Around 1466 Piero della Francesca finished a series of frescoes in the Basilica San Francesco, Arezzo, depicting the History of the True Cross. It’s a non-canonical story imagining that the wood used to make Christ’s cross was taken from a tree planted over Adam’s grave in Eden.

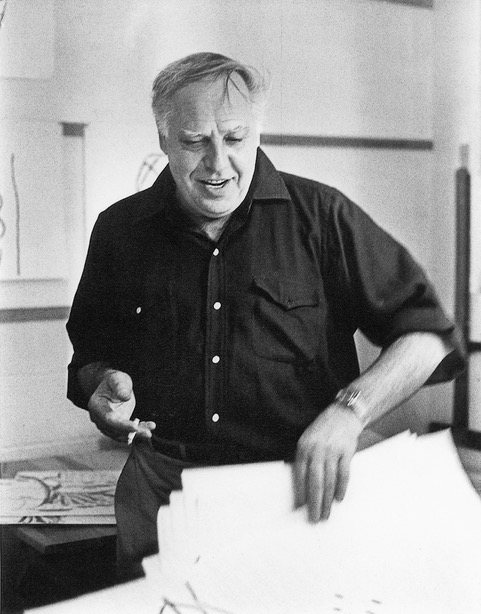

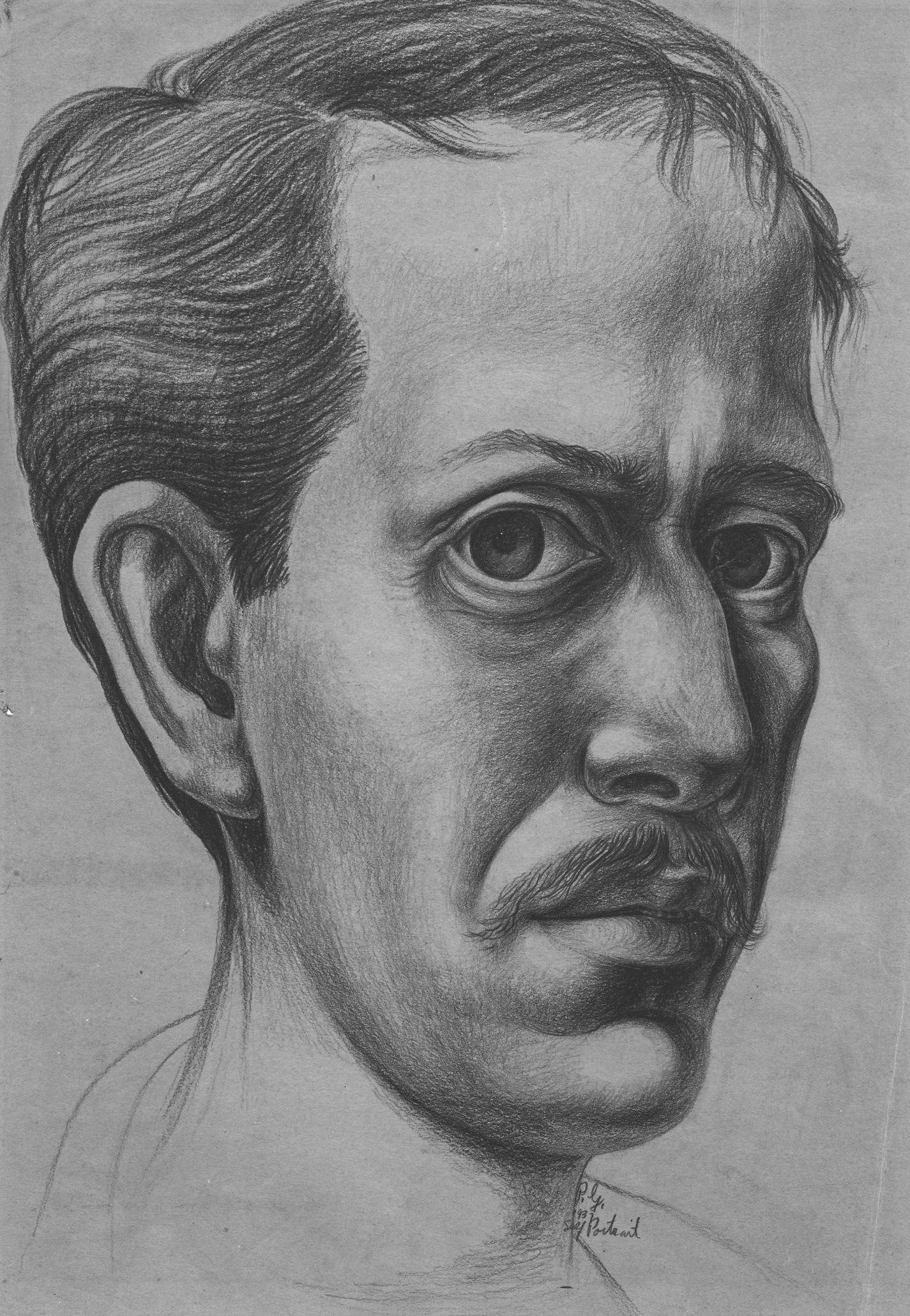

The frescoes at Arezzo are now accepted as Piero’s definitive work. They achieve a palpable sense of the individual-in-time that was revolutionary. Philip Guston first visited Arezzo in 1946. The frescos became a constant influence, guiding him through a career which saw many monumental changes in style. His rustic-yet-luminous palette is taken from Piero, as is his figures’ sense of being tangibly real and universally symbolic at the same time.

