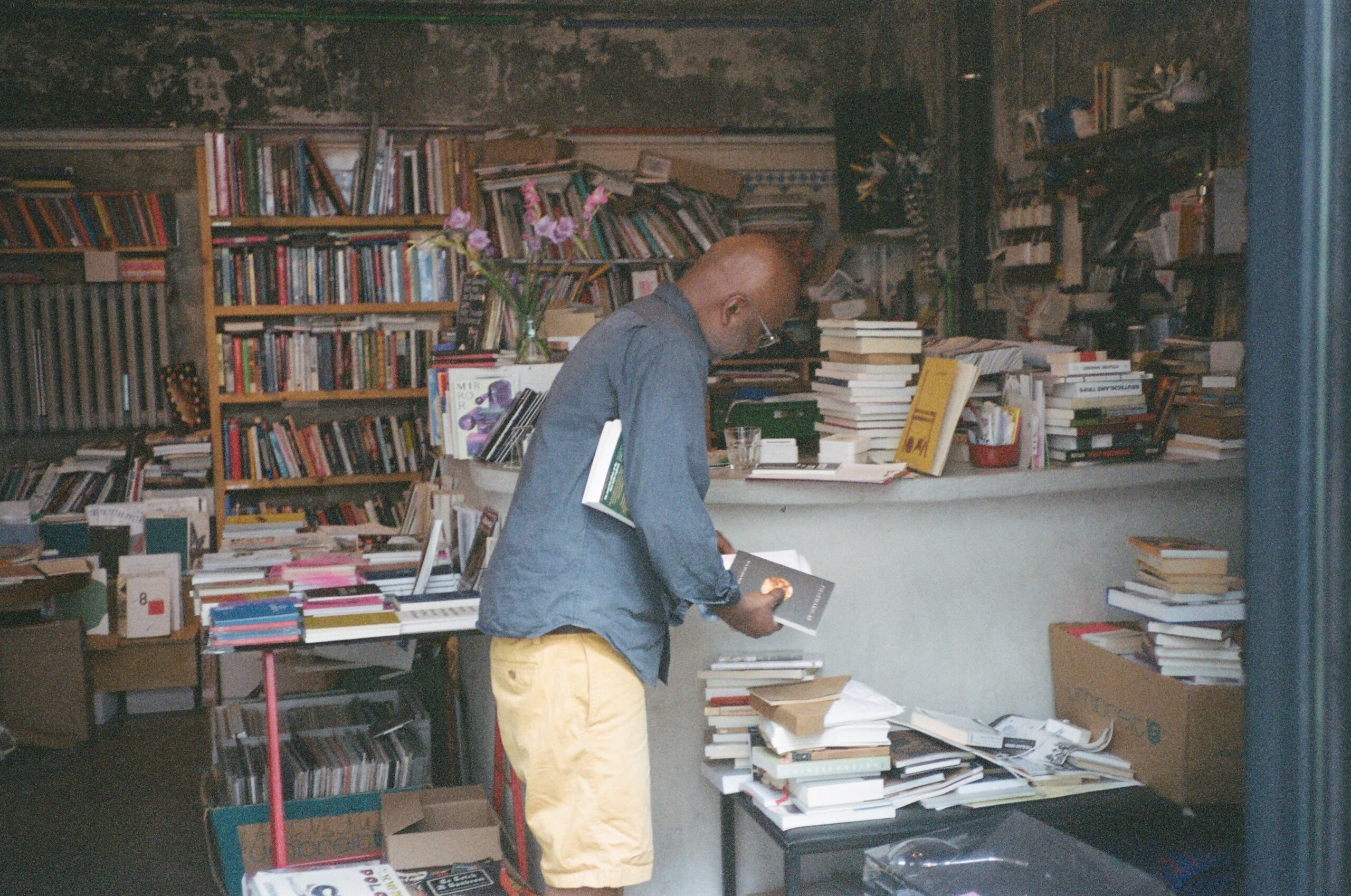

Siddhartha Lokanandi is more of a pharmacist than he is a bookseller. Over the two days I spent sitting in his Berlin-based bookstore, HOPSCOTCH READING ROOM, I watched Lokanandi work. Here I listened to his customers’ ailments, each a patient searching for the perfect book to soothe their afflictions.

