I meet Silvia Rosi at Jerwood Arts after having a look around her modest but carefully curated exhibition, the outcome of the year-long Jerwood/Photoworks Award, for which Rosi was selected, alongside Theo Simpson, from more than 450 submissions. The award comes with £10,000 attached and rigorous mentoring. Rosi’s mother was a market trader in Togo, a job passed down from her own mother, and one that Rosi too would have continued if she had not grown up in Italy.

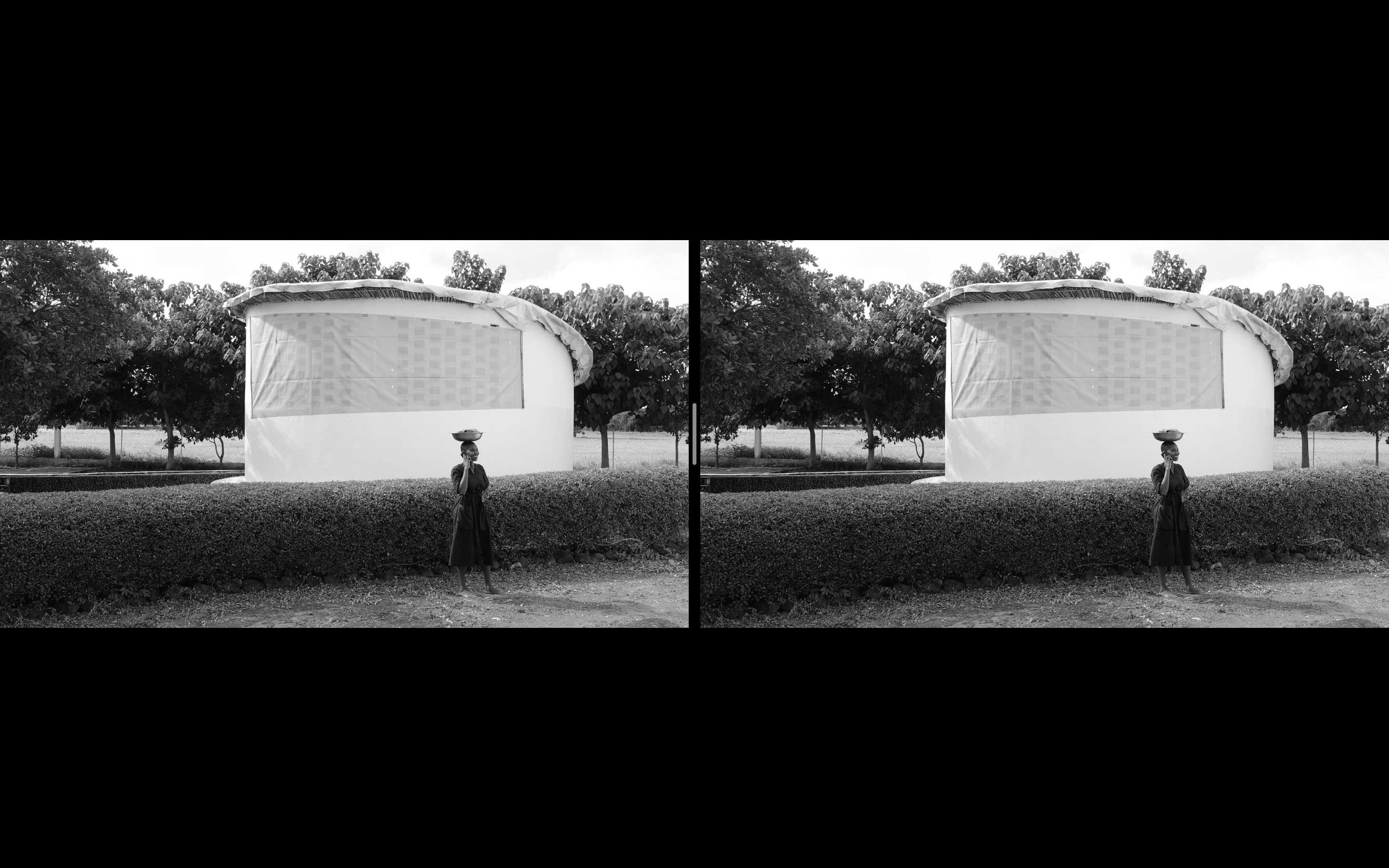

The stories unfold in fragments, through extracts conversations in texts and spoken word, short filmed scenes and staged self-portraits. “I didn’t want to force the viewer to engage with the stories, I wanted it to be more symbolic and enigmatic — so I ended up using the text in a repetitive way, as a way of using the oral histories that pass between generations, which is quite important in West Africa and Africa in general as it was the way stories were told”, Rosi explains.

