During Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship (1973–90), Chilean women in shanty towns outside Santiago made colourful appliquéd textiles known as ‘arpilleras’. Embroidered with scraps of fabric left behind by missing or imprisoned friends and family, their patchwork imagery denounced political violence. Because of their folksy appearance, these pieces were initially overlooked by military authorities. By the time their subversive streak was detected, many had been exported, spreading crucial awareness of the regime-sanctioned crimes.

This is just one of the illuminating stories told by the UK-based textile artist Lynne Stein in Shedding the Shackles, a richly illustrated book that explores the empowerment of women through craft. Undeservedly dismissed as an inferior art form in the past, today craft is respected as a medium that excels in form as well as function. Artists such as Louise Bourgeois and Joana Vasconcelos have proven its conceptual potential, while the issue of sustainability has sparked a resurgence of interest in how things are made. Craft can be collaborative, restorative and impactful. As Stein shows, it can also be a means of survival and a powerful tool for change.

The book is divided in two parts, the first of which introduces the reader to groups preserving traditional practices. On Kihnu, an island one hour’s ferry ride from mainland Estonia, textiles play a specific role in society, with certain shades and fabric designs conveying a woman’s status. Elsewhere, there are individuals giving age-old skills a facelift: Celia Pym’s ‘socks’ series applies the art of repair to brightly logoed sportswear, while Lauren O’Farrell combines stitching and graffiti, resulting in quirky crocheted characters who inhabit public spaces.

“With each of her case studies, Stein spins a narrative that takes the reader from field to loom to market, shop or gallery”

The second chapter is a deep dive into a dozen women’s craft initiatives. With each enterprise, Stein gives a backstory, painting a vivid picture of the culture from which it was born. She begins in Bosnia, shortly after the outbreak of war in 1992. After visiting a refugee hostel in Galina, the Austrian painter Lucia Lienhard- Giesinger founded the Bosna Quilt Werkstatt to bring some colour back into the lives of displaced women.“The productive environment, and indeed the physical act of employing needle and thread, provided the refugees with an element of protection and stability,” writes Stein. It also provided them with a regular means of income, and continues to do so. Today the abstract quilts are displayed around the world.

Celia Pym, First One’s the Best, 2015

With each of her case studies, Stein spins a narrative that takes the reader from field to loom to market, shop or gallery. We learn about the dependence of indigenous crafts on local materials, from bamboo in Japan to sisal in Kenya, as well as the benefits of fostering relationships between indigenous artisans and designers. She describes the process for making beads, braids and baskets, while acknowledging the significance of funding and fresh ideas: thanks to new training programmes and production methods, Madhubani papier-mâché (a low-cost, eco-friendly craft in the Indian state of Bihar) has achieved both national and international status.

Threaded throughout the book are notes on history, geography and politics, as well as merchandising and marketing. Together, they point to the positive impact these craft projects have on poverty and gender inequality. Craft requires patience and attention to detail; it is a means of expression that can be practised alone or as part of a collective. The Thread Bearing Witness project sees artist Alice Kettle collaborate with refugee women and children in camps to make illustrative pictures, bags and banners. In Stein’s words, she is using stitch—“a common and universal language”—not only to address issues of migration and displacement, but also to “establish bonds and create resilience”. This resilience often ricochets through communities via skills and, perhaps most importantly, a shared goal.

Chloë Ashby is an author and arts journalist. Her first novel, Wet Paint, will be published by Trapeze in April 2022.

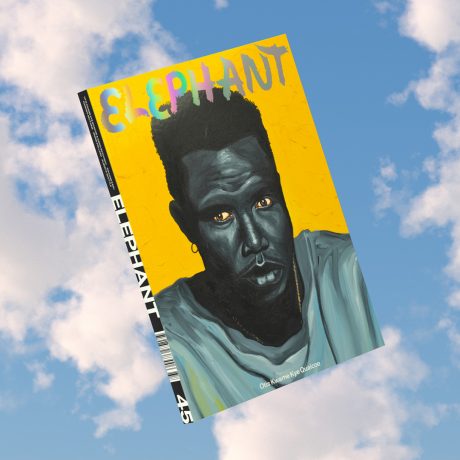

This article originally appeared in Elephant issue 45

BUY NOW