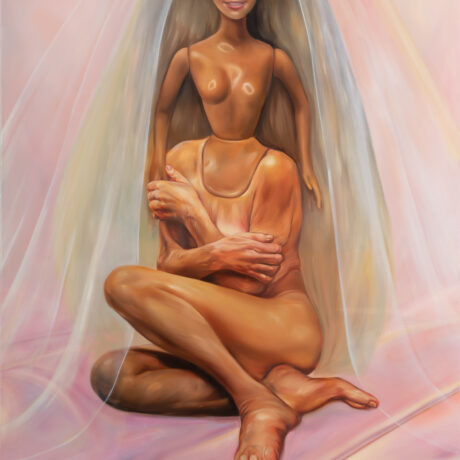

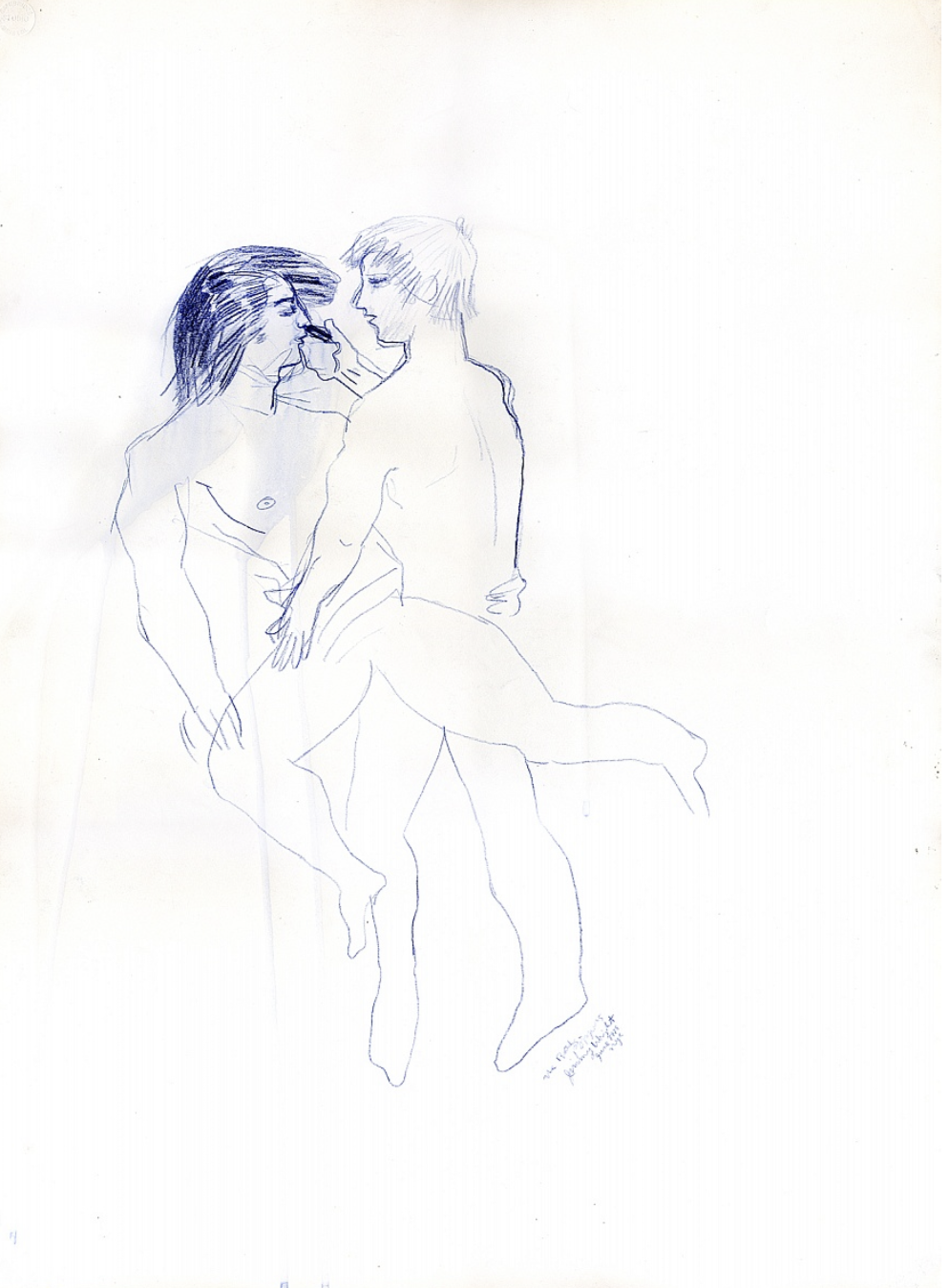

Inside Florence’s Uffizi Gallery, Sandro Botticelli’s ‘The Birth of Venus’ is balanced in-between abstemious surroundings, imperturbable to the individual observer as they pursue its fastidious brushstrokes, which have conceived her body’s curves, alongside its undulations, with their eyes, perhaps as thoroughly as they’d venerate over the inamorato that Michelangelo’s ‘David’has come to masquerade as. To put it flagrantly as Pablo Picasso’s proclamation that “Sex and art are the same thing”, nudity, whether unintentional on the artist’s part or not, finds its purpose in art galleries as much as the headsets, that stand waiting at its front doors, persuade us to inevitably, go seek it out. “When you look at a great work of erotic art, you sense a world outside its obvious parameters: a complicit triangulation between the creator, the subject (perhaps more than one) who inspired such intimate expression, and the viewer turned voyeur”, said journalist Rowan Pelling. “There’s a disruptive quality to the best erotica, which filters into your dreams and waking fantasies. It doesn’t seduce its audience—it transports them without permission.” However, the conundrum of whether our bodily carnality for certain pieces of artistic splendour can override our psychological appreciation for better or worse is a very tangible one and something which in retrospect, seems ever more plausible given my interaction with Michelangelo’s masterpiece was chorused by murmurings of domineering physical qualities. This is opposed to incredulous reflections over the knowledge that the 17-foot sculpture was forged from a solitary slab of white marble before Queen Victoria was gifted a nude replica, which she subsequently made more modest with a fig leaf. For some originators, including Quil Lemon’s whose ‘Quiladelphia’ showcase, hosted by the Hannah Traore Gallery, explored LGBTQIA+ and Black sexuality, along with vulnerability, the line straddling knowledge and nudity is a precarious as opposed to pleasurable one to