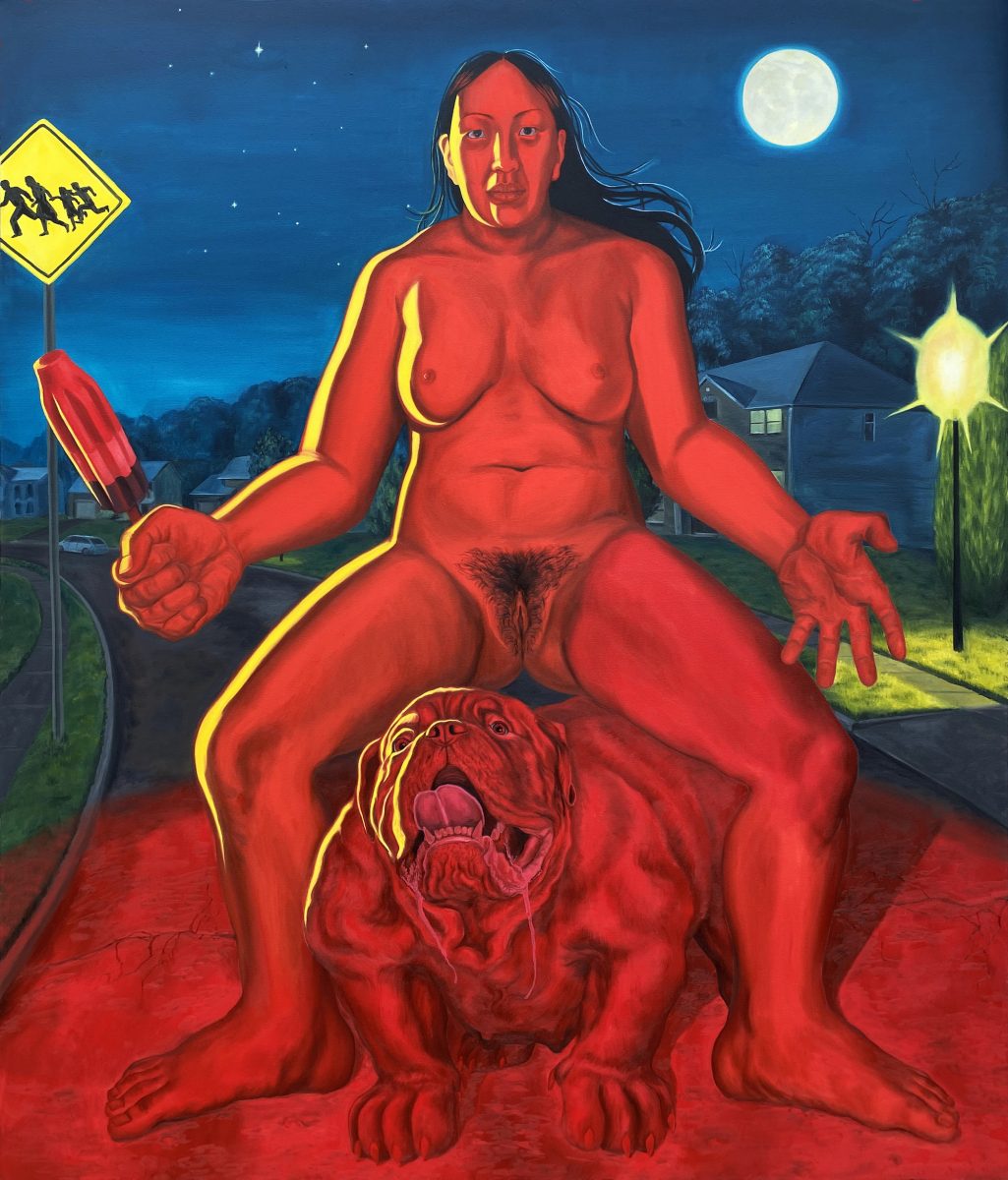

Moments of revelry, violence and desire collide in the confrontational work of Amanda Ba, whose vivid paintings amalgamate personal memory with darker fantasy. Animals and humans enact their basest instincts under the artist’s unwavering gaze, as nude skin and fur become one and the same. Folds of flesh seem to ripple sensuously in motion, as if pent-up energy were radiating across the canvas in a force-field of both anger and celebration. Social cues and inhibitions are let loose in these outbursts, while the repeated motif of the colour red casts Ba’s protagonists in an otherworldly light.

Born in Columbus, Ohio, Ba spent the first five years of her life with her grandparents in Hefei, China. This mixed heritage is never far out-of-sight in her work, in which Chinese symbolism meets contemporary scenes of domestic life. Ba paints Chinese subjects as a direct challenge to the predominantly white art history canon, while also grappling with her own status as a member of a diasporic community in the majority-white American suburb where she grew up. The result is a visceral expression of frustration, dual identity and reckless abandon.

