In her ongoing series ‘Ghostwriter’, the Iranian-American artist retraces her parents’ political exile in an homage to the lives they have built for themselves

The daughter of two Iranian pro-democracy activists and refugees who started over in the US, Sheida Soleimani (Indianapolis, Indiana, 1990) spent her childhood feeling like a fish out of water. “I didn’t fit into the cookie-cutter ideals of those that I grew up with,” she says, thinking back to her salad days in Cincinnati, Ohio. Having begun to speak English at a later stage than most of her peers, the multimedia artist recalls “always being the ‘weird’ one” among her group of friends. “I was raised in a very specific place in the States — a place that was not hospitable to people like myself and my family,” Soleimani explains. “A lot of the questions I would ask myself daily concerned whether I wanted to fit in with those around me or push back to develop my own identity: with the support of my parents, I was able to embrace the latter.” Having come to terms with “being a misfit” that clashed with the American Dream, she took it as an opportunity “to push the boundaries even further”, and she hasn’t stopped since: “My Bâbâ’s life motto is ‘comfort = death,’” Soleimani says. As a millennial, she is the first one to seek that stability at times, “but I don’t think I should ever allow myself to be too comfortable”, the artist adds. “Whatever mantles we take on, we should continue to challenge ourselves, leaving room for our identities to shift and evolve.”

With a BFA from the University of Cincinnati’s College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning and a Master of Fine Arts from Bloomfield Hills’ Cranbrook Academy of Art, today Soleimani’s practice spans art, teaching, activism and her work as a wildlife rehabber — a passion that was passed on to her by her mother. “When my Mâmân could not continue nursing after moving to the US, she became a wildlife rehabilitator,” she says. Care work had always sat at the core of Soleimani’s family, her father being a doctor. As a child, Soleimani observed how her mother looked after animals to grant them a new life. It was an experience that struck a chord in the artist, prompting her to embark on a similar path. Now a federally licensed wildlife rehabilitator, “I do the same kind of work in my own in-home rehabilitation centre”, Soleimani explains. Assisted by a vet, she provides medical care to a number of creatures — a side job that enables her to expand her horizons and continue to acquire new skills even outside of art, her main professional field. Still, Soleimani’s multifarious production, encompassing photography, film, performance, collage and sculpture, and her relationship to the animal sphere have always gone hand in hand.

“When I first started out as an artist, I used to integrate dead birds in still lifes,” she says. As unconventional as that might sound, choosing to stick to those images was a way for her to not be perceived as a threat by the Iranian government. It was only in 2010 that, upon being denied entry to her country of origin due to its growing political tensions, Soleimani realised that a shift of perspective was needed. At the time, she had just received a university grant to visit the remains of her mother’s home when the unexpected change of plans left her hopeless. “I was upset,” Soleimani recalls. “All I could think was, ‘Will I ever actually be able to visit [Iran]? Should I limit myself to non-political work to preserve my hope of doing so?’” Soon, the artist understood that it was her moral obligation to leverage the uncensored platform she had to address the Iranian political situation through her artworks. “I wanted my work to speak about my parents’ stories,” Soleimani explains. “Since 2011, my craft has become an exploration of Iran’s sociopolitical climate, its tangled political history and the roles and narratives embodied by my parents as both activists and caretakers.”

National Anthem (2015), her artistic breakthrough, saw the artist combine garish still life shots containing anything from fruit, animal fragments and decomposing flowers to objects echoing the Iranian tradition and archival close-ups of body parts, with widely provocative self-portraits of herself posing across various locations wearing nothing but a pink hijab. With each of the photographs part of the series hinting at a specific chapter of Iran’s history, the work was intended “to draw people in”, Soleimani told author and cultural critic Rosanna Mclaughlin in a 2017 interview. If at first, viewers are captivated by the striking tones and pop art-passing aesthetic of her visual assemblages, “when they realise what the content is, they are forced to spend time with it”, she explained on that occasion. It is a statement that holds true even in relation to her later bodies of work, including To Oblivion (2016) and Medium of Exchange (2017-2018), which, like most of her oeuvre, examine the power of imagery to shape the dominant understanding of global socio-politics and the relationship between the West and the Middle East.

