For filmmaker Petra Bauer, film is both her medium and a powerful political tool. The Swedish artist’s work is always created in collaboration with a feminist-focused organisation, and uses film as a means to explore and present often complex, divisive debates within feminist discourse and contemporary society more widely.

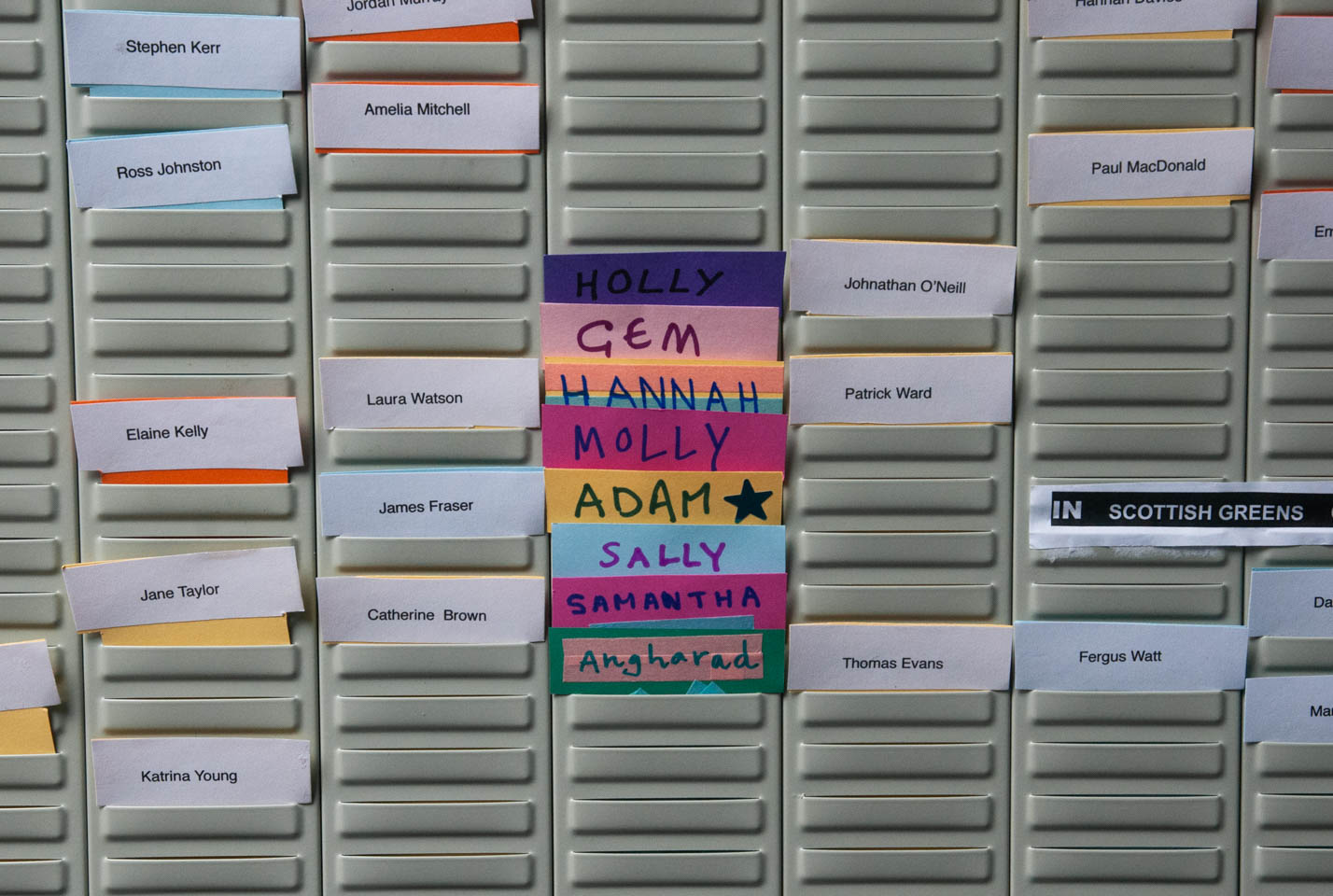

Her most recent project, Workers!, has just gone on show at Collective in Edinburgh, and is the result of a collaboration with SCOT-PEP, a sex worker-led charity that “advocates for the safety, rights and health of everyone who sells sex in Scotland”. The exhibition comprises a film, a workers banner created by SCOT-PEP and artist Fiona Jardine, audio pieces and texts about the sex worker rights movement. “I don’t think film is necessarily better than any other medium to discuss these things, it’s just the way I work—this is my tool, this is what I know,” says Bauer. “What I personally like with it is that instead of just using words, one can also use images—not everything has to be articulated through human language.”

