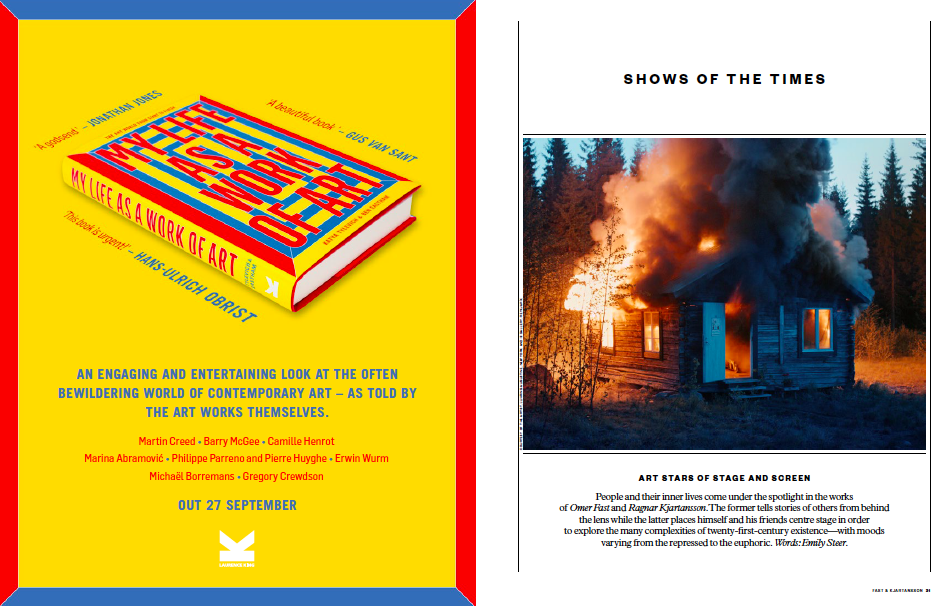

People and their inner lives come under the spotlight in the works of Omer Fast and Ragnar Kjartansson. The former tells stories of others from behind the lens while the latter places himself and his friends centre stage in order to explore the many complexities of twenty-first-century existence—with moods varying from the repressed to the euphoric. Words: Emily Steer.

This feature was originally published in Issue 28.

RAGNAR KJARTANSSON

Icelandic artist Ragnar Kjartansson’s multiscreen video work The Visitors—a feature of his current survey, which moves this autumn from London’s Barbican to Washington DS’s Hirshhorn Museum—sees the artist and his friends inhabiting a decaying mansion. The group fills the space with an hour-long musical performance, with each performer in a different room of the house and the artist nude in the bathtub. ‘His works bring together so many concerns that we have in the artistic world and the cultural world about crossing boundaries, about finding a sense of purpose to one’s action and being in a very complex world,’ Hirshhorn curator Stéphane Aquin tells me when we speak prior to the opening. ‘He touches on deeper human-condition questions, and he does so with grace, humour and intelligence. He also touches upon notions of cultural authenticity, spontaneity and kitsch without betraying himself on any level, without falling into sarcasm, cynicism or naive candour.’

I spoke to the artist.

Are you seeing new connections in putting the work together for your first survey show?

I see when you put them together that the form doesn’t matter so much as the content. The form is always pretty similar. I’m like any other artist, I repeat the form I work in very much, but I’m very happy with how the content works together. It’s like a book of poetry. But I’m also bewildered seeing the limits of the mind. I’m a simple man and I embrace that, but it’s revealing and I think it’s healthy to see it all together.

What is it about bohemia that excites you? It runs through much of your work, and is very prevalent in The Visitors.

I’m just trying to be a dedicated bohemian! That’s what I’m working on. I’m happy with it so far, I’ve managed to live a pretty bohemian life and it really comes into the work. It’s something I have always been fascinated by, it’s still one of those banal things that I find hilarious and so appealing.

Does a lot of your emotional self go into the work? It often feels as though you are experiencing it rather than illustrating it.

It’s always there. My emotions or more my view of the world. I think it’s my view of the world. Some of it becomes emotional, but emotion is such a complicated beast—where it comes from, what makes it emotional. I often use Mozart as an example: a lot of this crazy emotional stuff that he created was created with a tongue in his cheek.

You work with music a lot, you also draw, paint, perform. Is there a medium that you feel most at home with?

I don’t really know if I’m a painter or a performance artist. I started as a painter in art school, but then really found myself, found my niche where I belonged, when I started doing performance art. Performance art is what I have grown up with because of the theatre. I was always doing theatrical work and I think I went to art school because I sniffed that there was freedom.

You seem to create on a pretty mega scale.

I love the situation when people are trying to make something that massive. Just a ridiculous, decadent situation. I’m really fascinated by those situations and I get myself into them from time to time. The group situation seems to happen a lot also.

Is it important for you that the people in your videos have a personal relationship with you?

Not really, it just often is like that. I’ve also made work with people I have no personal relationship with, but then it’s a personal fascination with them. The personal relationships are also based on fascination. I’m just… How do you say this in a non-sentimental way? I just love people. It’s as simple as that. Creating stuff is a perfect excuse to have a good time. That’s how we humans have the best time together, when we work together on something. Be it building a barn with your friends, or working on a play, there’s always this great energy that’s created.