Whether erecting sculptural memorials to the women who were unlawfully imprisoned, tortured and executed by the Iranian state or condemning the exploitation and violence legitimised by the oil trade between the US and the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), Soleimani’s art tells the stories that fall through the cracks of history — be it because of censorship or due to the biased narratives that dictate our view of the world. Among such lost mythologies stand out the lives of her parents, who fled Iran at the dawn of the 1980s as opposers of the Shah government and the totalitarian regime installed by the Ayatollahs following the Iranian Revolution (1978-1979). With Ghostwriter, her newest ongoing series, Soleimani, turns the lens inwards to recount their political exile through their joint perspectives. “I have been wanting to make this work my whole life,” she says. “I just didn’t have the right language or the maturity for it, but I now feel ready.” The project, which was recently acquired by the Victoria & Albert Museum to commemorate the one-year anniversary of the Women, Life, Freedom protests in Iran, applies the artist’s research-led, multilayered approach to a more openly personal storyline.

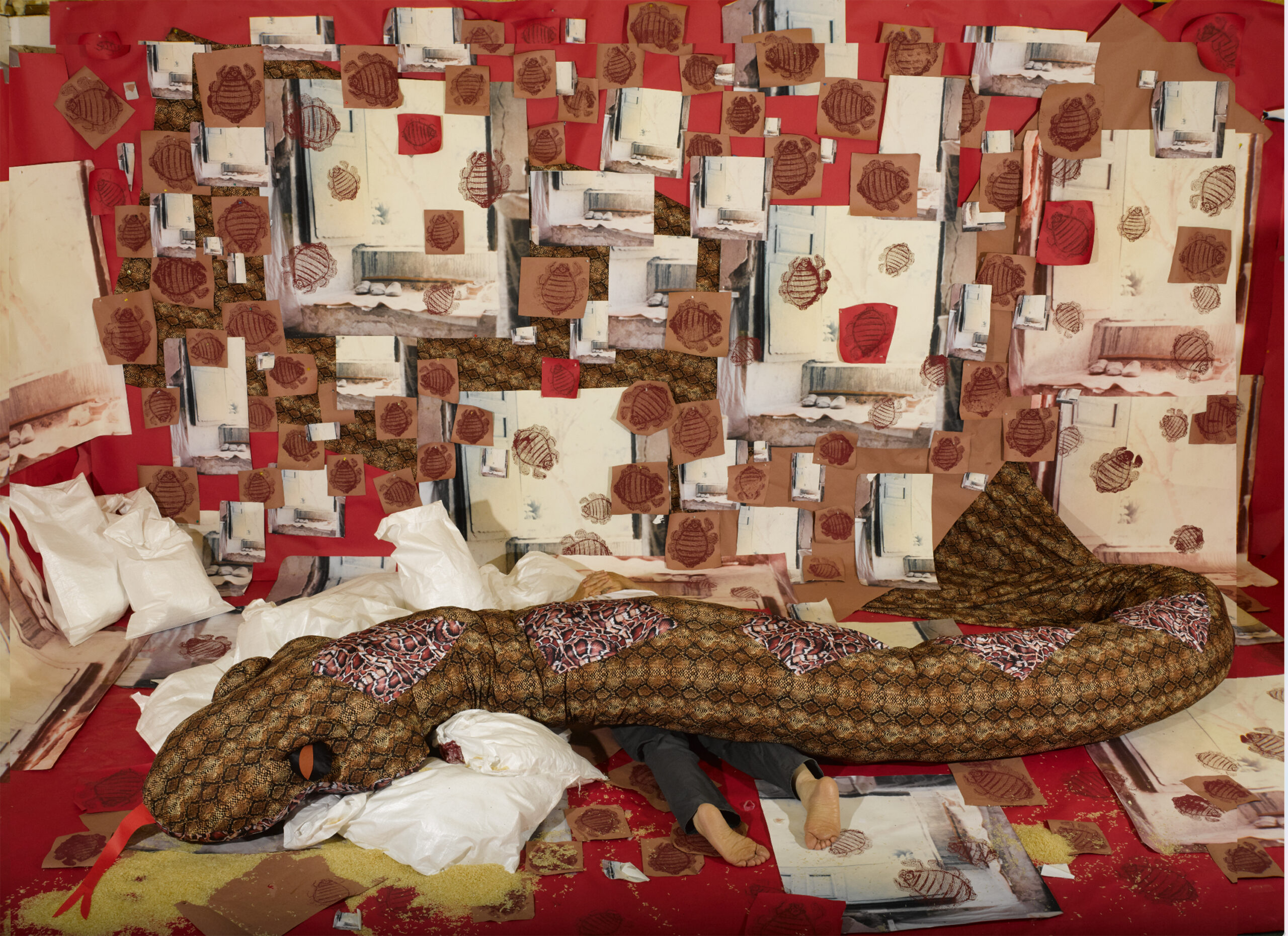

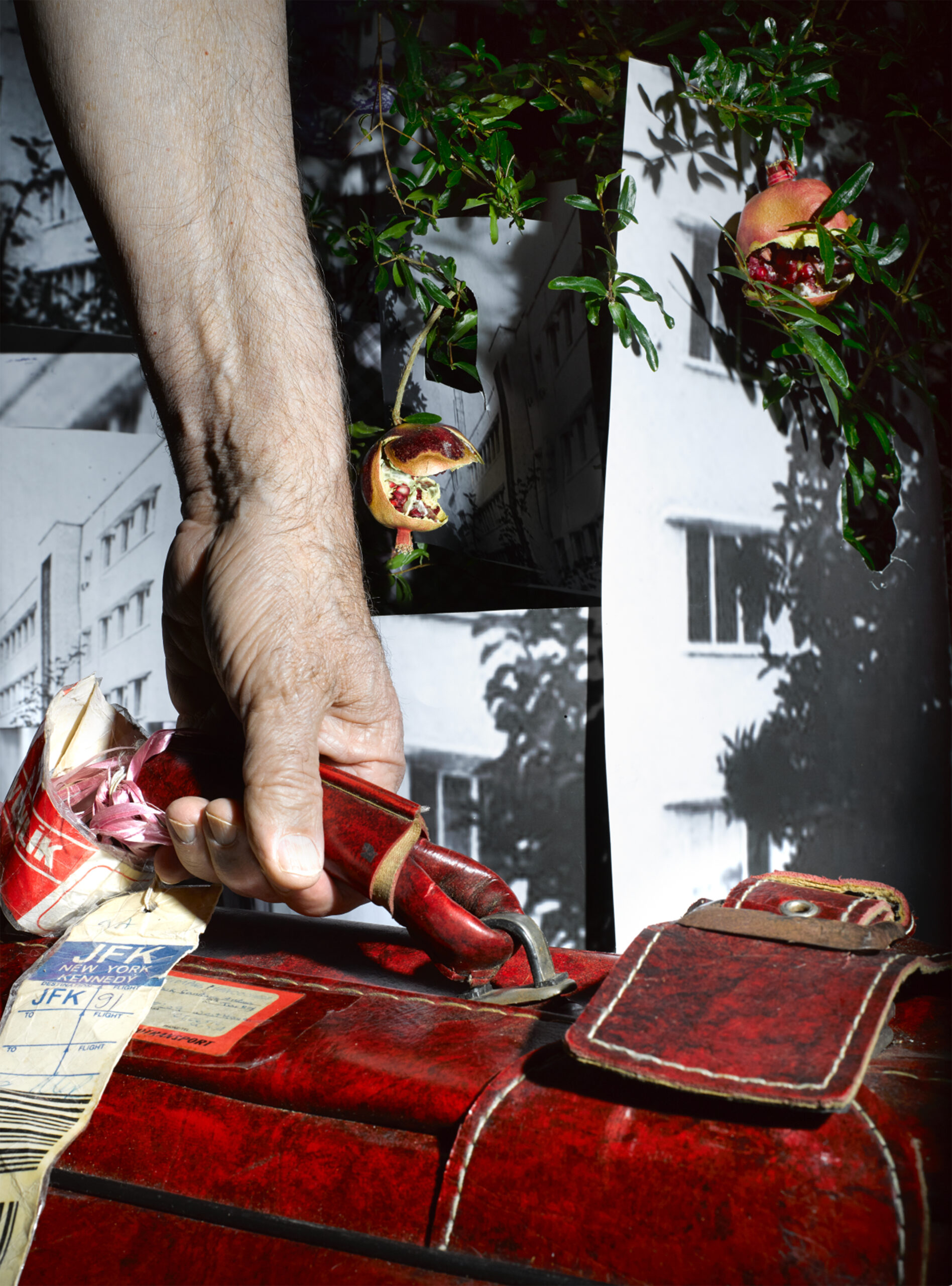

First presented to the public in her On the Wall solo exhibition at Providence College Galleries between March and October 2022, different iterations of Ghostwriter were subsequently showcased at London’s Edel Assanti, New York’s Denny Gallery (Birds of Passage) and Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts (Banner Projects), where it will stay through June 2024. Taking its title from Soleimani’s desire to “ghostwrite” her parents’ experiences of displacement in America, the series documents them within set designs rich with