Siddhartha Lokanandi is more of a pharmacist than he is a bookseller. Over the two days I spent sitting in his Berlin-based bookstore, HOPSCOTCH READING ROOM, I watched Lokanandi work. Here I listened to his customers’ ailments, each a patient searching for the perfect book to soothe their afflictions.

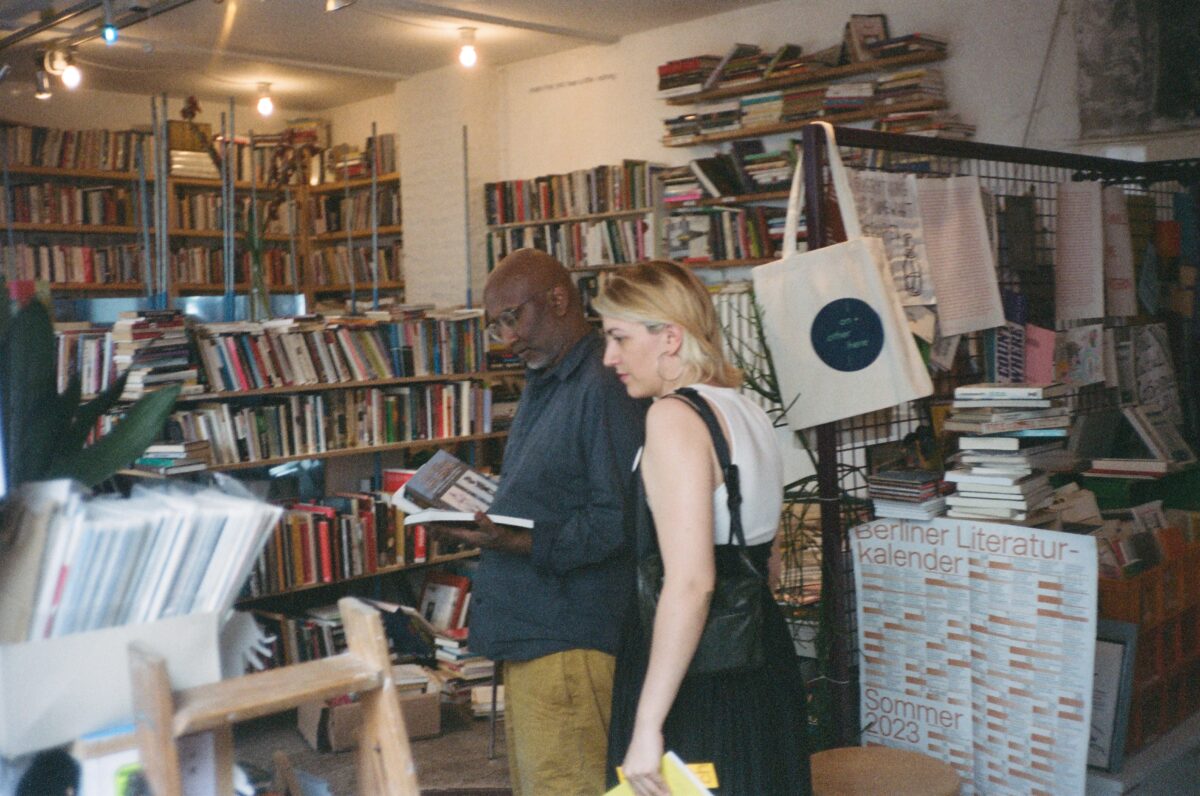

The first was a young Danish woman searching for a book on pre-colonial art in the Congo. “Do you speak French?” He asked as if asking if she smoked or if she had a history of heart disease. “No,” she responds, fearing the diagnosis. “Well,” he said, unsure how to say what came next, “You’ll need to know French for that because most of the work that has been written on that subject has been done by French-speaking academics. Very little of it has been translated into English because they have no interest in doing so.” She’s crestfallen—Siddhartha was clearly her second or third opinion. Unlike the others, though, he had suggestions, temporary remedies. He sifted through the shelves, finding works that weren’t quite as primary but enough to work around the limitations of being forced to learn French.