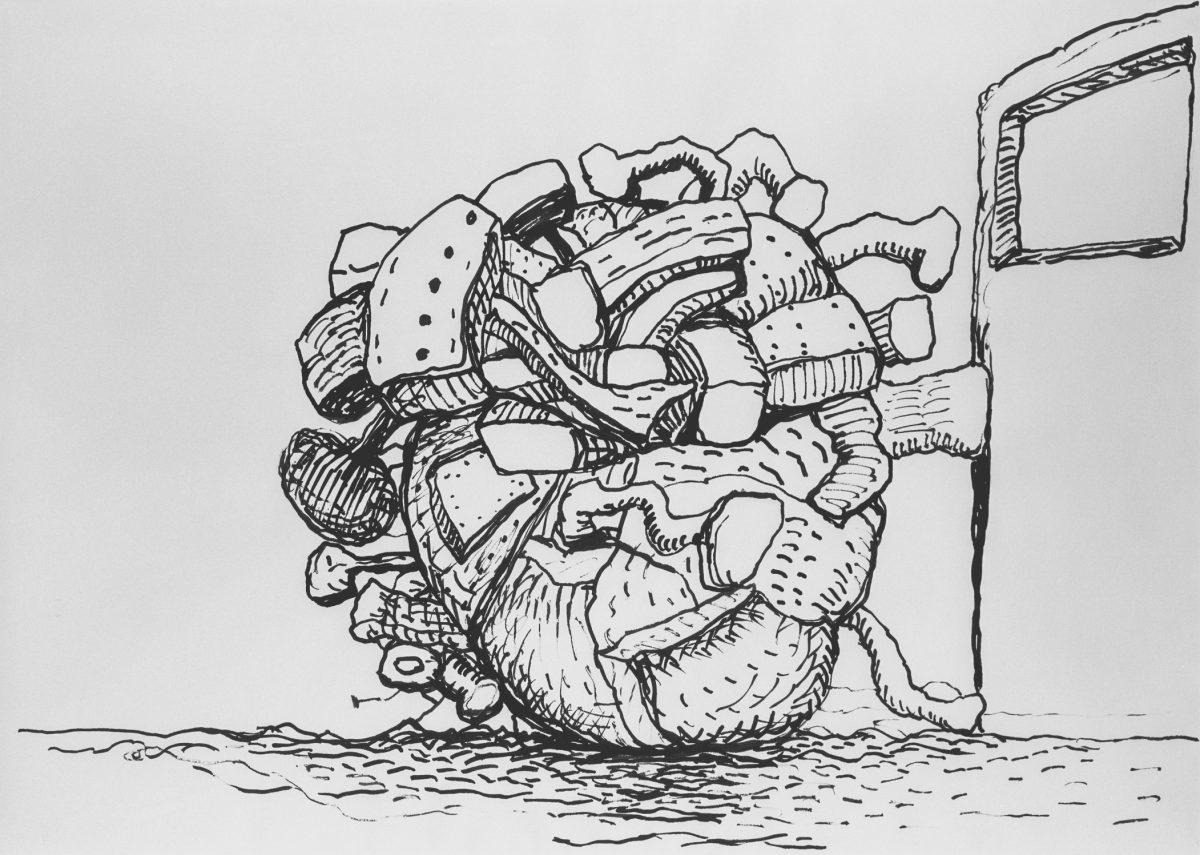

Giving a lecture at the New York Studio School in 1971, Guston pointed out “the figure that’s carrying the cross, there’s one testicle showing outside of his panty there”. The stubbly, bulbous, disembodied eyes which populate Guston’s 1970s paintings, even the testy jowls of the Nixon portraits, might have their genesis here.

The lecture appears in I Paint What I Want to See, a new selection of Guston’s writings. It includes lectures, transcripts of conversations, and some ‘studio notes’ (mostly culled from the 2011 Collected Writings, Lectures, and Conversations) covering the defining years of Guston’s career, 1960-1979.

“The best moments illuminate what’s important about Guston: his ever-present and effervescent faith in painting’s ability to tell fundamental truths”

Sifting through the conversational freeform for moments which may directly inform the paintings is part of the book’s fun, but it’s not always reliable. Guston’s fusing of eyes and testicles, for example, may have been more inspired by an experience which gets no mention. In 1933, Guston recalled that vandals “shot out the eyes and genitals” of his mural at the John Reed Club in LA. Curator Harry Cooper observes, though, in his catalogue essay for the upcoming Guston retrospective, that a photograph of the vandalised mural “shows no damage to the eyes or testicles”.

Guston invented or misremembered this detail, revealing his own ideas about what constitutes the important bits of the human form. Taken at face value, Guston’s own words provide less insight than the truth revealed by this inconsistency. I Paint What I Want to See

too often gives us the unaugmented musings of the man.

In that damaged mural, Guston painted the horrors of the Ku Klux Klan for perhaps the first time. Forty years later, in 1970, at the Marlborough Gallery in New York, Guston presented a series of hooded, cartoonish Klansmen smoking cigars, eating burgers, painting self-portraits. The show caused uproar that still reverberates today: in 2020, the Philip Guston Now retrospective was postponed over concerns about how these same paintings might be received. It’s finally due to be staged in Boston in May.

