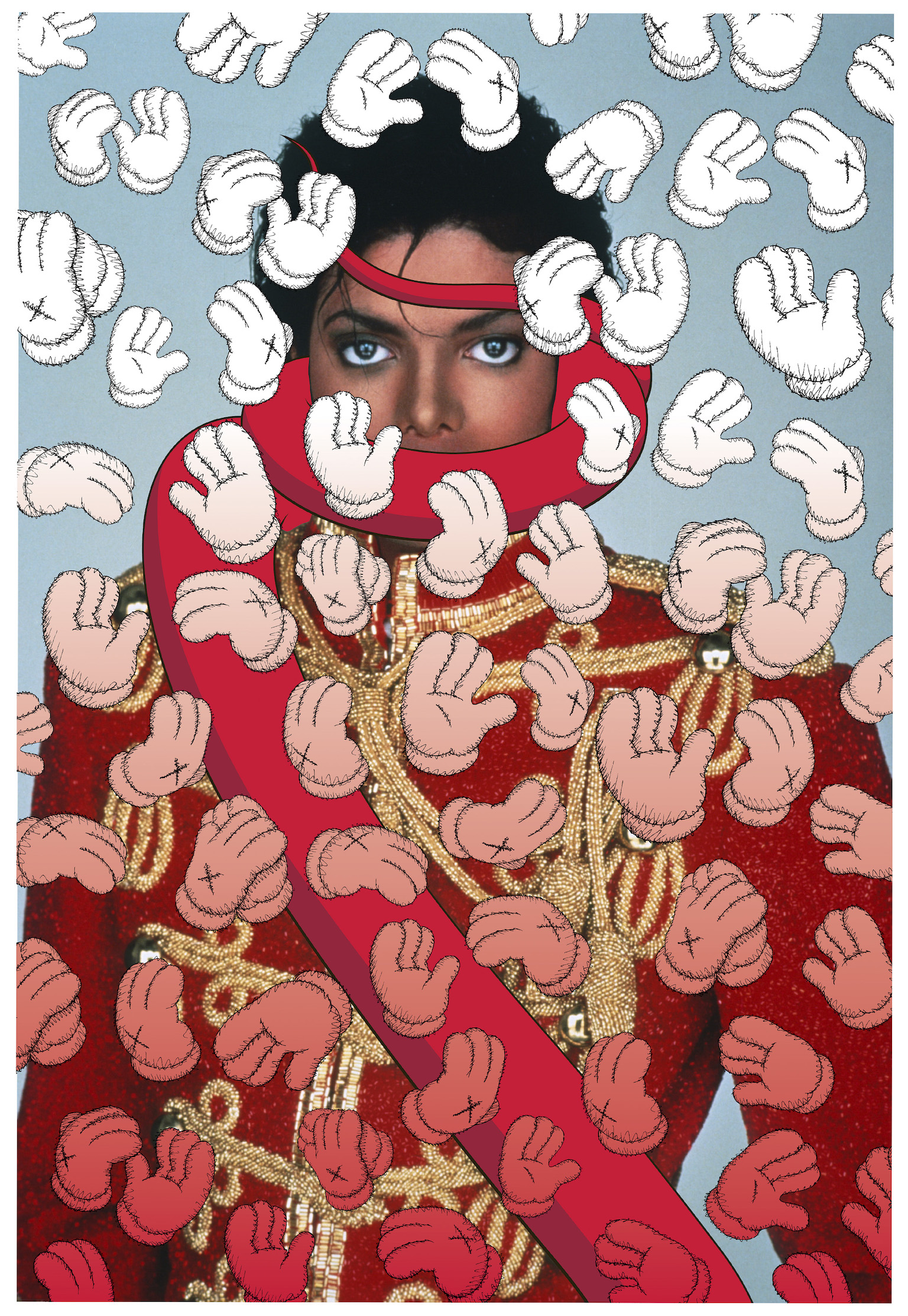

I don’t often refuse to enter an exhibition. But in the summer of last year, I found myself maddened at the EMMA museum in Finland where the touring exhibition (first staged at the National Portrait Gallery in London in 2018) Michael Jackson, On the Wall, was on display. I had recently watched the deeply disturbing documentary, Leaving Neverland (2019), which has prompted ferocious debate over Jackson and what he might have been capable of. The idea of admiring his work after seeing it made me feel physically sick. I decided not to see the exhibition and felt outraged that a museum would go ahead with it in light of the alleged sexual abuse of children.

