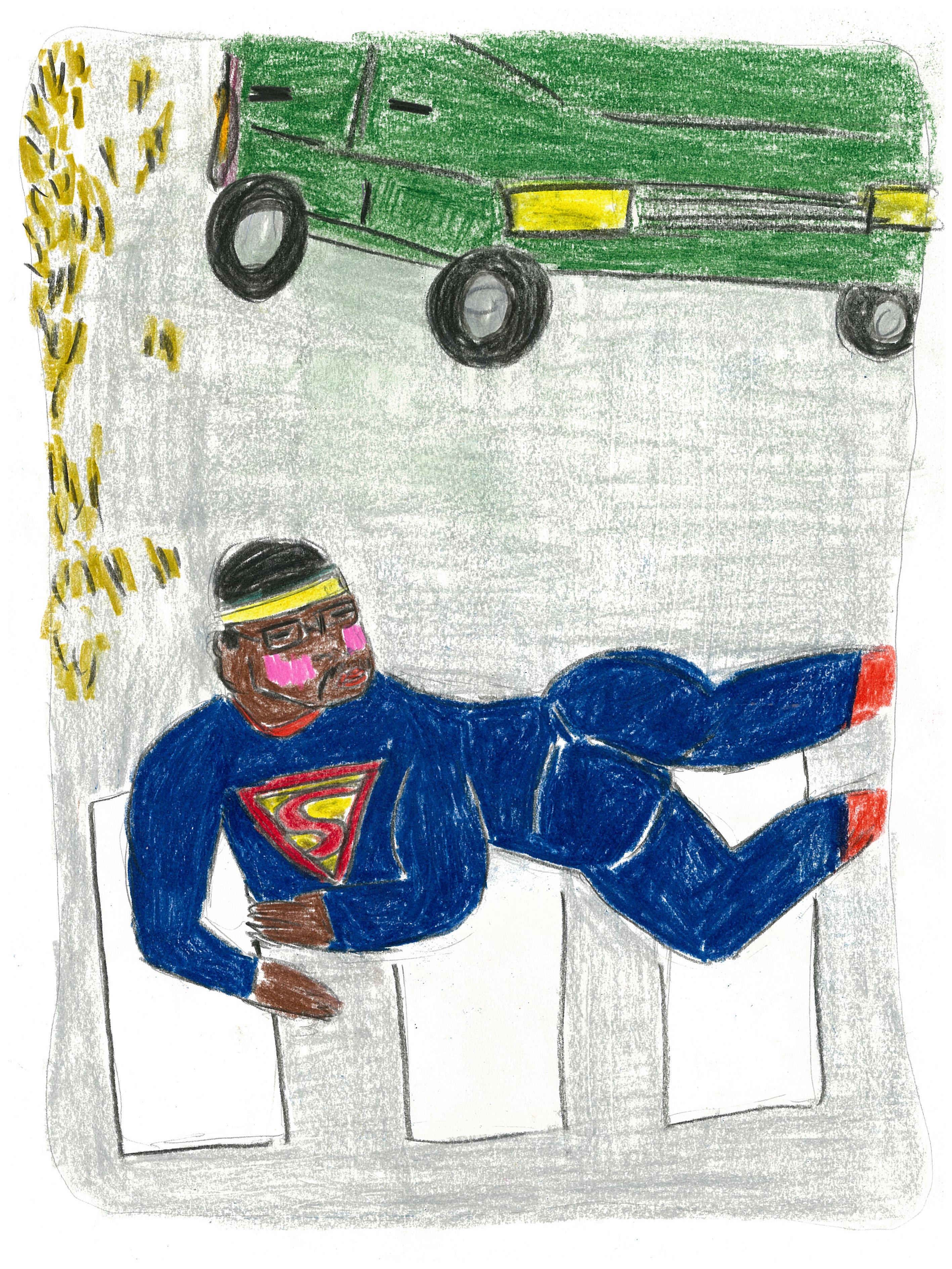

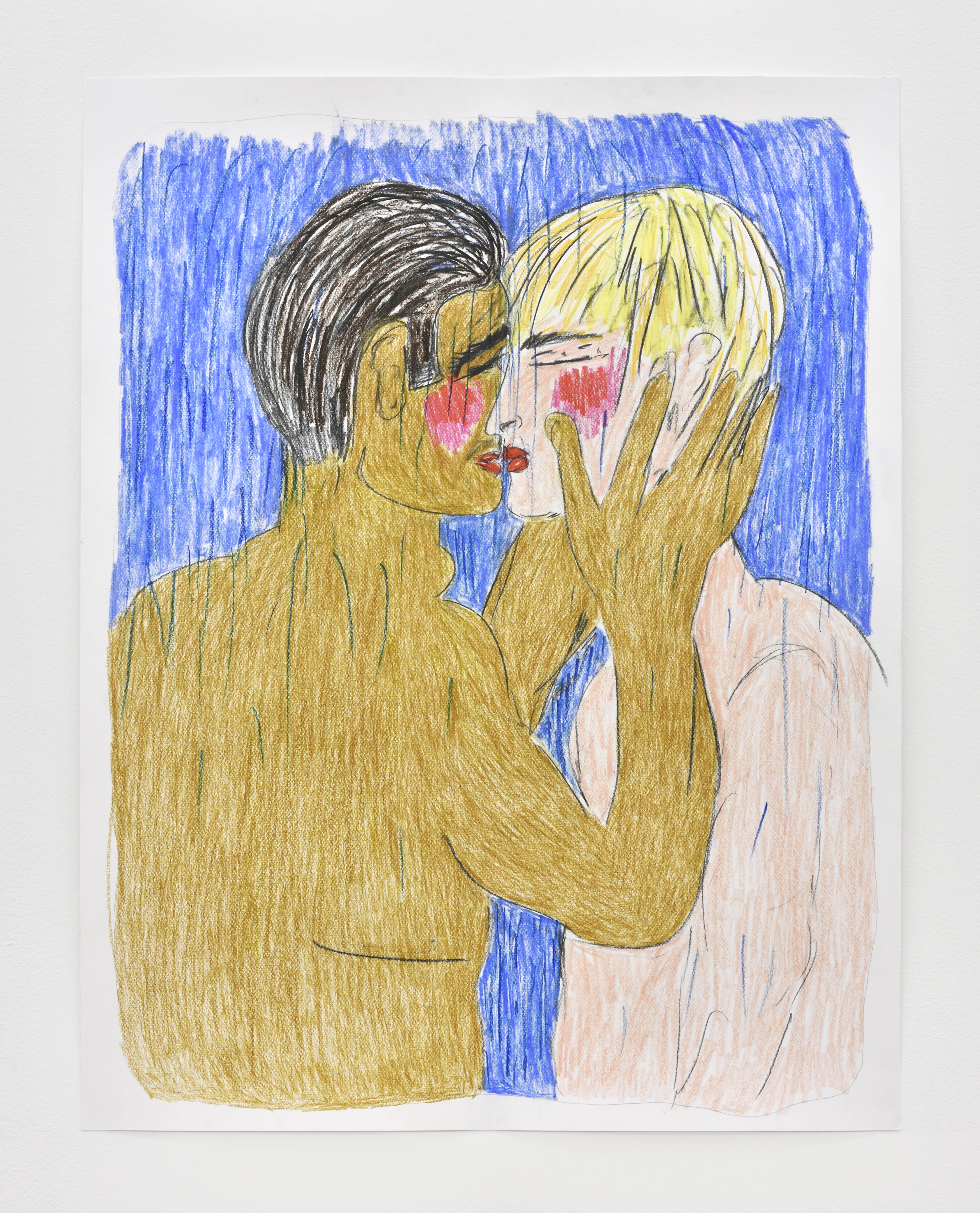

Soufiane Ababri is lying in bed. His recently completed Bedworks were made here—coloured pencil drawings sketched in a supine position—a way to physically change the perspective of his work, as well as a comment on the space in which it is created; domestic, private and intimate. The choice of simple, childlike materials add another layer of subversion to the series, toying with the idea of naivety.

