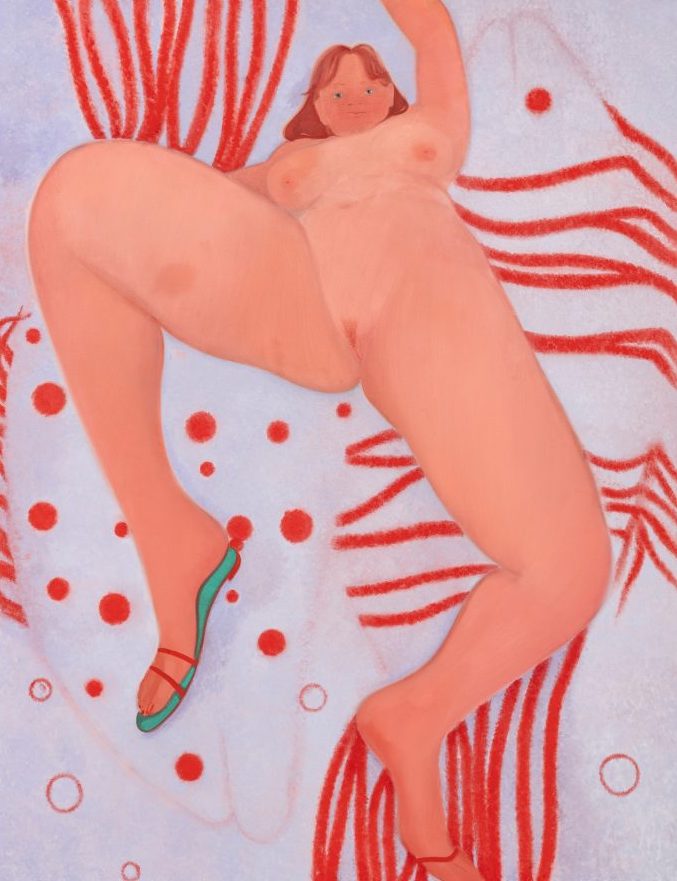

Greek artist Sofia Mitsola depicts a woman masturbating at the water’s edge in Siren (2018). Her legs are splayed and her posture is relaxed. She stares straight at you with an air of casual indifference. Submerged, the edges of her right foot begin to blur, hinting at transformation.