Leaving Neverland came out three years after the planning for Off the Wall began at the National Portrait Gallery, but museums in Europe have continued to put the show on as planned since. It has been widely touted as a “celebration” of Jackson, the “King of Pop.” Why would we continue to laud Jackson in public, following the very direct accusations that are unresolved but still unavoidable? In Jackson’s case, it feels as though enough is enough.

Arja Miller is the Chief Curator at the EMMA museum in Finland, where the exhibition on Jackson’s life and legacy is currently showing until the end of the month. “What we originally found intriguing in the exhibition was the quality, diversity and also the critical nature of the artworks, the impressive list of leading contemporary artists from different generations and nationalities, and the range of themes they have examined through Jackson. This hasn’t changed. The exhibition shows almost 100 works from forty-eight artists. For us, it was important that the exhibition is not biographical or celebratory and doesn’t put Jackson on a pedestal. Instead, the show is an art-historical survey about his impact on our culture by a diverse group of artists from four decades. Through their works, the selected artists discuss themes such as identity, race, gender, equality and also, the flip side of fan culture.”

Miller explains this diplomatically, and not without a certain weariness. Undoubtedly, she has had to answer similar questions from the press in the last months. But I still don’t find the response satisfactory. The exhibition is still celebrating Jackson’s career, but there is nothing mentioned directly about the accounts of abuse or the documentary in the materials introducing and presenting it. If the public aren’t fully informed about all of the aspects of Jackson’s life, how can they engage in proper critical viewing?

I cannot imagine how it would feel to see your abuser given this kind of public platform. Even among the group of journalists present at the exhibition, some were not aware of the documentary or accusations against Jackson and discussed doing a “nice piece” on it. The exhibition contains the responses of artists, that EMMA says are both positive and critical, but no matter which way you cut it, giving such space to someone’s work smacks of validation—no matter what they may have done. And here is the profound problem: there is nothing that curtails male “genius”. If you’re a man with great talent, there’s no line drawn anywhere, not at child abuse, nor incest, nor rape.

“The allegations against Michael Jackson were not new. Jackson has been a subject of controversy for decades already and some of the artists in this exhibition are referring to these accusations,” Miller posits, mentioning Jordan Wolfson’s inclusion in the group show, which uses broadcast material from after the 1993 trial against Jackson. “The earliest works in the exhibition were made in the eighties, and since then Jackson has been a fairly frequent subject in contemporary art up to this day. He was and still is a complex character and undeniably also a talented performer and artist. The emphasis in the exhibition is, however, in the artists’ multiple interpretations on Jackson as a cultural icon, and how its reading has changed over time.”

“If you’re a man with great talent, there’s no line drawn anywhere, not at child abuse, nor incest, nor rape”

Hannah Gadsby exploded the question of art history and abusers, by unmasking the misogyny in the way we have mythologized Picasso, in her 2018 Netflix special Nanette. As an art history student, Gadsy was enraged by the way Picasso’s sexual past—including his affair with a seventeen-year-old when he was forty-five—was revered, as if the older male artist had the right to prey on younger female muses. This dynamic has been normalized through history in the way these artists are exhibited and written about. Yes, these artists were important and influential at the time—but it is rare to read the word abuse.

Artists still list Picasso’s greatness left, right and centre, undeterred by his grimy biography. A new exhibition of more than three hundred works by the artist opens at the Royal Academy this month; it includes reference to the “seeds” of his masterpieces without mentioning the fact Picasso was powerful and he used that influence and power to disenfranchise and abuse others. Why are we so fixated on this being “a dilemma”? Why should we separate the art from the artist—especially when their abuse clearly makes its way into the work we continue to talk about? Meanwhile, when there are plenty of “complex” and “tormented” artists (as these abusers are often characterized) who have been overlooked, who did not commit abuse, that we can give space to now. If they can be erased for no reason, why are we so concerned with giving proper discussion to people who built their artistry on others’ pain?