We spoke to Bauer about the links between sex work and the traditional woman’s place in the home, and the fight for sex work to be recognized as a valid, legal form of labour—and as such, why its workers should be afforded the same justices as any others.

How did you come to work with SCOT-PEP?

For many years I’ve been interested in, or addressing and working with, feminist organisations both historically and in contemporary times. I always collaborate with an existing organisation of some kind, and what I’m interested in is both the struggles women have in today’s global society and what we can learn from each other’s conditions.

When I was invited to Edinburgh in 2015 for a period of research, I was interested to meet a number of different organisations and see how they organise, and what they address. Before I met SCOT-PEP I did not know much about sex workers’ struggles; I was very ignorant. I was intrigued by how they addressed the topic and and see themselves as part of a larger feminist movement, as well as part of a fight for the justice of migrants.

“If people had actually opportunities, proper benefits, decent wages and better housing conditions, then there’s a chance to see people doing sex work as an actual choice”

Were there any other artists or works you looked to in making the film, who addressed similar themes?

The Belgian filmmaker Chantal Akerman has been incredibly important to me throughout my career. In 1975 she made the film Jeanne Dielman, 23, Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, which follows a housewife for three days—she cooks, cleans the house, runs errands, tends to her teenage son. She’s a widow and also sells sex, so every day a client comes. On the last day, she kills the client. That film is interesting in terms of the feminist discussion about what women’s labour is; it’s also interesting for the aesthetics as it’s almost shot in realtime—there’s a lot of discussion about the way she used the camera as a proposal for feminist aesthetics.

In 2015 I decided to revisit the film and see if it would be possible to rethink it. The film is amazing, but the Jeanne Dielman figure is white, middle class, in Brussels—I wanted to question where we might find her today. Broadly, the three themes in the Jeanne Dielman film are woman as sex worker, homemaker and mother. What are these now? How can we think about these figures in a contemporary global setting?

You’ve said “the conditions for sex workers are intrinsically connected to larger societal structures”. Please can you elaborate on that?

The way sex work functions is visible in other forms of precarious labour, like Uber drivers for instance, and it’s an indication of how society is organised at the moment and how labour functions as a society. Another important thing is that a lot of men, women and trans people who do sex work are undocumented migrants, so the problem isn’t the sex work—the problem is immigration and the border. If those people were allowed to cross borders and work legally in the UK or elsewhere in Europe, there would be fewer migrants doing sex work—it’s the only job apart from domestic work that they can do undocumented to survive.

There are other people doing sex work who are students who can’t afford to study; and people in low paid jobs who simple can’t live off those wages. You cannot abstract sex work from other conditions in society. If people had opportunities, proper benefits, decent wages and better housing conditions, then there could be a chance to see people doing sex work as an actual choice. Sex work has always been addressed in feminist discussions around how a feminist woman can address it, both in the sense of unpaid sex work at home, and in the paid, commercial sense. Sex work is a feminist form of labour, and it can relate to domestic labour because it doesn’t actually produce anything.

What does the word feminism mean to you?

For me, it’s not a word; it’s a practice and a theory and a tool to analyse and engage with the world. But it’s important to remember there are many feminisms: I personally don’t agree with feminists who have a very liberal form of feminism, as in women want equal rights with men, the same wage and the same conditions. I’m fine with that, of course, but for me that’s not enough—for me it’s so important to change structures. For instance, some might say it’s not enough to have the right to vote, and that structures have to change; we still live in a patriarchal, capitalist society. At the moment there’s a critique of white feminism from black feminists who argue that gender analysis is based on a white, middle class perspective, which I can tend to agree with. That’s what’s happening at the moment, and to some extent it’s an interesting discussion about trying to articulate how it could develop.

“For me, feminism’s not a word; it’s a practice and a theory and a tool to analyse and engage with the world”

What do you think was the most striking thing you learned from working on the project?

SCOT-PEP wants sex work to be acknowledged as any other work; that would be a way of avoiding criminalisation because sex workers could fight for their rights and improve conditions. In the UK it’s not illegal to sell or buy sex, but everything around it is illegal—you can’t solicit, support a partner with the money earned from sex work or support adult children for instance. It’s that criminalised environment which makes it super difficult to navigate in relation to society. If sex work is decriminalised, it gives the power and agency to sex workers themselves—that’s the most crucial thing to me as an artist and on a personal level. What’s crucial is that we listen to sex workers about what they need to improve their conditions. This is something the feminist movement have missed: the biggest lesson I have learned is the importance of actual listening to sex workers, not victimizing them, giving them space and agency and seeing sex work in relation to other forms of labour.

Petra Bauer and SCOT-PEP, Workers! runs from 13 April -20 June 2019 at Collective, Edinburgh