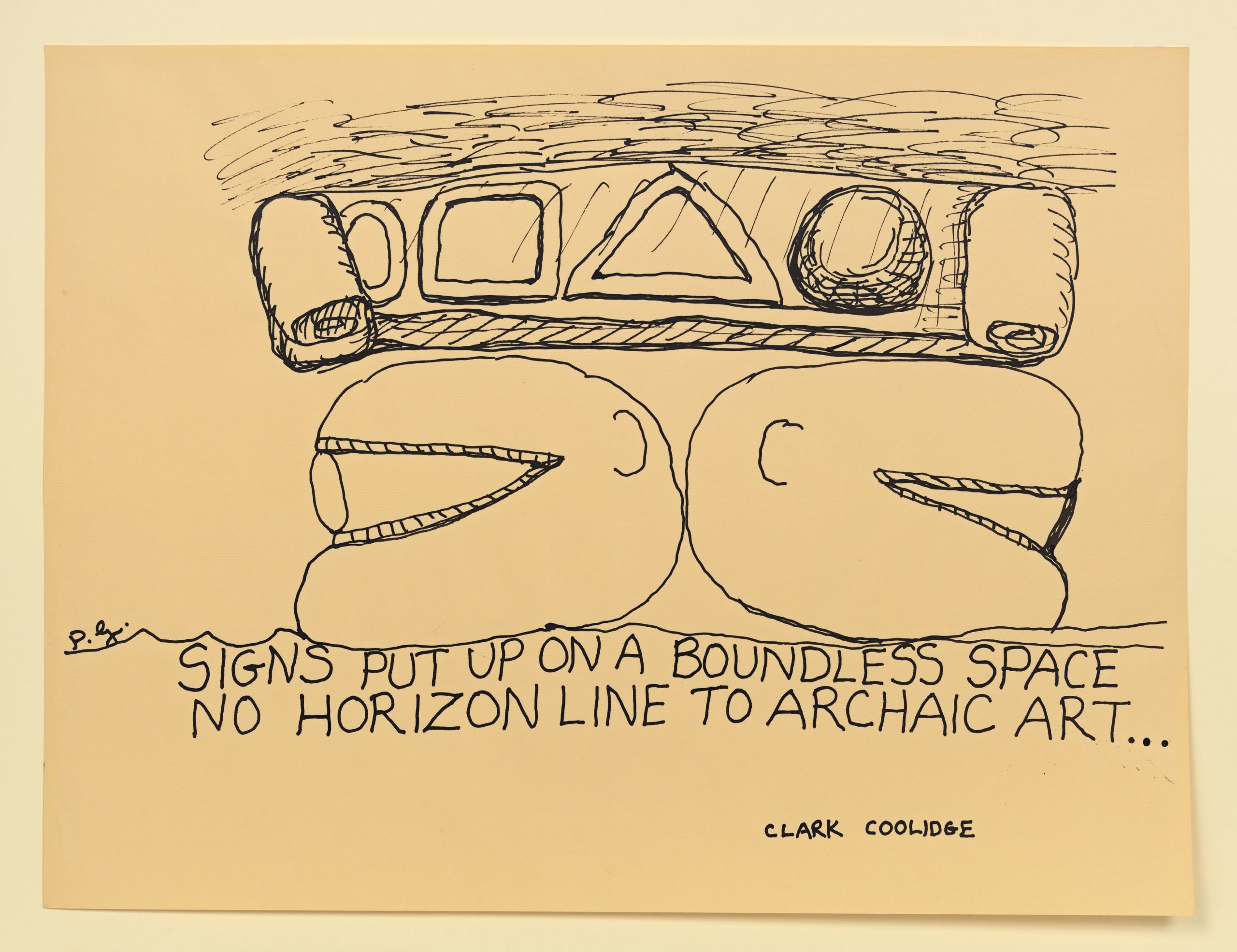

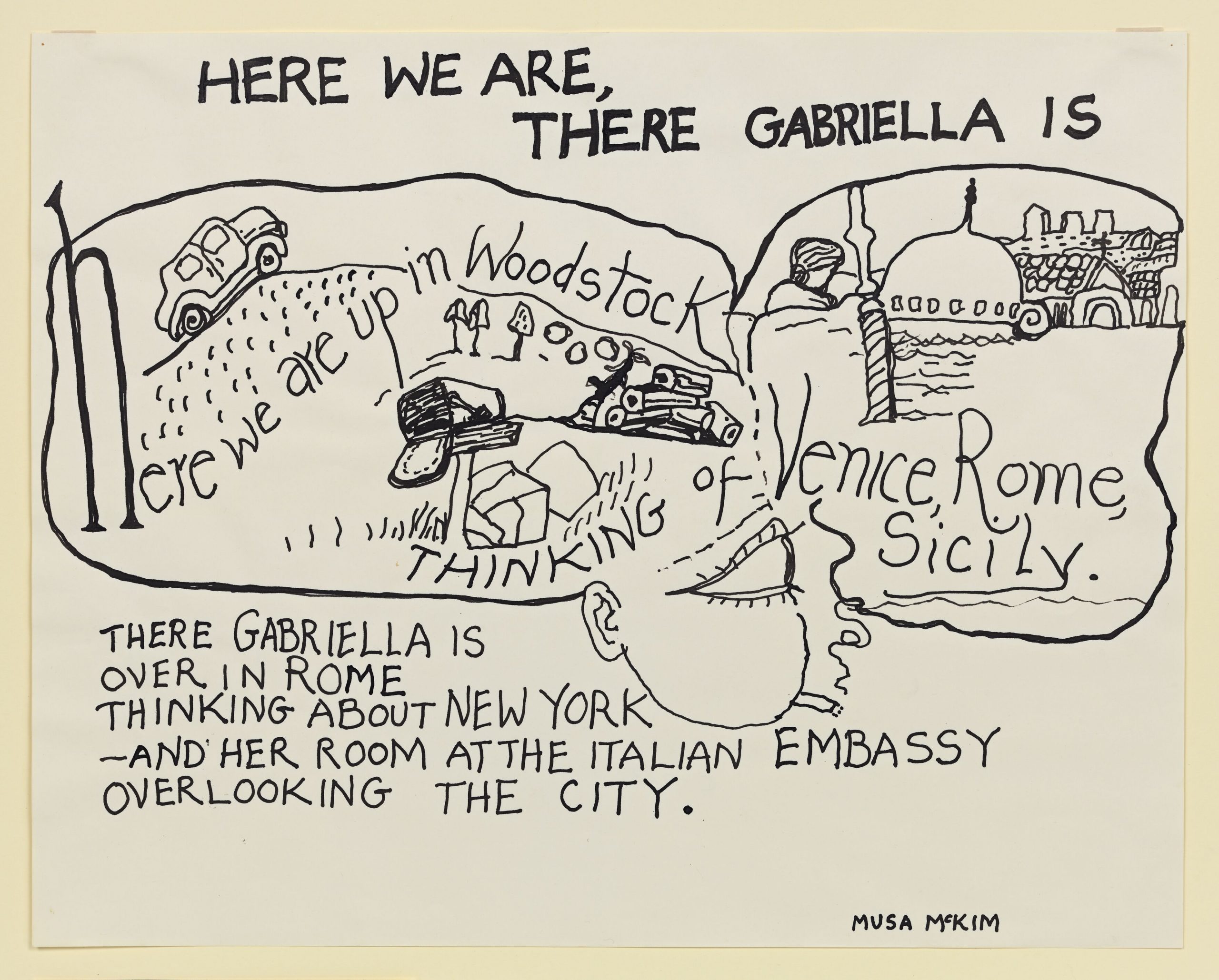

Also included is a meandering 1971 conversation between Guston and Clark Coolidge. The poet tells Guston an anecdote about Herman Melville which the painter writes down in his studio notes. The note itself is also included, meaning the story appears twice (clearly the editors are convinced of its importance). Guston writes: “Melville is writing to Hawthorne after having finished Moby Dick. He says, I’ve written an evil book, and I feel spotless as a lamb”.

Perhaps Guston, in the wake of his paintings of white supremacists, felt the need to assert his own spotlessness after creating an “evil work”. Of course, it was liberating for Guston to change styles, paint provocatively, then act impervious to criticism. But to insist upon this point would be to miss the power of his paintings and risk co-option by alt-right free-speechers. For the most part the collection avoids or at least complicates this impulse to make excuses for Guston, but, as in the repetition of the Melville anecdote, it doesn’t always succeed.

“Sifting through the conversational freeform for moments which may directly inform the paintings is part of the book’s fun, but it’s not always reliable”

Structurally, the collection is piecemeal and a little contextless. It cold-opens on Guston in the thick of an awkward interview with swashbuckling critic David Sylvester, then Dopplers away into a handful of scribbled journal entries and “poems” at the end. We get no introduction to Guston, no timeline, no commentary. But the best moments illuminate what’s important about Guston: his ever-present and effervescent faith in painting’s ability to tell fundamental truths, something he learns more from first-hand grappling with Piero and Giotto than he does from resisting criticism or asserting his right to offend.