references to Persian iconography, other pro-democracy activists and their own rediscovered quotidian dimension. In the artist’s eye, her Bâbâ and Mâmân’s recollections of home manifest themselves in dense, surreal mosaics of meaning. If it weren’t for the easily distinguishable physical objects and creatures making up their compositions — including tree branches, colourful bits of paper, collaged photographs, birds, roosters, ladders, fake portals, rugs, old suitcases and drawings — a distracted viewer could misread the scenes gathered in Ghostwriter for glitched images only existing in the digital realm. Despite this not being the case, Soleimani’s latest work certainly feels oneiric and transcendental.

To keep the project suspended between dream and reality is the dual atmosphere permeating its public displays. If, on the one hand, any graphic representation of her parents’ identity has been deliberately concealed under the pastel-shaded, Henri Matisse-ish paper cut-outs placed on their faces throughout the series, the hand-drawn maps providing the backdrop for the different presentations of Ghostwriter offer more insights into their life journey.

The debut installation of the series saw Soleimani’s Dada-inspired tableaux inhabit a hand-drawn sketch of her mother’s childhood house and its courtyard, “where my father went into hiding for years”, she says. Based on an original drawing by her Mâmân and expanding over the floor and walls of Providence College Galleries, the map depicted “the site where my mum had buried eight babies in jars of formaldehyde, under her favourite tree”. In the second iteration of the project, the escape route of the artist’s father — across Iran, over the Zagros mountains and, finally, into Turkey — plastered the interiors of Edel Assanti in a bright shade of petrol blue. Once out of the country, he