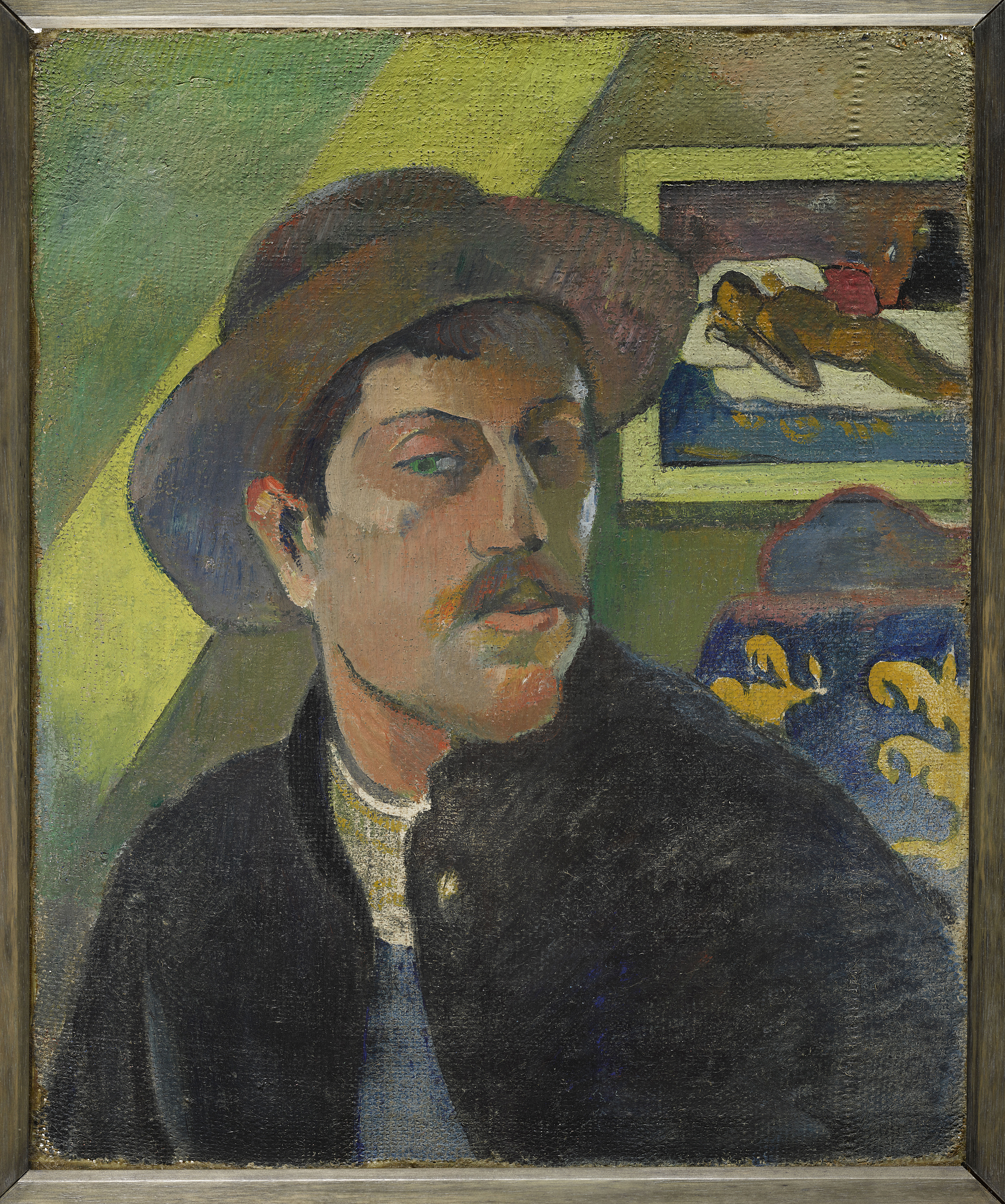

Paul Gaugin, like Picasso, was a colonialist and misogynist whose patriarchal, objectifying perspective of women was painted blatantly onto his canvases. Gaugin moved to Polynesia from France so that he would be free to indulge in his own exotic and erotic fantasies. He married three girls, all aged between thirteen and fourteen, and gave them syphilis—the illness that eventually killed him. These children also served as models and muses for his paintings. One of them, Teha’amana a Tahura, features in a portrait that has been used to advertise the current exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery, Paul Gaugin Portraits, without explanation of the relationship between the painter and the subject. There is no mention of the abuse or the child’s age in Elizabeth C. Child’s text for the exhibition.

Since 2010, numerous articles have consistently questioned Gaugin’s life and the problems with admiring his paintings, and there have even been widespread calls on the internet to “cancel” his legacy—and yet, the show goes on. In 2020, here we are, with yet another major Gaugin exhibition, at one of the world’s most important art venues. “Gauguin’s life and art have increasingly come under scrutiny, especially the period he spent in South Polynesia. The National Portrait Gallery has set out to explore this controversial subject matter in the exhibition interpretation and accompanying programme and to join conversations now taking place that consider Gauguin’s relationships and the impact of colonialism through the prisms of contemporary debate,” the NPG said in a comment.

This again sounds very neat, but is more discussion what is needed? What exactly is the debate here? The NPG’s advertisements and descriptions of the exhibition hardly frames this as what it really was—abuse. If it is possible to visit and leave an exhibition none the wiser to what was really going on in order to create these artworks then, in my mind, that is a failure. It only propagates the myth of the male genius. Gaugin was unequivocally a horrible man, who did horrible things, out of which he made beautiful and exploitative paintings.

These paintings don’t exist for themselves—they have also been extremely effective at sealing an image of how to look at non-western women in Europe, an image that has endured, proliferated and inspired others to represent women in a similar way. Gaugin is, to me, a nightmare of colonial, patriarchal, predatory abuse. There is no way, if he were alive, we would permit him to be shown and celebrated like this. Why should the fact he is dead and buried make a difference?