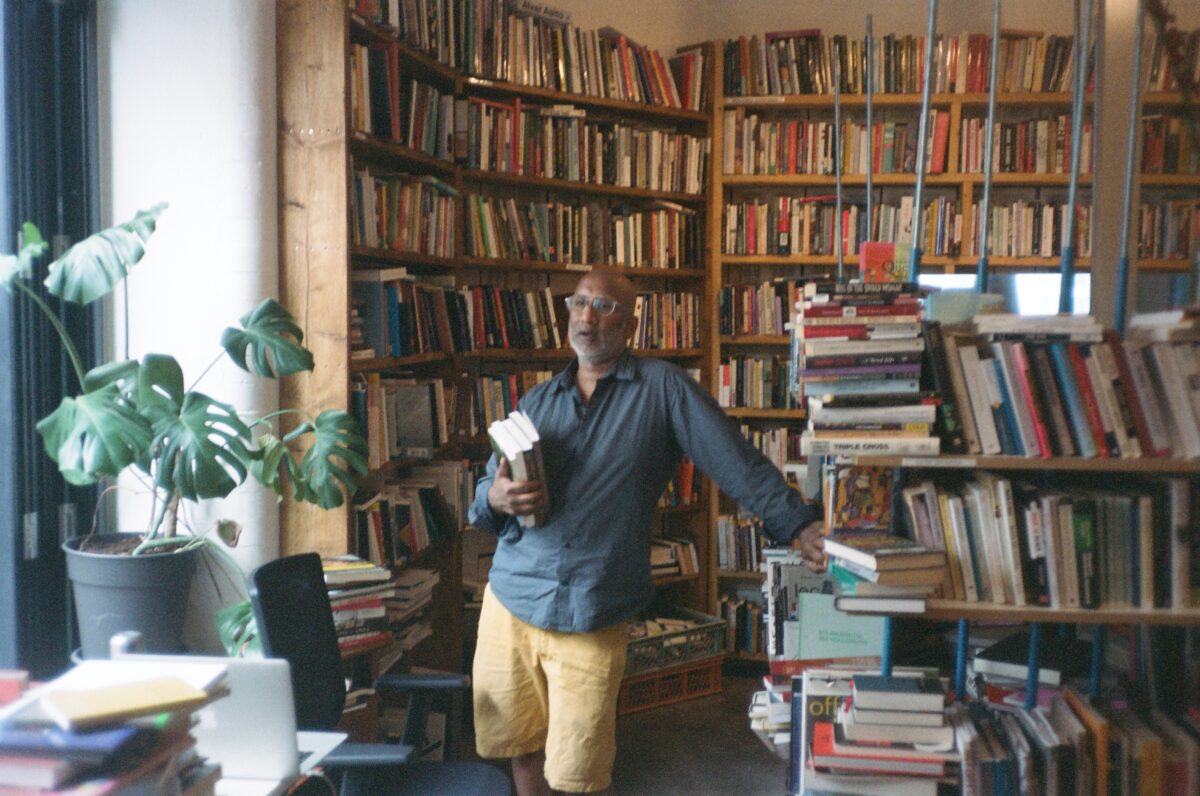

I met Siddhartha through a friend who knew him from New York, where I now live. When I first met Siddartha, it was my second day in Berlin. I greeted him and asked him how he was doing. “Fucking hot, man.” He said quickly, “You want a beer?” It was a sweltering 95 degrees in Berlin, the first day of what turned out to be the worst heat wave Europe has ever experienced. He crouched behind the counter, which was covered with books, behind a table covered in books, surrounded by shelves and shelves and shelves of books, almost entirely made up of the collection he had amassed after fifteen years in New York.

Berliners travel far and wide to seek Siddhartha, the American bookseller with an immaculate collection of English literature whose shelves include many titles that are now out of print. But despite this, he seemed somewhat wary of my intent to interview him, almost as though he was under the impression that I was only interviewing him as a favour to Natalia, my host whilst I was in Berlin, who had introduced me to Lokanandi, describing him as: “one of the most brilliant men she had ever met.”