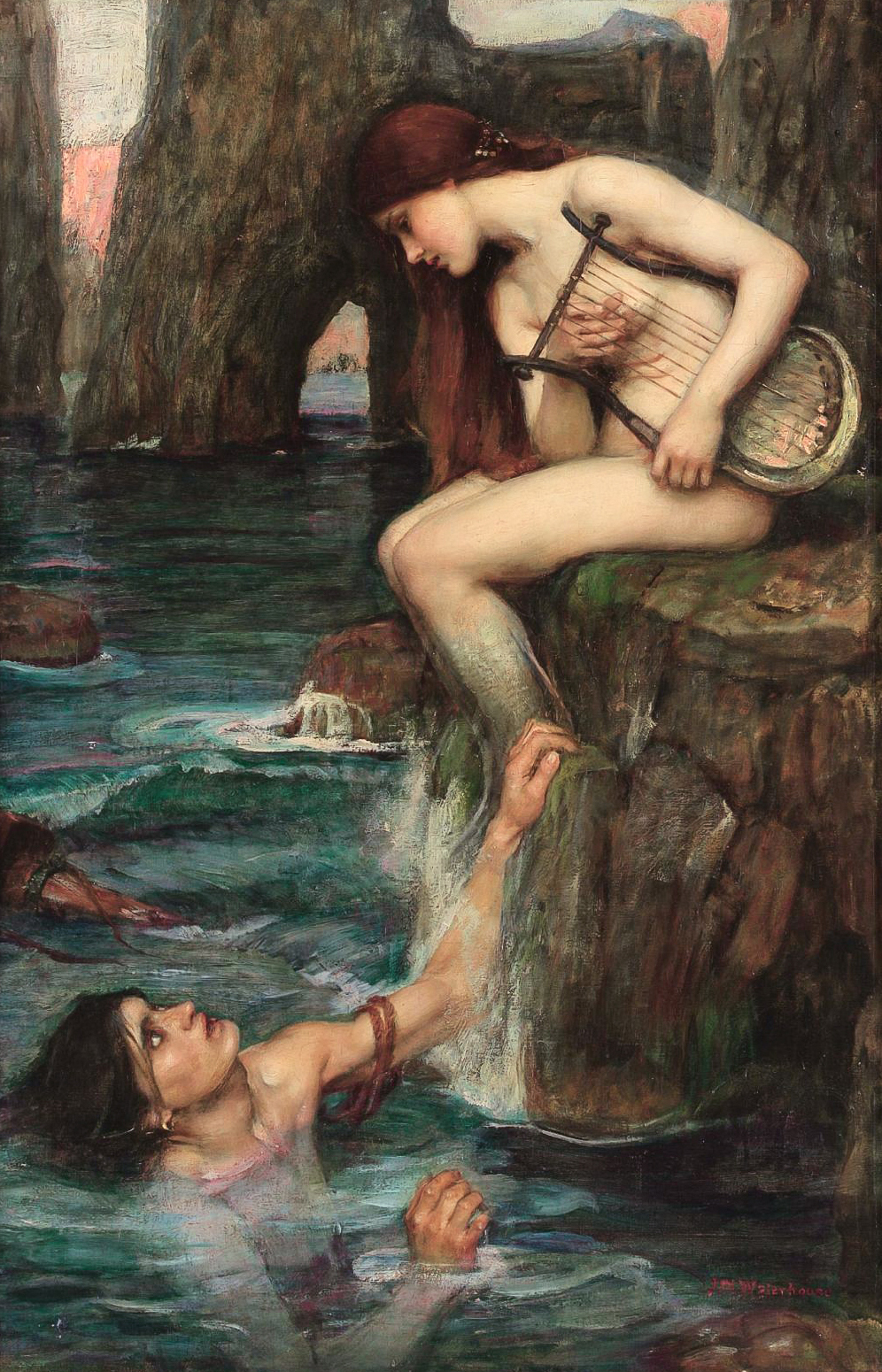

The water’s edge is also the point of metamorphosis in John William Waterhouse’s The Siren (1900). With the indulgent intensity and ethereality of the Pre-Raphaelite style, he paints a naked girl with flowing auburn hair playing the lyre on a rock. Her eyes are locked on the shipwrecked sailor in the waves below, who gazes up at her in fear and fascination. Her lower legs flow into shimmering fish scales, calling up another of Waterhouse’s paintings that year, A Mermaid.

While Waterhouse revels in the murky misogynistic trope of the siren as the original femme fatale, luring sailors to their deaths, Mitsola harnesses this narrative of seduction to explore themes of power, pleasure and predation. Both artists take their cues from classical imagery, and contribute to a visual mythos of oceanic depths.

Washed together in our cultural consciousness, sirens and mermaids have haunted the seashores of imagination for thousands of years, compelling artists and storytellers with a maelstrom of associations spanning desire, danger, possibility, hope and renewal.

“Anywhere and anywhen humans have lived by water, we’ve created mermaids,” says historian Vaughn Scribner, whose book Merpeople: A Human History traces the cultural ubiquity of water spirits from the Assyrian fertility goddess Atargatis to the ningyo of Japan, from Mami Wata in Africa to the Russian rusalka.

“Our creations of merpeople are at once fantastical, but they’re also very intimate,” says Scribner. He highlights the differences between sirens and mermaids in early mythology and points to Odysseus’ fateful encounter with the sirens, a scene reimagined by Waterhouse in his narrative painting Ulysses and the Sirens

(1891).