managed to move to the US in 1983. While she wasn’t as politically active, his wife was imprisoned as a punishment for his dissidence and subjected to physical and psychological violence before eventually being able to reunite with him in 1986. Denny Gallery’s more recent exhibition took shape from the outline of the Shiraz hospital where the couple first met in 1975: a key location in the two’s entangled stories, the building became a theatre of resistance in the revolution.

Woven throughout Ghostwriter are a myriad of prints, fabric snippets, text excerpts and human shrapnel taking us in and out of Soleimani’s universe and their parents in a mysterious play of contrasts. Here, three and bi-dimensional ladders and front doors hint at Mâmân and Bâbâ’s suffered road towards a new beginning, while Persian motifs stand, at once, as a testament to the long-lasting influence of their traumatic experience and a manifesto of their Iranian roots. Of all the symbolism hidden in the work, the presence of birds — a key feature of traditional Persian art — and their juxtaposition with the disguised silhouettes of Soleimani’s parents voices the message behind the series. “In giving my parents (as both migrants and refugees) and migratory birds biographical and political lives, I do not simply seek to show that they suffer ongoing harm as life becomes non-life on planetary and national scales,” the artist says. “Rather, in opposition to the humanitarian pornography of pain, Ghostwriter treats these living beings as dignity-bearing subjects, agents and world-makers, portraying their stories distinctly and in tandem with one another to engender new ways of seeing, imagining and being in the future.”

Words by Gilda Bruno. Images courtesy of the artist, Edel Assanti, London, Denny Gallery, New York, and Harlan Levy Gallery, Brussels ©️ Sheida Soleimani