walk. In a stark contradiction to scientists such as Julia F. Christensen, who’ve put forward the argument that, on the observer’s part at least, the dopamine rush they receive from their encounters with creative projects is separate from the pleasure induced by food and sex, sports, or drugs. So no, from her perspective and Healthline’s, you won’t have a spontaneous orgasm upon your foray into, say, Red Light Secrets: Museum of Prostitution in Amsterdam, which is recognised as the world’s foremost museum for its oldest profession, or Miami’s ‘World Erotic Art Museum, that, upon CNN Travel’s last count, plays host to a 4,000 strong presentation. Amongst them? A Karma Sutra-themed four-poster bed, a six-foot carved phallus and the occasional masterpiece by Rembrandt van Rijn and Pablo Picasso.

That being said, these are merely some of the dedicated spaces which delve into the ruminations of sex, and in Kat Toronto, whose work grapples with “concepts of sexuality, feminine beauty and gender roles” opinion, they’ve been a long time coming (no double-entendre intended). “Over the last ten years, I’ve definitely observed a significant growth in active engagement with LGBTQIA+ and heterosexual, sexual-orientated artistic works” she muses to Elephant. “I think this is being driven by a combination of both a desire for human beings to understand more of themselves and those around them, as well as the feeling that we can be more open about our sexual fantasies and preferences. Technology has also facilitated this in that it has helped broaden people’s horizons and expanded their understanding of diverse concepts and sexual possibilities, compared to two decades ago.”

“Whether deliberate or inadvertent, eroticism is invariably going to be magnified when placed in the context of a sex exhibition. We are bound by enduring connotations inexorably linking sexuality to eroticism. Is this a bad thing? I would say it’s not a negative at all, but rather it fosters potential new dialogues surrounding individual sexuality and how we engage with other human beings and the world around us.”