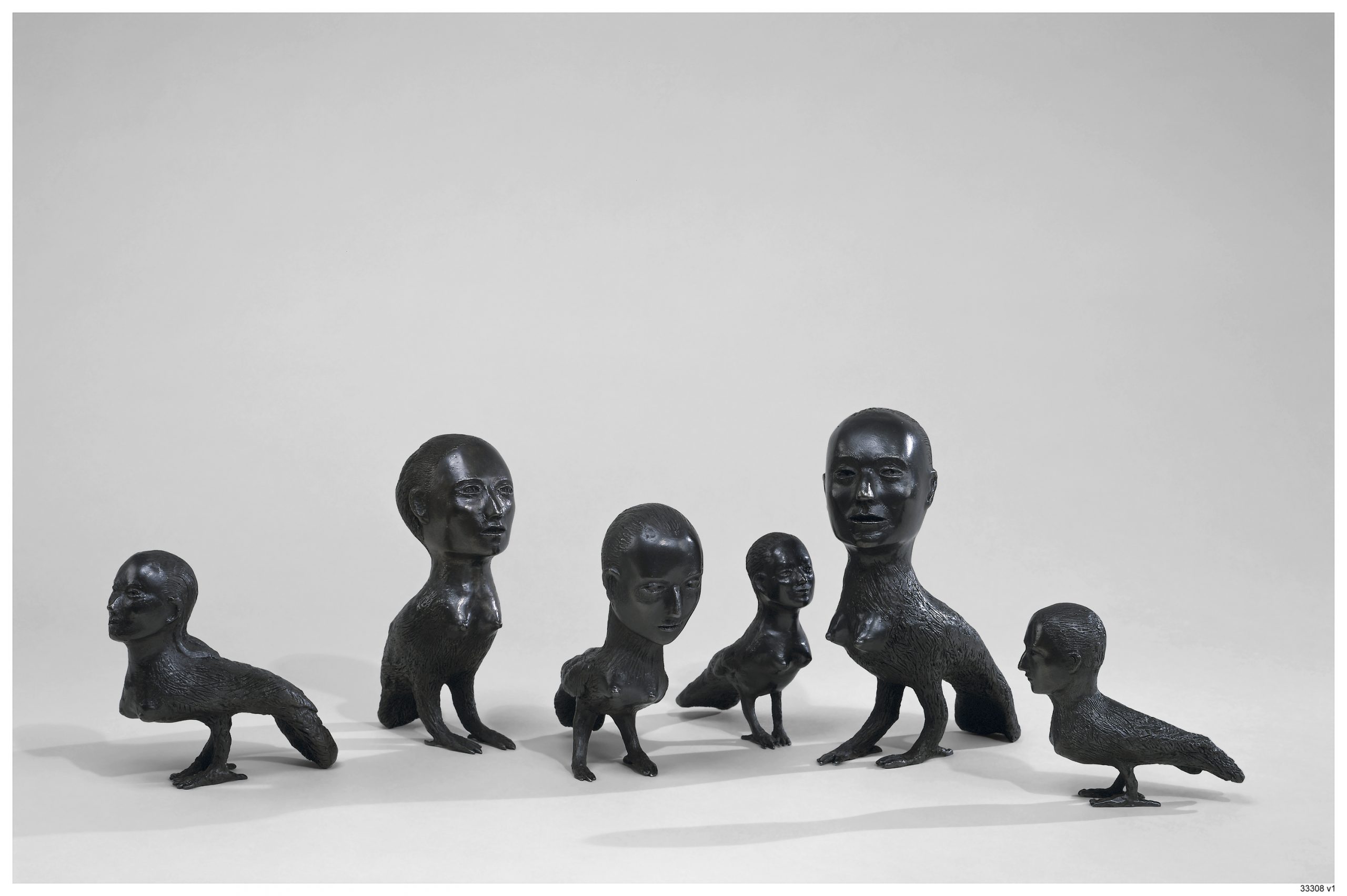

In Homer’s epic, they are not the sexy fish-women of today, but hideous hybrids: half-woman, half-bird. Known for her reclamation of ancient tales, German-American artist Kiki Smith reworked this monstrous imagery of womanhood and disfigurement into her bronze sculptures of Sirens and Harpies in 2002.