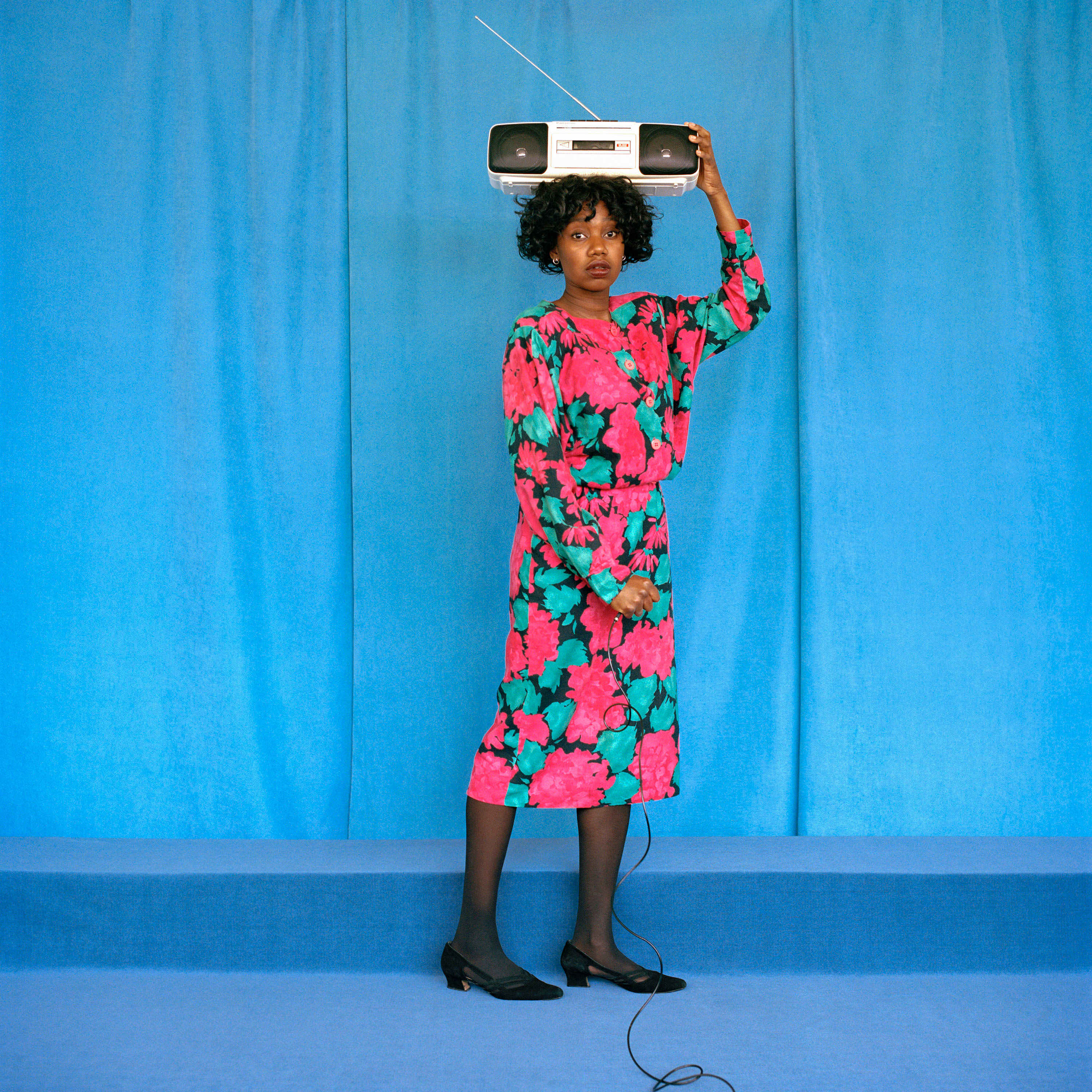

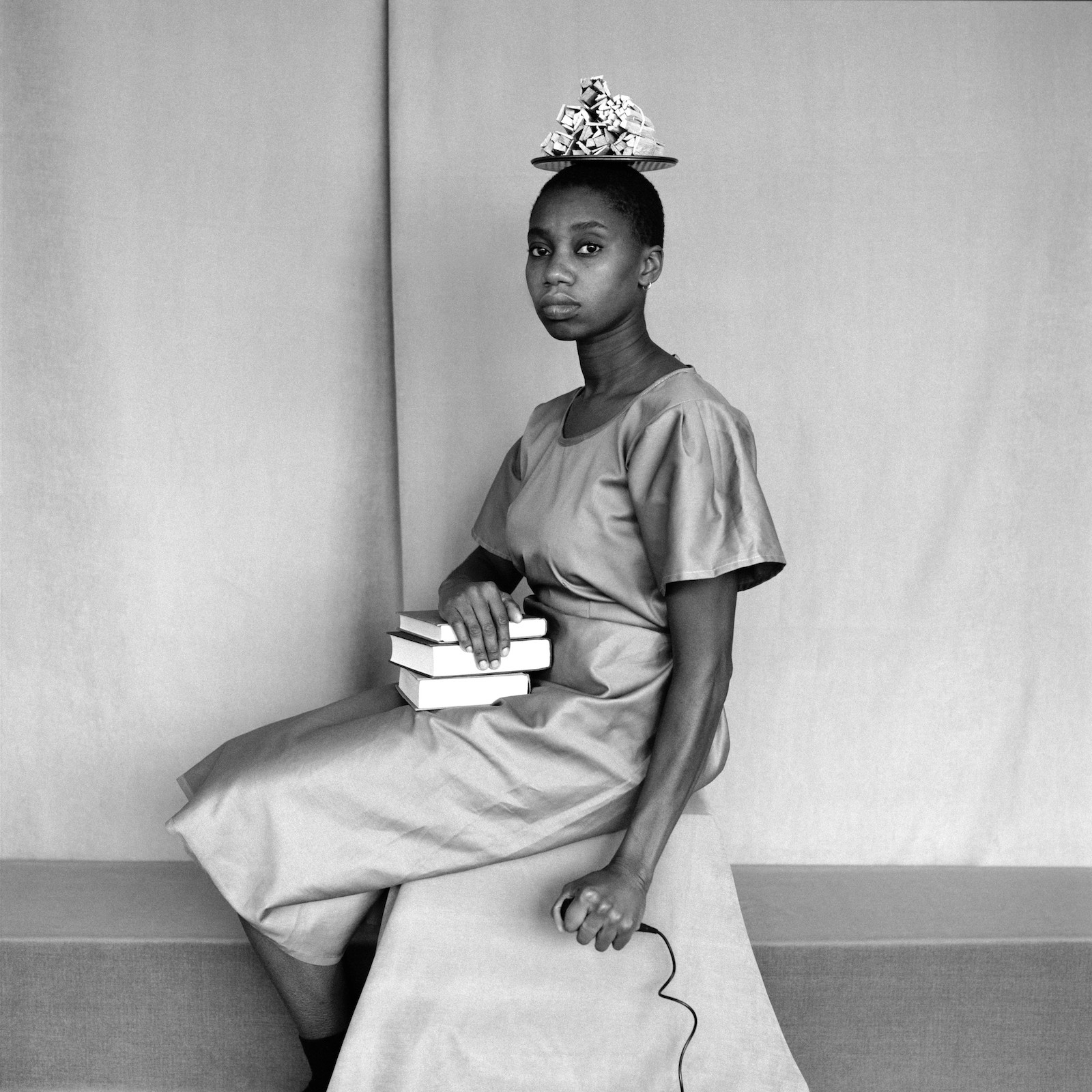

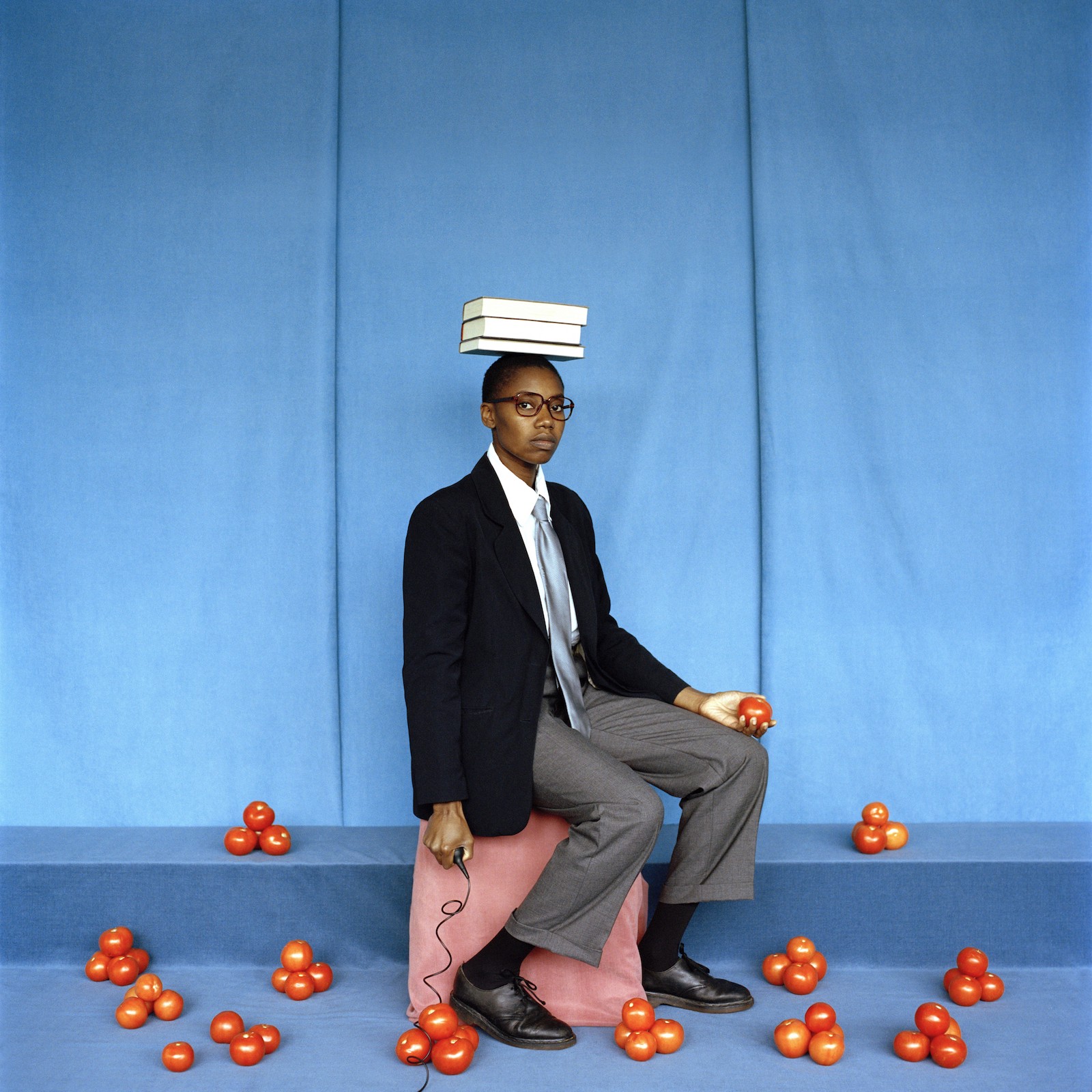

She was already experimenting with self-portraits dressed as her mother in 2016, while still a student at the London College of Communication, shot in black and white, and reminiscent of West African studio photography in their staging. It’s an aesthetic Rosi develops further here, making connections between herself, her mother and her grandmother, the transfer of female labour from one generation to the next, and matrilineal inheritance.

