The other day I was looking through old family photographs. Among the jumbled boxes of dog-eared digital prints were very embarrassing photographs me and a friend had taken when we were about twelve, our pre-pubescent fashion choices as awkward as our changing bodies. We’d dressed up for the camera and posed around my back garden, using the self-timer to capture ourselves imperfectly. I can remember clearly that we were trying to emulate a magazine shoot.

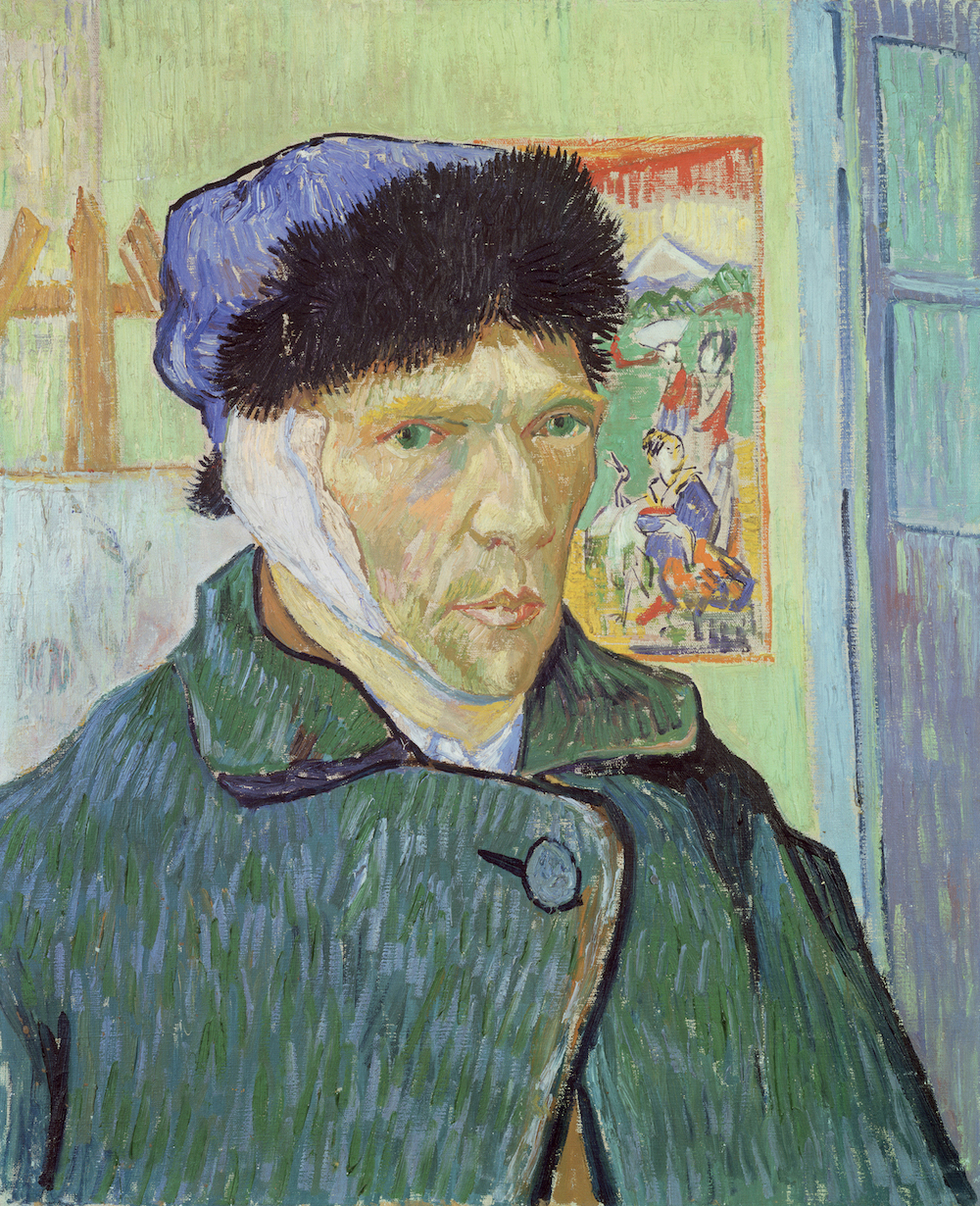

Robert Cornelius was the first person to take a photographic selfie, in 1839, but of course, before then the self-portrait was around for as long as we have been: we’re obsessed, it would seem, with seeing ourselves from the outside—something we can never really do.