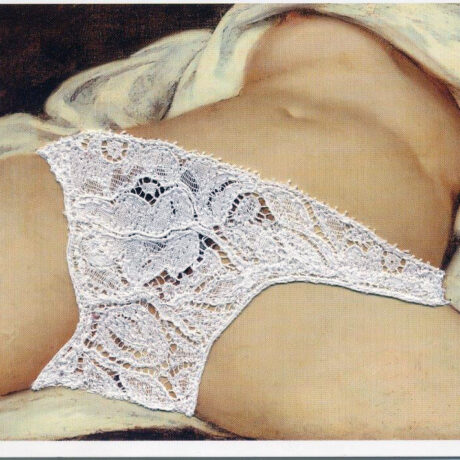

Jumping into bed with this position are various showcases which have, particularly, played out throughout 2023; the Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona played host to ‘Sade: Freedom or evil’ by presenting audiences with, as per its press release, “the impact that his controversial texts have had on a series of artists and intellectuals, and explains how he has become very present in mass-culture” “In the 20th century, numerous works referring to him directly or indirectly were created, which can be seen as a sign of the fascination, uneasiness, and contradictions that his ideas provoked last century” it continues. “As well as proof of the subversive potential of his literary production that still resonates today.” Simultaneously, the MOP Foundation, alongside Thaddeus Ropac, have independently encouraged visitors to feast their eyes on Helmut Newton’s’Big Nudes’ series, displayed amongst similarly prolific projects, Irving Penn’s ‘The Bath’project, which was realised in collaboration with the ‘Dancers’ Workshop of San Francisco’ focuses on 14 photographs captured of the company’s nude cohort in motion.

