low—will the social policing of fertility continue?

“As we know, but too often forget, fertility isn’t something women have control or authority over”

At London’s Richard Saltoun gallery last week, guests to the opening of Matrescence, curated by Catherine McCormack, were invited to take part in Liv Pennington’s Private View (originally performed from 2002 to 2010 in London, and later at galleries in Manchester, Poitiers and Oslo) by taking a pregnancy test—the collective results projected in real time in a glorious statement about privacy and sexual productivity.

“Matrescence” refers to the process of becoming a mother—the physical, psychological, personal and political journey of a woman into motherhood—something that the exhibition (the first of a two-part exploration) seeks to explore through contemporary art, where wider society often leaves the issue unturned. Discussions of sexual productivity and labour all emerge in the exhibition, drawing on images that have become part of collective notions about fertility and reproduction; being bloody or barren, full or empty. The bodily experience, as the exhibition shows, rarely separates so neatly.

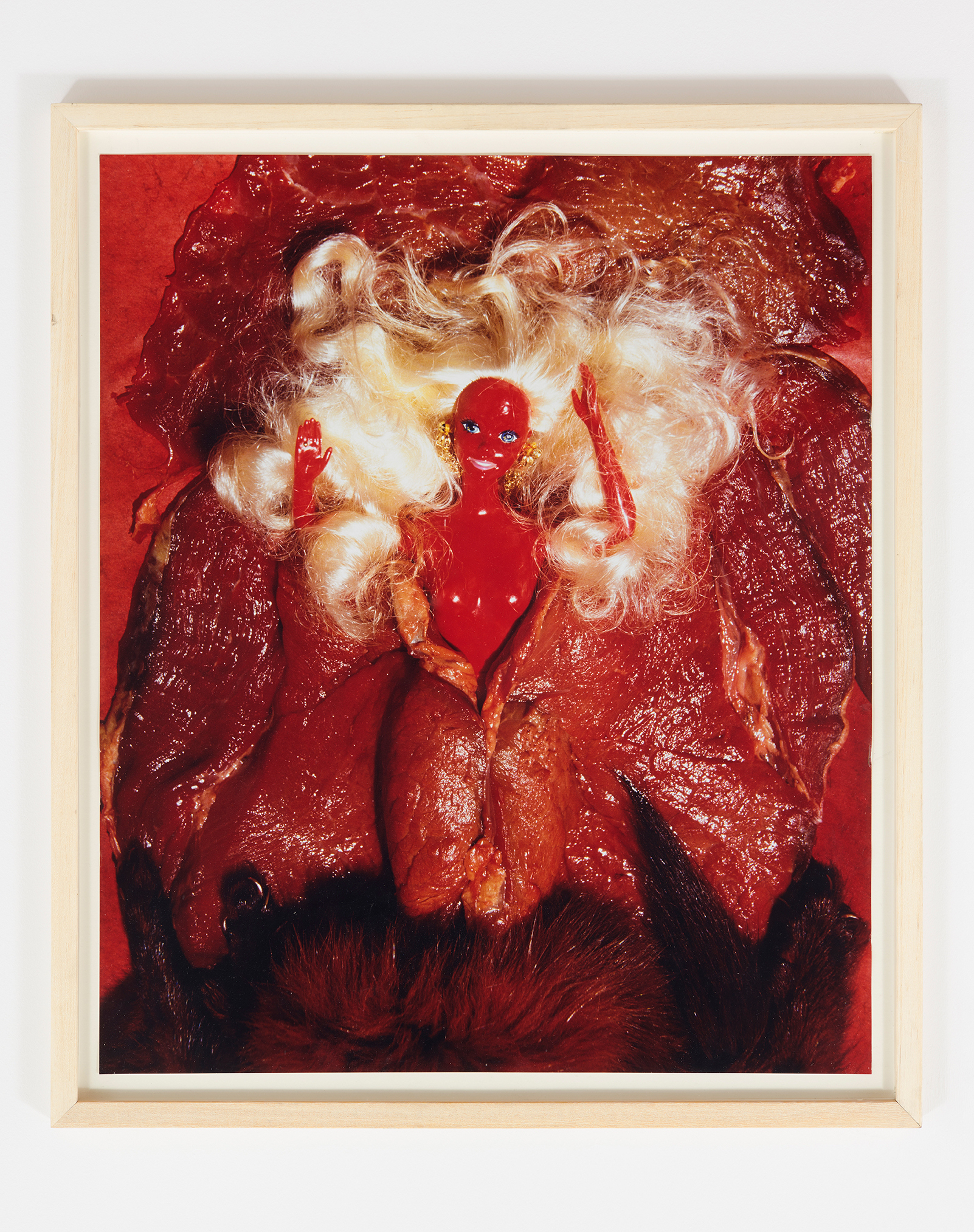

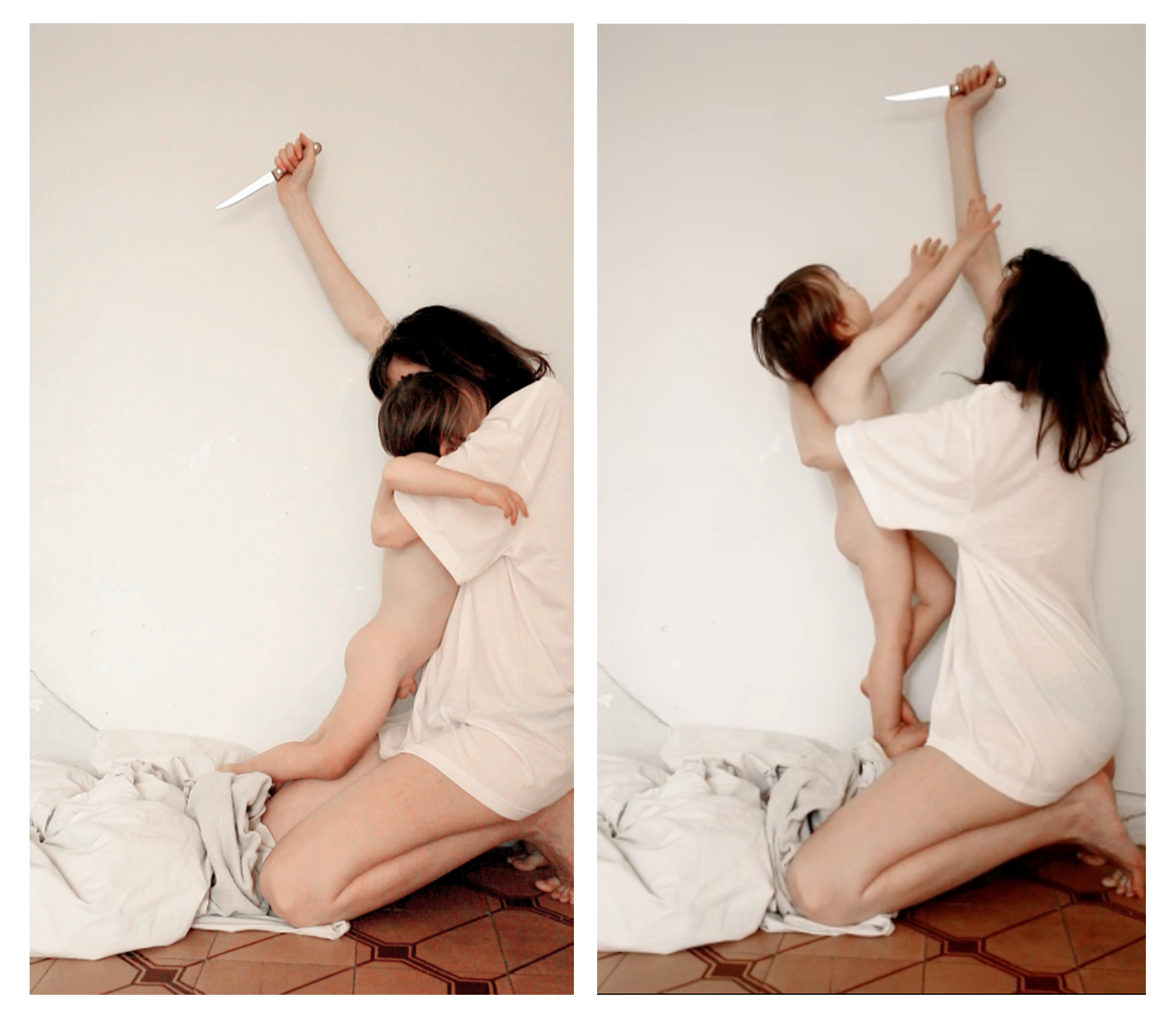

Included is the vivid, fleshy Birth of Barbie (1993) by Helen Chadwick, in which the blonde-haired plastic prototype emerging from a carcass of meat, shaped to resemble the vulva—a mirthful statement about the realness of the reproductive process and society’s squeaky clean portrayals of it—and Xiao Lu’s 2006 video work, Sperm, which is about the artist’s personal struggle with fertility after breaking up with her long-term partner and finding herself alone and wanting a child in China, where IVF is only permitted for married women. In Leni Dotham’s, Mine, 2012, a mother seems to turn on her own creation; posing wider questions about the fallacy around maternal instinct and control.

Having grown up with the benefits of a large family, and now being the partner of someone who is the second of seven, I have seen how people gasp and recoil, incredulously asking “How could they do that?” As we know, but too often forget, fertility isn’t something women have control or authority over. What works for one doesn’t work for all. It is often not a choice of how many children you have, how you get pregnant or when. And if we are grossed out by how fertile a woman is, it is a sign of something more sinister and insidious in our society.