It’s peak summer in New York when I visit Ugo Rondinone at his studio, the renovated former church in Harlem where he lives and works. Outside flowers are wilting in the heat, but inside under the arched doorways all is cool and quiet. A small pane of stained glass casts its colours on the foyer, and here’s an arrangement of pastry, peaches and strawberries on the table, all too pretty to eat. In what was once the church’s main sanctuary, blue painter’s tape marks out the floorplan of Gladstone Gallery in New York, where Rondinone is preparing for a show. This single room could accommodate the entire gallery, easily.

Rondinone is an energetic man in his early 50s, with an expressive face, close-cropped hair and a salt-and-pepper beard. He’s best known for his rainbow arcs of text (Hell, Yes!, Everyone Gets Lighter, Dog Days Are Over), bronze casts of monstrous heads, paintings of hazy bull’s-eyes, installations full of dozing clowns and, most recently, Seven Magic Mountains—the towers of DayGlo rocks currently residing in the Nevada desert. A retrospective of much of his recent work, Vocabulary of Solitude, which includes forty-five clowns, each paused in the middle of a quotidian activity, will travel next to CAC Cincinnati and the Berkeley Art Museum in summer 2017.

In the studio, Rondinone points to the orderly grid of his brick-wall installations (a trompe-l’oeil construction of wood, burlap and paint) and then to the tangle of threads hidden in the back. He sees the influence of both his parents in this work, his father the mason and his mother the seamstress. Order and chaos, natural and artificial, pop and the sublime: these sorts of dualities spring immediately to mind while I talk to Rondinone, who takes great pleasure in the contradictory—a soft wall, a passive clown or an artificial stone.

Where did you grow up?

I was born in Brunnen, a very small town that was like a postcard picture of Switzerland—a lake and mountains with snow on the top. My family had to move from the south of Italy to Switzerland just to survive. Growing up, I was always between two worlds. There was the world of my parents, the rural Italian landscape where everything is dry and desert-like, the colours are earth and stone, and Switzerland, where everything is green and has this kind of exuberance.

Did you spend much of your childhood playing outdoors?

Yes, it was a natural thing. In 2013 I was finishing up Human Nature at the Rockefeller Center, where I placed raw stone in the middle of one of the most developed parts of the world, Midtown Manhattan. So when I was asked by the Nevada Museum and Art Production Fund to develop a work for the desert I wanted to do the opposite—go into nature with something artificial. They breathe, stones. Once you paint them, you suffocate them. That’s how you can control nature, by killing it.

“I always saw the clowns as modern-day shamans”

When did the clowns first appear in your work?

The clowns were first a drawing, then a video, then a sculpture. In 1996 I filmed elderly people dressed as clowns, women and men. They were all over seventy years old. I choose the age group so they felt rested. I made the first clown sculpture in 2000. It’s out of practicality that I changed the same object to another medium so I could give it a new configuration, combine it with another medium, like video. People judge those clowns as melancholics, but they’re just the way they are—being. There’s no value attached, they’re just passive. What do you associate with clowns? Entertainment. In a field of entertainment, like the arts, to be passive is a refusal.

Clowns are a pretty divisive subject. Some people associate them with happy memories while others fear them.

I hear that all the time, but I’ve never met anyone who is afraid. The clowns show my philosophy of being an artist. Not being engaged socially, but instead enclosing myself and inventing my own world.

In your exhibition a few years ago at the Rockbund Art Museum in Shanghai, you used live performers instead of sculptures. Did this work out the way you expected?

It’s hard to control humans. They have to go to the toilet, they get hungry, they feel uncomfortable. So that made me think: that’s too much to control. The performers were instructed not to interact, but because they’re actors, sometimes they did.

They didn’t stay passive, they wanted to entertain people instead?

Yes. When a child came in, of course they wanted to do something. What I’m doing now in Vocabulary of Solitude is that, of the forty-five clown sculptures, there are two real people. You won’t know which ones they are until they move. It makes it a bit creepy.

Oh gosh!

But this is a tension, a nice tension.

How do routines and rituals shape your work?

Routine helps me to organize my activities as an artist. A calendar, the hours of the day or the alphabet, this kind of rigid system gives me an order to organize the work—I do seven cloud paintings because of the seven days of the week. For me, a reason to stop is when I have an outside system that tells me to stop. The stone figures at the Rockefeller Center or Seven Magic Mountains could be a stage for a ritual to happen, or where one has happened before. I always saw the clowns as modern-day shamans. The first group of clown sculptures wore shaman-like clothing: burlap, felt and fur.

Are there aspects of your work that are more for you than your audience? Things that are secret or hidden?

The most important aspect of my work is the dialogue between myself and the work. A viewer just sees the immediate things, but the artist is in constant dialogue with his work. I have some paintings that are little sketches, just the ground and pencil. The back of each painting has a collage of newspaper photos from the day the painting was made. It’s a hidden work because I don’t document it. I was influenced by On Kawara, but, while he has a mute, almost cold recollection of his day, I fill it up with an emotion. (His paintings are emotional too, but in a broader sense, the date becomes a device.) While On Kawara’s dates become an open ground that people can fill up, instead I add suggestions with little sketches. It’s very complicated—but it isn’t.

The Icelandic artist Ragnar Kjartansson said: “I think all art is super-accessible. It’s like sitting down with poetry. You have to read it again and again, give it time, and then you’ll understand it.” Do you agree?

Poetry has an inner logic, a personal logic that isn’t universal. The same goes for art. Nobody starts thinking in front of a painting, you just let it happen. You have to feel, you don’t have to understand. Once you give yourself to feeling, then you expose yourself. That’s enough.

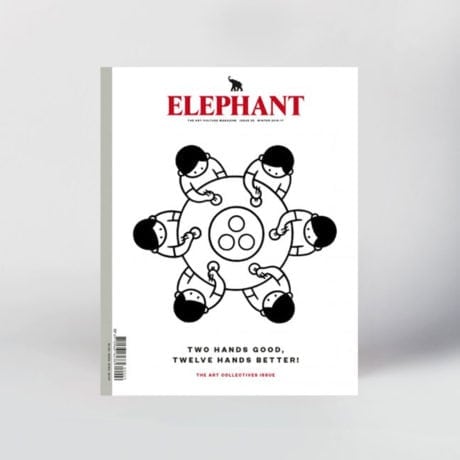

This feature originally appeared in issue 29

BUY ISSUE 29