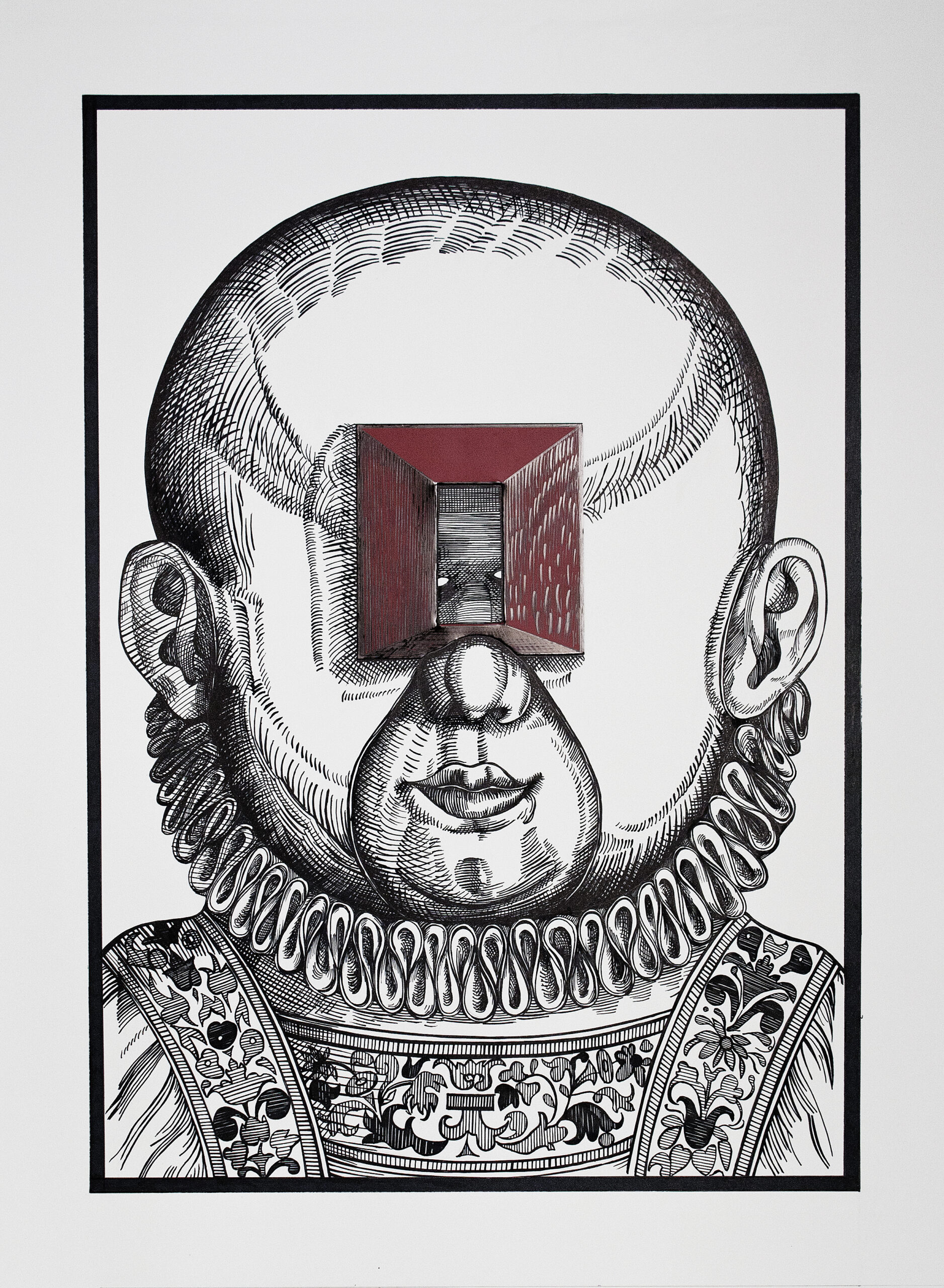

“Our current intellectual formation significantly influences, in my opinion, the way we perceive sexually-oriented artistic works. We operate with a pre-existing set of cultural indicators accumulated by our intellectual and visual history that begin to vocalise at the moment of engaging with the artwork” visual artist Ileana Pascalau voices. “For a concrete example: (whilst) what thrilled me at 13, (were) the illustrations in Sade’s novel ‘Justine’, (they) no longer evoke any erotic impulse in me today, when any form of torture of the female body repulses me.”

“Regarding works that address LGBTQIA+ experiences, I have observed another constellation of trends in the current artistic context I’m active in, namely the Berlin scene. Centuries of invisibility, fragmented expression and inhibitions have formed a prelude so painful that the successive “coming outs” of several decades have not exhausted the desire” she continues. “Or at least intellectually, we know we must continue to be aroused, both in mind and body.”

For spaces such as London’s Vagina Museum, in addition to its Museum of Sex Objects and New York’s Museum of Sex, this aspiration to stimulate visitors both cognitively as well as bodily is something to revel in. So much so that the latter in particular, is playing host to ‘RADICAL PERVERTS: Ecstasy and Activism in Queer Public Space, 1975-2000′, a heady showcase which navigates the tumultuous sexual culture alongside philanthropic endeavours of LGBTQIA+ public spaces from BDSM bars, bathhouses and porn theatres to parks and tea rooms. Inevitably, this uninhibited display is coupled with an aspiration to emphasise the aid these spaces gave their visitors throughout the HIV/AIDS crisis earmarked by the 1980s-90s through their encouragement of safer sex education, particularly because the virus was not being openly acknowledged on a governmental level. “Most of us respond to art with our bodies and emotions before we consider it intellectually. We are naturally drawn to what moves us, and erotic and sexually charged art can be quite affecting,” says Alexis Heller, the curator behind the showcase. “It can remind us of a previous feeling or encounter or yearning or spark questions about new desires or unknown histories. Any reaction that encourages a viewer to further examine what work is communicating is welcomed.” Nevertheless, it’s not all dildos and vibrators— particularly as preconceived conceptualisations people may have towards sex-focused spaces primarily steer towards objectification, as opposed to education. It’s in this vein that Museum of Sex Objects’ ‘Keeper’ Deborah Sim argues, “desires are formed from both our sensory and unconscious responses. In this way, the viewer would need to move away from their overwhelming visceral response to the sexually orientated artistic work to intellectually appreciate the piece.” To cut a very long story short, the biggest barrier that arises when it comes to our appreciating the educational facet these spaces can provide seems to be not what we’ve learned about sex, or the lack therefore beforehand, but more so the way in which we’ve been enlightened by others. Analytical research, for instance, has demonstrated that only 40% of young people in England (aged 16-17) believe sex education in schools is adequate. Simultaneously, an investigation into young people’s relationship with pornography by The Guardian found that “teenagers are learning more from pornography than sex education classes”, and it’s also many’s “introduction to sex.” That’s not to say that it’s impossible to break through this haze, so to speak, or that sex exhibitions don’t play an important role when it comes to doing so. “Many (people) come in assuming we are a brothel and have live sex shows. We sometimes see fear in the eyes of those who walk (through) the door…but they leave with a new sense of sexuality and its diversity. And that, yes, a sex museum can be titillating and classy at the same time,” Director of the Erotic Heritage Museum, Dr. Victoria Hartmann, says.

Words by Sabrina Roman