Sticky floors, formica table tops and colourful stools lined up along the counter; bottles of ketchup, and the scent of the deep fat fryer. The American diner is a space so familiar as to have become part of a collective mythology, immediately recognizable regardless of where exactly it happens to be located. The warm, greasy embrace of the diner is where filling, well-priced food is served up and regular customers convene and rub shoulders with newcomers.

A symbol of America since its inception in the late nineteenth century, the rise of the diner as a national icon is due in no small part to its place in visual culture. From Twin Peaks to Seinfeld, When Harry Met Sally to Coffee and Cigarettes, it has played an enduring part in cinema and television over the decades.

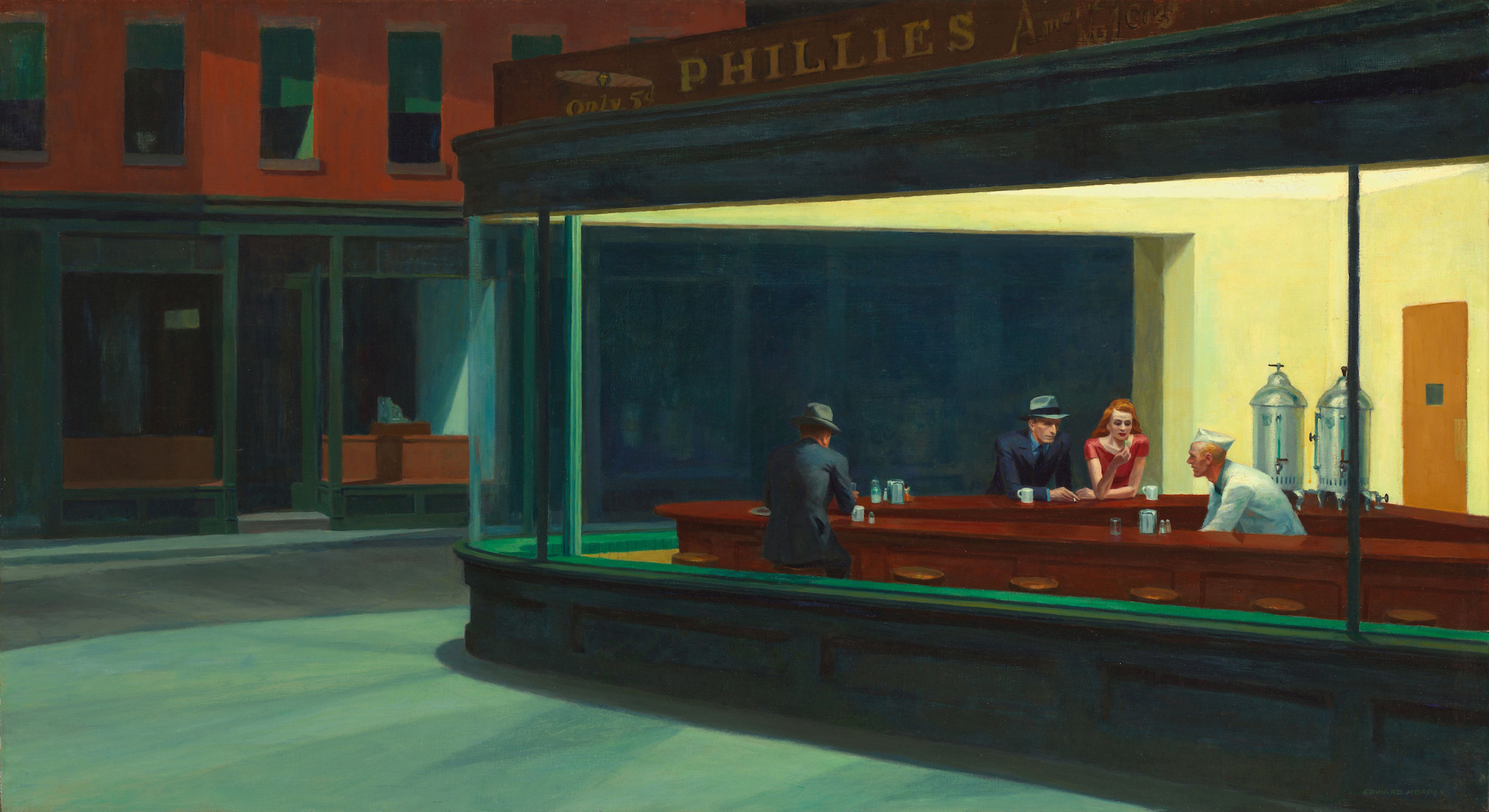

It was Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks that offered one of the earliest and most memorable depictions of a Manhattan diner in 1942. The glow of the warm light within, with just three of the stools at the central counter taken, came to evoke a particular feeling of urban isolation. The novelist Joyce Carol Oates once described the painting as “our most poignant, ceaselessly replicated romantic image of American loneliness”.

