Your exhibition at Leyden Gallery is called Scopophilia. What led to the choice of such a loaded term as the title of the show?

I first heard the word years ago in one of my favourite films, Peeping Tom and I have been fascinated by its meaning ever since. I’m interested in how people interpret it and whether they moralize, recoil or sympathize with the notion of the morbid urge to gaze. I identify with it as part of the way I work—I like my interactions with models to be comfortable and congenial but the images I work become subjects with which I share a different kind of relationship because I can stare at every pore. I form a much more intimate relationship with this frozen character and probably impose or project a lot more of myself onto them because, by this stage, the relationship is unidirectional. This show, in particular, is a collection of work which objectifies or idealizes the body in a way I admit is slightly voyeuristic, and I have tried to explore some of the dynamic between the viewer, artist or watcher, and the subjects who know they are being watched.

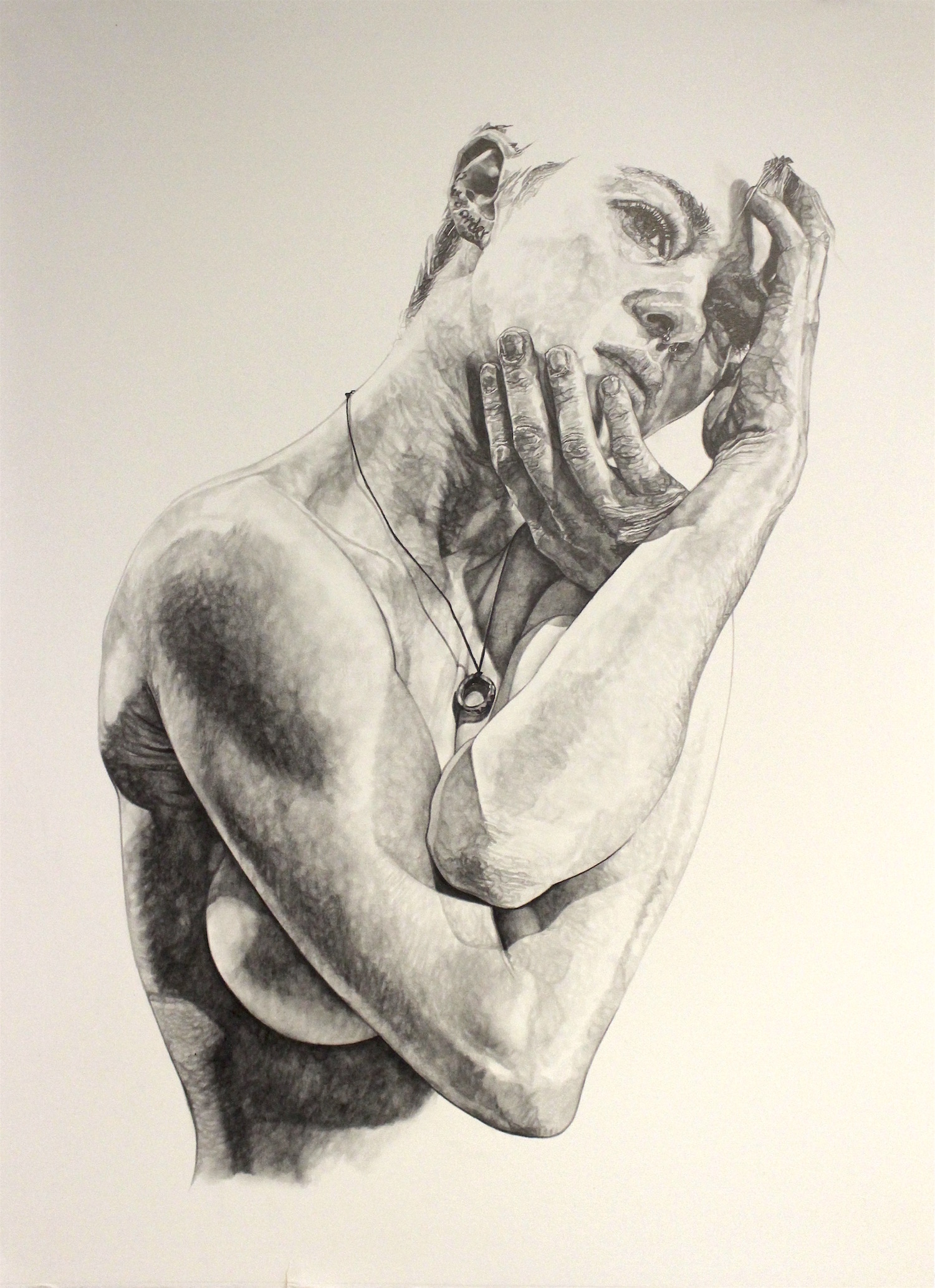

Stigmata, acrylic on board, 60 x 84cm, 2017

Gender and sexuality often play a role in your work. How do they interact with this concept of scopophilia? Are you deliberately playing with—and subverting—the idea of the male gaze?

Yes, that was part of my thinking. I’ve grown up with a very entrenched idea of classical poses and, while I find these beautiful, I also see them as characters in a completely different universe. Figurative art is inherently sexually charged and I find it fascinating that it’s given special license for this while simultaneously having incredibly fixed conventions that dictate what is and isn’t acceptable—particularly according to gender. My experience of sexuality is different, it’s subtle, and I try to slightly subvert expectations about who is in control, which features of the body to sexualize and whether the subject is dominant or submissive. Often I find that ambiguity is the most compelling aspect of the work—and of relationships in reality. I like to use performers who control the space in the painting and knowingly invite you to look, remaining untouchable, or to try and imply a private moment—that delicious fragile feeling that you are watching while the subject knows they are being watched but both are feigning ignorance. This is a conventional device in classical art catering only to the male gaze. My perspective is the antithesis of this.