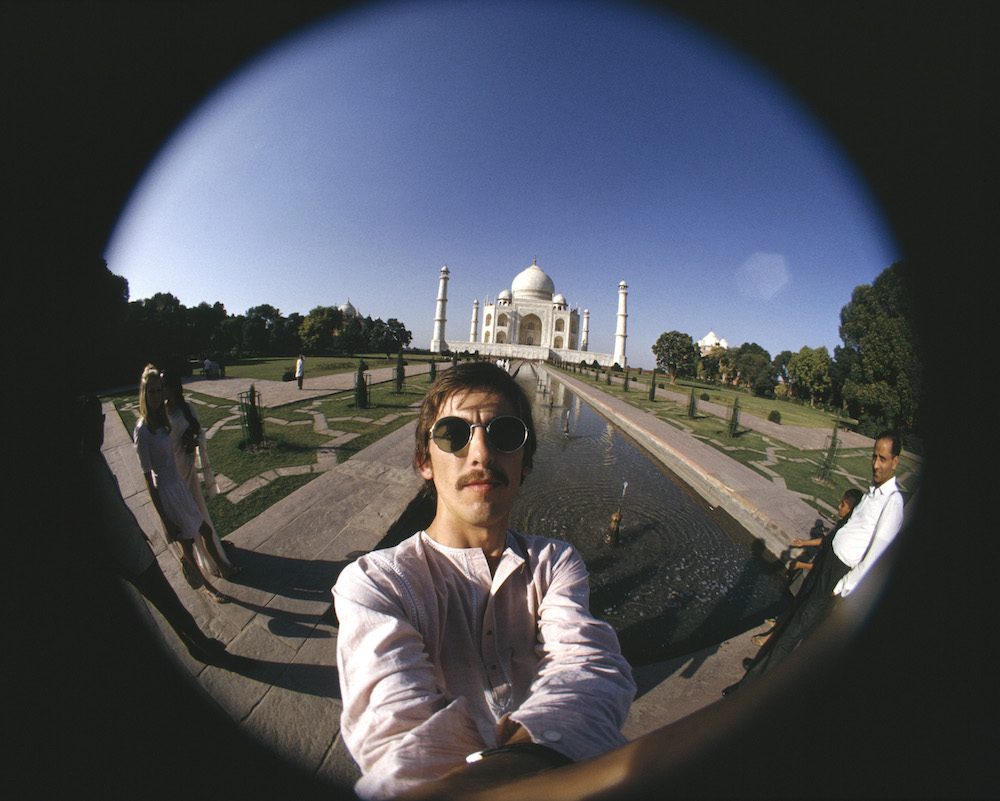

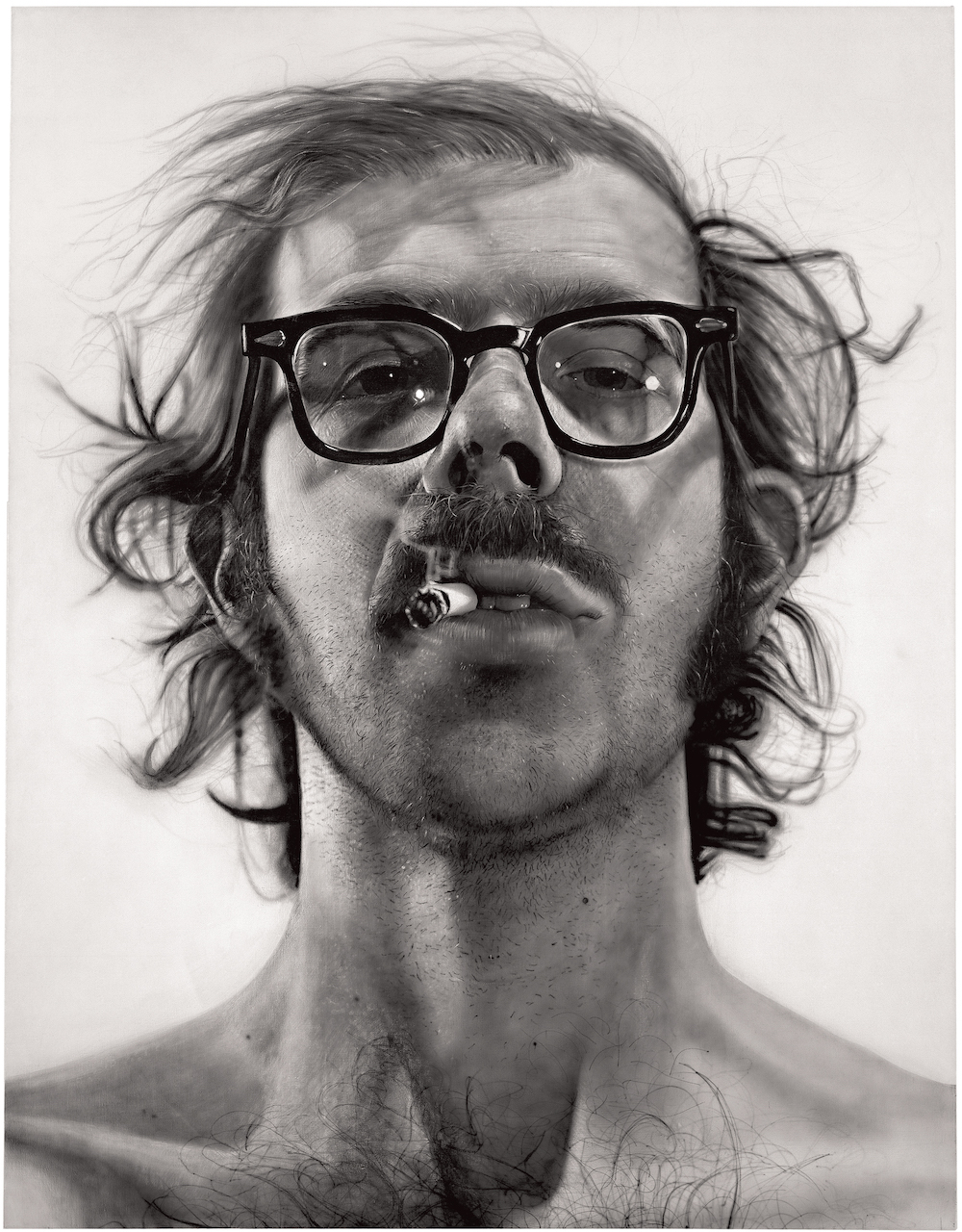

At the Saatchi Gallery, a somewhat gimmick-ridden exhibition, declaiming itself as the first exploration of the history of the selfie, attempts to trace the trajectory from painted self-portraits to selfies, from Frida Kahlo to “selfish” Kim Kardashian, from Egon Schiele to Barack Obama.

The selfie isn’t really a profound reflection on the self. The term—which is attributed to Nathan Hope, who commented on an Australian blog in 2002 using the word (he humbly says it was common parlance at the time, and he didn’t invent it) really refers to the specific phenomenon we all know and loathe: pointing the camera at yourself, with little purpose other than to look at ourselves. What they do share with the paintings and photographs of artists is that they are made to also be looked at by others.

Many of the works in this exhibition are not really part of this genre, and rather than elevating the status of selfies—which ultimately isn’t very convincing—perhaps it would be more interesting to look only at the selfies that were not intended as works of art, but that touch on the ways we look at ourselves through selfies. The media’s obsession with selfies seems only to be a reflection of how self-obsessed we are—we even have to unpick our self-obsessiveness.

Selfies can be artistic, expressive, even political (see the feminist selfie that emerged in 2013) and there are some examples of this in the exhibition, but all art is, when you boil it down, a form of self-expression, so this show may as well have included any artwork ever made. If the selfie really is art, why does it need examples from the past to make it stand up?