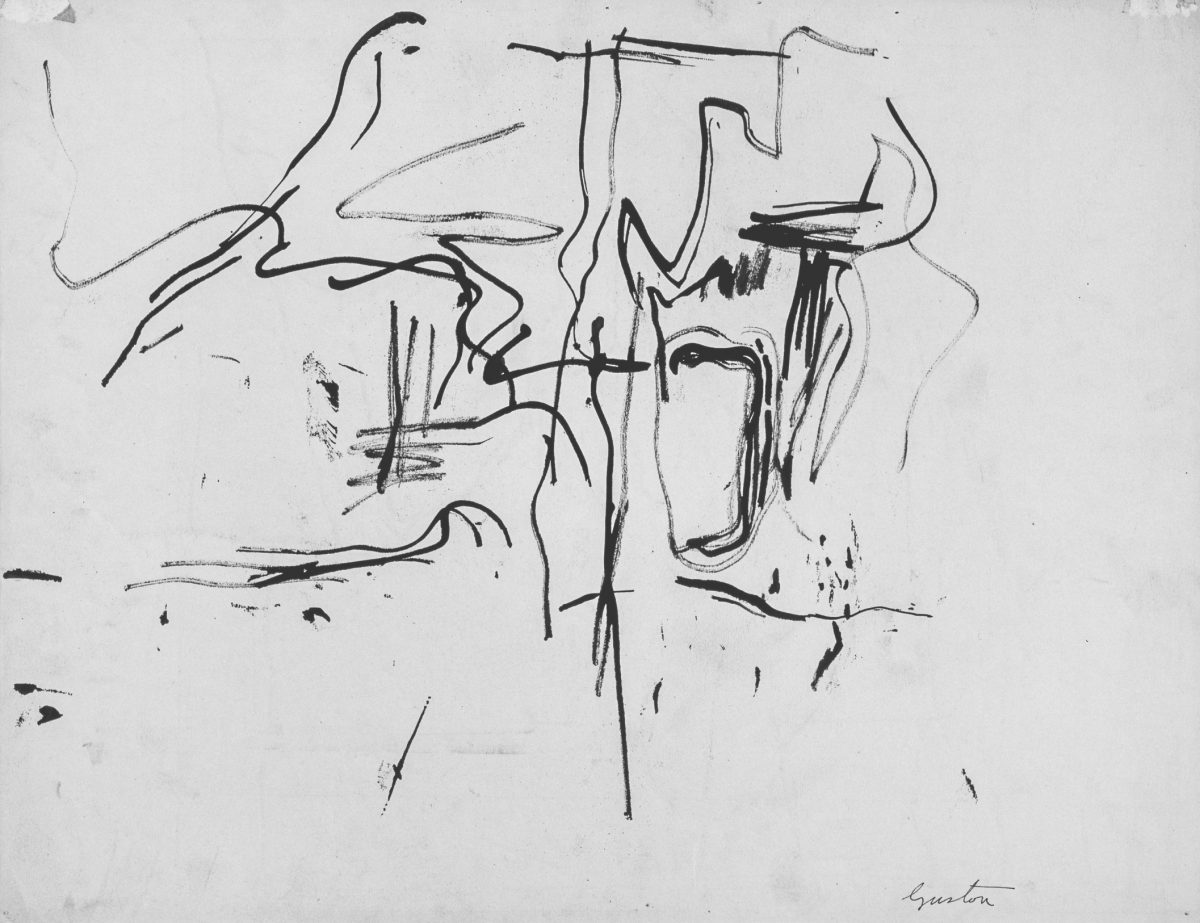

In the Studio School lecture, Guston zooms into the background of Piero’s frescoes, excitedly pointing out “the cluster of where the buildings are tightly packed in, and then the way the cluster releases itself and moves out so gradually”. Later, to Coolidge, Guston enthuses about how stationary objects “vibrate” when painted properly.

These observations shape the geometries of his 1950s abstracts. Paintings like Nature’s Return

(1957) and Voyage (1956) are full of forms releasing themselves, influencing each other, and resolving into something like a cityscape. Looking at ‘things’ in a dynamic way, revealing their inner motions, vibrations, and eventually the total flow of being alive, is what Guston is trying to catch in every picture.

“For the most part the collection avoids or at least complicates this impulse to make excuses for Guston, but it doesn’t always succeed”

Guston knows that the influence of shapes on adjacent shapes, the illusions of light and matter, are exactly the same in painting as in life, a cardinal truth that exposes something very real: the spark of Being which we all feel also exists in the sole of a hobnailed boot, a cigar, an abstracted cityscape, and, yes, terrifyingly, under the hood of a Klansman. We can learn more ethical ways of thinking if we allow art to teach us this fact.

Not only is Guston more than the artist who painted Klansmen, he’s more than this refutation. I Paint What I Want to See admirably strives for nuance ahead of a blockbuster exhibition preoccupied with affirming its own right to be staged. But Guston’s legacy can only begin to be appreciated once this question is out of the way and we can address his truest concern, which he expresses to Sylvester: “What is it, then, that you’re looking at?”

Adam Heardman is a poet and writer from Newcastle upon Tyne currently based in East London

I Paint What I Want To See by Philip Guston is published on 28 April 2022 (Penguin)