Siddhartha was born in Orissa, India. He was named after the Hermann Hesse book Siddhartha, which his father had discovered from the hippies that visited India inspired by The Beatles and their experiences with Maharishi. Siddhartha followed the wave of Indians that first left the US at the beginning of the Internet age for jobs at Google and Adobe. His father, who died while Siddhartha was studying at Clark University in New York, was a low-level manager at the one company he worked at for his entire life. His mother was a librarian, and after his father’s death, Siddhartha dropped out of school to work in New York so he could move his mother to live with him in the US, where she continued to work as a librarian until she retired.

He found work at a new bookstore, Labyrinth Books, now Book Culture, on the Upper West Side, which served the Columbia University community. “It was really a great time to be in New York,” he said of the ’90s. “New York is like Bombay, where I also grew up. So there’s a lot of similarities, a lot of density, texture through multiple communities living together, segregated in some ways, united in some other ways. But the best thing about New York, I think, is the fact that you can walk the city and be a part of the city. That’s why so many people have written books about walking in the city. And for me, it was good because I worked at a bookshop but could always find more cheap books on the street, which is kind of the root of this collection.”

I first arrived at the store in time for a reading by Zain Khalid, an author from New York and editor at The Drift, a sexy, new, sophisticated literary magazine. Before the reading began, I was met by a group of men chatting outside- two Americans and a German. We spoke about how much better Woodcutters by Thomas Bernhard was in the original German than in its English translation, AI (which at this point should be marked as the writer equivalent of “don’t bring up sex, politics, or religion at the table”), and whether or not writers have groupies (they do, but they only want to sleep with you to talk about Henry James in the morning). Then, finally, Mr Khalid read from his new book Bother Alive (it was excellent).