In 2017, Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft presented Eric Gill: The Body, in which they did openly cite the fact Gill sexually abused his two teenage daughters—a fact Gill himself detailed in his own diaries. The exhibition was co-curated by Cathie Pilkington and directly addressed the way Gill examined and explored the body in his art and how his abuse, and our knowledge of it, affects how we see and understand his work today, eighty years after his death. Even when an institute—Ditchling being a rare example—is unambiguous about an artist’s biography, is that really satisfactory enough? In the spirit of revising art history, it feels like time should be up for these artists who had their day but who we can now rightfully disown.

The role of art institutions in this is huge: it is here that artists are given value, in terms of finances, history and the future. It’s here that their views are validated—even when they are simultaneously drawn into question. Shows on this level repeatedly reinforce the idea that male artists are immune to the rules the rest of us must comply with because of their “great” and “undeniable” talent. The fact these artists are dead is an excuse that muddies the issue.

“There is no way, if he were alive, we would permit Gaugin to be shown and celebrated like this. Why should the fact he is dead and buried make a difference?

An argument I also frequently hear is that “it was different in those times.” That seems a convenient way out and anti-progressive, ramming home the same ideas about what it means to be an artist. The fact these abusers got away with their abuse and were able to build phenomenally successful careers makes it even more galling that they are still being applauded. Fundamentally, presenting an abuser’s work is a justification that if the art is good enough, that is what prevails. It all seems dubiously archaic to me.

“As an art institution, we are not trying to give one-dimensional answers. We are a discursive platform for art, artists and audiences and we still see this exhibition as relevant in that,” argues Miller of the EMMA. But when it comes to abuse, there is a very clear answer—and perpetrator—and there are very clear consequences for the people it affects. No amount of on-point discussion or relevant programming is likely to change that. The bottom line is that we still can’t seem to let go of the “important male artists” who have dominated us. Until we can write them off to where they belong—the past—it’s unlikely we’ll be able to change much about the way we see exploitation in the present.