“I’ve grown up with a very entrenched idea of classical poses and, while I find these beautiful, I also see them as characters in a completely different universe.”

How different an experience is it for you to paint a man as opposed to a woman?

I think there’s an inevitable difference in the way I approach subjects of different genders simply because the features I fixate on in each differ slightly. However, the reason for choosing many of the people I do is often because they subvert the expectations of gender, for example, physically strong women or men who play with stereotypically feminine poses or costume. The quality of skin texture is often very different, meaning I need to make different marks in order to illustrate this, and I think I am probably more conscious of the way I present women’s bodies—I don’t want them to feel disingenuous because of expectations I’ve inherited or accumulated from classical art or contemporary media.

A lot of your subjects are quirky in some way or belong to a subculture. Do you deliberately seek out such people?

I just get a feeling about people, which is probably guided by my own cultural predilections and tastes. I think I’ll always be more drawn to people who rebel or experiment in some way with their appearance because it’s energizing and uplifting to be around people who seem less repressed and a little more expressive. An opportunity to learn about or integrate myself into a new community is something I’ll never pass up and I see it as a perk of my job that I am permitted to go exploring where others might feel a little out of step.

“The flesh of the body is one of my favourite things to paint. I get completely engrossed with layers of tissue and colour.”

You’ve said before that you like the tradition of figurative artists as documentary. Do you see your paintings as objectively representing some truth?

It’s fascinating that whether paintings are surreal, narrative, realistic or portrait-based they always reveal some aspect of the cultural context of their time. I am making a record of people who, in some way, impact the culture I am living in now. I think they are often identifiable as contemporary figures even when they have very little context to provide clues. Tattoos and piercings and their style, placement and coverage are significant to the place and time in which they were made. The age and stage of the people I choose is often scarily similar to my own because I choose people by instinct rather than by design, so, in a way, I am documenting a particular stage of both our lives and I think I impose these things on the work because we discuss it when I take photos or make preliminary sketches.

Skin seems to be a significant surface in your work. Often it is tattooed, scarred or marked with rope burns; at other times it is almost translucent, showing a fretwork of veins and muscles beneath. It seems to carry almost more defining detail than the eyes, nose or other distinguishing features.

I think the detail and features of the face are something I want to articulate with as much accuracy as possible but I try to avoid photorealism because the harder I stare, the more I see abstraction, so I try to achieve both likeness and abstract shapes and pattern when I paint faces. The flesh of the body is one of my favourite things to paint. I get completely engrossed with layers of tissue and colour because it satisfies my anatomical curiosity but also conveys something vulnerable about the subject. I get completely and very happily lost in the contrasting textures of soft and rough skin, the aging of tattoo ink, the contrast between the texture of fat and muscle and the fleeting pressure marks, bruises, scratches or scars in flesh. Knees and the soles of feet are particular favourites and they’re often the things that visually remind me of other senses such as touch or smell, so there’s something very specific and challenging about trying to capture that sort of detail. I also think it’s a sign of remarkable trust that the people who pose for me are happy to expose those parts of themselves as, to me, that’s far more intimate than nakedness.

The painting Stigmata seems somewhat different from your other work. Can you talk a bit about this?

I see paintings of Christ as a good vehicle to communicate a particular kind of male beauty and I wanted to choose a model who was beautiful and slightly androgynous and to use the stigmata as a decorative element rather than an expression of suffering. Resurrection images are so far removed from true suffering and so absurdly glorified that they possess no realism or catharsis—more a study of the pleasure of pain or sadomasochistic pleasure-pain without consequences. I wanted to reduce the significance of suffering even more by using gemstones rather than blood. Andrew, my model in this painting, has an incredibly penetrating but compelling stare. I wanted to capture something of the connection I felt with him. The background references Giovanni Bellini’s Resurrection of Christ. I want it to look a bit like a theatre backdrop because the scene is entirely and knowingly performative. I would like to work more with religious imagery because the poses and scenes are so ubiquitous and immediately recognizable and I can’t resist a little irreverence.

You’re also painting a portrait of Anne-Marie Imafidon, a girls in science campaigner and CEO of Stemettes, a social enterprise working across the UK and Ireland to inspire and support young women into Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths (STEM) careers, for the University of Oxford as one of twenty-five portraits for their Diversifying Portraiture initiative. How did you become involved with this?

There was an online competition for the project so I sent examples of my work, wrote about why I would like to take part, and luckily I was chosen. Oxford wanted to recognize the diverse and complex identities that are often left out of the collection of dusty portraits that adorn the university’s walls. They have now unearthed and catalogued a collection of about 250 historical portraits, many of which challenged the stereotypes and exclusions of their time. The idea is to build on this legacy by commissioning portraits of living Oxonians of varying abilities, sexualities, genders, ethnicities and socioeconomic backgrounds. I was keen to make something that would be part of a permanent collection and also to attempt a more formal project that contrasts with the requirements of my usual work but stays true to its values and aesthetics. It was a really interesting brief and my subject is amazing. I can’t wait to see what the other artists have come up with and, I have to admit, I love the idea of having a piece on the walls of such a beautiful building.

Scopophilia will run at Leyden Gallery, London, E1, from 4 October to 4 November