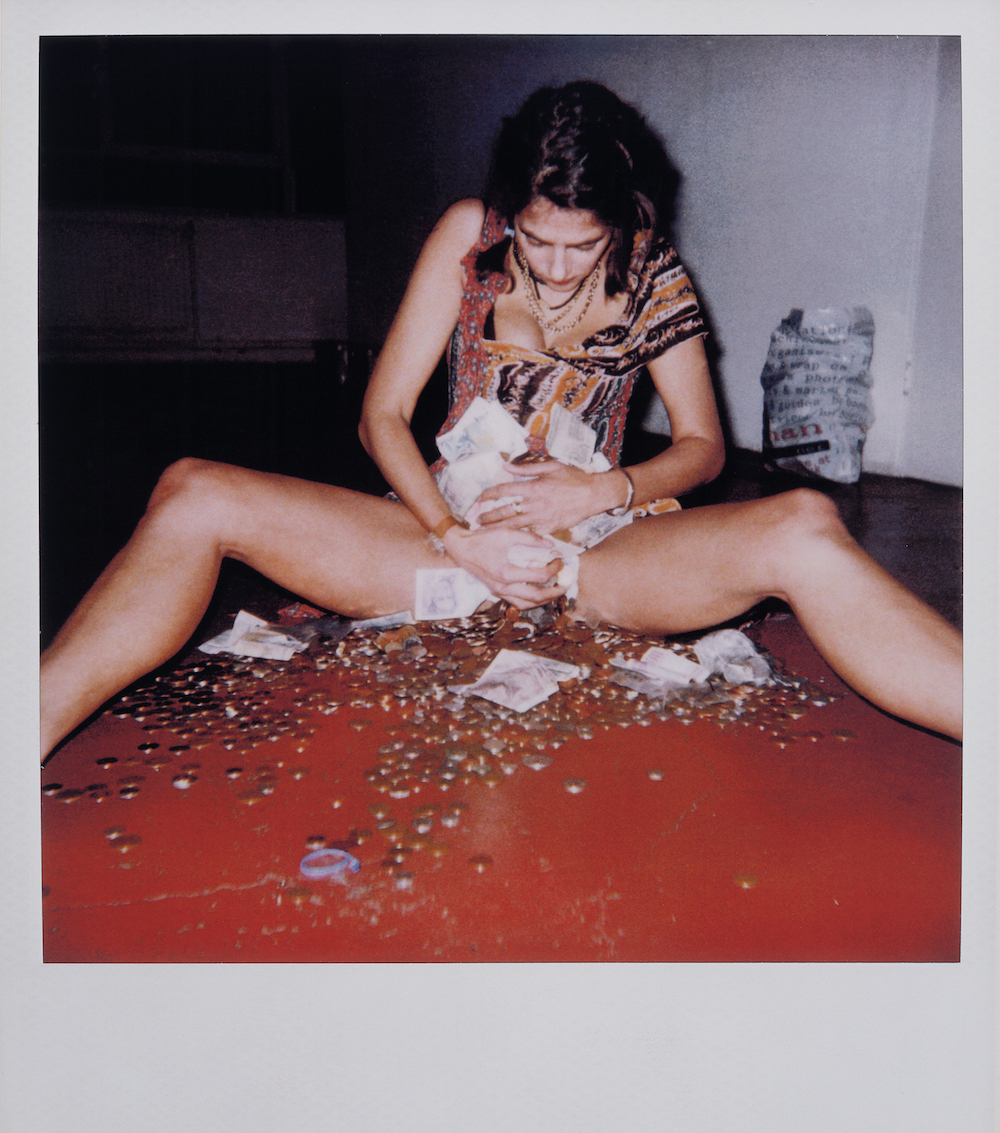

What’s really interesting about selfies is the psychological, sociological and physical problems they pose: that they now invade our lives everywhere we go, the way they can ruin our experiences of places and events. They be extreme, dangerous, and disturbing: think of the guy who took a selfie with what he thought was a terrorist about to blow him up; the Holocaust memorial selfies; Angela Nikolau, the girl who risks her life climbing to the highest places in the world to take a selfie shot—or the teenager who shot his friend and took a selfie next to his dead body. Selfies ain’t all fun. The troubling side of this trend is pretty much ignored in this exhibition, apart from one self-portrait photograph by Nan Goldin, her very famous record of domestic violence, a month after her boyfriend has battered her.

Going back over my own early “selfies”, created out of boredom and never intended to be seen, all I can conclude is that the impulse to capture our own image is natural. We’re simply trying to elevate our existence or alleviate our ennui, in the same way that the Saatchi exhibition is trying to elevate selfies. In Camera Lucida, Barthes predicts this: “Photography, in order to surprise, photographs the notable; but soon, by a familiar reversal, it decrees notable whatever it photographs. The ‘anything whatever’ then becomes the sophisticated acme of value.” Selfies, surely, are the most ‘anything whatever’ thing I can think of in our culture now. I don’t think we need all that history to explain that.

‘From Selfie to Self-Expression’ shows at Saatchi Gallery in London until 30 May. saatchigallery.com