“Washed together in our cultural consciousness, sirens and mermaids have haunted the seashores of imagination for thousands of years”

In scrutinising medieval bestiaries and crude carvings in cathedral architecture, Scribner holds the Christian Church responsible for pasting the destructive characteristics of sirens onto the template of the mermaid and creating “the ultimate representation of the dangers of lust and sexuality”. Just as medieval cartographers used mermaids as code for turbulent waters, feminine beauty could cause men to lose their way.

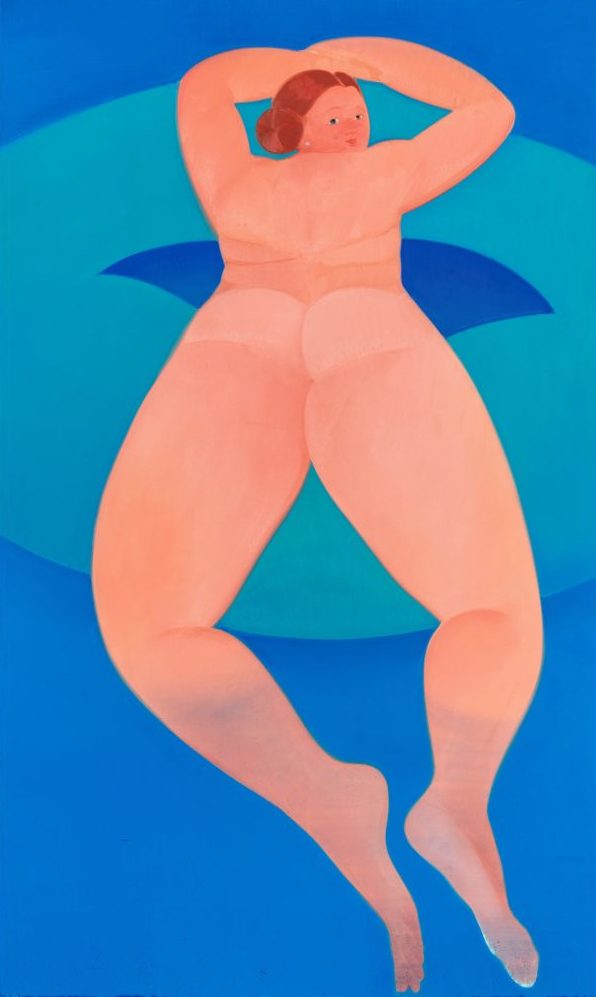

Mitsola channels this power dynamic into her work. Mixing translucencies and bright, flat colours, she portrays the nude female body within the underwater world. Her figures are soft and voluminous, though their eyes are sharp and almost always fixed on the viewer.

“I want viewers to prey upon my figures, to take pleasure in their naked bodies: while they’re doing that, they become vulnerable,” she says, recalling the predatory myth of the siren. “If there is a confrontation between the viewer and the painting, the painting always wins. The viewer withdraws, but the painting never stops looking.”

Poised at the border between sea and land, sirens and mermaids are also a recurring emblem of forbidden or unrequited love. In probing this, queer historian and folklorist Sacha Coward has uncovered a wealth of queer history surrounding the most famous piece of mermaid literature, Hans Christian Anderson’s The Little Mermaid (1837). Anderson, who some biographers believe to have been biromantic, was rejected by his beloved friend Edvard Collin and created this fairytale after Collin decided to get married.

“Anderson writes a story about a creature that cuts off her own tongue so that she can be with the man of her dreams, and then doesn’t get that man,” says Coward. “She lets him marry someone else and sacrifices herself by turning into sea foam. It’s heartbreaking, and this is not a coincidence. It’s written by a man who’s just lost the love of his life (one of many, admittedly) and cannot talk about that loss. I think The Little Mermaid is the saddest queer love letter never sent.”