We’re standing here in your exhibition, which is made up of these fragments of your parent’s migration stories. How did you gather this reference material?

All the information I have comes from conversations with my mum, who usually speaks French, or a mix of French and Italian when we are speaking, but I didn’t feel confident writing them in French so I wrote them in English. They left Togo—my dad in 1988, my mum a year after—originally for France but then they heard of experiences of people being sent back to Togo from France. They’d heard that it was easier in Italy, and it kind of was the case as they didn’t have any problems there. My mum found out in 1989 about a law that allowed every migrant to have regular papers. It was really lucky! She heard it on the radio while babysitting for a lady who was a French teacher, who confirmed it was true. She’d only been in Italy two or three months at that point.

“I grew up in a small, conservative village of 4,000 people and my mum and I were the only black people”

How was your own experience growing up in Italy?

I was born in Scandiano, which is very close to Reggio Emilia up north. I hated it! I think it’s because I grew up in a small, conservative village of 4,000 people and my mum and I were the only black people. You learn how to deal with everything but it wasn’t great! Italy is more ignorant than racist — but also they don’t have a huge colonial history so it’s tricky. But obviously there’s room for improvement.

Was there any part of visual culture that you could relate to in Italy growing up as a black woman? My experience of living in Italy is that it isn’t that diverse…

My only references were my family growing up. I traveled to Togo quite a lot growing up and I’m happy my mum invested in taking us back there. The family photo album was important for me; I first started taking photographs by looking at those images and connecting to them. There’s one photograph taken of my mother a few years before she moved to Togo—she doesn’t remember who took it. It portrays my mum selling make-up at the market, which was her occupation before she moved to Italy, and that’s how she saved for the journey. It’s one of those rare pictures that wasn’t taken at the photographer’s studio because all of the other family pictures were taken there.

You reference West African studio photography in your self-portrait photographs, what kind of role did it play in your own family album in Togo?

People would go down to the studio dressed in their best clothes, usually on a Sunday after church; it was like a ritual. There’s an idea of ritual connected to photography, so if you’re not looking your best you don’t want your picture taken. For example, when I asked my grandma if I could take her picture, she started to call for everyone in the house to help her dress, and she puts on her best things and poses. It’s this amazing idea of photography as something very controlled because it’s your image, and they really believe in this power that the photographic image has.

I found lots of pictures where after, someone had died, there would be an “X” drawn over their face to free their spirit from the photograph. Photography was brought to Africa very shortly after its invention, and I was reading about this chief of a tribe who had his picture taken by a white coloniser, and he was really afraid because he felt a bit of his soul was possessed by an enemy. So there’s this idea, too, of photography that can steal the soul. That’s one of the main reasons these are all self-portraits. All of these images are inspired by the market, but you don’t see any of the market women. I didn’t want to photograph or film them.

“There’s this idea of photography that can steal the soul. That’s one of the main reasons these are all self-portraits”

You never met your dad. Has this project been a way to get to know him and understand your family better?

Yes; my mum doesn’t speak much about the past—photography has been my only way to talk about these things. If I were to just ask her it would feel odd, but if I tell her I want to create an image it feels like there’s a purpose to talk about these things. It’s strange, but it’s nice because I get to find out all of these things that I’ve, in a way, been afraid of asking. I’d ask her about her migration and how things happened, and about my dad. The self-portrait as my dad isn’t an objective representation—my dad died around eight years ago and I never knew him—but here I imagine him through my mum’s stories.