As a gay African artist, Ababri’s explicitly erotic, wilfully subversive work is sympathetic to contemporary feminist ideas on gender and identity, and he is also concerned with colonialism and the exoticization of non-western male bodies. He takes traditional ideas about men—for example, by looking into the history of wrestling in Turkey, or by staging a naked football game in a cage—and confronts us with the dominant heteronormative and western way of seeing men in art.

Can you tell me more about the Turkish wrestling tradition you dealt with in your exhibition The Pill? How does that tie in with your interest more generally in sports and macho culture?

The first time I saw a Turkish wrestling match was on a gay porn website. In this video, you see two men coated with oil and grease and wearing only leather pants. They try to dominate each other by putting their hands inside the pants of the opponent. This proximity between male bodies touching each other, including the genitals, was sufficient to stoke the fantasies of Westerners and reconnect with homoerotic Orientalist imagery. I used this difference in interpretation and definition of virility as a starting point to try to understand the historical projection and legacy of violence generated by the Orientalist culture industry. Sport interests me, as a field in which it is possible to dissect the mechanisms of domination, and as a symbolic sphere from which to understand the role of violence in the history of forms.

You’ve been consistently interested in deconstructing the western and the heteronormative gaze in art history: how strongly did you feel those were things you had to

address in your own art, from your perspective?

I deeply believe that being part of a sexual and ethnic minority gives you a different view of the world. I believe even more that my work must be filled with “I” and allow me and my experience to assert that my view of art history, and history in general, is absolutely not like that of the majority. Then, for me, there’s also the question of urgency, to address issues related to visibility and the under-representation of sexual minorities and ethnic and disadvantaged class in the history of art. Heteronormative and white manhood have for a long time been the only points of view taken seriously in art. With my drawings and performance, I try to reverse this without reusing the forms of violence that have dominated me, and continue to do so.

You left Morocco to study in France, how much did that affect the work you were making, and how did it affect the way you saw yourself as an artist, confronting your identity and history from the outside?

I think it’s important to go away, to leave your home country. Flight is often necessary to find your voice. Morocco is a country where even as an anonymous individual I was denied the right to love who I wanted because of my homosexuality. It seems to me that this prohibition pushed me to be able to refuse and to question the domination and the control society. Refusing the authority of tradition allowed me to refuse the authority of the art school system, and to question everything, to rethink the very economy of my work and know what was paramount and even vital to me.

I think this way of getting involved as a social body in my work and pushing me to introduce performance as a kind of physical presence in my projects is a way to offload the weight of control. Even drawings can have repercussions… I seek to do away with relatives and to envisage solitude and insult by creating artistic forms.

Can you tell me about the role sex plays in your work?

We live in a time when pornography and sexuality are hyper-present in individuals’ lives. Yet, despite this, sex is always a problematic area that often involves difficult and dangerous repercussions if we decide to talk about it openly. Sex is one hundred percent political. It’s an area where the legacy of violence is very visible and reemerges in the form of fantasies—think of submission and rape as a kind of excitement or interracial relationships that use bestial and racist terminology—all this is part of a racial and postcolonial analysis and therefore it belongs to the political idea of a society of dominants and dominated. What I do plays on the ambiguity and complexity of these relationships.

What do you think makes a man?

I don’t know what a man is. I know that we are shaped by the social milieu from which we come, by cultural heritage and involuntary learning. It is always a question of deconstructing this heritage to be able to invent oneself. So maybe “man” as a traditional notion is a model imposed by the group. So a man, as I would like to understand it, is the product of emancipation and flight. A man who is ideal for me is able to completely invent himself and can enjoy playing with the ambiguities he creates.