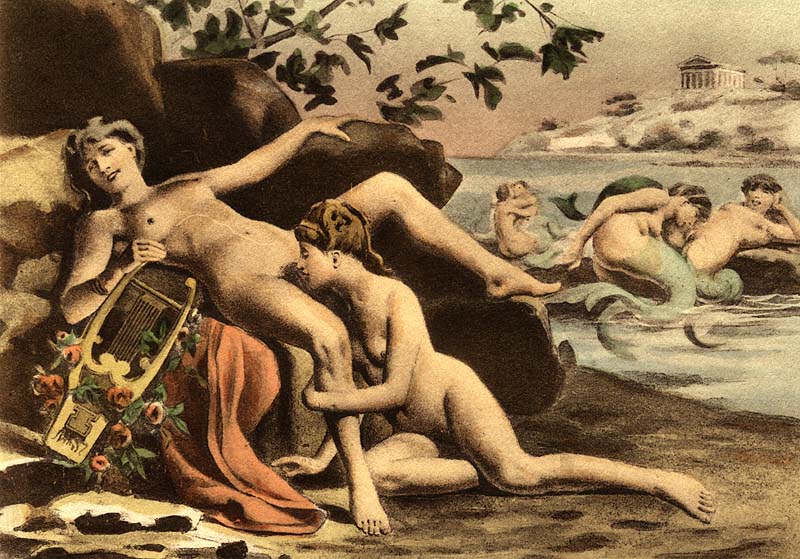

Evelyn de Morgan, The Sea Maidens, 1885-6

Painted in response to Anderson’s fairytale, queerness also ripples around Evelyn de Morgan’s The Sea Maidens (1885-6). The Pre-Raphaelite modelled all five mermaids on her maid and possible love interest Jane Hales, whose face is rendered again and again in sensuous detail like the intricate brush strokes on the mermaids’ scales. The figures embrace one another in what was a rare expression of the nude female form as seen through the eyes of a woman.

“Written by a man who’s just lost the love of his life, The Little Mermaid is the saddest queer love letter never sent”

Coward believes that Anderson’s story contributed towards a cultural shift in depictions of mermaids from evil temptresses that lure humans to their deaths to compassionate, love-lost beings threatened by those on land. Mexican artist Ana Leovy exhibits this shift in her painting, The mermaid cried a sea of tears so that he could sail away (2020), with the ‘sea of tears’ a selfless act of rescuing or the catharsis of heartbreak. It disrupts the earlier trope of fatal attraction epitomised in Edward Burne-Jones’s The Depths of the Sea (1887) in which a mermaid drags the dead body of a naked man down to the glinting sea bed, a small smile on her face.

Adopted as an empowering icon of gender diversity by gender variant and transgender youth support network Mermaids UK, the queer mythology surrounding these creatures also pertains to their fluidity. “It’s this metaphor of transforming your body, but also the fact that most merfolk don’t have visible genitalia, their gender identity is not about what goes on beneath the waist,” says Coward.

“Our creations of merpeople are at once fantastical, but they’re also very intimate”

However, he admits that for cis hetero male painters of the Romantic era, the tail could have been all the more provocative because “that which is covered invites speculation”. He notes fin-de-siècle artist Édouard-Henri Avril’s erotic illustrations of Sappho having sex with her lover, with mermaids engaging in cunnilingus in the background.

Perhaps the most fluid mythical mermaid is Mami Wata, the water spirit and serpent tamer venerated throughout much of Africa and the African Atlantic. “We associate Mami Wata as a female-bodied person, and we also associate her as being half-human, half-fish,” explains writer Marcelle Mateki Akita for the BBC’s The Forum. “There are also male-bodied versions of Mami Wata, termed Papi Wata. When we think about the many depictions of this deity, there is a shapeshifter element, which I find really fascinating when thinking about gender and race.”

Mami Wata’s significance as the protector of the water kingdom stretches far across the African diaspora. “Water symbolises life, but it also symbolises departure and return,” explains Mateki, in reference to the transatlantic slave trade. “Mami Wata connects people of African descent back to the continent itself. She’s seen as a symbol of sorrow and of hope.”

Mami Wata is an enduring example of how these magical creatures contain multitudes. Mermaids possess a symbolism as diverse and as mutable as the ocean itself. They are continually being reshaped.

Madeleine Pollard is a Berlin-based journalist specialising in culture and current affairs