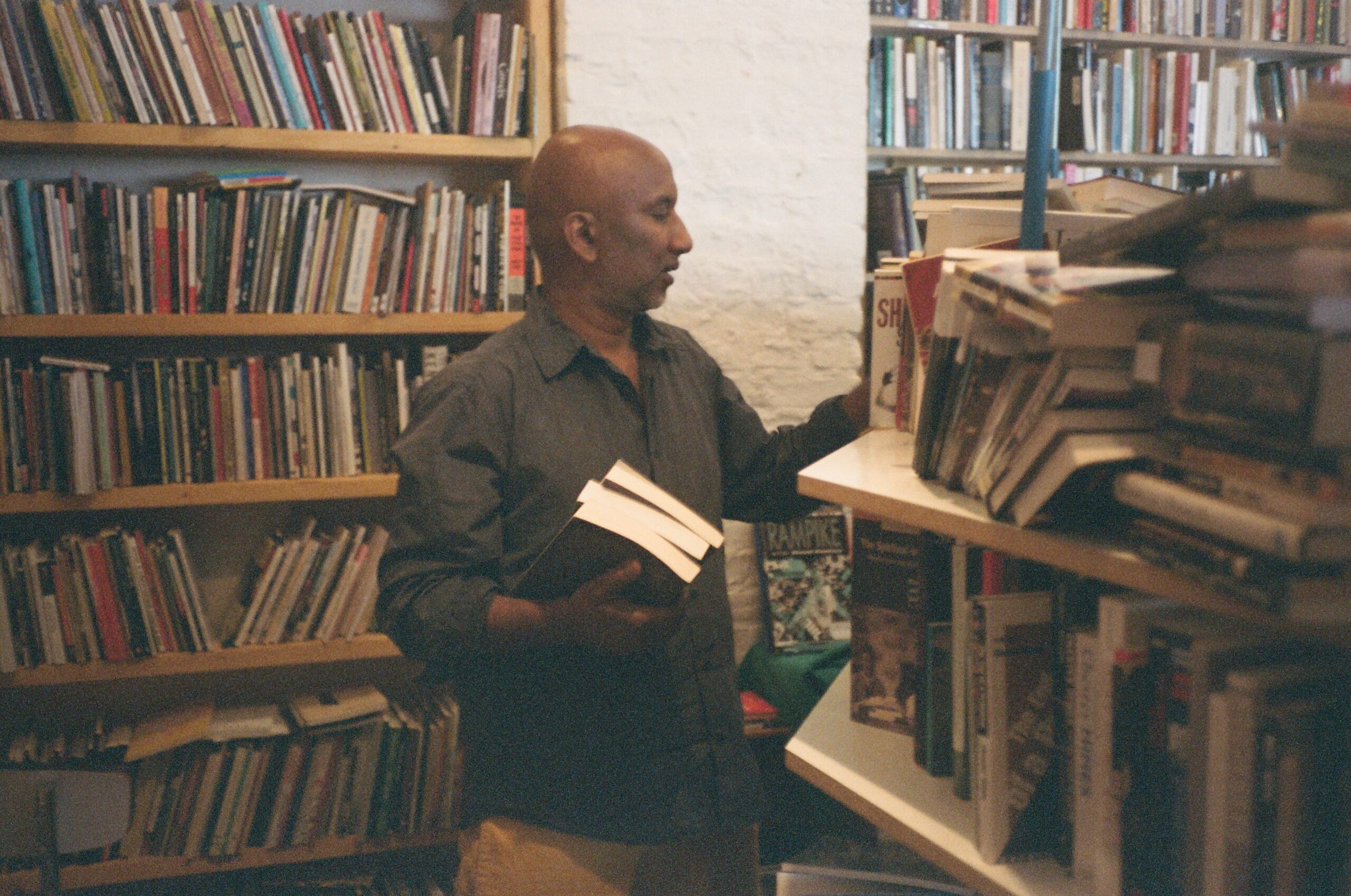

One of the Americans then asked Siddhartha for some recommendations from new European authors, and the first book he brought up was An Apartment on Uranus by Paul B. Preciado and described its explorations of gender theory. The American politely nodded, obviously disinterested in anything beyond stories of male triumph of will, so Siddhartha continued to search. I observed as he floated between his books, like a spectre whose essence derives from the millions of words collected in those perfectly maintained pages, which he gracefully references.

After the other American’s consultation was over, I wanted to try out the human search engine. I asked if he could find me tender poetry in structured form. “Of course,” he said, and he began, without much pause, to withdraw books from the shelves. An out-of-print Amiri Baraka collection. A collection by a friend he made on the street in Brooklyn. A book by his old roommate, published by Wesleyan University Press. I told him that I attended that school. “Oh yeah? Is their press still as white and tyrannical as it used to be?” I tell him that some of my smartest friends worked there during our senior year. He paused and offered an innocent, genuine smile. “Good,” he said, “maybe some things do change for the better.”

Siddhartha began to amass his collection when he found the first apartment that he stayed in for more than six months: Harlem, West 110th, 1998. “It was still rough, next to a minimum-security prison.” It was meant for inmates who were transitioning out of their sentences at larger prisons upstate or for young men serving low-level drug sentences. “I never really figured out how the two mixed,” he bemoaned.

Siddhartha was introduced to radical politics through his father, who was always keenly aware of social justice. “He was a very kind and giving person,” he remembered. And after hailing from India, which he described as a poor, unequal country with huge disparities in wealth, it was easy to identify the grander issues with the world. Once he reached college, he studied geography, a field greatly influenced by Marx, and studied American civic structures and how they sow imbalance.

But it was when Bush was re-elected in 2004 that Siddartha’s life among leftist creatives really began. He worked for the radical publisher Verso Books. He organised a library with the poet [Philip Marinomage] called “The Occupy Library” as an aid to the Occupy Movement. He found many friends in the leftist literary world, namely the esteemed poet and essayist Claudia Rankine, who had just begun teaching at Barnard. Claudia invited Siddhartha to attend her classes, and, in turn, he began taking many classes at Columbia. But the New York that Siddhartha discovered, the one that he grew in and became an important fixture of during his time in literary organising, began to disappear. “It has dissipated because people are exhausted,” he explained. “The Guliani era was bad for collectives, collectivity, socialisation, and mobilisation because he really untethered the police to any kind of a structure. It used to be disciplined and a little more cautious. I mean, the cops became quite wild, quite so much political brutality.”