Do you hope to pull the viewer into that as well?

Sometimes I use multiscreen, and I want stuff to surround people in a Stockhausen-esque way of spatial music. I want it to be really directional and I guess being drowned in sound really appeals to me, but it also appeals to me to be aloof. I think I want to be both.

There are a lot of public comments on your videos on YouTube by people saying the work made them cry.

I like to work with the emotional response that is created. Some works are super-emotional and others are much drier on the surface but are much more emotional on their inner lining. I’m not aiming for the emotional but sometimes I dabble with it because I find it interesting. Then again, I also find it a bit disgusting when I, as an artist, am dabbling with the emotionality of the viewers. It is so not what you’re supposed to do as a visual artist. I’m always trying to be a bit complicated under a very banal, simple surface, but I don’t want people to cry. That’s rude and demanding.

Can I ask about the influence of Dieter Roth on you? You’ve spoken about him quite a bit before.

He is a big influence, yes, my work is really made as a response to lots of artists of that period. Often I’m also super-inspired by what he hated. He hated Halldór Laxness, who is my favourite author. Dieter was all about truth. I love Dieter, he is a part of my DNA, but I choose to differ with Dieter that truth is so simple, and therefore I choose to find truth in the lofty, ironic, pretentious writing of Halldór Laxness. Truth doesn’t need to sound like Hemingway, do you know what I mean?

‘Ragnar Kjartansson’ runs from 14 October 2016 until 8 January 2017 at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington DC.

OMER FAST

I’m watching an early screening of Omer Fast’s new feature film, Remainder. Five minutes in, an almighty thud occurs as the protagonist is knocked out by a falling object, which delivers him a watermelon-against-a-wall kind of whack around the head. The audience experience a mutual tensing, which doesn’t leave us until the end of the film. A week later I find myself at Gateshead’s Baltic gallery, speaking to the Jerusalem-born artist and filmmaker about the second instalment of Present Continuous—previously housed in Paris’s Jeu de Paume and on the move this autumn to the Kunsten Museum of Modern Art, Aalborg. The seven-video show hasn’t been set up in its entirety, and we move from room to room witnessing the install, enormous screens lining full walls. As we enter one space we see the final seconds of Everything That Rises Must Converge, the floor-to-ceiling, multiscreened climax of its subjects—porn actors—hard at work. It’s a fleshy assault on the senses that has an impact on even the porn-desensitized twenty-first-century audience. Viewers of Fast’s work should always expect aftershocks.

When making a feature film like Remainder you know that people will watch it from beginning to end. Works shown in galleries are a different matter. Do you approach filmmaking completely differently for an exhibition context?

The films that are shown in this exhibition are conceived and structured in a way where it’s known that they’ll be seen in a loop. I play around with causality and temporality in a way to include this notion that somebody’s going to come in at any moment. What’s fun, and possibly perverse, about this is that you can have audiences coming in at different points and coming out with a different understanding of what’s happening in the work, and then quite possibly comparing their experiences and understanding, and then aligning them accordingly. That’s a very ideal situation.

Do you always have a specific structure in mind when you make these works?

It really depends on the work. I would roughly divide them into works that are conversation- or interview-based, and fantasy/script-based. If I’m scripting something from scratch I get to think about the subject freely and create a text that I think about temporally and spatially, and then I film it, edit it and am in charge of what’s happening. In a conversation- or interview-based piece I come at these people very often whose work I find interesting and they’re sort of portraits of different workers. [In Present Continuous] we see portraits of three different workers in three different industries in North America. We have the story of a drone operator [5,000 Feet Is the Best, 2011] who talks about his life and work, we have funeral-home directors [Looking Pretty for God, 2008] who talk about their life and work, and we have adult film performers—who don’t really talk, they do other stuff!—who show us their life and work.

How do you tend to come across these people?

I don’t know these people personally, so sometimes it’s curiosity, and in retrospect I can find commonalities in why I’m interested in them. They’re all liminal figures, they all straddle a border of some sort and often it’s a border between visibility and invisibility. It means the work they do is often very taboo.

In terms of getting to the truth, or reality, of the stories people are telling, do you feel you differentiate when you’re speaking to a real person about their experiences and when you’re writing stories?

I think as long as I’m making work for this kind of context, what I’m most interested in is creating something which is a hybrid, which is neither/nor. I think the notion of what truth is is extremely critical for us as a society. Journalistically and juridically we need to know that we have institutions that function along lines that use truth and truth-finding. But I think with art the truth we’re after is a much more slippery truth. It looks at the relationship of what contamination does, of images and realities; at the stories we tell ourselves as a society when we send young men and women to war, or when we send them in front of the camera in order to fuck each other for our entertainment. I think that’s what art is trying to look at; the underside of that. It’s a truth that’s highly compromised.

‘Omer Fast: Present Continuous’ runs from 24 September 2016 to 8 January 2017 at the Kunsten Museum of Modern Art, Aalborg.