Shown at night, the incessant glow of the artificial lights outside the diner and within emphasize the strange conditions of the city, where so many people are able to live at close quarters without ever actually meeting. Olivia Laing describes it in The Lonely City as an urban aquarium and a glass cell, writing “Is the diner a refuge for the isolated, a place of succour, or does it serve to illustrate the disconnection that proliferates in cities? The painting’s brilliance derives from its instability, its refusal to commit.”

But is the diner itself necessarily a symbol of loneliness? William Eggleston has famously spent the last forty years ceaselessly documenting the underbelly of the American landscape in all its kitsch, seedy glory, from rusted motel signs to gas station pumps. A pioneer of colour photography, the artificial coloured plastics and wipe-clean surfaces that populate his images are ideally suited to the medium, with careful compositions often built around these colours.

“The American diner is a space so familiar as to have become part of a collective mythology”

In one image, condiments are bathed in the bright sunlight pouring through a window, while in another the deep red of the diner table and chairs appear to almost glow amidst the basic beige of their surroundings. Frequently devoid of people, the details of the chair left slightly pulled out, or the napkin set awry, hint at the many and varied lives of those who pass through these transient spaces.

Eggleston’s images share an affinity with Hopper’s in their engagement with the complex relationship between exterior and interior space. In Eggleston’s case, this means highlighting the contrast between cheerful diner and the often bleak landscape around them. His chromed diners sometimes sit as satellites in a wider desert landscape, with little but the wide-open road and electricity pylons for company.

There is surely nothing more evocative of the diner experience than sitting snugly in a booth, looking out of the window to the world outside. It is therefore little surprise that windows (or the light that they cast) feature frequently in Eggleston’s images of the diner—at once a barrier and a portal, from inside to outside, as exemplified by Hopper in Nighthawks.

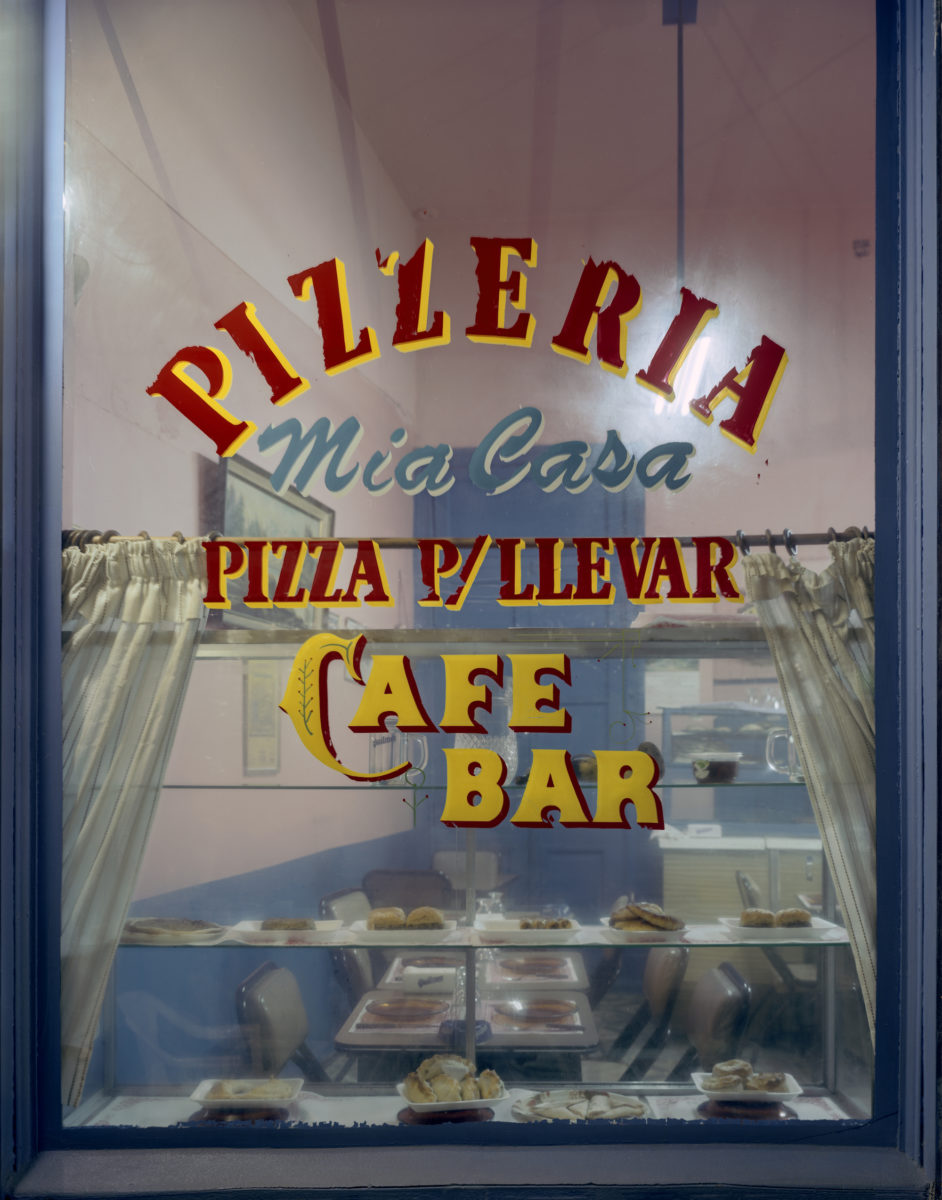

For Jim Dow, it is the layers of history built up over time in spaces like the diner that he looks to document, whether in his photographs of long-running restaurants, cafes, corner shops, sports stadiums, private clubs or even courthouses. The diner has been a recurring subject throughout his forty-year career, often shot on a wide-angle lens so as to contextualize the chromed stools and hand-painted signs.