He described the killing of Amadou Diallo, who was sodomised by the police, and then, of course, George Floyd. The unceasing and increasingly liberal brutality by police, paired with an ever-expensive New York, has led to an erosion of political action and a loss of committed organisers. “They’ve started families, they’ve left the city, they’ve gotten jobs, they’ve been professionalised.” After taking a moment, lost in the memories, he added, “I’m not really sure if the moment is there. Other groups have taken it on, but the pandemic has been quite brutal to a lot of collective efforts.” Ultimately, Siddhartha fell into the same wave of New Yorkers that had to leave. He wished at first to start a bookstore in New York, but gentrification won over. He left for Berlin in the Autumn of 2016, a city which had received his lush collection well.

The store itself is hidden in the corner of a courtyard surrounded by apartments occupied mainly by ageing artists who come to retire in Berlin. There is no signage advertising the store—I hadn’t noticed any mention of “Hopscotch” except that Siddhartha stamped the premiere page of every book he sold with a small graphic of a hopscotch game. If you didn’t know the store was there, it would be hard to find it at all. But people did know of the store. Covid pushed Hopscotch to up its social media presence. But otherwise, the store has gained notoriety through word of mouth and its insistence on community-building. “The summer after the pandemic last year, we did 100 fucking events in 90 days. We’ve been here and have had a permanent bad mood since then because we worked so hard.” He said with a tinge of exhaustion. “So, we built a community. We have offered the space as a place for people to have events and do whatever they want, whether it be literary, political or community-based. Plus, very importantly, we offer a range of books which are unavailable in the rest of Germany. So we get many tourists from outside of Berlin, from the rest of Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium.”

Siddhartha’s collection is grounded in books from non-Western Europe and North America or publishing houses in places with translations from cultures around the world. German publishing remains robust, but it lacks foreign translation. English remains the unifier of international literature, and his collection serves a community aching for foreign literature. Poetry from Vietnam. Post-colonial thinking from Pakistan. Revolutionary prose from South America. And Berlin’s increasingly diverse and international English-speaking population has flocked to him for literature from home, championing Siddhartha as the one-stop doctor for diasporic homesickness.

As a young literary myself, I couldn’t help but reflect on what this implied about my home. What did it mean that all the elders from the community had left New York for cheaper living elsewhere? As I spent time in Europe, two years into my tenure as a New Yorker after I and many other young people took advantage of the cheaper prices that came and went (slamming the door on their way out), I wondered if there was any hope left for the youth of New York. As outlined by J. Arthur Boyle in the blog of Siddhartha’s alma mater Verso Books, after Bernie Sanders’s hopeful presidential run was euthanised by the pandemic, followed quickly by the explosion and extinguishment of the Black Lives Matter protests, increased rent prices, and a new mayor that ran on a law and order bill, it’s looking a lot like the era that led to the organising Siddhartha was a part of without any of the actual organising.

It has instead bred a range of political engagement from total apathy to outwardly far-right extremism. But maybe New York’s literary scene survives instead in the diaspora created by gentrification, in those like Siddhartha. “I have these books because I come from New York. I can’t overstate enough,” he emphasised. “Because New York is one of the great cities where you can buy books that are cheap on the street. Not many streets in the world, cities in the world, let people sell books in the street.”

In the four weeks that I spent in Europe, I met lots of former New Yorkers, all of whom were ready to speak to me about my home, the home they left. Interestingly, more still, how many Europeans I spoke to seemed to be more aware of the New York scene than even those in it. Maybe New York survives in those who have stuck it out and those who continue to hold stock in its cultural relevance abroad.

And it survives in the ever-resolute strength of literati like Siddhartha, hosting readings for New Yorkers, pushing works by New Yorkers to hungry Europeans, and continually maintaining that old and tired and perpetually true argument that no matter where you are, it’s not as good as New York was ten years ago. And though that era may be gone, the literature produced, discussed, and collected during that time will live on in people like Siddhartha.

Words & photos by Saam Niami