Vivid red is a theme that runs throughout your paintings. What appeals to you about the colour, and what does it symbolise in the context of your work?

Broadly, red is a very powerful colour. It seems to have more emotional associations than any other colour—think passion, desire, lust, anger, love, fervour. It also has a range of symbolic associations throughout history, such as rebellion, war, health, religious devotion, and of course, communism (think Red Scare). It’s a very popular colour in national flags, including China’s and America’s. I’m not necessarily appealing to all of these directly every time I use the colour red, but I think that I (amongst many others) am attracted to red for these reasons.

I also enjoy using genuine cadmium red oil paint straight out of the tube. It’s the only colour that I really splurge on (all my other colours are cheap as hell). There’s an interesting colour theory thing that happens when you put two complimentary colours next to each other (I use red and green a lot in my work). The two colours vibrate against each other visually, especially if they are both highly saturated and of similar values. I like playing with how shades of almost supernatural green can vibrate against a vivid red.

“Red has more emotional associations than any other colour—think passion, desire, lust, anger, love, fervour”

Which film shows the world as you know it?

This answer is basic but the one that came the most easily to me is Chungking Express. Wong Kar Wai’s films had a huge influence on me when I started oil painting as a teenager, and I still often use his film stills as colour references for my paintings. Especially in In the Mood for Love—I think that ignited my obsession with red and green over other complimentary pairs (like blue and orange).

It’s obviously not just the colour optics though; it was also the optics of seeing relatable ethnically Chinese young adult characters on screen that gave me something to attach my aspirations and idolatry to. And Chungking Express in particular—who wouldn’t want to be Faye Wong? As I’ve gotten older I relate more and more to the way the characters drift about in dense and claustrophobic urban spaces, finding brief and fleeting moments of respite and grounded-ness.

The characters are solitary agents and do things for themselves and by themselves, sharing time when their paths cross and then departing once again, often without a full resolution. I’m currently at a point in my life where I’ve moved around so much and so often that I’ve embraced this solitary attitude and the opportunities it can bring. It’s a movie that has stayed remarkably relevant to me throughout my years of change.

How important is your Chinese heritage to your work, and what was your experience of growing up in Ohio as a member of a diasporic community?

It’s very important that I’m Chinese—I’ve come to realise that to occupy space in (and against) the Western Art Industry as an Asian American woman is a radical thing in itself. My fellow Asian American artists and I are writing an art history that challenges the white canon. I think this is a big reason that POC artists are reviving figuration in a huge way—we want to see ourselves represented, in bodily form, to stand up against the way that the Western cannon has bombarded us with white figures since the beginning. In my work I also draw a lot of influences from Chinese symbolism, and my narratives often reference events from my upbringing in China.

As for Ohio, I felt detached from my diasporic community and alienated from my culture in the suburbs. I grew up in ‘white’ white suburbia (white picket fence, jocks and cheerleaders, soccer mom vans), where all the Asian kids felt so much pressure to assimilate that it limited how much we could relate to each other. I’ve been reckoning with it ever since I got the fuck out of the suburbs, and I think some of that definitely comes through in my work.

“I’ve come to realise that to occupy space in (and against) the Western Art Industry as an Asian American woman is a radical thing in itself”

What are you most afraid of?

Artistically, I’m most afraid of creative stagnancy. You know that meme that’s like ‘galleries love a young emerging artist who can paint fast’? That’s exactly what I’m trying to avoid. I never want to get so comfortable in a style that it becomes formulaic and too easy to digest, and end up just churning out art objects. But that’s what a lot of galleries and collectors want to see. They love when you brand yourself fast and early. At some points I feel on the cusp of going full hermetic mode and not communicating with the outside art world at all for years, and then resurrecting myself alongside a completely new body of work.

Scenes of domesticity mingle with darker desires, sexual urges and animalistic impulses in your work. What are some of the influences behind these contrasting elements, and how do you seek to resolve them through your paintings?

I’m not looking to resolve anything. Each painting I make is an amalgamation of everything personal that’s on my mind at the time, from the authors I’m researching, to a dream I’ve had, to something from my past that I’m working through. Something I really enjoy is taking space from a work after I’ve completed it. The next time I go back to look at it, I begin to have deeper realisations about what I was actually going through at the time.

I spend a lot of time composing each painting like a thesis of sorts in the early preparatory stages, and they still surprise me with hindsight. I’ve always been a rather dark and perverted person, so I think it makes sense that my paintings lean towards the grotesque and the uncomfortable. I hope that others can pick out and relate to some of these facets of my work, and take it and use it for themselves.

Louise Benson is Elephant’s deputy editor