“There is nothing more evocative than sitting snugly in a booth, looking out of the window to the world outside”

Unlike Eggleston, Dow zooms out rather than in, offering a clear-eyed portrait that allows the viewer to make their own judgement on these spaces. His images are not tinged with nostalgia; instead, they reveal the increasingly anachronistic aesthetic and function of the diner in an age of faceless chain restaurants and online food deliveries. While these diners are rooted in a sense of the local, with individual flair to be found in everything from the tiling to the menu design, Dow’s wider shots of their exteriors show them once again as lone beacons amidst a harsh, fast-changing landscape.

Jim Dow, Burger Orleans Drive-In at Night. LA 46, New Orleans, Louisiana, 1980. Courtesy the artist

Just last month, the New York Times ran an article with the headline, “New York’s Vanishing Diners”, and it has long been a source of contention amongst locals and tourists alike that these historic, community-focused eateries—cheap, cheerful and usually family-run—should be forced out by the relentless tide of big business and real estate developments.

An early influence on Dow was Walker Evans’s seminal book American Photographs (1938); he recalls the appeal of Evans’s “razor sharp, infinitely detailed, small images of town architecture and people. What stood out was a palpable feeling of loss…pictures that seemingly read like paragraphs, even chapters in one long, complex, rich narrative.” This sense of loss and longing is inevitably embedded in Dow’s own photographs of disappearing diners, entwined as they are with the changing face of America, complete with peeling paint, scuffed seats and faded signs.

But beyond the all-American fantasy of the diner, this is an eating model that has its roots in the diasporic heritage that the United States itself is built upon. From Greek to Italian, Mexican to German, the diner is constructed from a patchwork of culinary influences, and a rich social history of convivial dining.

Dow’s photographs of diners, cafes and other long-running eateries in cities across the world reflect this international influence. Whether in Buenos Aires or London, he finds common ground in their shared motifs: the gingham tablecloth, the glow of the neon sign outside, or the bottomless pot of coffee warming on the counter.

Monira Al Qadiri, The Craft, 2017. VHS video, colour with sound, 16 min. Co-commissioned by Gasworks and the Sursock Museum. Courtesy the artist. Photo by Andy Keate.

With a heritage of migration from all corners of the globe, the dominant ideal of the American diner as we now know it carries a charged set of associations—of cultural hierarchies and the erasure of individual heritage. These are some of the issues raised by Kuwait-born Monira Al Qadiri in The Craft, first exhibited at Gasworks in London in 2017.

“The diner is constructed from a patchwork of culinary influences, and a rich social history of convivial dining”

For the show, Al Qadiri constructed an imaginary American diner, complete with leatherette banquettes and checkerboard floor. Across, sculptures, video and sound works, she reimagines international diplomacy as an alien conspiracy, drawing a line of comparison between the arrival of the first American diner in her home country and an extraterrestrial invasion of sorts.

“As someone from Kuwait, it’s kind of taboo to admit to your own Westernization, but I want to confront it now,” she explained in an interview with The Quietus at the time. “The hamburger really became symbolic of American cultural expansion in the 1960s—that’s when it was cemented. But now, all of this—the high summer of the post-war boom—looks very obsolete and almost alien—like the Invasion of the Body Snatchers. It doesn’t really feel like part of our lives anymore.”

Junk food becomes symbolic for Al Quadiri of a wider political shift in the international dynamics that dictated the rise and rise of American cultural dominance and modern-day neoliberal ideals, of greed and globalization. “It’s always easy to critique the American influence on the world, imperialism and things like that. But I want to also show that I am complicit in it—and we all are. We took part in this junk food frenzy of capitalism. We were all a part of it.”

- Jim Dow, Gina’s Drive-In. US 2, Devil’s Lake, North Dakota, 2004. Courtesy the artist

Even if the diner itself is a dying breed, the image of the diner still holds strong, upholding a partly fictionalized vision of America—as portrayed by everyone from Raymond Carver to Martin Scorsese. Straddling fantasy and reality, loneliness and desire, the diner represents a refuge from the world outside—even just for the time it takes to a nurse a cup of hot coffee and a slice of pie. A legacy that has lasted into the present day, the future of the diner might be uncertain but its wide-ranging influence on popular culture and beyond remains unswayed.