“I really bare it all. I don’t believe in hiding anything,” artist Tonia Nneji says of her work. She is partly referring to the semi-clad subjects in her paintings, but also to the way she has deals openly with her experiences of chronic illness. Alongside posting pictures of her paintings, Nneji often candidly discusses her health issues on Instagram, from the symptoms of her polycystic ovary syndrome (a medical condition that causes an imbalance of reproductive hormones among women, as well as insomnia, weight gain and depression) to the effective solutions she has found over the years. For Nneji, artistic work and illness are inextricably linked: she sets out to represent and reach out to a community of women forced to be silent about their trauma and pain, hoping to break what she has called out as a culture of suppression and shame for women.

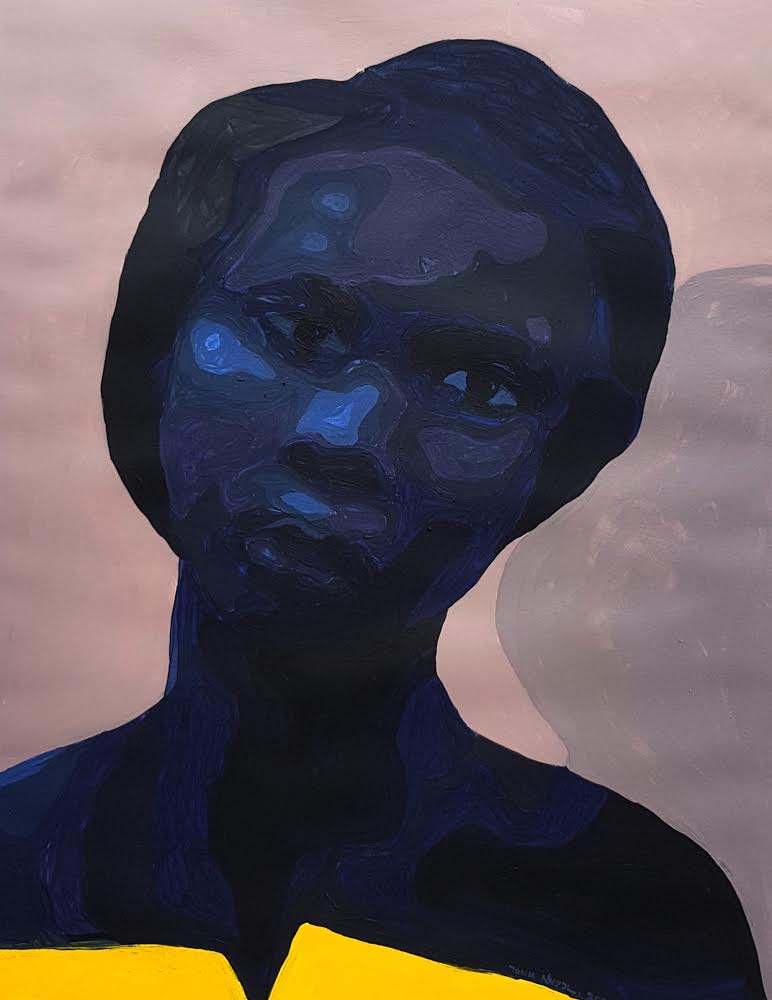

After her diagnosis, Nneji believed she might never lead a ‘normal life’ as a woman. However the community she found online brought her hope, and some of her paintings in turn seek to pay tribute to that community. In Portrait of a Cyster, a self-portrait that sees the artist’s solitary figure in sombre blue hues posed atop a swathe of brightly coloured fabrics, she communicates her own suffering and the support she has found through sisterhood and sharing.

“The images I paint are planned and exact. None of it is imagined or accidental”

In her 2020 exhibition You May Enter at Rele Gallery in Lagos, Nneji presented paintings in her signature blue acrylic, with trademark featureless figures, exploring another way in which she has sought help. While her figures’ expressions are blank (an ambivalent gesture that makes these women both everywomen but also invisible, overlooked), Nneji projects a feeling of intimacy, using richly detailed, prismatic ankara fabrics to tell stories about her search for solace.

Motifs on these textiles signal the names of local churches and other religious houses that Nneji visited in Lagos in search of solace. They are places she was initially reluctant to go to “but there’s always someone who cares about you and wants to take you to some church, hoping it will help your pain—it’s an African kind of faith,” Nneji explains. In the double portrait, A Dust Memory (A Trip to See Pastor Matthew in Ago—Hausa, Ajegunle, Lagos) the fabrics that cover the figures reference Kwara Baptist Conference and Women’s Missionary Union, both places the artist has visited in search of alternative therapies and treatments.

Nneji’s use of ankara (the Dutch wax fabrics decorated with African motifs that form part of everyday life in Nigeria) has a particular personal resonance for the artist. “When I have my episodes, I am completely naked. It is my mother who covers me with fabric,” she explains. Ankara is intertwined with Nneji’s healing: her mother once had to sell her own collection of fabrics in order to cover medical bills. This is a sacrifice Nneji recognises specifically in her work, directly referencing the patterns and prints of these lost fabrics as a way to preserve them. “The images I paint are planned and exact,” she says. “None of it is imagined or accidental.”