Masha looks cold. She’s chalky white with rosy cheeks and a shiny nose. Her lips are gently pressed together, and her eyes are glassy and wet like they’ve been leaking in the wind. She appears not to have any eyebrows, and her eyelashes are barely visible. She stands in front of a black backdrop, wearing a plain navy top and a dull yellow headscarf that’s tied up beneath her chin. Her left nostril is pierced with a tiny gold ring.

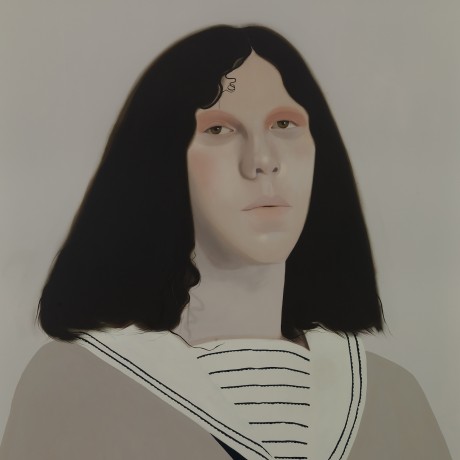

Masha’s is one of several faces that Sarah Ball has painted for her first solo show at Stephen Friedman Gallery in London. The British artist, who was born in Yorkshire and now lives in Cornwall, makes seemingly simple portraits that explore the gap between who we are and how we present ourselves to the world.

“It’s something I’ve always been interested in, the manifestation of our identity and the aesthetic choices we make,” says Ball. “I think it began when I was at school. I went to an inner-city comprehensive, and the emphasis wasn’t on education, we were much more interested in music. There was so much happening at the time, in the 1970s, from northern soul to punk to ska to disco, and all those genres came with a look; you could almost describe it as a uniform.”

We’re chatting over Zoom a couple of weeks ahead of her solo exhibition opening. Ball is speaking from her studio in Newlyn, a Cornish fishing town that (together with St Ives) became popular with artists in the late 19th century.

Behind her is another portrait heading to London: a pensive character with a soft black afro, the makings of a moustache, and thread-thin hoop earrings. I inquire about the sitter, and Ball replies, “I found Prudence on Instagram.” Social media is where she sources most of her images. She asks for permission before using them, and occasionally she and the subject end up messaging back and forth. “Some I keep in touch with, and a few I’ve painted more than once.”

“I’m obsessed with the way the figure can either grow from the ground or sit in stark contrast with it”

After graduating from art school in the 1980s, Ball worked in illustration for almost a decade. In 2005 she completed an MFA and returned to painting full time. “That’s when I became interested in biometrics, the reading of a face and physical features and how they relate to personality,” she says.

Each of the faces destined for the show defies conventional gender norms. “I’m interested in all aspects of the human condition, including sexuality and gender, which are intrinsic to our identity,” says Ball. With closely cropped compositions and muted backdrops, she zooms in on each sitter and the defining characteristics of their visual identities: a tattoo, a beauty spot, electric blue eyeshadow, a loose ringlet.

“I might be drawn to someone because of the aesthetic choices they’ve made, but it goes beyond that,” explains Ball. “I’m looking for empathy, and I’m looking at the gaze.” Her portraits are as much about capturing a feeling as a likeness. And yet, her style (meticulous, fresh, clear) is unsentimental. There’s emotion, yes, but also an absence. Physiognomy hints at a narrative without ever giving too much away. Pastel colours delicately suffuse each canvas.

“For me, they’re as much about the process of painting as they are about the person,” says Ball, who tends to make two or three portraits at once. This is partly because she wants the paintings to be in conversation with one another, partly (and more practically) because she works with thin washes of oil paint and needs to let each layer dry before adding another.

“I’m interested in all aspects of the human condition, including sexuality and gender, which are intrinsic to our identity”

After she’s found her subject, the act of making takes over. “I’m obsessed with the way the figure can either grow from the ground or sit in stark contrast with it,” she reveals. Ball is constantly striving for balance, which explains why some patches verge on overworked while others remain flat and abstracted.

Ball’s portraits exist in their own time and space. They have a stillness and a luminosity that make me think of Johannes Vermeer’s girls reading and writing letters, pouring milk, making lace. But instead of dazzling domestic scenes, her backdrops are free from distraction. At times they verge on surreal. “I think there’s quite a strong graphic quality to my work, and I’m not afraid of that,” she says. For inspiration beyond the art world Ball looks to album covers and posters, fashion, and filmmakers such as Roy Andersson.

Before we say goodbye, I ask Ball what she hopes to achieve with her portraits. “I don’t have any strong thoughts about how I want people to read them,” she replies. “It’s a purely personal thing for me. It’s all about my process.” Once she’s put down her brushes, she hands over the paintings for us to interpret in whatever way we wish. And therein lies their charm.

Ball is drawn to subjects who shake things up, and her enigmatic portraits encourage us to do the same. “I’m interested in anyone with a strong sense of self,” she says. A sense of self, a point of view, an opinion.

Chloë Ashby is an author and arts journalist. Her first novel, Wet Paint, will be published by Trapeze in April 2022

Images © Sarah Ball. Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery