You’ll have no trouble recognizing James Richards at this year’s Venice Biennale, where he’s representing Wales. He’ll be the one, he jokes, “crying squid ink at the opening” from the mountains of black pasta he’s been eating in the run-up. The Cardiff-born artist plans to spend four weeks onsite relying on his wits to come up with much of his show rather than having it all carefully crafted beforehand, which strikes me as quite brave.

“I like including this element of improvisational reaction to certain things that are happening with the other works in the space, and also the adrenalin of it. The fact that you have to find a solution keeps a certain sort of simplicity which I’m into,” Richards tells me over coffee at London’s ICA, the venue of his recent acclaimed solo show Requests and Antisongs. “If you overthink it, you end up making boring stuff.”

The Welsh pavilion will be presented in the deconsecrated church of Santa Maria Ausiliatrice and three adjacent rooms that belong to a working community centre. For the church, Richards is creating an orchestral composition from a piece of live percussive music produced with students from the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama that will be blended with the sounds of the space.

“In the other spaces, we’re almost certain that one of the rooms will feature a film work and that will connect to the other two spaces through more archival and film images, but he hasn’t quite determined that yet,” says the director of visual art at the Chapter Arts Centre in Wales, Hannah Firth, who is curating Richards’s Venice exhibition.

Besides images that Richards is currently amassing in archives in Wales and Berlin, they are hoping to uncover historic material in Venice about the area around the Welsh pavilion, once home to the highest number of boat-builders in the city. “There’s no formal archive,” Firth adds. “It’s more a case of trying to see whether any of these people have images stored away in a shoebox and so that might well weave its way into the work but we don’t know whether it even exists at this stage.”

What makes the thirty-three-year-old artist’s work so distinctive is the way Richards collides diverse found and original images and sounds with different technologies to form poetic, multilayered assemblages that flit between abstraction and representation. “A big touch point for me,” he notes, “is sculpture like Robert Rauschenberg’s or Isa Genzken’s or these kind of assemblage practices that are about gathering quite disparate materials and making them sit on each other. But it’s not really about making them become all one thing. They’re still all quite separate things.”

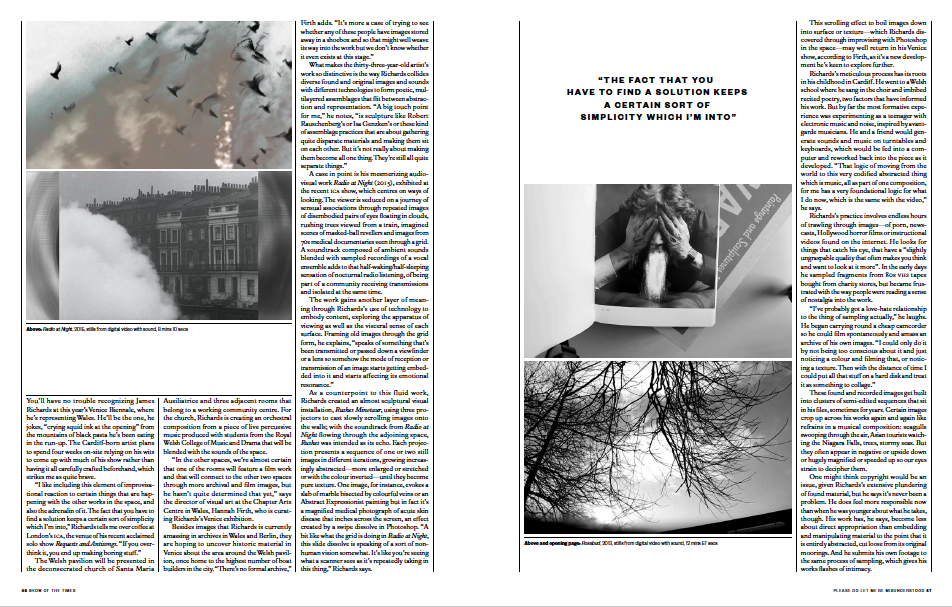

A case in point is his mesmerizing audiovisual work Radio at Night (2015), exhibited at the recent ICA show, which centres on ways of looking. The viewer is seduced on a journey of sensual associations through repeated images of disembodied pairs of eyes floating in clouds, rushing trees viewed from a train, imagined scenes of masked-ball revellers and images from 70s medical documentaries seen through a grid. A soundtrack composed of ambient sounds blended with sampled recordings of a vocal ensemble adds to that half-waking/half-sleeping sensation of nocturnal radio listening, of being part of a community receiving transmissions and isolated at the same time.

The work gains another layer of meaning through Richards’s use of technology to embody content, exploring the apparatus of viewing as well as the visceral sense of each surface. Framing old images through the grid form, he explains, “speaks of something that’s been transmitted or passed down a viewfinder or a lens so somehow the mode of reception or transmission of an image starts getting embedded into it and starts affecting its emotional resonance.”

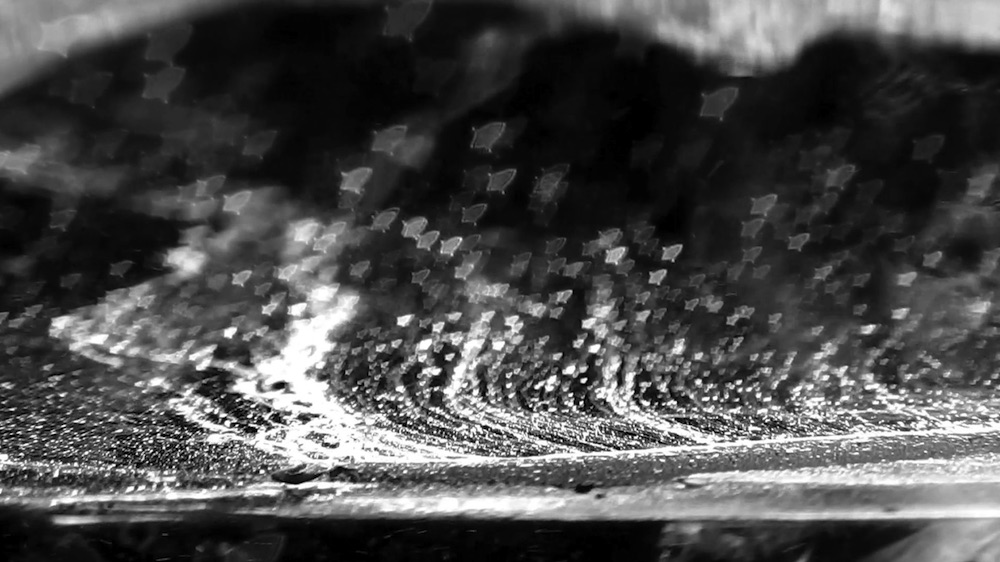

As a counterpoint to this fluid work, Richards created an almost sculptural visual installation, Rushes Minotaur, using three projectors to cast slowly scrolling images onto the walls; with the soundtrack from Radio at Night flowing through the adjoining space, Rushes was intended as its echo. Each projection presents a sequence of one or two still images in different iterations, growing increasingly abstracted—more enlarged or stretched or with the colour inverted—until they become pure texture. One image, for instance, evokes a slab of marble bisected by colourful veins or an Abstract Expressionist painting but in fact it’s a magnified medical photograph of acute skin disease that inches across the screen, an effect created by a swipe dissolve in Photoshop. “A bit like what the grid is doing in Radio at Night, this slide dissolve is speaking of a sort of non-human vision somewhat. It’s like you’re seeing what a scanner sees as it’s repeatedly taking in this thing,” Richards says.

This scrolling effect to boil images down into surface or texture—which Richards discovered through improvising with Photoshop in the space—may well return in his Venice show, according to Firth, as it’s a new development he’s keen to explore further.

Richards’s meticulous process has its roots in his childhood in Cardiff. He went to a Welsh school where he sang in the choir and imbibed recited poetry, two factors that have informed his work. But by far the most formative experience was experimenting as a teenager with electronic music and noise, inspired by avant-garde musicians. He and a friend would generate sounds and music on turntables and keyboards, which would be fed into a computer and reworked back into the piece as it developed. “That logic of moving from the world to this very codified abstracted thing which is music, all as part of one composition, for me has a very foundational logic for what I do now, which is the same with the video,” he says.

“Aesthetically that really interests me, that in and out, received and generated, influenced and produced, and all those things cut into one another”

Richards’s practice involves endless hours of trawling through images—of porn, newscasts, Hollywood horror films or instructional videos found on the internet. He looks for things that catch his eye, that have a “slightly ungraspable quality that often makes you think and want to look at it more”. In the early days he sampled fragments from 80s VHS tapes bought from charity stores, but became frustrated with the way people were reading a sense of nostalgia into the work.

“I’ve probably got a love-hate relationship to the thing of sampling actually,” he laughs. He began carrying round a cheap camcorder so he could film spontaneously and amass an archive of his own images. “I could only do it by not being too conscious about it and just noticing a colour and filming that, or noticing a texture. Then with the distance of time I could put all that stuff on a hard disk and treat it as something to collage.”

These found and recorded images get built into clusters of semi-edited sequences that sit in his files, sometimes for years. Certain images crop up across his works again and again like refrains in a musical composition: seagulls swooping through the air, Asian tourists watching the Niagara Falls, trees, stormy seas. But they often appear in negative or upside down or hugely magnified or speeded up so our eyes strain to decipher them.

One might think copyright would be an issue, given Richards’s extensive plundering of found material, but he says it’s never been a problem. He does feel more responsible now than when he was younger about what he takes, though. His work has, he says, become less about direct appropriation than embedding and manipulating material to the point that it is entirely abstracted, cut loose from its original moorings. And he submits his own footage to the same process of sampling, which gives his works flashes of intimacy.

“I guess this comes from this desire to collage from yourself, to treat the things that have come from your life the same way that you’d treat something from cinema. Aesthetically that really interests me, that in and out, received and generated, influenced and produced, and all those things cut into one another,” he says.

Perhaps it was this detached, egalitarian treatment of images, whether personal or found, that prompted über-curator Massimo Gioni, who included Richards’s work in his 2013 Venice Biennale show The Encyclopaedic Palace, to say of his collages: “There is something about them that is vaguely clinical—or deadly—as if Richards had dissected our civilization of images with the coldness of a forensic scientist.”

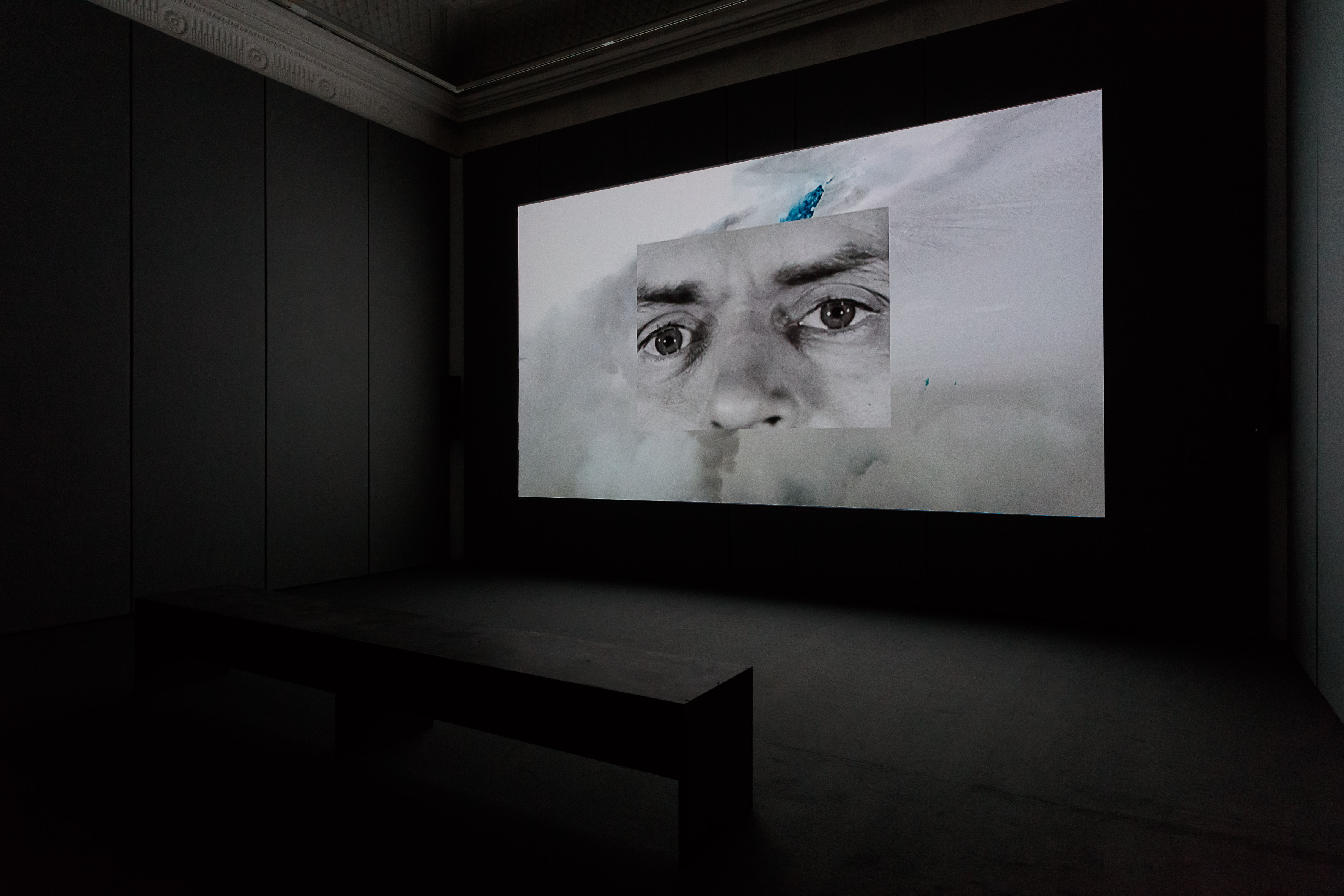

Certainly Richards’s works reflect the bewildering profusion of images and sounds that we experience daily, and his scrutiny of surfaces through extreme close-ups is indeed somewhat forensic. But his work is far from cold. Erotic desire—particularly homoerotic desire—runs through much of it, as epitomized by Richards’s Turner Prize-nominated video Rosebud (2013), whose title references the gay slang for anus.

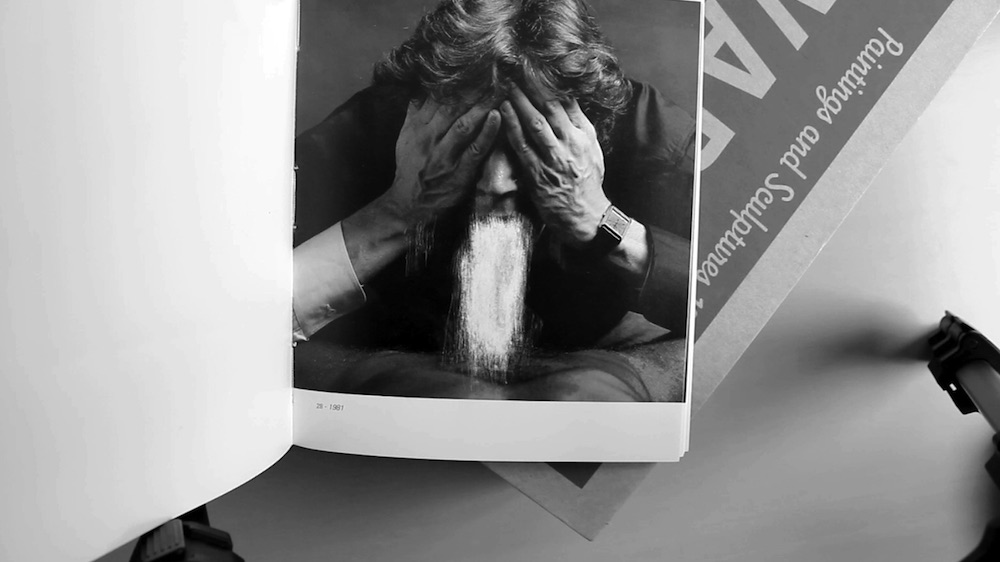

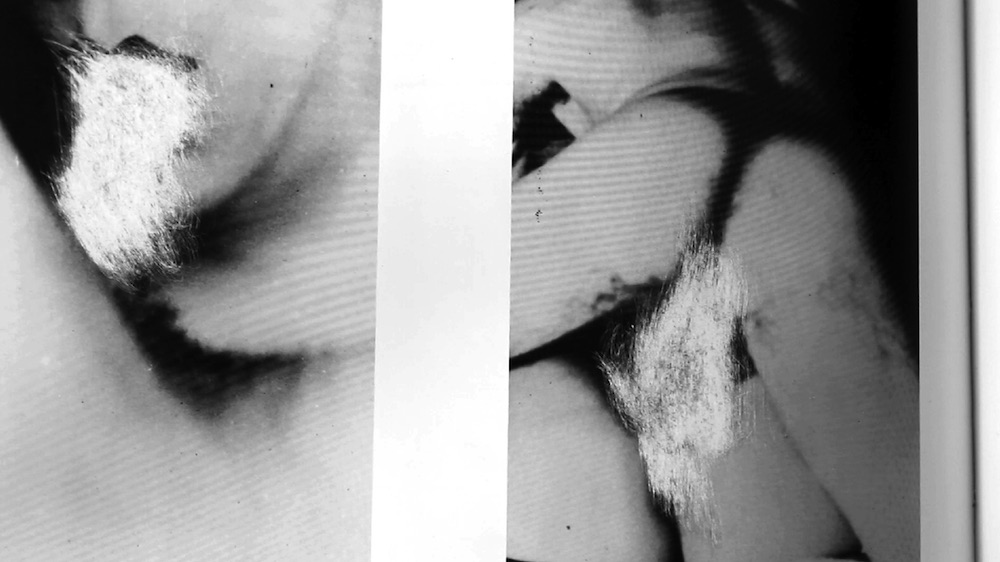

One of the film’s most arresting images is a black-and-white still showing what appears to be an elderly oriental man with a long white scratchy goatee, covering his eyes with his hands. This turns out to be an image from a book of Robert Mapplethorpe fellating an erect penis, which has been furiously rubbed away with sandpaper by Japanese censors.

Rosebud, 2013, stills from digital video with sound, 12 mins 57 secs

“The image was made out of the erotic and a desire to make an aggressively sexual image, and then that gets filtered through someone in another continent who is trying to remove all the things that make that image arousing and ends up speaking about rubbing and caressing,” says Richards, who came across the defaced images in a library during a residency in Japan.

“A recurring thread in my work is the treatment of an image in a way that there’s a sense of not really understanding, or misunderstanding, what the image is doing or was intended for,” he says.

“For me it’s often these shifts around things that are the most exciting thing, rather than a thing in itself”

This idea of “misintention” drives Richards to probe constantly around the edges of things, seeing how they might be challenged. Whether it’s shifting between different moving-image mediums or between textures or moods, the shifting becomes part of what the composition is about. “For me it’s often these shifts around things that are the most exciting thing, rather than a thing in itself,” he says.

An important departure was his Whitechapel show in 2015 where he was invited to respond to a work in the Russian V-A-C collection. Richards selected Francis Bacon’s Study for a Portrait (1953), depicting a suited man on a throne-like chair, engulfed by a midnight-blue background, and provided a soundtrack of silences—acts of mourning, pauses in films, singers breathing between songs—combined with vocal music, ambient sounds like church bells and percussive sounds, teeth chattering and cutlery clinking on china.

“I really loved that project,” he says. “It emboldened me to think about presenting this very stark room with adamantly no images, just cables and speakers, and giving very little visually but then giving lots in terms of sonic texture.”

That project gave him the confidence to do away with visuals entirely for his ambitious 2016 sound installation Crumb Mahogany, presented in the ICA show. Featuring six black speakers stationed around four benches, the work immersed the visitor in a sensorial soundscape that interspersed instrumental passages with ambient sounds and bodily sounds—from sung harmonies and smacking of lips to mutterings and heart beats—as well as sounds of electronic recording devices like Geiger counters, and shuffling of hard drives in a series of crescendos and ruptures. Although the piece was composed, it was very much in the spirit of Richards’s teen experiments with free improvisation.

“In the last couple of years I’ve been using exhibitions as ways of testing what I can do with my work, as a way of forcing myself to not resort to certain techniques and tricks which I am comfortable with in my practice,” says Richards. “I think that’s important as an artist.”

The Venice Biennale runs until 26 November.